LilyPat

Moderators: Elvis, DrVolin, Jeff

Nordic wrote:Yeah. Its like celebrating a "Native American Day" by putting on headresses and drinking ourselves sick. Really seems a bit racist to me. But wait, Irish is white, so I guess it can't be "racist" right?

crikkett wrote:Osiris rose on 3/17 too.

The Irish even claim King Tut (apologies to Alice)

http://www.eutimes.net/2010/06/king-tut ... -european/

Irish Classic Is Still a Hit (in Calfskin, Not Paperback)

By EAMON QUINN

Published: May 28, 2007

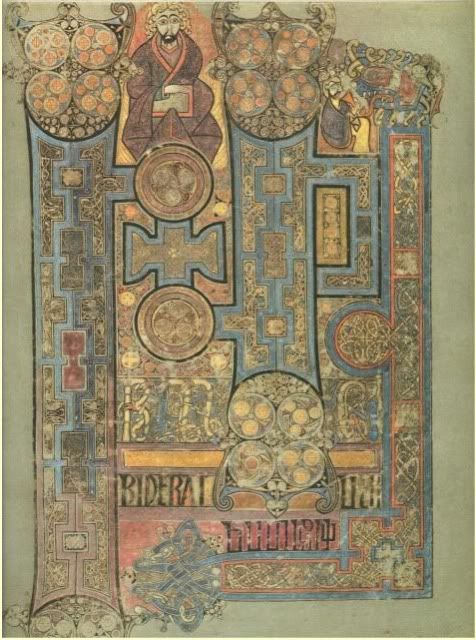

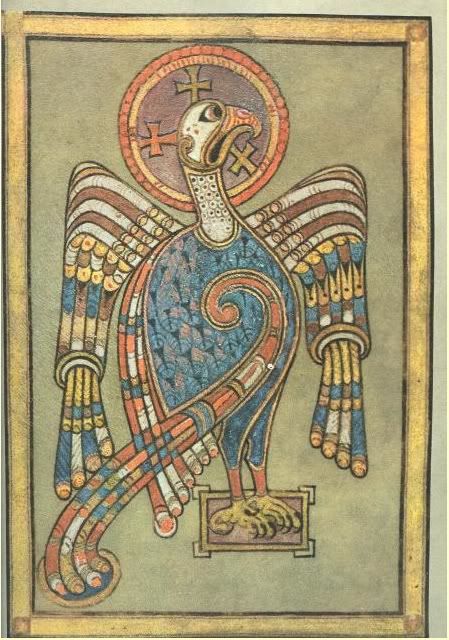

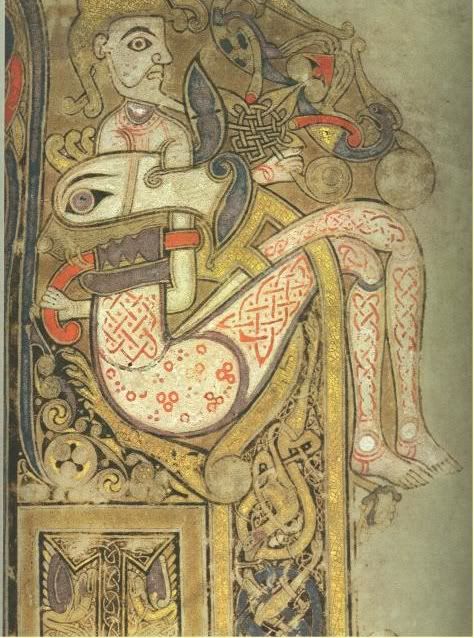

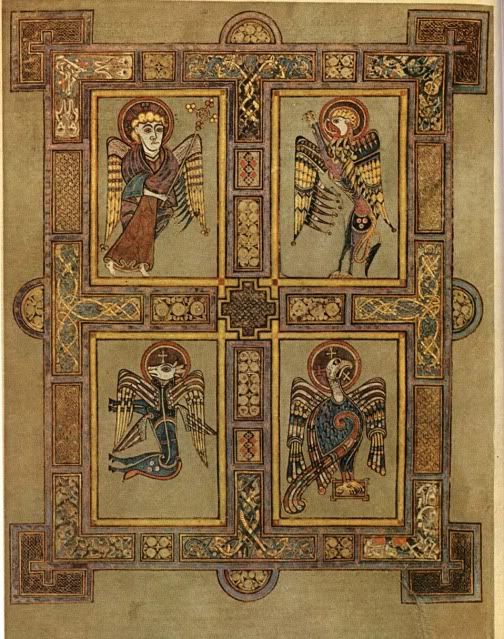

DUBLIN, May 27 — For a manuscript written 1,200 years ago and revered as a wonder of the Western world practically ever since, little is known about the Book of Kells and its splendidly illustrated Gospels in Latin. But the book may be about to surrender a few of its many secrets.

Ross McDonnell for The New York Times

An enlarged image of a page of the Book of Kells at an exhibit at Trinity College in Dublin.

Keystone/Getty Images

The ancient manuscript itself in 1961.

Experts at Trinity College in Dublin, where the Book of Kells has resided for the past 346 years, are allowing a two-year laser analysis of the treasure, which is one of Ireland’s great tourist draws.

The 21st-century laser technology being used, Raman spectroscopy, encourages hopes among those with a romantic view for an ecclesiastical intrigue like “The Da Vinci Code” or “The Name of the Rose.”

But the precise subjects are more mundane. The laser will study the chemicals and composition of the book, its pigments, inks and pages of fine vellum. Experts estimate that 185 calves would have been needed to create the vellum on which the art and scriptures were reproduced.

Pending the laser analysis, experts assume that expensive materials for some of the blue pigments came from the gemstone lapis lazuli, mined in northeast Afghanistan. Yellow pigments are believed to have been made from arsenic sulfide and, bizarrely, reddish Kermes pigments from the dried pregnant bodies of a genus of Mediterranean insect, suggesting extraordinary trade routes for the ninth century.

Some techniques will help to analyze the pigments made from vegetable matter; others will be used to examine the inks.

“A lot of what we have done before has been based on anecdotal reports of the materials that were used,” said Robin Adams, the librarian of Trinity College, who hopes the exacting dot-by-dot analysis by laser will unlock secrets and help his staff preserve the book. “Essentially the laser bounces back, and you get a spectrum. That spectrum tells you whether this pigment is lead, copper or whatever. We haven’t got the reports yet, but we very much expect it to tell us new information about what the monks used.”

Mr. Adams hopes that Trinity’s manuscript research will answer some of his own questions about the book: “I would like to find out whether this work can tell us its relationship with other manuscripts. Is the material used in Kells the same as might be used in England or France? It could tell us a bit about the movement of materials around the monastic houses. We would love to find out how these monastic houses worked as communities, and whether the techniques were the same. Or whether they developed techniques because of the raw materials they had at hand. That would tell us new information about the times.”

For a religious work, the book has a rather exciting history, but its hazier aspects are unlikely to be discovered by a laser. It was created around the year 800 to honor the achievements two centuries before of Columb, also known as Colm Cille. He was an Irish nobleman who in Ireland and Scotland founded one of the world’s earliest Christian monastic traditions dedicated to learning and devotion.

Irish legend relates that Colm Cille, after losing a bitter legal ruling over his right to make copies of books, went into exile on Iona, the Scottish isle where the Book of Kells is thought to have been written.

But Dutch or Norse Viking raiders landed in 806, and Irish monks evidently removed the book for safekeeping. Eventually it made its way to the Kells in County Meath, a monastery outside Dublin.

There it survived new waves of raids, including one by bandits who made off with the book in 1007, according to contemporary chronicles. It was recovered two months later, under dirt, stripped of its gold covering.

The book stayed in Kells until Cromwell’s wars in the 17th century. A senior Protestant clergyman, Henry Jones, who had served as a quartermaster general for the invading army, is said to have “donated” the book to Trinity College sometime after 1661.

With the original binding lost, the book was split over the years into four volumes. Two are now on display in “Turning Darkness Into Light,” an exhibit at Trinity College, while the others are being analyzed.

The enduring mystery about whether the book was written on Iona, Kells or at another Colm Cille monastic site will likely endure. Maybe only a testing of the DNA of the vellum would reveal the age and source of the calfskins used at that time and reveal the place of the book’s manufacture. Mr. Adams would like to know if such an analysis could unlock that secret.

“I have always wondered whether a technique could tell us where the cattle were and where they came from,” Mr. Adams said. “Did the skins move around — was there a trade in the skins or were they produced locally? That would add to our knowledge. But that is what we are doing in applying these new techniques.”

There is no doubt about the book’s appeal in the present day: it attracts more than 550,000 visitors annually, vying with the Guinness Brewery tour up the road in central Dublin as Ireland’s most popular site.

Its popularity leads to crowds during the summer, and there are plans to expand its display area in the college library building, which dates from 1732. It has yet to be decided whether the book will need to be removed during any building work.

Other academics vouch for the book’s world importance. “It is one of the most precious books on the planet,” said Terry Dolan, professor of English at University College Dublin. But Professor Dolan said the book had another secret that technology would not reveal.

“Little is documented about how the book came to be removed from Kells in the first place and how it ended up in Trinity,” he said. “There is yet another fascinating mystery story there.”

The author, Cahill, is witty. I enjoyed that book several years ago, and I must get my own copy!AlicetheKurious wrote:Also, too bad schools don’t teach How the Irish Saved Civilization.

Twyla LaSarc wrote:Nordic wrote:Yeah. Its like celebrating a "Native American Day" by putting on headresses and drinking ourselves sick. Really seems a bit racist to me. But wait, Irish is white, so I guess it can't be "racist" right?

Given the fact 'St Patrick' brought the double curses of church and empire to Ireland, I have no use for the day on his account. It's like Native Americans celebrating Columbus day.

Originally in the pagan calendar, it was celebration of the green man and the first shoots of spring.

As with their native american and gypsy roots, irishness was something the my (father's) family didn't advertise and I only really found out about it in adulthood after many of the older folk were gone. My mom's family was straight up scotch and english and it is funny in retrospect how she denied knowledge of that part of my father's ancestry.

TheDuke wrote:I was quite fascinated by a theory that I think I came across through Robert Anton Wilson and various sources he pointed me to. It's along the lines that that Irish christianity evolved initially from the work of North African Coptic missionaries. It was for this reason that the Irish church was at odds with the Roman church to the point that Adrian authorised the English to invade Ireland, which was not supposed to happen between Christian nations at the time.

It was post invasion that the legend of St Patrick was created to 'explain' the existence of Christianity in Ireland. The story of St Patrick banishing snakes from the island may euphemistically refer to the stamping out of the original church.

My appreciation for this theory relies less on evidence than on intuition and perhaps a bit of wishful thinking

The Slaves That Time Forgot

Ireland quickly became the biggest source of human livestock for English merchants. The majority of the early slaves to the New World were actually white.

From 1641 to 1652, over 500,000 Irish were killed by the English and another 300,000 were sold as slaves. Ireland’s population fell from about 1,500,000 to 600,000 in one single decade. Families were ripped apart as the British did not allow Irish dads to take their wives and children with them across the Atlantic. This led to a helpless population of homeless women and children. Britain’s solution was to auction them off as well.

During the 1650s, over 100,000 Irish children between the ages of 10 and 14 were taken from their parents and sold as slaves in the West Indies, Virginia and New England. In this decade, 52,000 Irish (mostly women and children) were sold to Barbados and Virginia. Another 30,000 Irish men and women were also transported and sold to the highest bidder. In 1656, Cromwell ordered that 2000 Irish children be taken to Jamaica and sold as slaves to English settlers.

Many people today will avoid calling the Irish slaves what they truly were: Slaves. They’ll come up with terms like “Indentured Servants” to describe what occurred to the Irish. However, in most cases from the 17th and 18th centuries, Irish slaves were nothing more than human cattle.

As an example, the African slave trade was just beginning during this same period. It is well recorded that African slaves, not tainted with the stain of the hated Catholic theology and more expensive to purchase, were often treated far better than their Irish counterparts.

African slaves were very expensive during the late 1600s (50 Sterling). Irish slaves came cheap (no more than 5 Sterling). If a planter whipped or branded or beat an Irish slave to death, it was never a crime. A death was a monetary setback, but far cheaper than killing a more expensive African.

The English masters quickly began breeding the Irish women for both their own personal pleasure and for greater profit. Children of slaves were themselves slaves, which increased the size of the master’s free workforce. Even if an Irish woman somehow obtained her freedom, her kids would remain slaves of her master. Thus, Irish moms, even with this new found emancipation, would seldom abandon their kids and would remain in servitude.

In time, the English thought of a better way to use these women (in many cases, girls as young as 12) to increase their market share: The settlers began to breed Irish women and girls with African men to produce slaves with a distinct complexion. These new “mulatto” slaves brought a higher price than Irish livestock and, likewise, enabled the settlers to save money rather than purchase new African slaves.

This practice of interbreeding Irish females with African men went on for several decades and was so widespread that, in 1681, legislation was passed “forbidding the practice of mating Irish slave women to African slave men for the purpose of producing slaves for sale.” In short, it was stopped only because it interfered with the profits of a large slave transport company.

England continued to ship tens of thousands of Irish slaves for more than a century. Records state that, after the 1798 Irish Rebellion, thousands of Irish slaves were sold to both America and Australia.

There were horrible abuses of both African and Irish captives. One British ship even dumped 1,302 slaves into the Atlantic Ocean so that the crew would have plenty of food to eat.

There is little question that the Irish experienced the horrors of slavery as much (if not more in the 17th Century) as the Africans did. There is, also, very little question that those brown, tanned faces you witness in your travels to the West Indies are very likely a combination of African and Irish ancestry.

In 1839, Britain finally decided on it’s own to end it’s participation inSatan’s highway to hell and stopped transporting slaves. While their decision did not stop pirates from doing what they desired, the new law slowly concluded THIS chapter of nightmarish Irish misery.

But, if anyone, black or white, believes that slavery was only an African experience, then they’ve got it completely wrong.

Irish slavery is a subject worth remembering, not erasing from our memories. But, where are our public (and PRIVATE) schools???? Where are the history books? Why is it so seldom discussed?

Do the memories of hundreds of thousands of Irish victims merit more than a mention from an unknown writer? Or is their story to be one that their English pirates intended: To (unlike the African book) have the Irish story utterly and completely disappear as if it never happened.

None of the Irish victims ever made it back to their homeland to describe their ordeal. These are the lost slaves; the ones that time and biased history books conveniently forgot.

Is the Irish Language Spoken in Africa?

Taken from the Ulster Journal of Archaeology, Volume 7, 1859

FROM time to time statements have appeared in different quarters, asserting distinctly the existence of the Irish language, at the present day, among certain tribes in the North of Africa. Though these statements bore marks of great improbability, I considered the subject sufficiently curious to induce me to preserve a note of them, with the view of endeavouring at some time to ascertain whether they had any true foundation. The first that attracted my attention was a short notice published in the Dublin Penny Journal in 1834 (vol ii, p. 248), which was as follows:—

"About the close of the last century, a gentleman who was superintending the digging out of potatoes in the County of Antrim, was surprised to see some sailors, who had entered the field, in conversation with his labourers, who only spoke Irish. He went to them, and learned that the sailors were from Tunis, and that the vessel to which they belonged had put into port from stress of weather. The sailors and country-people understood each other; the former speaking the language used at Tunis, and the latter speaking Irish. This anecdote was related by a person of credit, and must interest the Irish scholar."

In 1845, I observed in the London Athenaeum a notice of a meeting of the Syro-Egyptian Society, at which the late Mr. J. S. Buckingham was reported to have stated that a person of his acquaintance had actually conversed intelligibly in Irish with some natives of Morocco. Being desirous of ascertaining the precise facts of the case, I wrote for information to one of the members of that Society, who in reply, mentioned that the statement had been made as reported, in a conversation which ensued after a paper on the theory of the Shemitic origin of many European nations; and that he had handed my letter to Mr. Buckingham himself. That gentleman shortly after sent me the following note:—

"Dear Sir," LONDON, JANUARY 30, 1845.

"Mr. Cullimore has sent me your letter to him on the subject of the assertion made by me at the Syro-Egyptian meeting; and I only regret you did not address me direct, as I am always ready and willing to answer any inquiries of this nature.

"You know, I presume, enough of the looseness of newspaper reporting, to be aware that it is not always correct. In this instance it is peculiarly so, both in omission and commission. What I really stated, I will here repeat. That when at Dorchester, in England, a few years ago, I received a visit from a native merchant of Morocco, whose name was Saadi Omback Benbei. He was then on a visit to a gentleman of the county, whose name I do not know. The London residence of the Morocco merchant was then at Lambeth; but I have not since seen him, so that probably he has returned to his home. He stated to me, in presence of Mrs. Buckingham, that when he was on a visit to a gentleman, near Kilkenny, in Ireland, he went one day to the post-office of that town, and hearing there, for the first time, some of the labouring people speaking Irish, he was surprised to find that he could understand their conversation; as the language had a strong resemblance to the dialect of the mountaineers of Mount Atlas, in Africa, among whom he had travelled and traded in his youth, and learned their language. He addressed the Irish labourers in this language, and their surprise was as great as his own to find that they understood him. The dialogue was very short, and on ordinary topics; but he declared there was no difficulty in understanding each other, on either side. When I was in Dublin about three years ago, I was at the Library and Museum of the Royal Irish Society [Academy], and in conversation with some gentlemen there, (one of whom I understood was the Curator or Secretary, who shewed me many Irish antiquities,) I mentioned this fact about Saadi Omback Benbei; to which a gentleman present replied, that he remembered to have heard of a Dublin lady, who came from the west of Ireland originally and spoke Irish fluently, having been married to a gentleman who was consul at one of the ports of Morocco; and that she was surprised to find herself able to converse with the mountaineers of the country (I think near Mogadore), who brought in the poultry, vegetables, and fruit to the market for sale. This is what I stated, and this I repeat. But I did not assert that I knew the Dublin lady, nor indeed did I ask the name of the gentleman who made the statement respecting her. But of the truth of all I did state, you may be assured, and may make any use of it you think proper.— I am, yours truly,

Robert MacAdam, Esq, Belfast.

J. S. BUCKINGHAM."

In Lieut. Colonel Chesney's account of his Expedition to the Euphrates and Tigris, published in 1850, I find the same incident mentioned with a trifling variation, as follows:—"During a visit made to Ireland in 1821 by Sadi Omback Benbei, then envoy from Morocco, this individual overheard some people in the market-place, at Kilkenny, making remarks on his person and dress in a dialect which was intelligible by him. He recognized it as one which was spoken in the mountains to the south of Morocco, and with which he had been familiar as a boy. The circumstance was related to Professor Hincks, LL.D., of the Munster College, by the individual himself." [vol. ii., p. 514.]

The preceding notes had been laid aside and had nearly escaped my recollection, when the following statement, which appeared in this Journal [vol. vi., p. 185], called my attention to them once more:—

"When passing through the South of Ireland a few years ago, I met a negro gentleman (Mr. Bartels) who had travelled very extensively; in fact there was scarcely any country that he did not appear to have visited. He seemed an admirable linguist; and in conversation mentioned to me that, having travelled across Central Africa, and become acquainted with the dialects there, he was able, when shown some Irish manuscripts in the library of Trinity College, Dublin, from his knowledge of these dialects, to translate several portions of them."—THOMAS HENRY PURDON. BELFAST.

The coincidence of these various statements, derived from totally independent sources of information, seemed so singular, that I felt desirous of obtaining any further particulars that could be procured in this country; and I accordingly addressed an inquiry to a gentleman whom I believed to be the best situated for hearing the opinions or reports of travellers on the subject,—Mr. Edward Clibborn, the intelligent Curator of the Royal Irish Academy. To this he has favoured me with the following reply:—

DUBLIN, 26th MARCH, 1859.

"MY DEAR MR. MACADAM,—I could not answer your note, till I saw Mr. Eugene Curry, who, I hoped, might have had some note of the name of the Consul's lady who had said she heard the Irish language spoken in a market-place in Morocco; but I find that Mr. C. had made no record, and had no exact recollection of the fact.

However, in talking over the affair, we both remembered that Mr. Buckingham mentioned the circumstance in his lectures, delivered here in the Rotunda. It appeared to both of us that the same fact had been mentioned before by another person, so that Mr. B. was not only disposed to believe it, but went so far as to say that he knew an African merchant, traveller or native, who had taken up his residence in England, and who had been able, from his knowledge of some language picked up by him in Northern Africa, to converse with Irish harvest-labourers in England.

A French gentleman assured me that he had met an Irish traveller in Northern Africa who had heard people speaking Irish there; so that it really looks as if traces of the language were still to be found somewhere or other, though hitherto I have failed in discovering the locality, notwithstanding that I have made more than one attempt to do so.

Some years since, Col. Rawdon, I believe the heir apparent to the title of Charlemont, who was visiting the Academy, happening to make some remark which led me to infer that he had been in Northern Africa, I at once asked him if he had fallen in with the people there who spoke Irish. He replied that he had not, and I think he gave a decided opinion against the truth of the report. This led to a communication with Mr. Curry, who said that he would not be at all astonished to learn that the Irish language was still in existence in Northern Africa, from the great numbers of the Irish who had been carried off as captives by the Corsairs, in the middle ages, to Africa, and had never been ransomed. According to Mr. Curry's statement, many thousands had thus been carried off from time to time from Ireland; and from a curious old Irish legend, the incidents of which are laid in the third century, it would appear that the people for whose reading this story was composed had a traditional impression or belief that African corsairs had from that period paid occasional visits to the coasts of Ireland. The fact of the discovery of the wreck of a very ancient ship on the coast of Wexford, containing two chambered cannons, made of bars of hooped iron, and said to be exactly of the same manufacture as that of guns fished up in the harbour of Constantinople, and the same as some old pieces of ordnance found on the walls of Canton, tends to raise a probability that African pirates or traders, or both of them, did visit this coast as early as the reign of Edward III., and possibly before the time of the Danes, whose visits to the Mediterranean may possibly have been intended to keep the corsairs in check, and cover their own piracies in the open seas.

Several persons visiting the Academy, besides Col. Rawdon, have spoken of the fine grey-hounds (probably of the old Irish breed) which are in Northern Africa, and of one tribe of the population, who are much engaged in the stock feeding of camels, horses, and cows, and who are called by a name or term that we might spell "Schlecht." These people possess this breed of dogs, and take great pleasure in them, though, as these are unclean animals in the eyes of good Mohammedans, such conduct is considered unlawful. Now, this word "Schlecht," or its proper vocal equivalent, is said to mean people without pedigrees, such people, in fact, as might spring from the children of unransomed captives: just the sort of people who, according to Mr. Curry's statement, might retain the Irish language if their ancestors had been prisoners carried away from Ireland.

It is amongst these people that I think an enquiry should be made for traces or remnants of Irish; for it is quite within the limits of a reasonable probability that the language might have been retained even by stealth, for the purpose of secret conversation or correspondence, and that, even now, those who might know it would be careful not to be detected in using it by Mohammedans or others, who would be suspicious on hearing people conversing in a language they did not understand.

Some years ago, the R. I. Academy was visited by several African merchants, both Europeans and natives, and I asked them about the Irish language, and put them in communication with Mr. E. Curry, our noted Irish scholar; the result of that conversation was, that they had never met the Irish language, nor people speaking it, any where in northern or western Africa. One of these gentlemen explained that in the Ashantee country, and the country near it, the names of places were all specific or descriptive in the Fantee language, which he believed to be the original local language of a large part of western, and probably of central and northern Africa; but whether that was related or not to the Irish, the African gentleman could not say. It occurred, however, to Mr. Curry to ask the meanings of the names of several places and districts, and it was thought curious at the time that, in several instances, there appeared to be real similitude between the meanings of the names of places in the Irish and Fantee languages. One of the examples, I remember, was the word Fantee itself, as applied to a very hilly district, which peculiarity it was said to imply; the corresponding word in Irish having a like signification.

I have never been able to get a vocabulary of Fantee words, to let Mr. Curry examine whether the likeness, real or apparent, in the words picked up at chance, would extend to the language further, nor am I prepared to give an opinion on the matter; still I confess I think there must be some truth at the bottom of the old tradition which brings the "Milesian" population of Ireland from Getulia, in northern Africa, notwithstanding that ethnologists claim the language of Ireland as belonging to the Japhetic class of languages. But, if Japhetic, its elementary sounds appear to be more African than European, for an educated African can read Irish manuscript with perfect accuracy as to the sounds of the letters; and thus a good ear, listening to people rapidly speaking Irish and Arabic, or that had heard one language here and the other at Morocco, being ignorant of both, might readily assume the two languages to be identical, the radical sounds being the same. In illustration of this fact, I may mention a rather amusing circumstance which occurred some years since, in the old Academy-house in Grafton Street.

Some ladies who took a great interest in Irish antiquities, invited a gentleman then in Dublin, who had been dragoman or interpreter to our Consul at Beyrout, to visit the Academy's Museum of Antiquities, to see if the objects contained in it had any similitude to things now in use in Syria. After carefully looking over the Museum, he stated his opinion that there was nothing in it that could be considered Syrian, except it might be the gold torques; but that things of this kind were made of silver in the East, and not gold, and were now made and used as offerings to churches, where they were called chains, and used as links of the chains by which the numerous lamps in the Eastern churches are suspended. On this occasion, some person present proposed to try if the Eastern stranger could read a very ancient copy of the Arabic Koran, that had belonged to the widow of the Chief of the Wahabees, and which happened, at that moment to be lying on the library table. He at once agreed to do so; and asked if he should read it as if he were alone reading for his own improvement, or whether he should read it as the Imaum did in the Mosque. We preferred the latter mode of reading it; whereupon he sent us all up to the far end of the room, and, after some movements of his body backwards and forwards, he commenced reading with a peculiar sort of cadence or chant, raising and lowering his voice, to the great amusement of the company. While the Syrian was so engaged, Mr. E. Curry came up the stairs and entered the library, and as soon as the reader stopped, Mr. Curry went on with the cadence, and, to our unpractised ears, proceeded fluently with the same story! However, on comparing notes, it turned out that Mr. Curry's cadence or musical chant was not an imitation of what he had heard, but the Irish cry or Dirge, sung by women in the south of Ireland when they come near a house in which there is a dead body. This tune or cadence is identical with that now used in the East when solemnly reading the Koran!

How is this? Can any one give us the cries or lamentations used by the Jews at their funerals, as for instance, when they sung the psalms of David in Spain? Did the Irish borrow their cries from the Jews? Are the Irish cries remnants of the songs of Sion?

Now, in the case here described, the Syrian thought Mr. Curry's words were Arabic, yet he could catch no meaning in them; in the same way the latter gentleman thought the Syrian's words were Irish, yet destitute of meaning. We, who looked on and knew neither language, thought they both used the same! And so it may be that people who do not know more than the sounds of the Irish may have inferred that they have heard Irish spoken in northern Africa, when in fact it was Arabic, or probably Hebrew or Berber, which last has sounds allied to, if not the same as, those of the Arabic.

Yours, very truly,

EDWARD CLIBBORN."

The foregoing is all the information I have yet been able to collect on this subject. It is, no doubt, quite possible that persons entirely ignorant of the Irish and Arabic languages, may have confounded the two from the similarity of pronunciation, especially as they both abound in guttural sounds not heard in our cultivated western tongues. But, if the statement of the Morocco merchant can be relied on, that he actually held a short conversation with the Irish-speaking peasants of Kilkenny, by employing a dialect spoken in the mountains of Morocco, the question assumes sufficient probability to deserve further investigation. In this country we know nothing of the dialects spoken in Northern Africa, farther than that there are such, and that they differ essentially from the Arabic used by the Moors. In all parts of the world, mountain ranges have formed the refuge of broken or vanquished tribes: hence it is that so many totally distinct languages are at present found existing among the recesses of the Caucasus. May the same not be the case in the Atlas mountains? We know that, at some remote and undefined period, the ancestors of the present Irish came from the East. The ancient traditionary history of the people themselves may not be trustworthy as to details, but it uniformly asserts their eastern origin; and modern philology corroborates this by proving the affinity of the Irish language with the Persian and Sanscrit. The old and circumstantial account of a colony established in Ireland from Spain takes us a long way on the road to North Africa; and, if true, would render it very probable that these colonists or their ancestors came previously from that country to Spain. In such case, it would not be at all impossible that some tribe of the same race may have remained and settled in the present Morocco or Tunis, and have been eventually driven to the mountains at the time of the destruction of Carthage, or subsequently by the overwhelming pressure of the Moors. Speculation, however, is useless, until we obtain more definite information regarding the supposed cognate language existing in that country; and the object of the present article is merely to place the preceding facts together on record, and to direct the attention of competent inquirers to a curious subject.

ROBERT MACADAM.

slad wrote:It is, no doubt, quite possible that persons entirely ignorant of the Irish and Arabic languages, may have confounded the two from the similarity of pronunciation, especially as they both abound in guttural sounds not heard in our cultivated western tongues.

Users browsing this forum: No registered users and 160 guests