Frontiers in Sociology: Is society caught up in a Death Spiral? Modeling societal demise and its reversalMichaéla C. Schippers , John P. A. Ioannidis, and Matthias W. J. Luijks

...

Using the metaphor of a corporate heart attack, Fitzgerald discerns a hidden, subtle and overt phase of decline (Fitzgerald, 2005). In the hidden phase, denial or willful blindness often prohibits management from taking (the right) actions. Against their better judgment, they hope if they ignore it, the market will not notice. In that phase, on average a third of a company’s competitive value is lost. If a new market challenge presents itself, the company is often unable to face the challenge. In the subtle phase, the decline becomes more obvious for those who are observant and know where and how to look and how to interpret what they see. By the end of this phase, often a full two-thirds of the company’s competitive value is lost. Unfortunately, many companies only start to admit and address the problem in the overt phase. By that time, the problems are so big and ingrained, that addressing them has become extremely difficult. While many managers do watch the company’s financials, they often fail to address other metrics such as market-share trends, customer turnover and staff satisfaction. Often these drivers are the earliest predictors of corporate performance. Important blockers of performance are distrust, bureaucracy and low performance expectations, while drivers are decisiveness, accountability and acknowledgement of work. It is key to identify and quantify early warning signals, e.g., an excess of staff, especially managers, a decrease in lower-level workers, tolerance of incompetence, and lack of clear goals (Lorange and Nelson, 1985). Reversing organizational decline starts with the realization and recognition that the organization is in decline. These danger signals should then be aligned with a concrete plan to change. A dialog between top-down and bottom-up is needed (Lorange and Nelson, 1985). If the company is able to take those steps, follow-up monitoring is needed to make sure the changes that are proposed and made are effective (Lorange and Nelson, 1985). While in the early phases underreaction may be the problem, in later phases, the danger comes from overreaction (cf. Lai and Sudarsanam, 1997; Hafsi and Baba, 2022).

We believe that similar processes may happen at the societal level. Recent examples of societal systemic shocks are 9/11, the 2008 global financial crisis and the COVID-19 crisis (Centeno et al., 2022). On a societal level, researchers studying policy success and failure have started to investigate the role of policy under- and over-reactions (Maor, 2012, 2020). Policy overreactions are “policies that impose objective and/or perceived social costs without producing offsetting objective and/or perceived benefits.” (Maor, 2012; p. 235). For instance, preemptive overreaction is a form of policy that will often rely on persuasion by presenting “facts” in a certain way, manufacturing a perceived threat, and using messages to swing the public mood (Maor, 2012). An example is the cull of all pigs in Egypt during the swine flu crisis in 2009, even though zero cases had been reported (Maor, 2012). An important explanation is that in such cases groupthink may play a role. Groupthink, the forced conformity to group values and ethics, has symptoms such as collective rationalization, belief in inherent morality, stereotyped views of outgroups, pressure on dissenters, and self-appointed mind guards (Janis, 1972, 1982a,b; Janis et al., 1978). Preemptive overreaction shows that one is taking forceful and decisive action against a perceived threat, that may never materialize, and motives could be political and/or monetary gain (Maor, 2012).

While the period before the COVID-19 crisis may have been characterized by relative policy underreaction to complex social problems, also referred to as “wicked problems,” such as hunger and poverty (Head, 2018; Head B.W. 2022),

the current times may be characterized by overreaction to certain problems. The COVID-19 crisis seemed to be characterized by groupthink and escalation of commitment to one course of action, at the expense of other possible solutions (Joffe, 2021; Schippers and Rus, 2021). Initial low-quality decision-making was followed by decisions that made things worse (Joffe, 2021; Schippers and Rus, 2021). The sheer scale and severe disruption caused by these policies has increased inequalities (Schippers, 2020; Schippers et al., 2022), an important marker of societal decline (Motesharrei et al., 2014)...

The process of societal decline is complex and may include social-ecological traps, or a mismatch between the responses of people and the social and ecological conditions they face, e.g., depletion of natural resources (Boonstra and De Boer, 2013; Boonstra et al., 2016). For the current review, we feel that

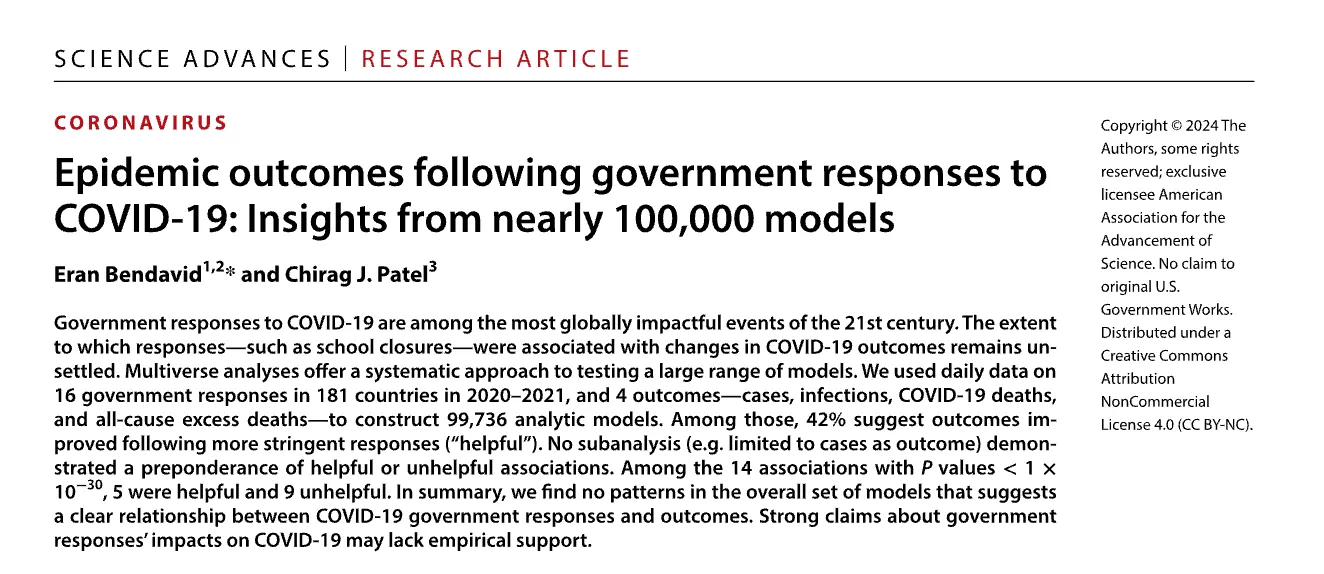

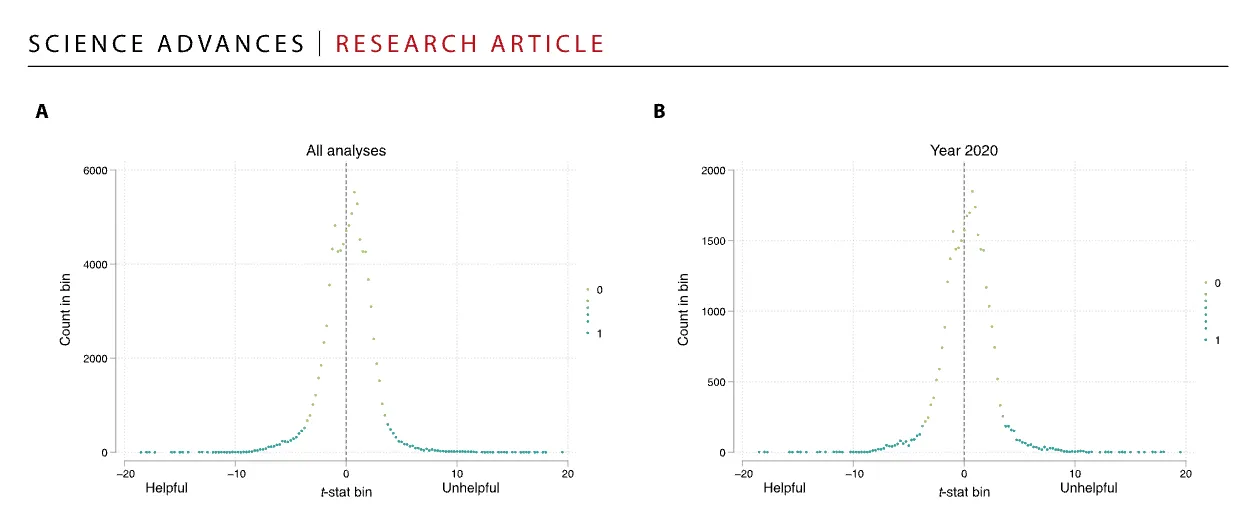

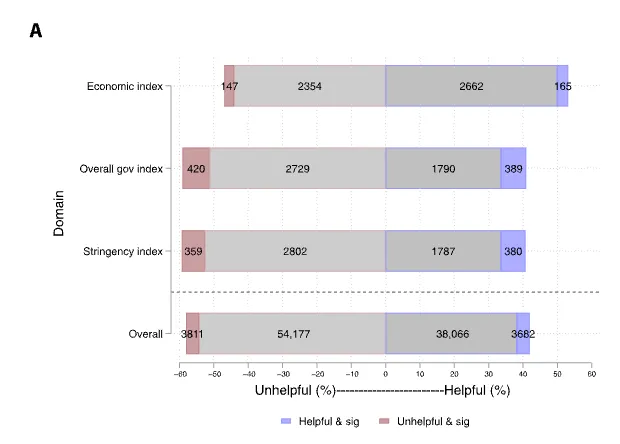

the handling of the COVID-19 crisis may have been an example of overreaction making use of non-pharmaceutical interventions that accelerated existing societal problems, such as inequalities (Schippers, 2020; Schippers et al., 2022). Most countries opted for very similar solutions, with forced lockdowns and aggressive restrictions. Countries that chose a different course of action were highly criticized (Tegnell, 2021). Many countries eventually faced excess mortality rates that were highly unequal across groups, exacerbating preexisting inequalities (Alsan et al., 2021; Schippers et al., 2022). Over-reaction was fueled by (unreliable) metrics (Schippers and Rus, 2021; Ioannidis et al., 2022) and groupthink, resulting in irrational or dysfunctional decision making (Joffe, 2021; Hafsi and Baba, 2022). Furthermore, emotions during crises tend to run high, escalating the risk of harmful overreaction both by policy makers and the general public (Sunstein and Zeckhauser, 2010). Governments may suffer from an action bias, a tendency to take action whether it is needed or not, including excessive actions (Patt and Zeckhauser, 2000) despite information that the policies may do more harm than good (for reviews see Joffe and Redman, 2021, Schippers and Rus, 2021; Schippers et al., 2022). Unnecessary crisis response as a form of policy overreaction may sometimes occur as a way to shape voters perceptions of a decisive and active government (Maor, 2020). Excessive action and exercise of control over societal structures, e.g., public health, may enhance centralization of power and decision-making, and authoritarianism (Berberoglu, 2020; Desmet, 2022; Schippers et al., 2022; Simandan et al., 2023).

When governments make use of mass media to spread negative information, a self-reinforcing cycle of nocebo effects, “mass hysteria” and policy errors can ensue (Bagus et al., 2021). This effect is exacerbated when the information comes from authoritative sources, the media are politicized, social networks make the information omnipresent (Bagus et al., 2021), and dissenting voices are silenced (Schippers et al., 2022; Shir-Raz et al., 2022). This may lead to a vicious cycle of ineffective dealing with crises, low-quality decision-making and dysfunctional behavior, intensifying the current crises and leading to new ones, and eventually societal decline and even collapse....

At the same time decline in organizations was often triggered by the COVID-19 crisis and non-pharmaceutical interventions implemented to reduce viral spread, such as closing of restaurants and “non -essential” shops (Brodeur et al., 2021). As early as April 2020 in the United States, the number of active business owners decreased by 22% within just 3 months (Fairlie, 2020; Brodeur et al., 2021). Taken together with other effects such as rising inequalities, increase in immigration, changed labor market, damaged mental health and well-being, this is arguably a big shock to societal cohesion (Silveira et al., 2022), increasing state fragility and decreasing state legitimacy (Seyoum, 2020).

Repeated low-quality decision-making...

In the COVID-19 and accompanying economic crisis for instance, there is evidence of such an action bias (Winsberg et al., 2020; Magness and Earle, 2021, p. 512; Schippers et al., 2022).

People often assume that a big problem needs harsh and drastic solutions, while less drastic, but precise solutions, as well as targeted, evidence-based interventions can work better than aggressive solutions (cf. Brown and Detterman, 1987; Wilson, 2011; Walton, 2014). Action bias, along with escalation of commitment and sunk cost fallacy may have played a role in the suboptimal decision-making processes surrounding the COVID-19 crisis (Schippers and Rus, 2021). Combined with the (in hindsight) overestimation made by experts of the expected infection fatality and of the buffering effects of several aggressive measures (Chin et al., 2021; Ioannidis et al., 2022; Pezzullo et al., 2023) led to a disastrous chain of self-perpetuating decision-making. (Magness and Earle, 2021; Murphy, 2021). Instead of dialing back, the general political climate and response doubled down on the measures and on defending a narrative in their support, leading to a Death Spiral of low-quality decision making and serious consequences.COVID-19 crisis and rising inequalitiesIn the context of the COVID-19 crisis, some have stated that this is a great leveler and that “we are all in this together,” however, this is clearly not the case: vulnerable groups have been unevenly negatively impacted (Ali et al., 2020). Inequalities have risen steeply since 2020 (Schippers et al., 2022). While this trend was already visible before the pandemic started (for a review see Neckerman and Torche, 2007), especially

billionaire wealth increased dramatically early during the crisis (Schippers et al., 2022; Inequality, 2023). Between March 18, 2020, and October 15, 2021, billionaires’ total wealth increased over 70%, from 2.947 trillion to 5.019 trillion, and the richest five saw an increase in 123 percent. Since then, gains have decreased modestly, because of market losses (Collins, 2022).

Corporate profits also spiked as giant corporations used the excuse of crisis-related supply chain bottlenecks to drive up the prices of gasoline, food, and other essentials (Inequality, 2023). While CEO pay increased, general worker pay lagged behind, increasing the CEO-worker pay gap in the United States (Inequality, 2023). To prove this in 2019 average CEO pay was $12,074,288 per annum compared to a median worker yearly pay at the 100 largest low wage employers of $30,416 in the United States; in 2020 yearly average CEO pay was 13,936,558 (a 15.42% increase) for workers it was 30,474 (a meager 0.19% increase; Inequality, 2023)In effect, global billionaires made 3.9 trillion dollars by the end of 2020, while global workers earnings fell by 3.7 trillion, as millions lost their jobs around the world (International Labour Organization, 2020; Berkhout et al., 2021; p. 12).

The lowest-income workers were hit the hardest. In total, it has been estimated that during the crisis, by 2021, 150 million people were driven into extreme poverty (Howton, 2020). With widespread continuing demise, even the rich may start to lose.

The crisis has worsened many other aspects of inequality, such as educational, racial, gender, and health inequalities (Byttebier, 2022; for a review see Schippers et al., 2022). Nevertheless, the elite may continue to centralize power and make decisions that are not in the interest of most people (Desmet, 2022). As the “masses” end up being in a downward spiral of dwindling incomes, not being able to pay for essentials, such as food, gas, and medicine, they may experience significant financial barriers and may avoid health care in order to save on costs (Weinick et al., 2005), leading to worsening health status for millions (Schippers et al., 2022). Socio-economic determinants of health are often the result of persistent structural and socio-economical inequalities, exacerbated by the COVID-19 crisis (Ali et al., 2020; Schippers, 2020). The term syndemic describes “a set of closely related and mutually reinforcing health problems that significantly affect the overall health status of a population, against the background of a perpetual pattern of deleterious socio-economic conditions” (Bambra et al., 2020; Byttebier, 2022, p. 1036). Prior pandemic crises such as the Spanish flu and other economic shocks led to an increase in inequalities and unequal health and wealth outcomes (Bambra et al., 2020). Sudden economic shocks, such as the collapse of communism, are related to an increase in morbidity, mental health decline, suicide, increased ill health and deaths from substance use (Bambra et al., 2020). These effects were experienced unequally in poorer regions, and among low-skilled workers, exacerbating health inequalities (Bambra et al., 2020). Interestingly, after the 2008 financial crisis, countries that chose not to cut back on health and social protection budgets, had better outcomes than countries that made austere cuts in those budgets (Stuckler and Basu, 2013; Bambra et al., 2020). In current times, people lower on the social ladder bore the brunt of the negative side effects of the measures, in health, lifestyle changes as well as decrease in income (Schippers et al., 2022), even increasing their vulnerability to viral diseases (Enichen et al., 2022).

The dysfunctional situation in most countries worldwide strengthens the incentives for mass migration into Western countries that still offer better prospects, in theory at least. However, this challenge, if mishandled, may lead to importing poverty (Martin, 2009; Murray, 2017) creating an underclass, and further proclivity of an unequal society and possibly a Death Spiral Effect (cf. Gomberg-Muñoz, 2012; Peters and Shin, 2022). Furthermore, there is some evidence that poverty gives rise to higher crime rates (Dong et al., 2020). In the US, even minor crimes are severely punished, and imprisonment of poor people escalates inequalities (Wacquant, 2009; Wilkinson and Pickett, 2009a).

...

Currently, the optimism of connectivity and the internet and the possibilities for open source democracy seem to have faded (Rushkoff, 2003).

Censorship has set in, along with a loss of scientific freedom (Da Silva, 2021; Kaufmann, 2021; Shir-Raz et al., 2022). The scientific debate was stifled during the COVID-19 crisis and dissenting views were censored (Shir-Raz et al., 2022). Suppression tactics resulted in damaging careers of dissenting doctors and scientists regardless of academic or medical status (Shir-Raz et al., 2022). This has led to a loss of trust in science and institutions (Hamilton and Safford, 2021). Worse, when knowledgeable scientists with reasonable arguments and rigorous data are suppressed, this could offer ammunition to conspiracy theorists to claim that orthodox science is non-tolerant and wrong. Especially centralized censorship may increase certainty in radicalized views (Lane et al., 2021). Anyone questioning. science’ and official governmental narratives may be called a conspiracy theorist, as a way of discrediting and delegitimizing critics (Giry and Gürpınar, 2020). It has been argued that conspiracy theories are also a sign of dissatisfaction with governance, society or policies, and some conspiracy theories may turn out to be true (Swami and Furnham, 2014).Surveillance capitalism, the collection and commodification of personal data by corporations, shifts the power of governments toward large companies (Big Other). These corporations have the power to observe and influence human thinking and decision-making for example via direct advertising. Direct advertising has become far more aggressive (Schwartz and Woloshin, 2019), especially for products of little benefit and high sales (DiStefano et al., 2023). Effective direct advertising can be guided by surveillance capitalism. This can be a tool for business (knowing customers preferences) but also an invasion of privacy (Zuboff, 2015, 2023, see also Yeung, 2018).

Worryingly, strategic actors such as large corporations and governments (i.e., the elite) can unevenly influence the media (media bias), possibly leading to an increasingly narrowing of the definition of “facts/true knowledge” versus “fake news/disinformation,” e.g., stating that only governmental or other elite-endorsed narratives represent the. truth’ (cf. Gehlbach and Sonin, 2014). People and scientists that differ in their views from the official narrative, can be censored, marginalized and expelled, even if they are prudent in their publications and wording within the debate (cf. Prasad and Ioannidis, 2022). Some authors have even contended that this combination may bring us on a path toward totalitarianism (Desmet, 2022), and have called for a way to rethink and uphold democracy and democratic principles (Della Porta, 2021; Ioannidis and Schippers, 2022), as well as democratic control of technology (Gould, 1990)....

The COVID-19 crisis and measures of unprecedented severity and duration are related to many negative side effects and increase inequalities worldwide (Marmot and Allen, 2020); hence stress, health, and trauma for vulnerable populations must be addressed (Whitehead and Torossian, 2020). It may take a long time to recover from the economic fall-out and rise in inequalities (Whitehead and Torossian, 2020). Governments should take individual and societal well-being as a spearhead for decision-making in the upcoming years (Frijters et al., 2020). Hopefully, with effective interventions, the tide can be turned and a positive spiral can be induced (e.g., Schippers and Ziegler, 2023). However, while many ideas and proposals may emerge, implementing them without rigorous trials may add further waste after we have already endorsed too many failed interventions.