Capital and Abortion Pt. 2, Marxist Feminism Must Account For Race

Posted: June 7, 2011

In my other post, Abortion banned in the U.S. = In Capital’s Best Interest?? < shesamarxist.wordpress.com/2011/02/16/abortion-banned-in-the-u-s-in-capital’s-best-interest/>, I posited some theoretical frameworks for considering whether capital has a material interest in the struggle over abortion and birth control.

In Louisiana, Alabama and Mississippi, lawmakers are attempting to ban abortion altogether, with the exception of cases where a woman’s life is at stake, by redefining personhood to consider life beginning at conception. This kind of redefining of personhood would effectively make abortion a crime of murder. In Missouri, HB213 was passed banning abortion after 20 weeks of gestation except in medical emergency or when fetus is not viable.

[If you scroll all the way to the bottom of this post, I have a larger list of current moves being made to limit abortion and reproductive access for women.]

In this post, I want to get a bit deeper into some of my thoughts on this topic. In this post I want to basically put forward the main argument of the paper I co-presented at the recent NYC Historical Materialism conference: Marxist feminism’s attempts to understand the material basis of women’s oppression have been hampered by its lack of a racial analysis. Basically, we can’t understand capital’s interest in controlling women’s lives unless we understand that capital does not just need a gendered division of labor, it needs a racial division of labor, and these divisions are critically reliant on one another.

Though I don’t want to unpack this entire argument (race and gender as interlocking and interdependent systems within the capitalist division of labor) in this piece, I want to begin to outline the pitfalls of traditional Marxist feminist theorizing and then demonstrate the way I have seen it address the question I raised in my last post: whether capital has an interest in banning abortion. Lastly I will conclude with an overview of how the kind of Marxist Feminist analysis I am advocating (one that centers a racial analysis) is better suited to approach the question of capital’s interest in abortion.

How Race-Blind Marxist Feminism Might Attempt to Understand Capital’s Relationship to Abortion:

Marxist feminism has done important work filling in the huge gaps in Marx’s work by theorizing about the economic quality of women’s reproductive labor in the home. In particular, feminists like Mariarosa Dalla Costa understood that women’s work in the home was devalued because it lacked a wage and was thus seen as “unproductive” labor. Dalla Costa argued that reproductive labor was actually involved in productive labor– its product was labor-power itself. However, the value of this realization quickly became subsumed within endless wrangling amongst Marxist Feminists as to what the implications were to considering reproductive labor either productive or unproductive. Did that mean that the husband was a mini-capitalist or a feudal landlord? Did that mean that women were directly exploited within capitalism and did that mean women were automatically proletarians with an interest in capital’s overthrow? What about ruling class women? All of this debating attempted to really understand the material ways in which women’s oppression was rooted in the capitalism’s reproduction– M – C – M.

To the extent that these Marxist Feminist debates centered their focus solely on the family as the reproducer of labor-power, without recognizing that the family and the way its internal division of labor is organized, are both shaped by the value of the labor power it is reproducing/maintaining, they have been deeply flawed. In other words, these Marxist Feminist debates have been hampered because they have often dehistoricized and homogenized the family as a social unit, not recognizing that the family’s relationship to capital is shaped powerfully by other important dynamics (such as the need for a racially hierarchical labor force). *The exception to this being the very important work done by Selma James, Maria Mies and Silvia Federici, particularly Mies and Federici, who I believe were some of the first feminists to bring a razor sharp Marxist analysis to not just gender but race and colonization, recognizing that one cannot analyze one division of labor without the other. Both Mies and Federici recognized the interrelationship between the reproductive/productive split (which gives gender its coherence) and the first world/third world split (the processes of colonization which give race its coherence). (My own Marxist Feminist perspective draws very heavily from Mies and Federiciespecially, which is why I was very excited to have Federici as a discussant on the panel at which my comrade and I presented some of this work!)

There are very clear limitations to trying to understand capital’s relationship to “women”, as a monolith, just as much as there are clear limitations to understanding capital’s relationship to the “family” as a generic social structure. If we don’t consider the fact that the family does not just reproduce labor-power, but labor-power of a particular caste, that is, labor-power of a particular race and nationality, we cannot explain the way that capitalism relates to “women”.

For example, if we were to look at the current attacks on birth control and abortion, in a way that was race-blind, we might be compelled to ask ourselves– why would capital want to limit women’s access to abortion at a time when there is a surplus population and sky rocketing unemployment? If we were to see the government attempts to limit and constrain access to abortion and reproductive services as an attempt to augment the labor force (a basic marxist-feminist orientation that sees the family as an economic structure and women’s roles as reproducers of labor-power) we will be confounded. Why? Because capital does not need more workers, per se. It needs more workers of a particular kind, and it needs a particular racial composition of workers.

Approaching the Question of Capital’s Interest in Controlling Women’s Reproduction, with a Racial Analysis

When I say a racial analysis is necessary to Marxist Feminist analysis of capital’s relationship to women, I mean we must have a class-based understanding of race. What does that mean? It means that from the beginning capitalism has relied on uneven competition that has been structured geographically/nationally (the first world needs a third world) and racially (slavery, jim-crow, migrant labor).

From the beginning capitalism relied on a racial division of labor in order for what we know to be the gendered division of labor, to exist. In order for capitalism to emerge and establish itself as a world order, it needed colonization and slavery. In other words, it needed to exploit some groups of people (brown, black and yellow) and expropriate them from their land and resources, in order to establish the system of wage-slavery within the centers of empire (like Europe and North America). Industrialization gave birth to the nuclear family or the privatized family, as we know it today, even as it was only limited to sections of the population. Nonetheless, the nuclear family with its corollary gendered division of labor is the established ideal within capitalism for two reasons: first, private property ownership (wealth accumulation) is passed down through familial lineage so there is a need for the marriage contract and inheritance. Second, the independent citizen that was established when white male suffrage was won in the U.S. (the right for white men to vote regardless of whether they owned property or not) has a built in assumption of a dependent within the home (the woman, housewife). Therefore these traditional gender roles are basically built into the ideal of the independent citizen–he is property owning, head of the family. As we know the bourgeois conception of citizen (abstract independent citizen devoid of class) is distinct to capitalism which needs to have “equals” (capitalists and worker) enter into the marketplace to exchange their “equal” commodity (labor-power for a wage). Even though later on in the project black men and women have gained access to citizenship, the concept of citizen is still built on the idea of an independent man with dependents in the home, and it is still dependent on the enslavement and exploitation of black and brown people (whose wealth, once appropriated makes the citizen ‘independent’).

Moving along, throughout U.S. history, the pitting of workers against one another on the basis of race has been critical to the stabilization and strength of the capitalist system. We now know that race is a mythology, and that it has no biological basis, but racial difference and racism is so key to capitalism because it is an easily internalized system of privilege in which people who are on the privileged side exaggerate their difference from racial minorities in order to hold on to the material privileges their skin color confers. Racial and national identity nicely flattens differences within groups (such as ahem gender and age) by uniting people in opposition to other groups, on the basis of shared privilege. Even today, capitalism relies on immigrant labor which is made cheaper because lack of citizenship rights makes workers more exploitable.

So let us return to our question — does capital need more workers? No. Not exactly. It needs more workers of a particular kind. Let me give two very salient examples:

1) The ageing-workforce problem

2) The browning of America problem

These are two problems in which we can see how attacks on women’s reproductive freedom may actually make more sense to capital then we may have originally thought.

The Ageing workforce & The Browning of America

There are a plethora of articles worrying about the quickly ageing populations and falling fertility rates within the industrialized world. It seems that the business world is very concerned about ageing populations for the following reasons: first, ageing populations lead to stunted economic growth, second, ageing populations present a large social cost for governments who must take care of elderly and sick, third, ageing populations mean a shrinking labor force. For example, in one fascinating article, the Economist writes:

It is tempting to think that some of the gaps in the rich countries’ labour forces could be filled by immigrants from poorer countries. They already account for much of what little population growth there is in the developed world. But once ageing gets properly under way, the shortfalls will become so large that the flow of immigrants would have to increase to many times what it is now. Given the political resistance to even today’s levels of immigration (as shown up in the recent elections to the European Parliament), that, alas, looks unlikely.

So individuals, companies and governments in rich countries will have to adapt. There are some signs the first two are beginning to do that. Many employers remain prejudiced against older workers, and not always without reason: performance in manual jobs does drop off in middle age, and older people are often slower on the uptake and less comfortable with new technology. But people past retirement age would not necessarily carry on in the same jobs as before. In Japan, where pensions are Spartan and lots of people are still working in their later 60s and even 70s, big companies like Hitachi have found ways of re-employing staff after retirement—but in a different capacity and, significantly, at lower pay.

Elsewhere employers have been less inventive. But retailers such as Wal-Mart or Britain’s B&Q, and caterers such as McDonald’s, have started hiring pensioners because their customers find them friendlier and more helpful. And skills shortages are already creating opportunities: in the past year or two a dearth of German engineers has caused companies to bring back older workers. Once labour forces start declining, from about 2020, employers will no longer have much choice.

So already we are getting a bunch of information: capital has an interest not just in controlling abortion and birth control but in stripping retirement funds so that older people are forced back into the workforce at higher rates of exploitation. But what is also telling is the admission of the role that immigrants play in supplementing the growth rate of the labor force. However, as the article indicates, there is political resistance to immigration. Why? I would wager that there is a political pressure on politicians to increasingly rachet up anti-immigrant scapegoating and hatred in order to quell the disatisfaction of white workers who are bitter about jobs being taken by immigrant workers (which does actually happen, but which is also inflated by racist rhetoric).

Another example of this can be seen in the Republican anxiety around the Browning of America. Rather than seeing the attacks on birth control and abortion as merely an attempt to make everyone reproduce, I would argue that the Republican attacks on abortion and birth control are more about recreating the Cult of Motherhood so as to put social pressure on white women to have more children. The recent census confirmed that the reproduction of the immigrant population is far surpassing the reproduction of the more affluent citizens (i.e. the Whites). Black and brown populations are reproducing at a far faster rate than white populations. In fact, so much so that it is a basically accepted fact that by 2050 the United States will be majority brown.

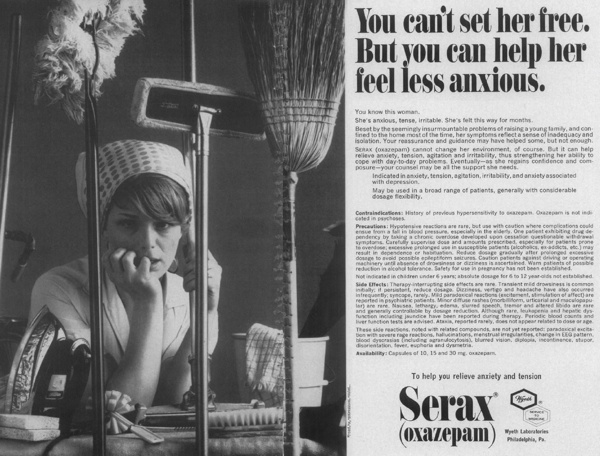

A graphic from a Racist White-Supremacist Website

What does that all mean? It means that for the first time in US history, whites will be a minority, and the browns don’t like Republicans too much. Did you know that California used to be a Red state? That was before Latinos became a majority in California. Now California consistently swings Blue. Republicans are incredibly aware of the way demographics affect their election prospects, that’s why they are constantly gerrymandering, or redrawing districts, in ways that maintain certain racial demographics amongst their constituencies.

Thus, I think in addition to this being a problem of a dwindling labor force, there is also a problem of maintaining a particular racial composition. As the racial composition in the country shifts, will the ways in which the ruling class relates to the population change? I am reminded of the ways in which slave control strategies differed in the Latin American colonies, versus the way they worked in North America. In Latin America, where slave populations often way outnumbered the Europeans, there was much more brutal policing and outright violence in order to keep that division in tact. So I think we have to think about the ways in which the ruling class is considering demographic changes, racially too, and how that translates into its attempts to control reproductive freedom.

In addition, don’t assume that just because Republicans are attacking birth control and abortion, that it means they are not simultaneously advocating or creating programs that have different plans for poor and working-class women of color. Take Louisiana for example, where state representative John LaBruzzo has openly and publicly advocated introducing a state funded program that would sterilize welfare recipients. This is the same lawmaker that is pushing the redefinition of personhood so that life is considered to begin at conception. In addition, some of the most conservative right-wing Republicans who are foaming at the mouth about abortion, were also previously staunch advocates of programs that were introduced throughout the 1990s that offered huge financial incentives to states that could reduce the birthrate of populations on welfare. That is why Norplant and other such programs were introduced, targeting working class women of color in particular.

The whipping up of cultural backlash against white women for using birth control too much, has a historical precedent as well. In 1901, Theodore Roosevelt went on the Radio and publicly chastised white women for using birth control. He called them selfish “race traitors” who were contributing to “race suicide”. He singled out middle and upper class women who pursued higher education instead of marrying and having children at a young age. As Linda Gordon writes, “he repeatedly condemned the selfishness, self-indulgence, and ‘viciousness, coldness, shallow-heartedness’ of a woman who would seek to avoid ‘her duty.” These women were seen as abandoning their “feminine” role as wives and mothers and, by challenging the gender division of labor they were in danger of destabilizing the racial one. Roosevelt’s fear was definitely provoked by the large numbers of migrant workers streaming into the U.S. at that time, whose cheap labor was critical to the health of the nation. Gordon explicitly describes how anxieties around immigrant rates of reproduction were related to concerns about class tension amongst workers. By chastizing white women for opting out of motherhood, Roosevelt was able to stigmatize immigrants, ramp up racism, while also putting pressure on white women to reproduce and be breeders of “the good citizens” so important to the nation. In other words, the racial composition of the working class was at stake. In addition to being adamantly against birth control for white privileged women, Roosevelt was a fervent supporter and advocate of eugenics.

Though eugenics is often discussed as a racist strategy, it is not often discussed as a strategy that was used to neutralize class struggle by emphasizing scientific racism, by literally deterring intermixing among races of workers, among other things. Eugenics often arose at a time when state hospitals appeared and there was a desire to cut and constrain the cost of state-run hospitals and mental facilities. The fear Roosevelt whipped up had large implications for how feminists would shape their birth control campaign in the future. For example, Margaret Sanger, (the crusader for birth control) as many people may or may not know, originally came from a working-class Irish family with 12 brothers and sisters. Sanger saw her working-class mother oppressed by an inability to control her reproduction. Sanger originally started her birth control campaign with the demand that women be given the freedom to control their sexuality and their bodies. This was an unpopular demand amongst middle-class white women reformers at that time (the majority of feminists) who had a vested interest in their roles as Mothers, because Motherhood afforded a woman a high degree of respect and power at a time when women in the workforce was not wide-spread and working women were degraded as unwomanly.

As a result, Sanger was forced to jettison her original argumentation for birth control on the basis of women’s right to control their own sexuality. Attacks on Sanger by both feminists at the time who emphasized the moral importance of respectability and by the larger conservative climate hostile to birth control as race suicide, prompted Sanger to change her rhetoric. Eugenics as a way of social betterment by preventing lower classes from reproducing gave the birth control movement a way of establishing itself as an acceptable moral issue because it did not challenge male privilege or right to women’s bodies. “Sanger…promoted two of the most perverse tenets of eugenic thinking: that social problems are caused by reproduction of the socially disadvantaged and that their childbearing should be deterred. In a society marked by racial hierarchy, these principles inevitably produced policies designed to reduce Black women’s fertility” (81). It is here that we can begin to see the ways in which the racial division of labor props up the gendered division of labor and vice versa, though I will get into that more in later posts.

In addition I can’t help but wonder whether the ruling class is worried about the ageing population of its professional workforce. In today’s globalized economy, the ‘first world’ is home to the ‘coordinating class’. As production of actual commodities has left the first world, we have seen what Saskia Sassen calls the rise of global cities– the nerve centers of capitalism where professionals work with computers to coordinate the now expanded division of labor all over the world. This population is ageing at a way higher pace than people of color. White upper middle-class families are way smaller and reproduce much less than families of color.

I have been reading in the Economist that a lot of financial analysts are worried about the fact that people retire too early and thus there is going to eventually be a dearth of people who are going to fill those professional jobs. I think that the ruling class wants to keep the coordinating side of the working (upper middle) class white, and it prefers to use people who can subsidize their own education to participate in that class. It would take tremendous resources to train and educate working class people to become professionals and managers and coordinators of global capital, versus middle class families who can pay for their kids education with no help from the state. This is just a theory. Whether or not it is a conscious strategy, the elimination of public education more or less will have the same effect as if it were.

Much of the thinking and theorizing that I review in this post was produced in conversation collaboratively within the Bay Area Marxist Feminist group(s) I am a part of. <3

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Attacks on Reproductive Freedom Continued:

In Texas, about a month or so ago, Governor Rick Perry recently signed a bill into law that requires women seeking abortions to have sonograms beforehand. These kind of legislations always irk the hell out of me because they are designed to intimidate, shame and terrorize women who choose to have abortions. I will never forget the time I accompanied my best friend to get an abortion and the doctor asked if we wanted to keep a photograph of the ultrasound picture. My friend and I both looked at him in amazement and my friend luckily spoke up and said ‘No, thank you’ in a rude enough voice to satisfy my urge to say out loud what I was thinking in my head– ”yeah, do you think we can get that in wallet size, you insensitive SOB?”

Anyway, the point of all this is these laws are directly disrespectful and abusive to women and our intelligence. YES WE SAID WE WANT AN ABORTION MOFO, I don’t need you to DESCRIBE the FETUS TO ME. Yes that’s right, the law requires doctors to DESCRIBE the fetus to women. Here’s a quote from the Miami Herald:

The law, which takes effect Sept. 1, requires doctors to make the image of the fetus, and the fetal heartbeat, available to a woman, although she may decline to see or hear it.

Doctors must describe the fetus, noting the size and condition of limbs and organs. The law also requires women to wait 24 hours after the sonogram to have an abortion, unless they live more than 100 miles from an abortion provider. In that case, they have to wait two hours.

This kind of restriction has already been passed in Oklahoma and is under consideration in Alabama. In North Carolina, a Republican measure is seeking to further reduce abortion access by imposing state-mandated counseling for any woman who elects to have an abortion, in addition to a 24-hour waiting period (as if being forced to look at the ultrasound wasn’t bad enough!). House Majority Leader Paul Stam blatantly called women idiots when he argued that this measure is necessary for women “to be medically informed”.

In Indiana, Governor Mitch Daniels signed into law HB 1210, a law which along with requiring women to look at her ultrasound picture and hear the heartbeat of the fetus, stripped existing and future Medicaid payments for “any entity that performs abortions or maintains or operates a facility where abortions are performed.” Essentially, this bill banned funding for 28 Planned Parenthood’s clinics across the state of Indiana — a blatant attack on poor and working class women of color and their access to healthcare period. The majority of what Planned Parenthood provides is not even abortion but pap smears, general exams, etc. The federal government has warned Indiana that the ruling is unconstitutional and is threatening to withhold the federal funding of the state’s Medicaid program if the bill is not overturned- that’s four billion dollars of healthcare funding at stake. A federal court is currently reviewing the Indiana law, the outcome of which will definitely have country-wide implications.

The attempt to cut public funding for abortion and reproductive health is a common trend in over 20 different states. In Virginia, Governor Bob McDonnell is seeking to ban abortion coverage by the state health insurance.In Ohio, lawmakers are considering a ban in the state that would block any publicly funded hospital or clinic from providing abortion.

In Utah, lawmakers have passed three laws which, collectively, “increase accountability and visibility of medical providers and clinics performing elective abortions, buttress the rights of medical providers who object to providing elective abortions, and prohibit certain funding options for patients seeking such abortions.” Read more here.

In Pennsylvania, a law entitled House Bill 574 was passed, which forces health clinics to make mandatory changes to their facilities. Critics of the bill have argued that these changes are too expensive and will effectively force many clinics out of business, putting an undue burden on the remaining facilities offering abortions.