"We have to recalibrate our notion of abundance"

With the writer and journalist Richard Seymour

Just one last question. In various moments in our conversation you talked about social media, calling it 'the social industry'. Your latest book, The Twittering Machine, is about that. Why is it that you consider this such an important issue?

First of all, the reason I call it 'the social industry' is that, to call it social media is a kind of propaganda: all media are social. It is akin to calling cigarettes 'friendship sticks': they can be used that way, but that's not what they are for. They are a delivery mechanism for cancer, based on an addictive mechanism. And that's what we are talking about. The industry is based upon, obviously, the extraction of data, as its raw material, which is extracted by a certain amount of free labour. If you think about it, globally, the average internet user spend 135 minutes a day on one of this apps. This is a lot of time. Take the figures with a pinch of salt, but they illustrate the scale of this. If you were to calculate that over a lifetime, the global average life expectancy of 71 years, that would be around 50,000 hours. I was talking about the good life earlier, imagine the sort of project that you might embark on with 50,000 hours. This industry has turned leisure time into its time. They offer it as a tool, or as leisure, so that you don't even notice the work.

And I thought, what is the incentive? Why spend all that time on the social industry? You are not spending that much time meeting people face to face, and that means this is your social life now. Looking at a screen is your social life. As Marxists, we are very interested in social relations, and this is how social relations are being reorganised in a capitalist way. And it actually reminds me of what Adorno called 'the culture industry': a massive industrial system that homogenizes culture on the format of the commodity. It integrates us from above and results in a very narrow and conservative culture, with conventional ways of thinking constantly reiterated. Now, he probably over-estimated this and overstated the uniformity of the Hollywood production line. But nonetheless, it has something to it. But far more than that, the social industry does exactly this: it integrates you from above and it subordinates you to - it's not even a question of the commodity format - you are obeying protocols and algorithms that are hard written into the system. They are not even seen, they are taking for granted as the precondition for being there. And these are what Althusser called interpellation mechanisms: they interpellate you because as soon as you sign up you get a profile picture, a little description, you have to provide certain kind of content, and act in a certain type of way. You are a certain kind of subject. And your social subjectivity is now programmed, literally programmed in a way that it never has been before.

This is a revolution in social relations, along very capitalist lines. But it's not just capitalist lines. There is interesting research by Alice Marwick who used to work in Microsoft and found that the values of the social industry are the values of the sort of people who made it, and that is rich, white men in Northern California. They are values of hierarchy, status, competition, celebrity and celebrity worship. That reflects the life experience of a very small section of humanity, but now it's being universalized. Forget about the Hollywood dream factory, that's got nothing on the sophistication of this ideological machine. Forget about millionaires buying newspapers to broadcast their ridiculous views for the sake of some ideological mission. This is way more subtle, because the social industry is so massified and yet so personalized. The algorithm is very good at listening to you. It's a listening devise, that hears everything that you say and automatically calculates... without even intending to, it registers your unconscious, aggregates it, and then splits it up in demographics and sells it back to you as a commodity experience. It commodifies your unconscious.

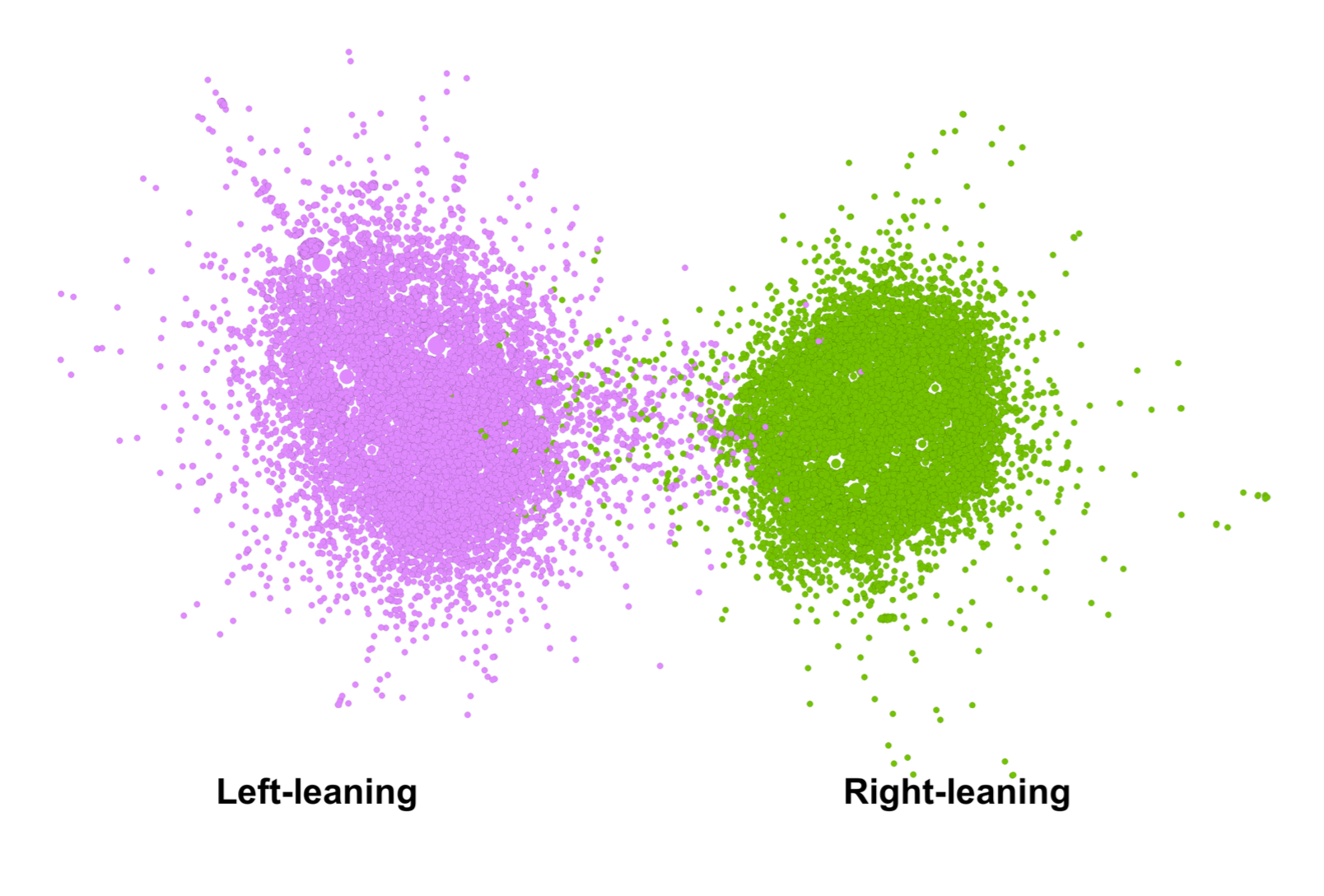

One example: on this website you can buy a t-shirt saying 'Keep Calm and Rape a Lot' or stuff like that. What does this mean? It means that some people were searching for this and the guys who made these t-shirts, they didn't even have to think about it, they just, automatically, by algorithm, advertised they could make these t-shits, and they must have gotten enough orders. The algorithm works the same way on Youtube, where it picks up on watch-time, scrolling, click throughs. So we ask, why has the far right been so successful on Youtube? The far right is way ahead of the pack, way ahead of the Left and the liberals. And one of the things that we know about the social industry is that they don't select by the accuracy of the information or edification, they select for material in your feed that is going to have a somatic impact, that you'll react to, so that you feel you have to type something back, or so you keep watching Youtube. And for some reason, conspiracist material in particular is addictive. And that's what you get with the far-right: conspiracist infotainment, Islamophobia, antisemitism, Holocaust revisionism, the Hillary Clinton 'sex slave' scandal. This infotainment also delivers a kind of narcissistic pleasure: 'I've figured it out while the sheeple haven't worked it out'. This has proven to be incredibly powerful, especially when nobody trusts politicians or the old media. Why should you trust them? They are liars! They are right about this. The traditional modes of hegemony are breaking down.

Through these spaces you get infotainment, and you also get the culture wars. It's interesting that the internal identity politics of this industry is such that you have to spend your entire time crafting a public identity for yourself, as an online micro-celebrity. When you get caught up in this medium, you tend to get wrapped up in these online disputes and you have to engage in taking sides in a way that is a lot more rigidified that otherwise might be. And I'm not talking as much about political polarization, as about cultural balkanization, identity essentialism. And so you get these culture wars, and spitting out of these culture wars you get alt-right cultures such as what came out of the #gamergate. So this industry is the most profitable industry in the world, so Google, Facebook, they are beating out oil companies. That's changing our mode of production, it's also changing our politics.

Although it was inaugurated by Clintonite liberals and welcomed by the Obama administration, it seems that paradoxically the unconscious of the system is proto-fascist. So I think, given that we are at a moment in which the future of humanity really is at stake, it is ominous that our social lives are being re-written in this way by people, technologists and the companies they work for, who don't respond to our internets, needs or demands. And they have a lot more political power, in some ways, than elected politicians. We need to use the democratic avenues that are open to us, however diluted they are, to reform this in a radical way. One possible way to begin to that is to - first of all tax the hell out of them, because they are making enormous profits - but more importantly, we need some publicly owned platforms. In this country we've got the BBC, which is not great, but it is based on the idea of 'public service broadcasting'. Why can't we have a public service internet? So we can make practical, concrete reforms, by which we rapidly democratise these things. That's why I think it's important.

https://www.patreon.com/posts/we-have-to-our-29625670