http://www.metamute.org/editorial/artic ... a-federiciPERMANENT REPRODUCTIVE CRISIS: AN INTERVIEW WITH SILVIA FEDERICI

By Marina Vishmidt, 7 March 2013

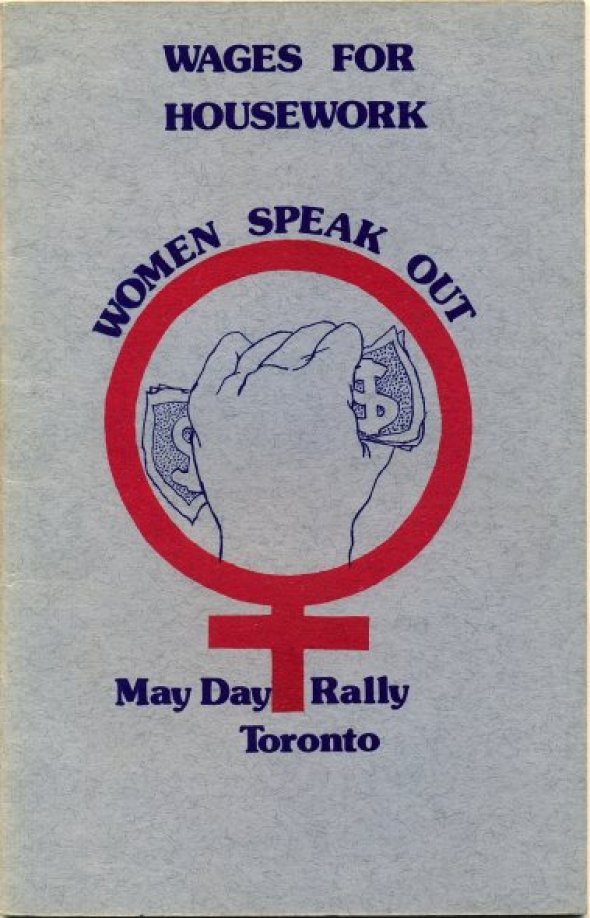

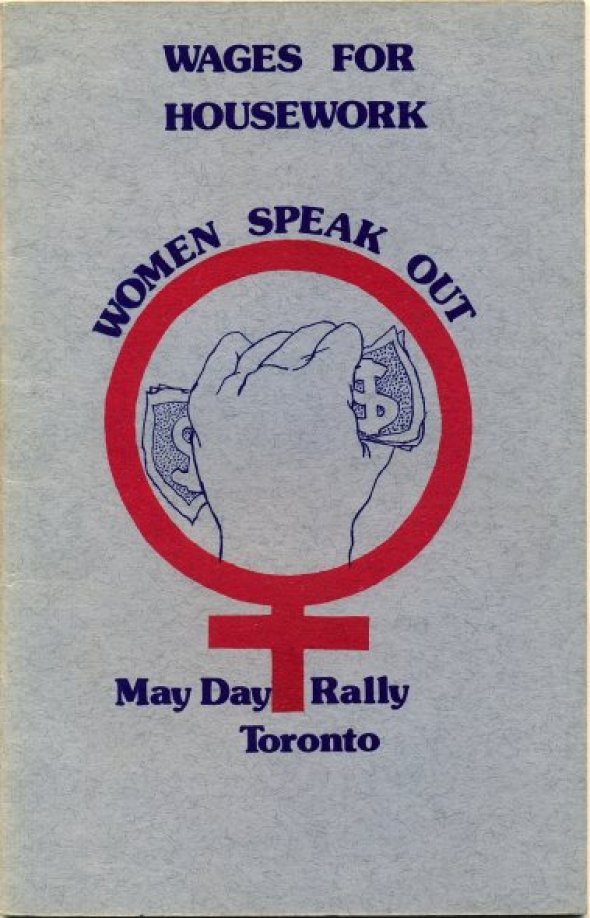

On the occasion of the publication of an anthology of her writing and the accession of a Wages for Housework NY archive at Mayday Rooms in London, Marina Vishmidt interviewed Silvia Federici on her extensive contribution to feminist thought and recent work on debt activism (with contributions by Mute, Mayday Rooms and George Caffentzis)

On the occasion of the publication of an anthology of her writing and the accession of a Wages for Housework NY archive at Mayday Rooms in London, Marina Vishmidt interviewed Silvia Federici on her extensive contribution to feminist thought and recent work on debt activism (with contributions by Mute, Mayday Rooms and George Caffentzis)Mute: In the text ‘Wages Against Housework’ (1975) you refer to the problem of women’s work (even waged) as the impossibility of seeing where ‘work begins and ends’. Just as French group Théorie Communiste argue that ‘we’ are nothing outside of the wage, you also speak of the problem of unwaged women as being outside of a ‘social contract’. How does this reflect the capital-labour relation today? How much has this situation, then specific to women and some other workers, generalised? How are we to act from the perspective of this being ‘nothing’? Is it still a question of self-identification or dis-identification?

Silvia Federici: We should not assume that those who are unwaged, who work outside the social contract stipulated by the wage, are ‘nothing’ or are acting and organising out of a position of no social power. I would not even say that they are outside the wage relation which I see as something broader than the wage itself. One of the achievements of the International Wages For Housework Campaign, that we launched in the 1970s, was precisely to unmask not only the amount of work that unwaged houseworkers do for capital but, with that, the social power that this work potentially confers on them, as domestic work reproduces the worker and consequently it is the pillar of every other form of work. We saw an example of this power – the power of refusal – in October 1975, when women in Iceland went on strike and everything in Reykjavik and other parts of the country where the strike took place came to a halt.

Undoubtedly wagelessness has expanded worldwide and we could say that it has been institutionalised with the ‘precarisation of work.’ But we should resist the assumption that work conditions have become more uniform and the particular relation that women as houseworkers have to capital has been generalised or that work in general has become ‘feminised’ because of the precarisation of labour. It is still women who do most of the unpaid labour in the home and this has never been precarious. On the contrary, it is always there, holidays included. Access to the wage has not relieved women from unpaid labour nor has it changed the conditions of the ‘workplace’ to enable us to care for our families and enable men to share the housework. Those who are employed today work more than ever. So instead of the feminisation of waged work we could speak of the ‘masculinisation’ of ‘women’s labour,’ as employment has forced us to adapt to an organisation of work that is still premised on the assumption that workers are men and they have wives at home taking care of the housework.

If I understand it correctly, the question of ‘dis-identification’ revolves around the assumption that naming your oppression and/or identifying your struggle as that of a particular type of worker confirms your exploitation. In other words, a struggle waged by a slave, or a wage worker or a housewife could never be an n emancipatory struggle. But I do not agree with this position. Naming your oppression is the first step towards transcending it. For us saying ‘we are all housewives’ never meant to embrace this work, it was a way of denouncing this situation and making visible a common terrain on the basis of which we could organise a struggle. Recognising the specific ways in which we are exploited is essential to organising against it. You cannot organise from a position of ‘nothingness.’ ‘Nothingness’ is not a terrain of aggregation. It does not place you in a context, in a history of struggles. To struggle from a particular work-relation is to recognise our power to refuse it.

I also find it problematic to refer to specific forms of work and exploitation as ‘identities’ – a term that evokes unchanging, essentialising characteristics. But there is nothing fixed or ‘identifying’ in the particular forms of work we perform, unless we decide to dissolve ourselves in them, with what Jean-Paul Sartre would call an act of ‘bad faith’. Whatever the form of my exploitation this is not my identity, unless I embrace it, unless I make it the essence of who I am and pretend I cannot change it. But my relation to it can be transformed by my struggle. Our struggle transforms us and liberates us from the subjectivities and social ‘identities’ produced by the organisation of work. The key question is whether our struggles presume the continuation of the social relations in which our exploitation is inscribed, or aims to put an end to them.

For the same reason I am sceptical about calls to ‘abolish gender’.

All over the world women are exploited not only as generic workers or debtors, but as persons of a specific gender, for example through the regulation of our reproductive capacity, a condition that is unique to women. In the United States poor, black women are at risk of being arrested just for the fact of being pregnant, according to a health report issued in the US in January. In Italy single mothers who turn to the social services for some help risk having their children taken away from them and given up for adoption. Again, women in jail receive very different treatment to men. And we could multiply the examples. How do we fight against these ‘differences’ without using categories such as gender and race? From the call centres to the prisons gender and race matter, the bosses know it, the guards know it, and they act accordingly; for us to ignore them, to make them invisible is to make it impossible to respond, because in order to struggle against it we have to identify the mechanisms by which we are oppressed. What we must oppose is being forced to exist within the binary scheme of masculine and feminine and the codification of gender specific forms of behaviour. If this is what ‘abolishing gender’ means then I am all for it. But it is absurd to assume that any form of gender specification must always, necessarily become a means of exploitation and we must live in a genderless world. The fact that gender historically, in every society based on the exploitation of labour, has been turned into a work function and a mark of social value does not compel us to assume that gender will necessarily, always be a means of exploitation and we have to pretend that there is no difference between women and men or that every difference will be abused. Even in my own lifetime, what ‘woman’ means has changed immensely. What being a woman meant for my mother is very different to what it means for me. In my own life, for example, I have reconciled myself to being a woman because I've been involved in the process of transforming what being a woman means. So the idea that somehow gender identities are frozen, immutable, is unjustified. All the philosophical movements of the 20th century have challenged this assumption. The very moment you acknowledge that they are social constructs you also recognise that they can be reconstructed. It will not do to simply ignore them, push them aside and pretend we are ‘nothing’. We liberate ourselves by acknowledging our enslavement because in that recognition are the reasons for our struggle and for uniting and organising with other people.

Image: Silvia Federici in London, November 2012

Image: Silvia Federici in London, November 2012 M: The other side of the same question: how would you characterise the ongoing division of labour today, particularly the conflict between work covered by the wage and that outside of it? How does this still structure the distribution of roles? Arguably, for some time, ‘wages’ have been paid to women (particularly women with families in the UK – tax credits, child benefit etc.) yet these social ‘wages’ still reproduce division within the class. How have these measures recomposed class and class division?

SF: Generally speaking I’d say that the social division of labour internationally is still structured by the sexual division of labour and the division between waged and unwaged work. Reproductive work is still mostly done by women and most of it, according to all statistics, is still unpaid. This is particularly true of childcare, which is the largest sector of work on earth, especially in the case of small children, aged one to five.

This is something now broadly recognised, as most women live in a state of constant crisis, going from work at home to work on the job without any time of their own and with domestic work expanding because of the constant cuts in social services. This is partly because the feminist movement has fought to ensure that women would have access to male dominated forms of employment, but has since abandoned reproductive work as a terrain of struggle. There was a time, in the US at least, when feminists were even afraid to fight for maternity leave, convinced that if we asked for ‘privileges’ we would not be justified in demanding equal treatment. As a result, as I mentioned already, the ‘workplace’ has not changed, most jobs do not have childcare and do not provide paid maternity leave. This is one struggle feminists today should take on.

I don’t think that ‘wages’ are being paid to women for the domestic work they do. Tax credits and family allowances are not wages. They are bonuses to those who are employed and in most countries they are paid to the family, which most often means to men. They do not remunerate reproductive work, which is why they reproduce the divisions within the class.

Marina Vishmidt: I suppose child benefits are paid regardless of employment, so that would be a second form of benefit?

SF: I don’t know about England. In the US, until the 1990s, there was a federal program called Aid To Families with Dependent Children that allocated some monies to sole mothers. It was not sufficient, but it was important because it gave women some autonomy, the ability to leave a man if they wanted to, and the recognition that raising children is work. We used to say that ‘Welfare is the first wages for housework.’ However, since the mid 1990s, AFDC has been practically eliminated. We are told that Welfare has been replaced by Workfare because now after two years women are forced off the rolls, even though many cannot find employment. Also, what women receive has been reduced. This has been a defeat, because many women now live in miserable conditions, in fact the image of the poor is that of a state-supported single mother. Because it was a public declaration that reproductive work is not work, it hid how much employers and the state exploit this work. In the US we still have to fight even to have paid domestic workers recognised as workers. So far only New York State has taken this step, partially adopting in 2010 a Bill of Rights that domestic workers had fought for years. But then, recently, Governor Brown in California turned down a similar Bill.

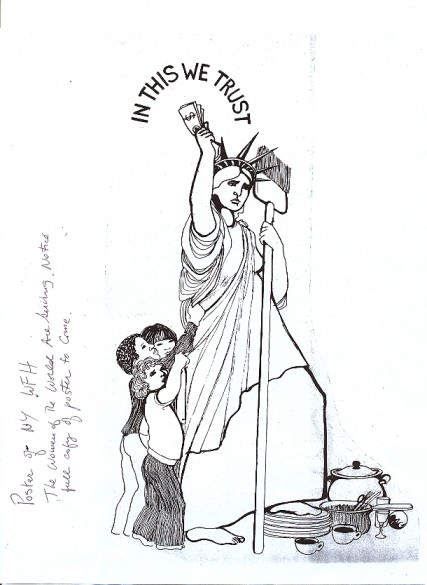

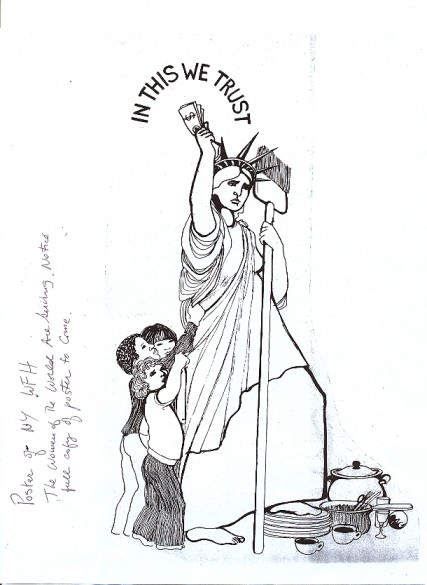

Image: MayDay Rooms website, Women of The World are Serving Notice, poster Federici Collection Wages for Housework NY preliminary design, Date unknown. Forces of (Re)production

Image: MayDay Rooms website, Women of The World are Serving Notice, poster Federici Collection Wages for Housework NY preliminary design, Date unknown. Forces of (Re)production M: In an interview for LaborNet TV [http://linkme2.net/tf] you respond to a question about your disagreement with the Marxist position on capitalism as a precursor to communism. You argue that the development of the forces of production is predicated upon the sexual division of labour and thus the notion that a communist project can simply seize the forces of production and repurpose them for the ends of egalitarian form of society is misconceived. Certainly, many forms of technology would have little application without a profit motive, but how, without technology, would new social relations breaking with capitalist domination avoid the re-imposition of work, either through ‘return to nature’ to primitivist conditions – i.e. work as the entire future horizon of humanity – or as in utopian communitarian co-operatives where work is ‘fairly’ re-distributed under communal pressure?

SF: I am not against technology. Technology is an indispensable part of our lives and it existed long before the advent of capitalism. In fact, Karl Marx underestimated the technological achievements of pre-capitalist societies. Think of the technology of food production. The populations of Mesoamerica invented most of the foodstuffs that we eat today. They invented the tomato, 200 types of corn and potatoes. Marx credits capitalism too much for having unleashed the productive power of human labour. But my criticism of Marx concerns, above all, his belief that large scale industry is a necessary precondition for the advent of communism and generally for human development. In reality, much of the technology that capitalism has developed was aimed at destroying workers’ organisations and reducing the cost of labour production, so it cannot be taken over and redirected to positive goals. How do you take over a nuclear or chemical plant for instance? Marx himself recognised (in Capital Vol. 1) that the industrialisation of agriculture ‘depletes the soil as it depletes the worker,’ although he also upheld it as a model of rational exploitation of our natural resources. Most capitalist technology is destructive of the environment and our health. We see clearly today that industry is eating up the earth, and if we had a communist society much of the work we would have to do would be spent just cleaning up the planet. This means we have to rethink every type of technology. Take the computer, for instance, just one computer requires tons of soil and pure water. So the idea that we can have a world in which machines do all the work and we can just be their supervisors, Marx’s vision in the Grundrisse, is untenable. First we have to work to build the machines. They are not self-reproducing. Somebody has to take the minerals out of the ground and build them. They also require a particular form of social organisation and social control that is the opposite of the type of co-operation that people need for the construction of an egalitarian society.

Another important issue is that large scale industrialisation cannot reduce socially necessary labour, since a large part of the work on this planet – the work of reproducing human beings – is work that is very labour intensive, in which emotional, physical and intellectual labour are inseparably combined, and cannot be industrialised except at a tremendous cost for those we care for. Think, for example, of the work of caring for children or for those who are sick and not self-sufficient. I know that in Japan and the US they are inventing household robots and even robots that care for people like nursebots. But is this the society we want?

MV: But as we were discussing last time, the question of technology is also very contradictory in different parts of Marx’s work.

SF: Yes, in different parts of his work Marx recognised the destructive impact of industrialisation, on agriculture, for instance. But he obviously assumed that the technology capitalism has developed could be restructured and re-channelled towards different goals. He idealised science and technology. He assumed they could be appropriated by workers and transformed in a way that would enable us to liberate ourselves from much work that we do out of necessity, not because it enhances our capacities and powers.

The Refusal of WorkMV: I guess if ‘refusal of work’ were thought of as the refusal of particular social relations then, as Mariarosa Dalla Costa writes, we would not want the industrialisation and collectivisation of food service because there would still be women working in those kitchens. But we can also think of collectivised laundries as social spaces in Soviet and social democratic states, for example. So we see how certain types of reproductive work can be industrialised, but it's the social relations of that work that matter.

SF: Certainly. When we speak of ‘refusal of work’ we have to be careful. We need to see that the work of reproducing human beings is a peculiar type of work, and it has a double character. It reproduce us for capital, for the labour market, as labour power, but it also reproduces our lives and potentially it reproduces our revolt against being reduced to labour power. In fact, reproductive labour is important for the continuation of working class struggle and, of course, for our capacity to reproduce ourselves. This is why we need to understand the double character of this work, so that we refuse that part of the work that reproduces us for capital; whereas we cannot refuse this work as a whole, because labour-power lives in the individual, and if we refuse it completely we risk destroying ourselves and the people we care for. I think that one of the most important discoveries the women’s movement made was that we could refuse some of this work without jeopardising the well being of our families and communities. Recognising that this work is not just a service to our families, but it is also a service to capital liberated us from the sense of guilt we always experienced whenever we wanted to refuse it. It was important for us to realise that this work does not simply reproduce children, partners, communities, but reproduces us as present or future workers because in this way we could think of a struggle against housework as a struggle against capital rather than against our families. We began to disentangle those aspects of domestic work that reproduced us from those that reproduced capital. So the issue is not so much the ‘refusal’ of reproductive work, but its reorganisation in a way that makes it creative work. This, however, can only happen once this work is not aimed at providing workers for the labour market, when it is not subsumed to the logic of capital accumulation, and we control the means of our reproduction.

The Tyrannies of MicrofinanceMV: I think I'd also like to come back to your talk on microfinance with regard to this. What you said, that was so important, was how community bonds are actually used by microfinance banks to hyper-exploit the recipients of the loans. I guess that’s what I had in mind, how these forms of non-capitalist or pre-capitalist communal bonds are actually de-composed by capital and how that can be resisted. Witch-hunts would be another aspect of this.

SF: The World Bank and other financial institutions have realised that social relations are crucial, they see them as a ‘social capital’ and they used them, manipulate them, co-opt them to neutralise their subversive potential and domesticate the commons. The World Bank, for instance, uses the idea of protecting the ‘global commons’, presumably preserving them for the well being of humanity, to privatise forests. They expel the populations – fishermen, indigenous people – who lived in them. In the ’90s, in Africa, the Bank also set up communal groups, artificially created, often made up of local authorities, that had the power to alienate land. This allowed them to get around the fact that people resisted the dismantling of communal land ownership and introduction of individual land titling.

In the case of microfinance, banks and other financial agencies are turning the support groups that women have organised into self-policing groups. I’ve read that in Bangladesh, when one of the women in the group does not pay back the loan she has taken, the others put a lot of pressure on her and even attack her physically to force her to pay. The banks’ or the NGOs’ officers and the other women in the group ‘break her house’ and take away her pots, which is a great humiliation for a woman.

This is more than an attack on people's means of reproduction. It is an attack on the bonds that people have created on the basis of shared resources. This attack on communal solidarity, on the forms of co-operation people have created to strengthen their capacity for resistance, is probably the most destructive aspect of microfinance.

We need to understand the historical conditions that make it possible for these groups to be destroyed. Generally the areas in which microfinance has taken root are areas where the population has been weakened by years of authoritarian rule, or by austerity programs, or by natural disasters or all of the above, as in the case of Haiti after Hurricane Sandy, which prompted the intervention of the World Bank with a two million dollar investment in micro-loans. There is also the ideological work of the religious sects, fundamentalists of one type or another. Not all communal forms have the same capacity to resist the assault made on them through various forms of privatisation and dispossession.

This is something that has to been taken into account in the discussions of the commons. We need to examine what is happening to the existing commons. In parts of Latin America, new commons have been created, as in the case of the Zapatistas or the MST. Also, in response to structural adjustment, women have set up communal kitchens, communal cooking, communal shopping. In other parts of the world, like Africa and India, communal lands have become battlefields. In parts of Africa, as the land is shrinking because of massive land-grabbing and giveaways by governments to companies (mining, agro-fuels, agribusiness), the male commoners are pushing women out of the commons. They are introducing new rules and regulations concerning who ‘belongs’ and who doesn’t. They may expel a wife from the usufruct of land, saying she belong to a different clan. It is important to see in what context commons can be turned against themselves.

The story of microfinance demonstrates how pernicious the idea that salvation comes through money borrowing is. Reports from many parts of the world, e.g. Bangladesh, Bolivia, Egypt, show that most women who took micro-loans are worse off than they were at the time they took them. Their support group may not be there any longer, they are far more in debt than before, so that they have to go to moneylenders to pay back the debt. Often they have to keep their children at home (working?) to help them pay the debt. So the World Bank’s argument that money is the creative power of society and borrowing some will pull you out of poverty has to be rejected. Some women do profit from the micro-loans, but they are usually those who co-operate with the managers in the policing and supervising work.

Financialisation and the Wages of DebtMV: I’d like to follow-up on that with something else you said on Monday evening which was that financialisation shows a shift in capital’s investment in the working class, insofar as once there was an idea of long-term investment and a kind of social wage and welfare state institutions, and now there is a kind of foreshortening of that investment, so the financialisation of reproduction means extracting value in every moment.1

SF: Yes, every aspect of reproduction is becoming an immediate a site of accumulation. This is because you now have to pay for many services that in the past were provided by the state. In the post-WWII period, the capitalist politics was to invest in the reproduction of the workforce that was seen as a sort of ‘human capital’ to be developed. This is what is usually referred to as the ‘welfare state’. Behind it there was the idea that investing in workers’ health, education, housing, would pay out in terms of increased workers' productivity and discipline. But clearly the struggles of the ’60s convinced the capitalist class that having more space and time would not make workers more productive but only more rebellious. This is why we have seen an inversion. Now we have to pay for our reproduction, they tell us it is our responsibility. It is a major change. First of all it is a change in the temporal structure of accumulation. Employers now don’t invest in the long term, in our future productivity. They do not expect us to become more productive in the future. They want to accumulate immediately from our ‘investment’ in our education, from the interest on our credit cards: they want to cash in immediately. So, reproduction becomes immediately a point of accumulation. That’s a very important change. This has also changed the relation between workers and capital. Being indebted to a bank hides the fact that there is a relation of exploitation. As a debtor, you don’t appear any longer as a worker. Debt is very mystifying. It brings about a change in the management of class relations. This is what is at stake in the ideology of ‘self-investment’ and ‘micro-entrepreneurship’, which pretends that we are sole beneficiaries of our education and our reproduction, and occludes that the employers, the capitalist class, benefits from our work. Debt also has a disaggregating effect; it isolates us from other debtors, because we confront the banks as individuals. So, debt individualises, it fragments the class relation, in a way that the wage did not. The wage in a sense was a sort of common. It recognised not only the existence of a work relation but of a collective relation strengthened by a history of struggle. Debt dismantles both. We see it with the struggle of students indebted because of their education loans. Many feel guilty, they have a sense of failure when they cannot repay that would be unthinkable in a wage struggle. There, you know you are exploited, you know your boss, you see the exploitation, you have your comrades. Whereas as a debtor, you say ‘oh my god I miscalculated,’ ‘I took more money than I should have’ etc.

Image: Blockades by El Barzon activists, 2013

Image: Blockades by El Barzon activists, 2013 That’s why debtors’ movements are so important. The first big debtors’ movements developed in Latin America. Perhaps the most important was El Barzon, that developed in Mexico in the late 1980s. It was a powerful movement composed mostly of small traders, small businessmen who had got some loans from the banks. El Barzon is the piece of leather that keeps together the wooden yoke between oxen. It’s a symbol of slavery. You have a yoke on, that’s the debt. They built a movement that organised large demonstrations all over Mexico, they marched in the streets with their pockets turned inside out to show that nothing had been left to them.

Also there were massive protests by women against microfinance in Bolivia in 2002. Women came from different parts of the country and laid siege for 90 days to the banks in La Paz demanding an end to their debt, stripping themselves to dramatise the fact that they had been reduced to almost nothing. We can see that debt can provide a common ground for different struggles.

Self-Reproducing Movements MV: The question of the durability and expansion of social struggles is something you have discussed in terms of building ‘self-reproducing movements’. Movements for which reproduction is a necessary aspect of transforming social relations in the present, and thus is constitutive of the political horizons of the struggle. I guess my question here would be operating backwards and forwards. Given the decomposition of the pre-capitalist ‘proletariat’ as experienced in something like the witch hunts in early modern Europe, the colonies and many places undergoing enclosures or ‘primitive structural adjustment’ at the current moment and in the recent past, I’m interested in what kinds of solidarity or re-composition you can envision which are far ranging enough for this not only to be resisted, but for capital to no longer be able to impose its reproductive crises as the breakdown of our social reproduction.

SF: One example that comes to mind is what has taken place in some countries of Latin America, where in response to the brutality of neoliberal economic policies, thousands of people are constructing new forms of reproduction outside of the state. As Raúl Zibechi writes in Territories In Resistance (2012), in Latin America, in the last decades, the struggle for land has turned into a struggle for control over a territory, where to practice autonomous forms of reproduction and forms of self-government, as in the case of the Zapatistas or the Movement Sans Terre (MST) movement in Brazil. In Bolivia too, the massive struggles that took place in 2000 against the privatisation of the water system reached such a level of co-ordination and co-operation between the different indigenous populations – the Quechua in the Cochabamba area, the Aymara in El Alto – that there was the possibility of establishing forms of communal caretaking and self-management of formerly public resources. This is taking place in Latin America because through the long struggle against colonial and neo-colonial domination people have maintained and created strong co-operative forms of existence which we certainly no longer have.

This is why the idea of creating ‘self-reproducing’ movements has been so powerful. It means creating a certain social fabric and forms of co-operative reproduction that can give continuity and strength to our struggles, and a more solid base to our solidarity. We need to create forms of life in which political activism is not separated from the task of our daily reproduction, so that relations of trust and commitment can develop that today remain on the horizon. We need to put our lives in common with the lives of other people to have movements that are solid and do not rise up and then dissipate. Sharing reproduction, this is what began to happen within the Occupy Movement and what usually happens when a struggle reaches a moment of almost insurrectional power. For example, when a strike goes on for several months, people begin to put their lives in common because they have to mobilise all their resources not to be defeated. At the same time, the idea of a self-reproducing movement is not enough, because it still refers to a particular population – the movement – while the goal is to create structures that have the power to re-appropriate the ‘commonwealth’ and that requires what Zibechi calls ‘societies in movement’.

Commons and Communism M: What is the relationship between commons and communism? Is communism an expanded common? Are the commons just about reproduction? Given your rather positive conception of reproduction as capable of containing within itself the germs for revolution how do you separate between social, potentially revolutionary and capitalist reproduction? That is, what is there in the commons that is not just more sustainable than but actively antagonistic to capital and the state?

SF: Commons and communism. Well, communism is such a big term, but if we think of communism in the sense established by the Marxist-socialist tradition, then one difference is that in the society of the commons there is no state, not even for a transitional period. The assumption that human emancipation or liberation has to pass through a dictatorship of the proletariat is not part of the politics of the commons. Also a society of commons is not premised on the development of mass industrialisation. The idea of the commons is the idea of reclaiming the capacity to control our life, to control the means of our (re)production, to share them in an egalitarian way and to ‘manage’ them collectively. The reconstruction of our everyday life, as a strategic aspect of our struggles, is a much more central objective in the politics of the commons than it was in the communist tradition. Is communism an expanded common? Not if we define it within the parameters of the Marxist tradition. But Marx’s description of communism as a society built on the association of free producers is compatible with it. Moreover the late Marx seems to have become convinced that commons, for example the Russian communes could become a foundation for a ‘transition to communism’, even though he believed this would be possible only if there would be a revolution in Germany, or other parts of Europe, providing a technological know-how, so that the Russian communes wouldn’t have to go through a capitalist stage. The commons means sharing the use of the means of reproduction, starting with the land, and creating co-operative form of work. This is already beginning to happen. In Greece and Italy, now, on the model of Argentina, workers that have been laid off are taking over factories and trying to run them in a self-managed egalitarian way to produce for people’s needs, rather than for profit.

I do not agree with Marx that capitalism enhances the co-operation of labour. I don’t think it does even in the process of commodity production, but it certainly does not in the process of social reproduction. Capitalism has developed a science of ‘scooperation,’ a term that I have taken from Leopolda Fortunati's The Arcane of Reproduction. An example is the urban planning that took place in American cities after WWII when the capitalist class confronted a working class that for 20 years or more had had a collective experience – first during the Depression, when people took to the road, creating hobo jungles, then during the war, in the army – and was now coming back from the war restless, questioning what they had risked their lives for. 1947 saw the highest number of strikes in the history of the United States, only matched by 1974. So, they had to ‘scooperate’ these workers and that’s what the new urban planning did with the creation of suburbia, like Levittown. It sent workers to live far away from the workplace, so that after work they wouldn’t go to the bars and instead would go directly home. They planned every detail of the new homes politically. They put a lawn in front of the houses for the man to mow in his spare time, so he would keep busy instead of going to a union hall. There would be an extra room for his tools – these were all instruments of scooperation.

ScooperationMV: Could you define what you mean by ‘scooperation’? I haven’t heard that term before.

SF: It is disaggregating workers, preventing them from developing the kind of bonding that results from working together and in the case of workers who had been in the war it was breaking down the deep sense of solidarity, brotherhood, they had developed. You can see it in the movies of the late 1940s. The soldiers are coming home after living together and risking death together for months, and then they separate, he has his wife, he has the girlfriend, but the women have become strangers to them. So these movies portray the crisis of the returning GI, and how do you prevent it from generating some sort of rebellion? This is why, home ownership, giving them a little kingdom, with the wife always at home, sexy with the apron on and all that, were so important. Levittown was constructed as a buffer against communism. This is the capitalist reproduction: Levittown. Now they have the opposite problem. My sense is that now they confront a working class that has a house, or at least assumes that the house is its entitlement, whereas they want a large part of the working class to be nomadic and move wherever companies need it. The attack on the house is not only a product of financial speculation. I think it is an attempt to create a workforce that is more mobile. Now their problem is ‘mobilising’ this worker. That’s an important difference. Clearly we have to build collective ways of reproducing ourselves so we are less vulnerable to these manipulations. Moreover reproductive work has to be done on the basis of expanded communities, not necessarily extended families but expanded communities, because reproducing human beings is very labour intensive and we can destroy ourselves in the process, as it is happening with so many women now, who live in a state of permanent crisis – of permanent reproductive crisis.

Strike Debt and the Rolling Jubilee MV: The following are a few examples that maybe you could elaborate on, what you think about their strategic aspects or contradictions. This would be about the Strike Debt campaign and about the Rolling Jubilee. Here we have a weird nexus between the politics of social reproduction and systemic reproduction, so on the one hand you are helping people who owe debt but you are also helping people who own debt at the same time because when you are buying the debt, you are also buying the banks’ debt... It’s impossible to say whose debt it is.

SF: The Rolling Jubilee will liberate a number of people. But the key thing is that it puts the question of student bondage on the map, in front of all America. I agree with Audre Lorde that: ‘The master’s tools will not dismantle the master’s house’. So we are not expecting to win that struggle through rolling jubilees. Rolling jubilees is a moment, a tactic, in a much broader struggle. But it has given this struggle a nationwide presence it didn’t have before. This kind of publicity is very good because it shows the world the mercenary character of this capitalism that destroys the youth's future, and makes money selling education. It’s an effective tactic; it serves to broaden the struggle, make it visible and put the authorities on the defensive. It says there is a generation of youth who have been turned into indentured servants of banks and collection agencies.

MV: It’s really important that you say that, also because there was an editorial by Charles Eisenstein in the Guardian, saying that a debt jubilee will restore growth, this is completely apolitical, it’s neither left nor right.

SF: They love that... Before Strike Debt there were already two student organisations dealing with loan debts, but they had a different approach to it. For one organisation the strategy was consumer protection. Their position was that as consumers of education we should have the ‘right to bankruptcy’ –which now is denied. The other argued that if you cancelled the student debt, which is now 1 trillion, you would boost growth. This is a kind of Keynesian strategy. Strike Debt is much more powerful, because it says that we should not pay, because this debt was created under duress. Students were told they had to have an education, but they had no way of doing it except by falling into debt. And the debt is not legitimate because education is not a commodity and should not be bought and sold. This approach has a very different political implication. As for Rolling Jubilee, it is a time bound tactic, but for the moment it’s useful. People are thinking of a caravan to bring Strike Debt throughout the country and build a nation wide network of groups.

Silvia Federice Wages for Housework MDR 18.11.2013 from May Day Rooms on Vimeo. MV: I found it quite an exciting and interesting thing too when reading this editorial, where a guy is promoting it by saying: ‘Financial institutions and people in debt are on the same side’. This is a bit ridiculous in the context of a political struggle.

Debt for Life George Caffentzis: They don’t make a distinction between capitalist debt and proletarian debt.

MV: But is that central to the Rolling Jubilee platform, or is that just this guy posing it this way?

GC: No. The Rolling Jubilee comes out of Strike Debt and it is basically saying that proletarian debt is radically different from the debt of the capitalists. The conditions for liberation from it are also quite different and the consequences are different. What’s happening in this period in history is that in order to satisfy our most basic life requirements we have to get into debt.

SF: Many people live on credit cards today, , going from one credit card to another. It’s like microfinance, where people must have multiple money lenders. In either case, you live on borrowed time until the moment when you cannot do it any longer. In the case of microfinance, when you do not pay back they put your picture in the streets or on the door of the bank to shame you. In the US, they turn you in to the collection agencies. So some people have gone underground – they have become refugees from the debt – because the collection agencies call you day and night.

GC: Now we understand what collection agencies are all about. They buy debt on a secondary market, so the big banks and financial institutions when they have trouble collecting sell the debt to them for 1 to 5 percent of its original value So, you ask yourself: ‘how much is this debt?’ You’re being tortured to allow the collection agencies to make the 95 percent difference. Again you ask yourself: is the debt $100,000 or is it $5000? What is the real debt?

Anthony Davies (Mayday Rooms): Can I ask a question about the normalisation of debt. For example, the banking industry has experienced some difficulty cultivating personal debt, even quite recently in Turkey and elsewhere due to the sense of shame and stigma associated with debt. So, I’m wondering how this might have developed incrementally, here in Britain and the US in the post-war period. How workers got used to the idea of being in debt, how that experience become an entirely normalised aspect of life in general?

SF: That’s an interesting question that requires some research. As far as I know, the promotion of indebtedness begins at a time when workers still have some social power. Buying on instalment began in the ’20s and then expanded after WWII. Incentivising workers to buy on credit was a way of controlling their future. It was also a way of diffusing class antagonism by boosting a consumer culture, the assumption being that workers would be employed and could pay back. The novelty was that buying on credit was an inversion of capitalist policy. Generally, in capitalism you work first, then you get paid. This was a reversal. In different ways this policy continued until the 1980s. Today’s indebtedness is different however. Today people go into debt not because they are sure about their future earnings but because they cannot get by or get certain social services without borrowing from the banks or using credit cards. For a lot of people the response to cuts in employment has been the credit cards and other forms of debt. So today debt is above all a refusal of impoverishment. The point in common between these two phases of indebtedness is that in both cases debt controls and shapes our future. Still, we need to better understand the relation between debt and the class struggle – how workers have tried to use debt. Even in recent times, many workers, especially those like black/female workers, who in the past found it difficult to secure mortgages, took advantage of the relative ease with which mortgages were granted to have access to housing. In fact many of those who defaulted because they were given sub-prime mortgages were black women, often single mothers, who had always been excluded from the mortgage market.

AD: A question around entrepreneurship, particularly serial entrepreneurship and the way in which bankruptcy law has been hauled into a boom/bust entrepreneurial process. At what point did it become embedded that borrowing and bankruptcy are synonymous?

GC: Bankruptcy only begins in the United States in the 19th century, around the time of the Civil War. Up until that time, in most states, there was debtors’ prison – if you defaulted, you went to jail. That was one part of the story. Towards the end of the 19th century, bankruptcy became established for the capitalists. It was extended to workers when the working class began to have some collateral. You couldn’t take out a loan unless you had some collateral. Workers began to have some collateral only when the wage became an institution. For a while personal bankruptcy was allowed and many workers and students used it. At first it was relatively easy to use. But by about 2005 there was a change in the level of stringency applied to it. Now, you have the worst of all possible worlds, because you still need a house, or a car, etc., and have to use a credit card but you do not have a guaranteed wage and it is much more difficult to go bankrupt. Moreover, students cannot go bankrupt when they cannot pay back the loans they have taken. They are the only case in which bankruptcy is ruled out.

AD: If you take the legislation around Company Voluntary Arrangements (CVA's) for example and its introduction into Britain from the US in the mid-1980's, you find that there's a link to crisis. At each point, there's a turn of the screw: in the economic recession of 1992, then in the early 2000s you find the legislation around CVAs being adapted and tweaked to suit the interests of employers – until you get to the late 2000s and the current situation, where contractual obligations can be ripped up, workers laid off and redundancy payments withdrawn or transferred.

GC: Now there is the possibility of a jubilee, but the question is whether the jubilee will open a new page or simply cancel the existing debts and in time re-propose the same situation.

SF: I doubt there will ever be a jubilee. But they may reduce student debt because education is a sensitive matter. However there is a part of capital that wants youth to be educated directly by the employers. They would love to have specialised academic institutions, like a mining university, a university serving energy companies.

MV: You were talking at the Historical Materialism plenary about cleaners and an organising drive where they decided to co-operate with employers against the state to get more resources from the state. I just wanted to ask you to explain that a bit more.

SF: Domestic workers are making a big struggle in the US. They are fighting to be recognised as workers, because the labour laws adopted in the 1930s exclude domestic work as work. In November 2010, for the first time in New York, an organisation of domestic workers, Domestic Workers United, had their work recognised as work. Amazing, isn’t it? The next thing they had to do was to make sure it would be implemented. So the same domestic workers are now striving to create community structures that can help enforce this Bill of Rights and function like watchdogs. They also want to organise in alliance with the employers, to be able to confront the state and force it to place the appropriate resources at the disposal of reproductive work. They believe it is not in the interest of employers to underpay them and to force them to work in wretched conditions. The argument is that a tired nanny, who is overworked, who is anguished because her family is far away, who cannot go on vacation, and is missing her son, cannot properly do the work expected of her. It is the same argument nurses have made. The hospitals try to put the patients against them when, for example, they want to go on strike. But what the nurses say is that ‘if we work 20 hours a day, we’re not going to be able to see what medicine we are giving you.’ In other words, it is in the interest of the patients that workers fight for better conditions and to support their struggle.

MV: But domestic workers are being paid by the employers, not by the state?

SF: They are paid by the employers, but in many parts of Europe in the ’80s and ’90s the state began to give money to families to be able to take care of non-self-sufficient elderly. For example, in Italy they introduced the salario d' accompagnamento. An elderly person, blind, or otherwise disabled would receive up to €500 a month to pay someone to take care of her. I guess, you could call it a sort of wages for housework. Of course it is very little, but it is a start.

In California, instead, last year, Governor Brown rejected a domestic workers Bill of Rights arguing that it would hurt people with disabilities, because, he said, they would not be able to pay higher rates. In other words, domestic workers have to work for low wages and accept there is a conflict of interest between them and the people they care for, and have to sacrifice their well being because the state had no intention of providing the type of resources that could guarantee to them and the people they care for a good life.

MV: It’s the Walmart argument. That workers benefit from low prices because they get paid so little themselves.

Silvia Federici <dinavalli AT aol.com> is a longtime activist, teacher and writer. She is the author of Revolution at Point Zero. (2012); Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation (2004) now translated into several languages, and co-editor of A Thousand Flowers: Social Struggles Against Structural Adjustment in African Universities (2000)

Marina Vishmidt <maviss AT gmail.com> Marina Vishmidt is a writer and editor. She has just completed a Ph.D. at Queen Mary, University of London on 'Speculation as a Mode of Production in Art and Capital'. She works mainly on art, labour and the value-form. She often works with artists and contributes to Mute, Afterall, Texte zur Kunst, Ephemera, Kaleidoscope, Parkett, as well as related periodicals, collections and catalogues. Info Silvia Federici,

Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist Struggle, was published by PM Press, August 2012,

https://secure.pmpress.org/index.php?l= ... tail&p=420The Wages for Housework: Silvia Federici Collection was deposited with MayDay Rooms January 2013, to browse the collection see:

http://maydayrooms.org/collections/wages-for-housework/ Full audio recording of the interview is available here:

http://snd.sc/ZibwmSAudio recordings by Rachel Baker

Footnotes1 Silvia Federici talk at Goldsmiths University took place 12 November 2012. Entitled ‘From Commoning to Debt: Microcredit, Student Debt and the Disinvestment in Reproduction’, an audio recording can be accessed here: http://archive.org/details/SilviaFederi ... 12-CpAudio