An excerpt from

My Cocaine Museum

Michael Taussig

chapter 2

my cocaine museumI ask a friend upriver in Santa María what happens to the gold he mines and sells. He says it goes to the Banco de la República in Bogotá, which sells it to other countries. "What happens to it then?" "I really don't know. They put it in museums…" His speech fades. Lilia shrugs. It's for jewelry, she thinks. And for money. People sell it for money. It goes to the Banco de la República and they get money for it…In a burst of self-righteousness, I ask myself how come the world-famous Gold Museum of the Banco de la República in Bogotá has nothing about African slavery or about the lives of these gold miners whose ancestors were bought as slaves to mine the gold that was for centuries the basis of the colony—just as cocaine is today? So what would a Cocaine Museum look like? It is so tempting, so almost within grasp, this project whose time has come…

Within grasp?

Project?

Where better, then, to start than with the twelve-inch-long bright red wrench, lovingly displayed on our TV screens in New York City last week, as described to me by my teenage son, an inveterate watcher of TV? Is not this oversize wrench the most wonderful icon for

My Cocaine Museum? I mean, where better to start than with the mundane world of tools, antithesis of all that is exorbitant and wild about cocaine, and yet have this particular tool, which, being so fake and being so grand, so far exceeds the world of usefulness that it actually hooks up with the razzle-dazzle of the drug world? How these two worlds of utility and luxury cooperate, to form deceptive amalgams that only people privy to the secret can prize apart, is a good part of our story and therefore of our museum too.

For according to U.S. federal prosecutors, gold dealers on Forty-seventh Street in Manhattan are paid by cocaine smugglers to have their jewelers melt gold into screws, belt buckles, wrenches, and other hardware, which are exported to Colombia, from where the cocaine came in the first place. U.S. attorney in Manhattan James B. Comey points to "the vicious cycle of drugs to money to gold back to money."

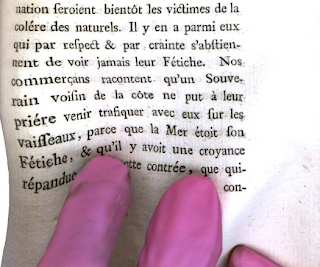

Could we not have predicted this, given what we already know about the tight connections in prehistory between gold and cocaine? The exotic and erotic gold

poporos in the Gold Museum have long unified the world of gold with the world of coca. Used to contain lime from crushed seashells and burnt bones so as to speed up the breakdown of the coca leaf into cocaine, the

poporo unifies the practical world with the star-bursting world of cocaine and cannot be too far removed from the beauty of the oversize red wrench, at once so practical and impractical. "On 47th Street, everything is on trust," says a jeweler, making it all the easier, it appears, for an undercover agent from the El Dorado Task Force who came saying he wanted to smuggle gold into Colombia and needed to change its shape. The jeweler replied to UC (which is how the undercover agent is now referred to) that he would provide gold in any shape UC wanted.

Any shape UC wanted.

How perfect is gold, the great shape-changer, the liquid metal, the formless form. How perfect for our Cocaine Museum to have such hefty metaphysical kinship with a substance that, like the language of the poet, can be twisted and tuned to the music of the spheres. I can think of only one other substance that rivals gold and cocaine in this regard and that is cement, once known as liquid stone, which now covers America.

Where better to start, then, than in the canyons of Gotham, with Wall Street brokers buying their drugs from a Dominican man in a nice suit in the men's room sniffing cocaine. At the same time across the East River at Kennedy Airport, there is a Chesapeake Bay retriever, also sniffing, urged on by its U.S. Customs-uniformed mistress, "Go, boy! Go find it! Good boy!" as small-statured Colombians draw back in horror at the baggage carousel when their clear plastic-wrapped oversize suitcases come lumbering into sight and smell—plastic-wrapped in Colombia by special businesses that come to your home the day before the flight to seal your baggage against a little slippage.

A real American decides enuf is enuf. The dog has gotten out of control, he decides, and he tells its handler to back off as the dog jumps up and down slobbering on his chest. "You have your constitutional rights," says the handler. "Here everyone is guilty until smelt innocent," and she urges the dog to leap higher. You need a large dog for this sort of work. The small ones may be smarter but get trampled on. Whoa! Watch out! Dogs and their happy masters and mistresses come running helter-skelter down the aisle as if out in the park for a romp. They must be thinking of the dogs leaping for red meat under the wings of the planes out on the tarmac far away at Bogotá. Lucky Third World dogs. When the animal is at play, the prehistoric is most likely to be snagged.

Sometimes they find a frightened Colombian they suspect of having swallowed cocaine-filled condoms before the flight. They force-purge the suspect. I mean, how many days do you think the DEA's gonna wait on some constipated mule? In the toilet bowl swim tightly knotted condoms like pairs of frightened eyes, blown up Salvador Dalí-like streaming out of the bowl, across the floor, and along the ceiling, showing the whites of terror as other condoms explode in the soggy blackness within the stomachs of couriers.

Far from the surefooted world of dogs, yet no less dependent on instinct because they cannot distinguish coca from many other plants, are the satellite images used to prove the success of the War Against Drugs, spraying defoliants onto peasants' food crops as well as onto coca, forcing the coca deeper into the forest and now over the mountains and into the Pacific Coast. The U.S. ambassador to Colombia has been quoted as saying, "It's quite possible we've underestimated the coca in Colombia. Everywhere we look there is more coca than we expected." Remember the "body counts" in Nam?

The noose is tightening, says the priest. Along with the cocaine come the guerrilla, and behind the guerrilla come the paramilitaries in a war without mercy for control of the coca fields and therefore of what little is left of the staggeringly incompetent Colombian state. You edge into a dark room with sounds of a creature in distress illuminated by a red glow casting shadows of vultures on the wall of the slaughterhouse early morning as amidst the smell of warm manure, the lowing of cattle, and thuds of the ax, poor country people line up closer together shivering to drink the hot blood for their health as the president of the United States of America signs the Waiver of Human Rights in the Rose Garden that releases one billion dollars' worth of helicopters fluttering out of the darkness like the bats the Indians made of gold, the caption to which tells us that being between categories—neither mice nor birds—bats signified malignity in the form of sorcery, and compares the helicopters with the horses of the conquistadores breathing fire and lightning on terrified Indians.

But the Indians were always good with poisons and mind-bending drugs such that high-tech solutions turn out to be not all that effective in the jungle, so don't despair: there's every chance the war and the massive economy it sustains will keep roaring along for many years yet. Speaking of Indians, here's a familiar figure to greet you, that huge photo you see in the airport as you walk to immigration of a stoic Indian lady seated on the ground in the marketplace with limestone and coca leaves for sale and in front of her, of all things, William Burroughs's refrigerator from Lawrence, Kansas, with a sign on its door,

Just Say No, as an Indian teenager saunters past with a Nike sign on his chest saying

Just Do It and a smiling Nancy Reagan floats overhead like the Cheshire cat gazing thoughtfully at an automobile with the trunk open and two corpses stuffed inside it with their hands tied behind their backs and neat bullet holes, one each through the right temple and one each through the crown of the head.

El tiro de gracias. Professional job, exclaim the mourners crowding around the open coffin and holding the neatly dressed children high for a better view. "I know when I die," I say to Raúl, "I want it to be here in this pueblo with these people around me." He looks at me oddly. I have scared him.

One of the bodies is Henry Chantre, who while doing his military service in the Colombian army used to pick up and transport drugs into Cali for his officers—so they say—and when discharged got into trafficking himself, a shiny SUV, a blond wife, handsome little children, and one day a deal went sour and he was found stuffed in the trunk of an abandoned car by the bridge across the Río Cauca. A long way from Manhattan's East River. In one sense. Strange, these rivers, so elemental, first thing the conqueror does is find a river snaking its way into the heart of darkness and all of that, for trade, really, canoes, rafts, that sort of thing, rail and road an afterthought decades or centuries later, water spanning the globe, the bridge spanning the river connecting Cali to this little town south, where Henry Chantre lies staring at you, the town milling round, the bridge being where most of the bodies end up getting dumped, heaven knows why; what weird law of nature is this, the river, the bridge, why always the same spot, macabre compulsion to dump bodies in the burnt-out cars and gutters there in the no-man's-land by the bridge between categories, like the bats, neither bird nor mouse, sanctified soil teeming with chaos and contradiction here by the river where black men dive to excavate sand for the drug-driven construction industry in Cali. Father Bartolomé de las Casas, sixteenth-century savior of Indians in the New World, wrote passionately about the cruelty in making Indians dive for pearls off the island of Margarita in the Caribbean. Nowadays, long after African slavery has been abolished, the slavery that replaced the slavery of Indians, it's considered routine to dive for sand, not pearls, the strong ponies so obedient braced against the current, carrying wooden buckets.

We need figures, human figures, as strong as these squat ponies braced against the current, and in the early morning mist by the river comes in single file the guerrilla, who, except for their cheap rubber boots and machetes, look the same as the Colombian army, which looks exactly the same as the U.S. Army and all armies from here to eternity most especially the paramilitaries, who do the real fighting, slitting the throats of peasants and schoolteachers alleged to collaborate with the guerrilla, hanging others on meat hooks in the slaughterhouse for days before executing them, not to mention what they do to live bodies with the peasants' own chain saws, leaving the evidence hanging by the side of the road for all to see, and worst of all, me telling you about it. Hence the restraint in the display case in our Cocaine Museum with nothing more than a back ski mask, an orange Stihl chain saw, and a laptop computer, its screen glowing in the shadows. When they arrive at an isolated village, the paras are known to pull out a computer and read from it a list of names of people they are going to execute, names supplied by the Colombian army, which, of course, has no earthly connection with the paramilitaries. Just digital. "It was a terrible thing," said a young peasant in July 2000, in the hills above Tuluá, "to see how death was there in that apparatus."

The paras are frank even if they like to be photographed wearing black ski masks despite their being hot and prickly. As of July 2000, some 70 percent of the paras' income, so they as well as the experts say, comes from the coca and marijuana cultivated in areas under their control in the north of the county, drugs that will make their way stateside. Yet up till that date, at least, the paras get off scot-free. Their coca was rarely subject to eradication, and the government's armed forces had never, ever confronted the paramilitaries. Instead the thrust of the U.S.-enforced war was to attack the south where the guerrilla are strongest and leave the north free. The War Against Drugs is actually funded by cocaine and is not against drugs at all. It is a War for Drugs.

Our guide motions to the ripples spreading over the river where corpses are daily dumped, and men dive for sand for the remnants of what was once a thriving industry, building the city of Cali, rising rainbow-hued through layers of equatorial sunbeams thickened by exhaust fumes. Transformed by drug money invested in high-rise construction and automobiles, the city now wallows in decay, with many of its apartment towers and restaurants empty. Nothing like cocaine to speed up the business cycle.

To the south of the city, in the next room of our Cocaine Museum, are the remains of peasant plots like bomb craters filled with water lilies in the good flat land from which the earth has been scooped out eight or more feet deep so as to make bricks and roof tiles for when the building boom in the city was in full swing. This rich black soil was once the ashes of the volcanoes that floated down onto the lake that was this valley in prehistoric times. Peasants sold it, their birthright, taking advantage of the high prices for raw dirt and because agribusiness created ecological mayhem with their traditional crops. Then the boom stopped and now there is no work at all. There is no farm anymore. Just a water hole with lilies that the kids love to swim in.

And to tell the truth, for a lot of people even if there was "work" in the city, nobody would want it. Dragging your arse around from one humiliating and massively underpaid job to another—less money, really, than the women get panning gold on the Timbiquí (Can you believe it!). That's all over now, the idea of work work. Only a desperate mother or a small child would still believe there was something to be gained by selling fried fish or iced soya drinks by the roadside, accumulating the pennies. But for the young men

now there's more to

life, and who really believes he'll make it past twenty-five years of age? If they don't kill each other, then there's the

limpieza, when the invisible killers come in their pickups and on their motorbikes. At fourteen these kids get their first gun. Motorbikes. Automatic weapons. Nikes. Maybe some grenades as well. That's the dream. Except that for some reason it's harder and harder to get ahold of, and drug dreams stagnate in the swamps in the lowest part of the city like

Aguablanca, where all drains drain and the reeds grow tall through the bellies of stinking rats and toads. Aguablanca. White Water. The gangs multiply and the door is shoved in by the tough guys with their crowbar to steal the TV as well as the sneakers off the feet of the sleeping child; the

bazuco makes you feel so good, your skin ripples, and you feel like floating while the police who otherwise never show and the local death squads hunt down and kill addicts, transvestites, and gays—the

desechables, or "throwaways"—whose bodies are found twisted front to back as when thrown off the back of pickups in the sugarcane fields owned by but twenty-two families, fields that roll like the ocean from one side of the valley to the other as the tide sucks you in with authentic Indian flute music and the moonlit howls of cocaine-sniffing dogs welcome you to the Gold Museum of the Banco de la República.

Something like that.

My Cocaine Museum.

A

revelación.