http://www.coloursofresistance.org/532/ ... esistance/the healing journey as a site of resistance

by billie rain“Addressing our individual and collective suffering, we will find ways to heal and recover that can be sustained, that can endure from generation to generation” (hooks, 1995, 145).

I am real. I am a woman who, as a child, was subjected to torture so beyond my comprehension that it literally split my psyche. It was decided by the inside system that if we did survive what we saw so many die from, our stories and those of the other children who did not live would not be lost. By sharing and theorizing on these painful experiences, I hope to give voice to the healing journey that has been necessary for me to embark on in order to fully claim them as sites of resistance, and to understand them in a larger sociopolitical context. To connect the body, mind and spirit, who were severed long ago.

When my abusers were raping me, they had me convinced that nobody would believe me if I told, and if that didn’t deter me, they would kill me. I have struggled to understand what would motivate people to such sickness but in a way it doesn’t matter, on an individual level, why they did it as much as that it happened and I survived. The search itself has led me to greater understandings and helped me to understand that I am part of something greater than myself.

In her book

Thinking Class, Joanna Kadi writes:

Child sexual abuse teaches us lessons about power- who has it and who doesn’t. These lessons, experienced on a bodily level, transfer into the deepest levels of our conscious and subconscious being, and correspond with other oppressive systems. Widespread child sexual abuse supports a racist, sexist, classist and ableist society that attempts to train citizens into docility and unthinking acceptance of whatever the government and big business deem fit to hand out (Kadi, 73).

My father was a presidential appointee under George Bush Sr. and several of my abusers were high-level government officials.

“There’s no reason in this whole wide world to harm a child, be it your hands or your words that do the abuse” (Loftis, 38). Child abuse is incredibly prevalent in the united states, and it happens on all levels of society, regardless of ethnic or economic status. Parents, relatives, community leaders and other adults physically, sexually and emotionally abuse children. Many are also victims of neglect. In 1996 more than three million reports of child abuse were made in the US, and “the actual incidence of abuse and neglect is estimated to be three times greater than the number reported to authorities” (Childhelp USA). Growing up in a violent home (and a violent culture), even if the violence is not directed at the child, is harmful to children. A formerly abused woman writes: “Growing up in a house with a batterer is like living in a war zone. You can be attacked at any time and there’s nothing a child can do to fight back” (Agtuca, 30). Children who grow up in abusive homes are likely to develop a dissociative disorder or Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, originally known as “shell shock” or “Vietnam syndrome”, as a result of witnessing or experiencing firsthand abuse.

One in three girls and one in four boys is sexually abused before the age of eighteen, and children with disabilities are four to ten times more vulnerable to sexual abuse than non-disabled children. I was severely sexually and physically abused for the first seventeen years of my life. Today I am legally and significantly disabled as a direct result of that abuse. No matter what I do to heal, I will most likely carry certain scars to my grave.

Sapphire, in her poem “MICKEY MOUSE WAS A SCORPIO,” writes:

my father,

lean in blue & white striped pajamas,

snatches my pajama bottoms off

grabs me by my little skinny knees

& drives his dick in.

i scream

i scream

no one hears except my sister

who becomes no one because she didn’t hear.

years later i become no one because it didn’t happen.-(Scholder, 113).

I know too many people, male and female, who were sexually abused as children. Most of them were not able to comprehend what happened to them or speak out about it until they were adults. Child sexual abuse is such a crime, not because it is illegal, but because of the incredible damages it does to a young mind, body and heart.

“Not all blows are made by the hand and not all whipping is done with a belt” (Loftis, 40). Public education about physical and sexual abuse is increasing, but many people still do not realize the damaging effects of emotional or verbal abuse. Andrew Vachss defines emotional abuse as:

The systematic diminishment of another. It may be intentional or subconscious (or both), but it is always a course of conduct, not a single event. It is designed to reduce a child’s self-concept to the point where the victim considers [her/]himself unworthy- unworthy of respect, unworthy of friendship, unworthy of the natural birthright of all children: love and protection (Sue’s Abuse Pages).

Many survivors of physical and sexual abuse report that the emotional abuse they suffered was far more damaging than the actual blows. “The bruises from his slaps would eventually heal and go away, but I’ll never forget the awful things he said…” (White, 10). When I was being sexually abused, the things said to me and the threats made damaged my self-concept and made me fear for my life if I told. In a poem I wrote: “Fucking me mentally/ so you could fuck my body.” To this day I struggle to disentangle myself from the horrible things my abusers said I was, on top of dealing with the damage that was created by their physical and sexual abuse.

Of all abuse perpetrated on children in the US, it is my belief that ritual abuse is by far the most silenced form. Chrystine Oksana defines ritual abuse as “methodical abuse, often using indoctrination, aimed at breaking the will of another human being” (Oksana, 36-7), and in a 1989 report, the Ritual Abuse Task Force of the Los Angeles County Commission for Women came to this definition:

Ritual abuse usually involves repeated abuse over an extended period of time. The physical abuse is severe, sometimes including torture and killing. The sexual abuse is usually painful, sadistic, and humiliating, intended as a means of gaining dominance over the victim. The psychological abuse is devastating and involves the use of ritual indoctrination. It includes mind control techniques which convey to the victim a profound terror of the cult members… Both during and after the abuse, most victims are in a state of terror, mind control, and dissociation (Oksana, 36).

There are many different kinds of cults in the US, ranging from the church of scientology to transcendental meditation to satanic ritual abuse cults. The media has given some attention to the issues of cults and mind control, but the coverage has been sparse and often sensationalized.

Many people do not want to accept that ritual abuse happens, especially not in the sacred family unit. Anna Richardson, a ritual abuse survivor, describes the mental somersaults one must go through in order to comprehend the realities of this type of sadistic and systematic abuse. “The threat of meaninglessness posed by ritual abuse, the ways it dislocates reality, disintegrates expectation- here is my father working in the garden, here is my father torturing a boy; here is the bank manager smiling across the counter, here is the bank manager in the woods drinking blood- is a real part of the damage it causes” (Richardson, 7). Unfortunately, ritual abuse is another hidden history/present that needs to be brought to public knowledge. Laura Davis writes: “You may have experienced torture and atrocities that are difficult to believe. That doesn’t mean they didn’t happen. It just means we have to stop being naive. We have to broaden our perception of evil” (Davis, 225). This perception needs to include the presence of ritual abuse in the US alongside slavery, lynchings, internment of Japanese-Americans during WWII, the women’s holocaust (i.e. Salem witch trials) and genocide of indigenous people in all the Americas and beyond.

Ritual abuse is not the only crime committed by those with power that goes without prosecution or acknowledgment by the mainstream. Many oppressed people and communities in the US have experienced severe oppression on the one hand, and the suppression and denial of our realities by the mainstream media and those in power on the other. Often it is common knowledge that the government knows the abuse is taking place but refuses to admit publicly that they have a role in perpetuating it. Three examples of this, which were admitted to after they had been brought to public scrutiny, are MKULTRA, COINTELPRO and Indian boarding schools. Many people here are probably familiar with the MKULTRA mind control experiments, funded by the CIA. COINTELPRO stands for counter intelligence program, was an FBI sponsored project which targeted groups and individuals working for social change, primarily in communities of color, with harassment, covert disruption, infiltration and sometimes even assassination. I believe that we the public do not know the full extent of either of these covert government projects. As part of the ongoing destruction of indigenous nations, lifeways and culture in the united states, Indian children were taken from their families and communities and forced to attend christian boarding schools. In these schools, they were forbidden to speak their languages and often beaten if they did so. Many children were subjected to ritualized religious abuse by the priests and nuns in the schools as a way of breaking their wills and destroying their sense of themselves as indigenous people. This is an obvious connection to the ritualized spiritual abuse that many survivors have experienced.

In her groundbreaking book,

Teaching to Transgress, innvoative black feminist and cultural critic bell hooks writes:

I came to theory because I was hurting-the pain within me was so intense that I could not go on living. I came to theory desperate, wanting to comprehend-to grasp what was happening around and within me. Most importantly, I wanted to make the hurt go away. I saw in theory then a location for healing. (hooks, 1994, 59).

I want to understand what kind of world allows people to torture their own children and get away with it. What kind of society rapes its children, puts them in closets, tells them they are worthless, less than nothing, brainwashes them into thinking that they deserve to be mistreated because they are inherently bad and evil. Splits their fragile minds so that they can be a model student, play with friends after school, and shipped off nights (or whenever) to witness and be subjected to evil beyond comprehension. I want to understand how a society can grow from the seeds of racial violence, genocide and rape. I want to understand how a society that claims liberty and justice for all can invest itself in the suffering of millions within its borders and across the globe.

I was brutally abused when I was growing up. I was in fear of my life constantly and the abuse was done in such a way that I didn’t even have conscious knowledge of it at the time. I have consistently intuitively understood injustice on a very personal level and that understanding carried over into my understanding of other injustices. Through the abuse that was perpetuated on my body, mind and spirit I came to understand that people are capable of murdering innocent children and babies– even their own family. The adults I was surrounded by were capable of raping me when I was obviously a helpless child. It is no shock to me that the United States government was/is perpetuating genocide here and in other places. It’s not shocking to me that these injustices happen in the world, because I come from a basic level of belief that atrocities happen. We create and support a shallow public culture, which places more emphasis on the ilusion of goodness than on goodness itself. Lets break down these illusions and deal with reality. As a survivor of ritual torture and government funded violence, from the core of my being I have always understood injustice. Child abuse reproduces structural inequalities and brands them onto children’s bodies and hearts. No one who has been abused has not experienced oppression.

When I was 18, I was transformed by my experiences with a group of young feminists in the punk music scene called riot grrrl. In the summer of 1991 I helped inititate all-girl meetings at a local punk activist house in the DC area, where I grew up. At the meeting I met young women who were motivated and willing to connect on a deeper level and find ways to challenge and heal from the wounds inflicted on our lives by sexism. It was the first time I had met with any group that was willing to talk openly about sexual abuse. At that point, a floodgate opened in me. I began to consciously articulate the sexual abuse I had experienced from infancy. The other women in riot grrrl believed me, supported me, and were outraged at what I had experienced at the hands of my sadistic father. Through riot grrrl, I was able to write and tell my own story, or what I remembered of it at the time.

One point of this healing journey is not just personal, but to use my personal narrative to create a better world. I want my story to be a jumping off point to critically understand what oppression is and how it relates to child abuse. I want you to make a commitment, if you have not already, to take responsibility for the kind of society you really want to live in. Any understanding you come to as a result of my words must push us forward towards concretely and physically transforming society. “A people’s revolution that engages the participation of every member of the community, including man, woman, and child, brings about a certain transformation in the participants as a result of this participation” (Guy-Sheftall, 154). I feel that my inner revolution that has manifested itself as healing from child abuse is inherently linked to larger global struggles against oppression.

“The more we have suffered in the past, the stronger a healer we can become. We can learn to transform our suffering into the kind of insight that will help our friends and society” (Hanh,

Touching Peace, 1992, 8 ).

Healing has manifested itself in my life as a form of resistance. My healing process is inherently a rejection of who the abusers told me to be. I was taught to turn my life over to people who controlled me through pain. They tried to control my self-concept, my body, the thoughts I was allowed to think, the experiences I could be conscious of. They taught me that the only way to survive was to either be in control or to be controlled. The main definition of power I was exposed to growing up was power-over. Now I am learning the meanings of power-with and power from within. Remembering, speaking out, and deciding for myself what I want for my life are acts of resistance. Building communities based on mututal respect, compassion and honesty is one step towards creating the kind of world I want my children to live in.

The word activism is centered on the word act. An act doesn’t necessarily have to be a physical act like going out to the middle of the street. Activism means, I have a vision for the kind of world that I want, and that vision has to do with compassion and justice and I’m willing to take action toward that goal. That’s how I see an activist. I don’t agree with what everyone who’s an activist is doing. But that’s what I see as activism. To me, “activism” implies working for something beyond your own self-interest, even if your goals benefit you as well. Oppression happens to people in their bodies, and all these complicated issues that we’re dealing with as activists are affecting people in their lives and in their bodies. When someone is suffering because someone else is using power to control them without their consent, that’s what oppression is to me.

My relationship to activist communities has been strengthened by my understanding of “inter being”. Thich Nhat Hahn tells the story of the Rodney King beating to explain this concept:

We all saw the video of the Los Angeles policemen beating Rodney King. When I saw these images, I identified with Rodney King, and I suffered a lot. You must have felt the same. We were all beaten at the same time. But when I looked more deeply, I saw that I am also the five policemen. I could not separate myself from the men who did the beating. They were manifesting the hatred and violence that pervades our society (Hahn,

Peace is Every Step, 1992).

It’s not just that you’re a microcosm but you are the universe, you are the world, you are the society. Each individual has the possibility to be in touch with all of the elements in society. As a poor person, I was forced to understand not only my reality but also the reality of rich people. At the same time a rich person could choose to realize that they are also in touch with the realities of poor people because they could not exist without us. They are dialectically linked and what that means in terms of inter being is that they inter-are. They cannot exist without each other. But we can all work towards creating the conditions where there is no wealth or poverty. Growing up in an oppressive society damages every single person in that society. We can change the structures, but if we do not change ourselves through healing, the structures will become oppressive in another way. We must learn to communicate with each other honestly and respectfully. Emotional and spiritual healing is part of resistance work.

Healing from the extreme violence from my childhood has not only politicized me, but has cemented my commitment to revolutionary social change.

Mumia Abu Jamal writes that

the system is not a true reality, but an idea which can be fought and dismantled. People forget that we don’t need the system, or the accessories we mistakenly assume are essential for living. We need only the things God gave us: love, family, nature. We must transform the system. That’s the challenge (Abu-Jamal, 76).

I am not willing to live in a society that tolerates child abuse. I am not willing to accept the system that exists in the united states just because it is here. I do not believe that I have to exploit others to survive. This society is rotten to the core. From the beginning, the united states has foundationally relied on violence to establish itself. Understanding and articulating this, and the ways it has affected my personal and the social present, has given me the space to envision alternatives, to realize that there is always a choice. I want to live in a society based on the values that are important to me; communalism, respect and love. This is what I mean by revolution.

The united states is a settler colonial state, whose foundations rest on slave labor and genocide. It was built on top of indigenous nations that were already living here. European settlers used the excuse of manifest destiny, a “god-given decree”, to justify the horrible, violent tactics that created a thriving nation-state on this land mass. Christianity, a religion whose roots are deep in the soil of the Middle-East and Africa, has been used on every continent of the earth- including Europe- as a European tool for subjugating indigenous people.

I don’t believe that many non-native “americans” have taken the time or energy to get connected to what that really means, not just intellectually, but on an emotional & spiritual level. I know that it is difficult. Often when I do this I immediately want to move towards the important work of finding solutions, possible ways to reduce the damage that’s been done. I want to support those who are working to preserve what’s left of indigenous ways of being that haven’t been destroyed. It hurts too much to stay with the knowledge of my culpability in genocide, to keep the knowledge in my heart.

We as a nation have become numb to the pain and suffering that is our legacy. How has this numbing occurred?

Christianity, a faith based inherently on the concept of universal love and non-judgementalness, has been distorted in the mainstream to create a shame-based culture, motivated by fear of vengeful judgement. In the overculture’s (i.e. dominant culture) version of christianity, there are only saints and sinners. In a culture where we are taught that we have to exploit others to survive, we are in a catch-22. Many people choose to live lives of denial to the ways we perpetuate others suffering in order to place ourselves in the seat of the righteous judge, presiding over the failures and shortcomings of everyone but ourselves. Even people in consciousness-raising activist communities fall to the task of judging and blaming people in their own communities — creating shame-based counter-cultures on platitudes of hierarchical moralistic thinking.

The education system in this country was brought to us from a general in Napoleon’s army. He was working hard to develop and distribute a system that would train average french people to be good obedient soldiers. The first students of these schools were forced to class at bayonet point. The school system was opposed to ideas of critical thinking and self-directed studies toward liberation and autonomy. It was a school system that used bells, grades, levels of punishment, and memorization techniques to teach people how to listen to orders and carry them out exactly as their instructor dictated. This system is a form of mass mind control. This is the system we have in most of our public and private schools today (Gatto, 1992).

I view the education system as a form of long-term state-sanctioned emotional abuse. Students who do not work well within the current model are routinely humiliated and berated by teachers and students alike. The version of history that is taught in most schools is the Master Narrative, the rich white christian success story. 99% of it has nothing to do with reality, and it has very little relevance to the communities of those supposedly being taught their history. Critical thinking is discouraged and now it has reached such an extreme that in order to move forward towards graduation, students will have to vomit out these Master Narratives in the form of standardized tests year after year. This nation is attempting to turn multidimensional human beings into gingerbread cookie cut outs, flattening our spirits in the process.

When facilitating a 12-course challenging racism workshop, I ask participants to look into where they’ve felt disempowered as children. I encourage people to think of the ways that these lessons of disempowerment aid them in learning to take power over others in their lives. Many participants come to the discussion with very personal stories of the ways that they have been disempowered, including examples of various forms of oppression, forced conformity, losing their language or parts of their ancestral histories, and child abuse in all forms.

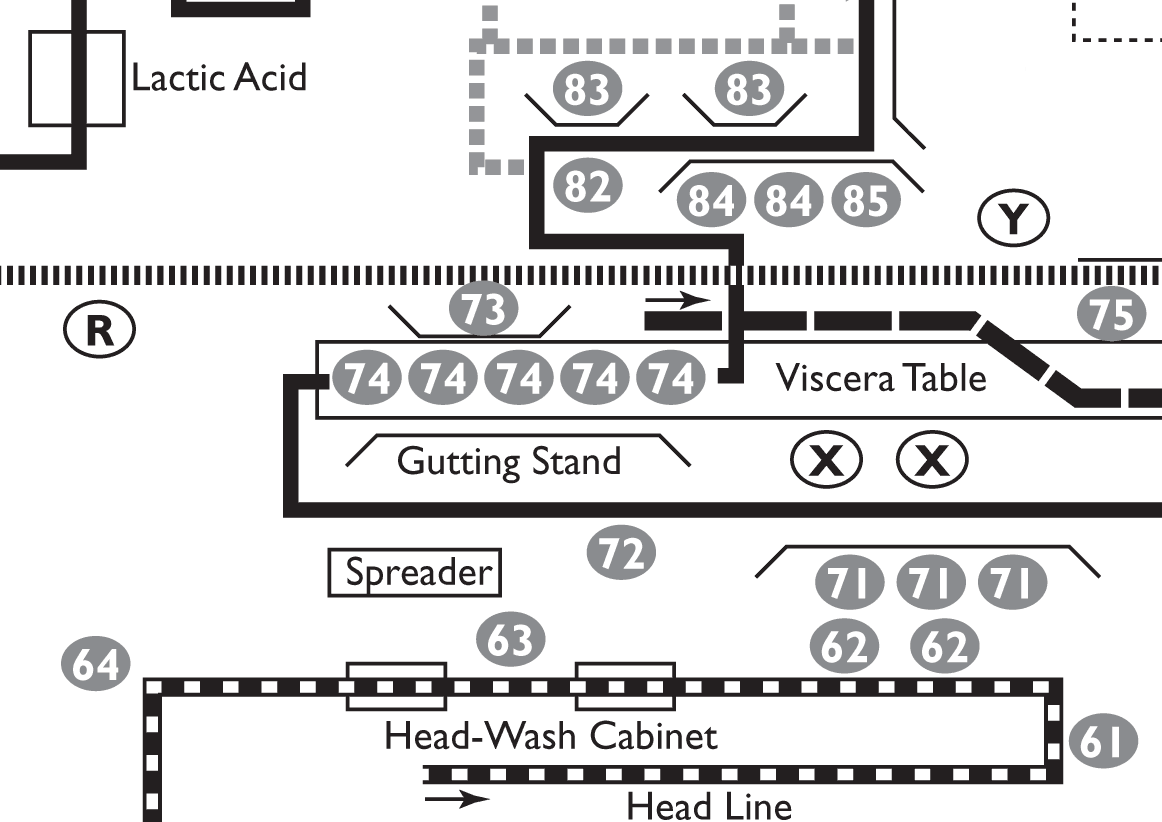

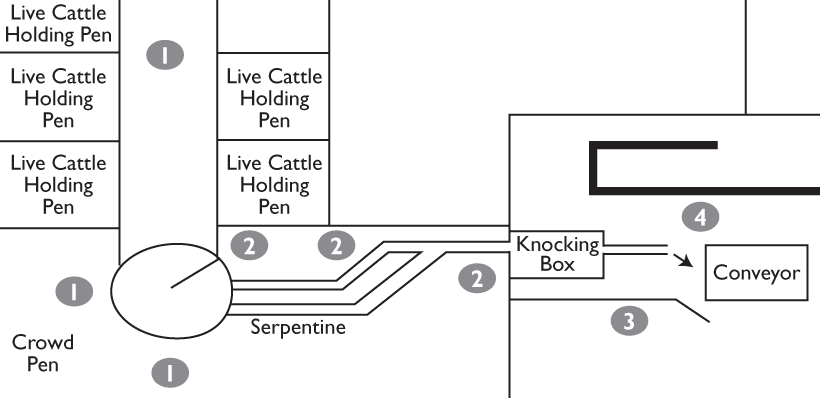

The overculture in the US does not encourage children, or anyone, to take charge of our own survival. Why don’t we learn in school to grow food; build a house or even a fire; compost; build a solar panel; make cloth and sew; or skin, dress and cook an animal? Instead, we are taught skills that will only benefit us if we are dependent on the oppressive system as it presently exists. We are taught that the only way to survive under our current econmic system is to buy product. Food, clothing, housing, entertainment, health care and even our way into each other’s hearts are all relegated to the amount of money you can put down. Concurrently, our dreams become assigned to how much money we can make. Freedom of being becomes intertangled with economic progress — whereas economic freedom becomes the idea of how to obtain true liberation.

Society operates within the economic philosophy of social darwinism (i.e. survival of the fittest). Capitalism pits one person against another in the constant struggle for our basic necessities. Through the institutionalization of racism, colonialism, sexism and other systems of domination, oppressed people are put in a position of enforced weakness. Simultaneously, on an emotional level we are given the message that our survival depends on the acceptance of the same values that keep us in an inferior position in society. For many of us, it is too painful to continue to function while holding the knowledge that we are participating in a society that is hurting us and others. Our self concepts are damaged from the get go by the oppressive system and the messages about who we are as individuals and in society.

We are force-fed outright lies about who we are and who’s histories define our identity as a nation. Henry Kissinger wrote that “history is the memory of states.” Mainstream versions of reality mystify and obscure people’s real stories, relegating them to paranoid fantasies of the disenfranchised and “weak” members of society.

hero conquerors

empty lands

ignorant savages

hysterical women

inferior races

is it any wonder

that they are saying

there are

false memories

now?-f. spavarious

Is it any wonder that a nation who can commit atrocities against “others” eats it’s young?

I am a survivor of child sexual abuse, and I work to educate people about the effects of child abuse in order to end it. I also work on confronting oppression in all it’s forms. Disconnected thinking would make me struggle with how to bring these issues together, but the connections are glaringly obvious. The brutality that manifests itself within my culture as child abuse is the same brutality that manifests itself as “government policy”, exploitation, expansionism and imperialism.

The fact that a person can learn about forced relocation of traditional Dineh (Navajo) people at Big Mountain in Arizona and feel numb or powerless to do anything about it is a direct result of the numbing required to function in an oppressive society.Simultaneously, when a person witnesses the pain and anguish experienced by child and adult survivors of ritual abuse, yet continues to adopt the attitude of a skeptic, or even worse, buys into the propaganda of the false memory foundation, it is the same numbing process occurring. We are not only brought up to believe that we do not deserve to have power or control over our own destinies (except a select few who hold the fate of the world in their hands), but “we have also bought into a set of ideas about the nature of the world that makes us believe that nothing fundamental really can be changed” (Lerner, 52). Each individual is completely powerful. Each person is a living manifestation of what some people choose to call god, who to me is Love, the life force that makes everything move. In order to transform society, we must transform our own deeply held beliefs about the nature of society and ourselves. As Thich Nhat Hanh says: “Peace work is not a means. Each step we make should be peace. Each step we make should be joy. Each step we make should be happiness. If we are determined, we can do it” (Hahn,

peace is every step 42).

And as someone very wise said: “We are all Mother Earth and we must heal ourselves”.

It is in making these connections that we will no longer be able to separate ourselves from our actions, from our commitments against oppression, and from the Earth Herself. My own healing must be an integral part of my work to heal the rest of the world.