http://www.dangerousminds.net/comments/ ... s_of_20014

Moderators: Elvis, DrVolin, Jeff

Room 237

Production year: 2012

Country: USA

Runtime: 102 mins

Directors: Rodney Ascher

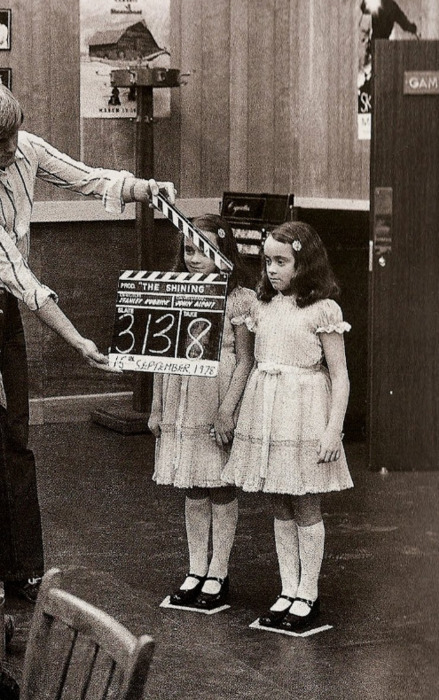

ROOM 237 is a subjective documentary feature which explores numerous theories about Stanley Kubrick’s “The Shining” and its hidden meanings. This guided tour through the most compelling attempts to decode this endlessly fascinating film will draw the audience into a new maze, one with endless detours and dead ends, many ways in, but no way out. Discover why many have been trapped in the Overlook for 30 years.

http://room237movie.com/the-film/

In this uncut conversation from The Kubrick Series - the Movie Geeks United exploration of the films of Stanley Kubrick - director Rodney Ascher and producer Tim Kirk discuss the various theories related to The Shining as detailed in their documentary Room 237. This interview was conducted at the early stages of production on their documentary, which would later premiere at Sundance, Cannes, and has been picked up for release by IFC Films.

Magic circle’ in Scotland is a description that some Scottish citizens (they) assert applies to a collective ring of purported establishment individuals who have engaged in sexual deviations, homosexual practices and paedophilia.

Twinned with this assertion, there is an overall contention by these same Scottish citizens that there was/is a conspiracy by these purported establishment figures that in order to foster and further their deprived ends they pervert the course of justice.

In Scotland the level of accusations rose to a fever pitch in the late eighties early nineties. Thus Lord Nimmo Smith was commissioned as a joint author of the Report on an Inquiry into an Allegation of a Conspiracy to Pervert the Course of Justice in Scotland (1993).

A notable casualty of ‘Magic Circle’ accusations was Lord Dervaird, other suspected judges such as Lord Weir avoided public opprobrium.

Lord Nimmo Smith’s 1993 report was in part withheld from public scrutiny.

....

Bruce Dazzling wrote:A bit tedious, but interesting.In this uncut conversation from The Kubrick Series - the Movie Geeks United exploration of the films of Stanley Kubrick - director Rodney Ascher and producer Tim Kirk discuss the various theories related to The Shining as detailed in their documentary Room 237. This interview was conducted at the early stages of production on their documentary, which would later premiere at Sundance, Cannes, and has been picked up for release by IFC Films.

http://www.openculture.com/2012/06/rare ... rkeri.html

Rare 1960s Audio: Stanley Kubrick’s Big Interview with The New Yorker

in Film | June 8th, 2012 4 Comments

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=pl ... gDQ&t=2405

Stanley Kubrick didn’t like giving long interviews, but he loved playing chess. So when the physicist and writer Jeremy Bernstein paid him a visit to gather material for a piece for The New Yorker about a new film project he was writing with Arthur C. Clarke, Kubrick was intrigued to learn that Bernstein was a fairly serious chess player. After Bernstein’s brief article on Kubrick and Clarke, “Beyond the Stars,” appeared in the magazine’s “Talk of the Town” section in April of 1965, Bernstein proposed doing a full-length New Yorker profile on the filmmaker and his new project. For some reason, Kubrick accepted. So later that year Bernstein flew to England, where Kubrick was getting ready to film 2001: A Space Odyssey. Bernstein stayed there for much of the filming, playing chess with Kubrick every day between takes. When the piece eventually ran in The New Yorker it was appropriately titled “How About a Little Game?”

One thing Bernstein learned about Kubrick was that he loved gadgets. He had a special fondness for tape recorders. In the profile, Bernstein quotes the filmmaker’s wife Christiane as saying, “Stanley would be happy with eight tape recorders and one pair of pants.” So when it came time to do the interviews, Kubrick took control as director and insisted on using one of the devices. “My interviews were done before tape recorders were commonplace,” Bernstein later wrote. “I certainly didn’t have one. Kubrick did. He did all his script writing by talking into it. He said that we should use it for the interviews. Later on, when I used a quote from the tape he didn’t like, he said, ‘I know it’s on the tape, but I will deny saying it anyway.’”

Kubrick talked with Bernstein on a range of topics related to his early career. In the nearly 77 minutes of audio preserved in the recording above, Kubrick discusses his bad grades in high school and his good luck in landing a job as a photographer for Look magazine, his earliest film work producing newsreels, and all of his feature films up to that point, including Paths of Glory, Lolita and Dr. Strangelove. He talks about his working relationships with Clarke and Vladimir Nabokov, and his views on space exploration and the threat of nuclear war.

The exact time of the interview is difficult to pin down. Sources across the Internet give the date as November 27, 1966, but that is certainly incorrect. While it’s true that Kubrick gives the date as November 27 at the beginning of the tape, Bernstein’s profile–which includes material from the interview–was published on November 12, 1966, and Kubrick made corrections to the galley proofs as early as April, 1966. The interview was apparently conducted in multiple takes starting on November 27, 1965 and ending sometime in early 1966. Filming of 2001: A Space Odyssey commenced on December 29, 1965 (a month after the taped conversation begins), and near the end of the tape Kubrick mentions having already shot 80,000 feet, or about 14.8 hours, of film.

Where the Rainbow Ends: Stanley Kubrick's Eyes Wide Shut (Part 1).

A Few Years in the Absolute Elsewhere

Tuesday, September 3, 2013

.....only those who look for a meaning will find it. Dreaming and waking, truth and lie mingle. Security exists nowhere. We know nothing of others, nothing of ourselves. We always play. Wise is the man who knows.

Arthur Schnitzler, Paracelsus.

'I've forgotten it,' replied Fridolin with a vacant smile, feeling totally at ease.

'That's unfortunate,' said the gentleman in yellow, 'for it makes no difference here whether you've forgotten the password, or whether you never knew it.'

Arthur Schnitzler, Dream Story.

When Eyes Wide Shut was released in the summer of 1999, the overwhelming critical reaction was one of respect for its recently departed director, and muted disappointment with the movie itself. Trading on the popular image on Kubrick as a monastic (or perhaps autistic) recluse, the consensus was that Eyes Wide Shut was sterile and painfully out of touch with the sexual mores of the 20th century's twilight years. It was, or so the wisdom went, a relic mined from the splendid isolation of its feted creator, as divorced from the social and cinematic currents of 1999 as its soundstage "New York" was from the real thing. This all sounded persuasive enough to me that I didn't watch the thing until a few years later. My expectations remained extremely measured, but I'd somehow or other acquired a vague suspicion that maybe the critics had been all wrong about Kubrick's swansong.

That suspicion became a certainty almost immediately: EWS dazzled and engrossed me from the first frame. It felt like such a different beast from the movie so many critics had either savaged or politely dismissed - Andrew Sarris called it "turgid", David Denby "pompous", and Louis Menand in the New York Review of Books claimed that "nothing" worked in it - that I was actually stunned by what I was seeing. EWS was shot through with many instantly recognizable staples of Kubrick's formal mastery - the smooth, sinuous Steadicam tracking, the utilization of natural light sources - and yet at the same time it felt different from anything the director had attempted before. Though possessed of a grand visual imagination and world-building sensibility (as evidenced, for example, by A Clockwork Orange), Eyes Wide Shut was Kubrick's first complete foray into surrealism and the cinema of dreams. It was almost his "Lynch" movie - playing like a collision between Lynch's psychosexual dream landscapes and Kubrick's more clinically precise formalism and intellect. (The presence of Chris Isaak on the score, though apparently a serendipitous discovery on the set, feels like a direct nod to Lynch. In the picture above, Cruise looks almost like he could be Dale Cooper lost in the maddening corridors of the Black Lodge.) EWS felt somehow thematically denser and more meticulously thought out than any of his previous features - Kubrick had after all been mulling over Arthur Schnitzler's source novel Traumnovelle (or Dream Story) since 1968, and the shooting of Eyes Wide Shut itself had ballooned into a record-breaking 15 months. The result was the creation of an oneric landscape or labyrinth where every detail is infused with a wider significance and meaning, however initially elusive. I've watched EWS many times since, and my appreciation for its sly complexity and consummate execution has only increased with each viewing. To whatever extent I would stake my shirt on an aesthetic judgement, I would stake it on the contention that EWS is a masterpiece that soared over the heads of its many detractors in the summer of 1999.

If the consensus on EWS has not quite turned since then, the world itself has changed immeasurably. With hindsight, the 90s feels like it was the last oasis of illusionary calm before everything became saturated with anxiety and uncertainty. In the 90s, the Cold War was over, and free market global capitalism appeared robust enough to warrant Francis Fukuyama's famously precipitate declaration of the end of history: "What we may be witnessing is not just the end of the Cold War, or the passing of a particular period of post-war history, but the end of history as such: that is the endpoint of mankind's ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government." After the excesses of the 80s, the burgeoning ethos of political correctness persuaded us that we were after all good, enlightened people: we internalized a morality of correct language and attitudes which could be spun like a gramophone record wherever the occasion required it, and in this manner kept our eyes wide shut from the darker realities of the world we participated in. However, as Sam Capola tells Travolta in Saturday Night Fever: "You can't fuck the future. The future fucks you!" History wasn't over; it was just clearing its throat. The beginning of the 21st century proved the oasis at the end of history to have been a mirage, and the supposed equilibrium of western democracy was subject to a biblical gamut of calamities. But while everything was collapsing around us and the scales were being lifted from our eyes, the ambiguous technology of the internet was slowly rewiring the world's collective neural pathways: the simultaneous slow-collapse of the world-order and rapid growth of the internet precipitated an explosion of conspiranoid folk mythologies. Just as the nature of the world's power-inequalities and injustices became ever more crystal clear and unavoidable, so its projections in the popular imagination became ever more fantastic and unreal.

It is a testament to the mythic aura surrounding Kubrick and his work that no other 20th century director has become quite so thoroughly enshrined in this conspiranoid mythos (or, at any rate, I suspect a google search of Ingmar Bergman illuminati doesn't yield quite so many hits.) Neo-Gnostic Jay Weidner became the most notorious of Kubrick's mythologists by arguing that The Shining was an allegorical confession of the director's involvement in the creation of fake Apollo 11 moon landing footage. If you buy the first premise, I suppose the second is not unreasonable. Inevitably, Eyes Wide Shut has experienced a second lease of life amid the garish internet culture of Illuminati "exposés" and pop occult symbology overload. Believed upon its release to be a baroque fantasia about the difficulties of marital fidelity, EWS was now revealed to be an exposé of the occult rituals and mind control techniques employed by elite secret societies. In particular, the film was associated with perhaps the murkiest back-alley of conspiracy culture: the mythos of the mind-controlled sex slave. This highly lurid strand of conspiracy theory was initiated by one comparatively credible book: The Control of Candy Jones.

I've blogged about this before; in brief, Candy Jones was a Pennsylvania-born model who had been a pin-up during the 2nd World War. In 1972, she married Long John Nebel, America's first paranormal talk radio host. I know, you couldn't make it up. Troubled by mood swings in Candy that almost amounted to a split-personality, Nebel began to hypnotize her, and gradually a very disturbing narrative emerged. According to her recollections under hypnosis, Jones been been subjected to a barrage of hypnosis, experimental drugs, and sexual trauma by shadowy figures associated with the C.I.A., with the result that she developed a surrogate personality which the C.I.A. utilized as an operative. The jury remains out on the plausibility of the Candy Jones narrative - stories like this would make you wonder, though. But it remains eminently credible compared to what was to follow.

By the 90s, the loose-ends of the real MK-ULTRA program had mushroomed into the mythical form of Project Monarch, and the mind-controlled sex slave mythos became incorporated into the whole strange miasma of paranoid millennial fever dreams which also included Bill Cooper's militia manifesto Behold A Pale Horse and the notorious satanic ritual abuse panic. Cathy O'Brien (TranceFormation of America) and after her Brice Taylor made the Monarch sex slavery narrative into a minor cottage industry that stoked the fears (and, one suspects, repressed desires) of the paranoid religious right. The essential formula of these books was to include as much lurid and truly appalling sadistic depravity as might not altogether numb the mind of the reader; and to document the sexual exploitation of the protagonist at the hands of as many prominent politicians and popular entertainers as might not altogether beggar his or her belief. I find it difficult to tell if these women were mentally ill and tragically exploited, or just entrepreneurs of the unspeakable; their material is so mind-bogglingly horrific and depraved that it's hard to know whether to laugh or cry. (Check out, for example, Richard Metzger's DisinfoTV interview with Brice Taylor in which she claims that Sylvester Stallone shot a pornographic film wherein she was forced to have sex with dolphins. Now that you really couldn't make up.) A major component in the attraction of this peculiar mythos lies in the control cues and triggering devices which are supposedly utilized to manipulate Monarch victims. The Manchurian candidate of the novel and John Frankenheimer movie had the Queen of Hearts suit; Mark Chapman, if you believe the lore, had The Catcher in the Rye. The Monarch Project, on the other hand, tended toward children's fantasy novels with female heroines, most notably L Frank Baum's uncannily archetypal Oz novels. Conspiranoid critics of EWS reason that this is the source of the movie's prominent and mysterious rainbow motif. But was it really plausible that Kubrick, chipping away at his decade-spanning ambition to adapt Traumnovelle, was tuned into this low-grade tabloid conspiracism?

On the other hand, I'm not entirely sure that the conspiranoids got EWS completely wrong. The film is, after-all, certainly about sexual slavery and exploitation of some kind, and it does feature a ritualistic sex orgy which Kubrick associates with the powerful echelons of society to a much greater degree than Arthur Schnitzler did in the source novella. Ironically, just as the reception of EWS was drifting into the realm of fantasy and folk-lore, many of the film's themes (which were deemed largely insignificant on its first release) began to percolate into the nightly news. The sybaritic and predatory orgies of Silvio Berlusconi and Dominique Strauss-Kahn, combined with the unnerving sense of a very rotten and corrupt British establishment implied by the Grand Guignol of post-mortem Jimmy Savile revelations, have lead us to rediscover a feeling of unease about the sexual license and immunity from prosecution of our elites. Part of the reason why our perception of EWS is gradually shifting is that our vision of the world has become more acute since then. In the more optimistic and carefree years of the 90s, who but radicals and conspiracy-theorists dwelled overlong on the notion that society was largely under the thumb of a neo-feudal over-class which runs rampant and gets away, often literally, with murder? Nowadays, who doesn't? Even back in 2000, cartoonist and essayist Tim Kreider wrote a brilliant analysis of EWS (Introducing Sociology: A Review of Eyes Wide Shut) which argued the film's primary theme was not the difficulties of marital monogamy, but rather the fundamental and ingrained corruption of a society enthralled by the wealth, power, and conspicuous consumption of its elites: "The real pornography in this film is in its lingering depiction of the shameless, naked wealth of millennial Manhattan, and of its obscene effects on society and the human soul. National reviewers' myopic preoccupation on sex, and the shallow psychologies of the films central couple, the Harfords, at the expense of every other element of the film - the trappings of stupendous wealth, its references to fin-de-siecle Europe and other imperial periods, its Christmastime setting, even the sum Dr Harford spends on a single night out - says more about the blindness of the elites to their surroundings than it does about Kubrick's inadequacies as a pornographer. For those with their eyes open, there are plenty of money shots." So, in a sense, if Kreider is right, EWS is a kind of conspiracy movie, in so far as it essays the real theme of cogent, intelligent conspiracy theory: the corrupt and corrupting nature of how power is exercised in our world. But was Kreider's analysis right?

Over the years then, two separate ways of viewing Eyes Wide Shut have emerged. The most immediately obvious, and still the most common, is to regard it as a basically humanistic study of the tensions between sexual fantasies and reality, and between monogamous intimacy and sexual license and libertinism. According to this way of viewing the film, the conspiracy thriller elements are really only a projection of the sense of danger associated with unfettered sexuality, and of Bill Harford's specific anxieties regarding his wife's fidelity and its threats upon his own masculinity. As the whole film may be viewed as a kind of dream quest for Harford's character, then these elements can be regarded as pointing to psychological rather than literal aspects of reality. The drama of the sacrifice at the orgy can be viewed as the charade which Ziegler insists that it was. The ending is happy: having lost themselves to find themselves in their real and dreamed adventures, Bill and Alice are reunited, a little older and wiser, a little more honest with themselves and better equipped to deal with the difficulties of married life and the long haul of monogamous commitment. This was, more or less, the movie I saw the first couple of times I watched EWS. The third time, however, was a very different experience. The background and foreground seemed to shift places; elements whose importance I'd minimized in the previous viewings became the most significant this time around. Although I hadn't read Introducing Sociology at that point, I saw the movie very much as Kreider had. I was struck by how many details I'd failed to notice, even though they were staring me in the face. I suspect that Kubrick deliberately and ingeniously constructed Eyes Wide Shut to resemble that specific type of optical illusion which plays on how we organize and structure perceptual information. I selected the above example (probably the best known) because I have a very vivid recollection of finding the emergence of the old crone image a rather sinister and uncanny effect when I first saw it as a child; it then occurred to me that it was an apt enough choice, considering that notorious sequence in The Shining which nobody has ever been able to forget. Eyes Wide Shut embodies this kind of perceptual ambiguity, this sense of a different picture emerging from the same image depending on how you look at it, through and through, even down to its title. On the one hand, in an obvious sense Eyes Wide Shut refers to the initial naivete of the Harford's regarding their sexual fantasies and complex feeling towards another; viewed another way, however, it can refer to the ways in which we function in a corrupt society by shutting our eyes to the aspects of it which we find unpalatable and lack the courage to confront. At an even more sly level, it might refer to how we can watch the movie and think we know what the title means, without seeing a damn thing. We diagnose the blindspots of the Harford's, but miss our own.

Continued shortly.

Harvey » Fri Feb 21, 2020 1:49 pm wrote:^ Don't know if you've happened across Ian Watson's entertaining account of his experience with Kubrick: http://www.ianwatson.info/plumbing-stanley-kubrick/

“Do you know what the essence of movie-making is?” Stanley asked me. “It’s buying lots of things.”

Users browsing this forum: No registered users and 1 guest