Notes on Trump (Bromma Dec. 2016) 1. The normality of white supremacy

1. The normality of white supremacySince Trump’s election, I keep hearing that we shouldn’t “normalize” him or his agenda. I believe that’s looking through the wrong end of the telescope. There’s nothing as “normal” in the U.S. as white supremacy. Sometimes it’s disguised by tokenism and obscured by “multiculturalism.” But in this country, white supremacy has always shown its true naked face at times of stress and transition.

Because white supremacy isn’t just a bunch of bad ideas inherited from ignorant elders. It’s a deeply-rooted institution through which the U.S. rules over many oppressed peoples. It’s the glue that keeps hundred of millions loyal to that very same program. It’s the central ideological, political and physical system set up by white capital to rule the land and dominate its internal and external colonies. And therefore white supremacy underpins all the wealth and power this country’s ruling class possesses. Without it, the U.S. falls.

2. Contradictions within white capitalismWhite supremacy is constant, but it keeps changing form. For instance, African Americans have endured a variety of modes of white supremacy: slavery, Jim Crow, gentrification, and more. White capitalism welcomed Mexicans and Chinese as semi-slave laborers, then attacked and deported them when conditions changed. Native peoples faced extermination campaigns, phony treaties, forced assimilation and confinement on reservations at various times. White supremacy isn’t a singular strategy by white society towards people of color. The form can change, as long as whiteness is always valued; as long as white people are always on top.

U.S. white supremacy was modified in response to world anti-colonial struggles and, after the Cold War, to globalization. Together these developments generated significant contradictions for traditional forms of white supremacy. By the late 1970s, old-style white military colonialism had lost much of its power, beaten back by a phalanx of national liberation struggles. So imperialism rebooted, searching out colonial partners and new forms of financial blackmail to replace or supplement military occupation. And, in the 1990s, U.S. capitalism entered a period of intense cooperation with other capitalists around the world, aiming to make the global economy increasingly “borderless.” Open, blatant racism wasn’t helpful in this changed environment.

So the U.S. ruling class adapted white surpremacy to the new conditions and gave it a new look. In the revised, neocolonial order, some people of color were accepted into positions of wealth and authority. Racist violence and discrimination continued inside and outside the country. But at the same time, U.S. high culture increasingly professed to celebrate the diversity of people of all nationalities and races (and genders too). This helped present U.S. capitalism to the world with a friendlier face. White supremacy continued, masked by capitalist multiculturalism.

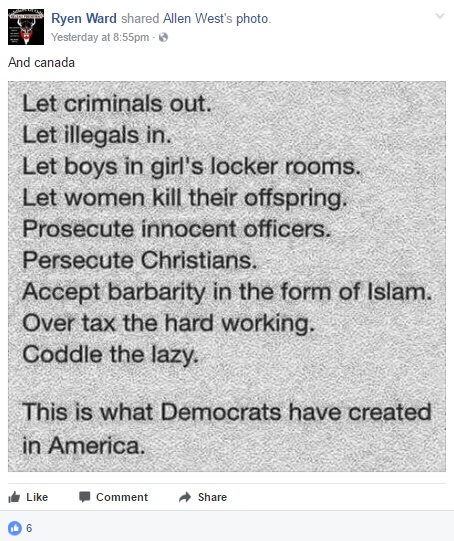

Some white people embraced the concept of multiculturalism, sincerely hoping it could be the basis for a genuine progressive culture. But most white amerikans felt that this new incarnation of capitalism was a demotion. They didn’t like having people of color as their bosses. They didn’t like seeing “good jobs” and social bribery spread around the world, instead of being reserved for them. And they hated the “political correctness” of having to hide their racism. U.S. capitalism’s perceived “disloyalty” to its white home base during the rise of globalization fueled the current upsurge of right wing populism, including eventually the campaign of Donald Trump.

But for quite a while the ruling class turned a deaf ear to its disgruntled white masses. The capitalists had global interests to tend to; global profits to bank. And frankly, a willing Asian dictator or Latina judge or African American president was worth more to them than a thousand whining white people. The militia movement was repressed when it became militant; the Tea Party was mocked by the global sophisticates. (Neither was destroyed, though; they remained as a possibility, a fallback.)

As globalization continued to advance in the last few decades, white amerika was gradually forced and cajoled to accept modest changes in the hierarchy of imperial privilege. It seemed possible that monopoly capital, pushing white people to fall in line with multiculturalism, might continue forever along that path, backed and cheered by cohorts of optimistic and idealistic artists and intellectuals.

To a large extent, this is where the plaintive cry not to “normalize” Trump comes from. Cosmopolitan liberals, now accustomed to living under globalized capitalism, can’t believe that U.S. society is going to be allowed to go backward; can’t believe that a rich country could ever be permitted to trash multiculturalism; to turn back the clock on women’s rights and environmentalism and so much more. They have a hard time accepting that their bright dream of a blended world culture, a dream that had previously been tolerated and even encouraged by monopoly capital, might be betrayed, and end in a surge of old-fashioned racist violence. Their disbelief echoes the disbelief among the liberal intelligentsia in England after Brexit, and in other countries where globalization is giving ground.

3. Timing is everythingIt’s important to understand that populist opposition to globalization in the West is making breakthroughs not as globalization rises, but as it falters. In fact, the rise of these political movements is probably more a reflection of globalization’s decline than the cause of that decline. What’s coming into view, semi-hidden underneath the frenzied soap opera of reactionary populism, is that the tide of globalization has crested and started to recede. It wasn’t permanent after all.

It should be stipulated, right off the bat, that globalization has unleashed immense changes, many of which are irreversible. For example, the peasantry, once the largest class of all, isn’t coming back. Globalization broke it; sent it streaming out of the countryside by the hundreds of millions. Out of that broken peasantry, a giant new woman-centered proletariat and a sprawling lumpen-proletariat are still being formed around the world.

Yet globalization as a financially-integrated, transnational form of capitalism can’t advance without constant expansion, constant profit growth. Since no global state exists to mediate among the world’s capitalists, shared growth is the only thing that restrains them from cut-throat competition. Growth is also what allows capitalists to at least partly mollify the displaced masses back home with cheap commodities and whatever jobs a rising world economy has to offer. But now, instead of growing, the world economy is slowing. In fact globalized capitalism, having bulked up on steroidal injections of speculation and unsustainable, leveraged debt, is teetering on the edge of disaster.

From the U.S. to China, from the Eurozone to Brazil, danger signs are flashing; massive globalized industries are shifting into reverse. International trade and investment are flat or falling. Capital that was formerly used for investment in “emerging economies” is now flowing backward into safe haven investments in the metropolis. Automation, renewable energy and other new technologies are starting to shorten supply chains, reducing the demand for imports from far away. Intractable economic and political crises, like those in the Middle East and Greece and Ukraine, are eroding cooperation and sapping confidence in already-weak globalist institutions. The internet, a key factor in globalization, is gradually becoming segmented, as governments and corporations privatize, censor and manipulate parts of it. And underneath everything, the increased inequality caused by globalization itself is throttling the demand for commodities.

Multinational corporations aren’t abandoning world markets by any means. But leading monopoly capitalists are hedging against trade wars and reducing their reliance on complex, interdependent trade and finance. Facing what he calls a “protectionist global environment,” GE CEO Jeffrey Immelt is shifting his company’s production from a globalized to a “localized” model. “We used to have one site to make locomotives; now we have multiple global sites that give us market access. A localization strategy can’t be shut down by protectionist policies.” This is a defensive posture, harkening back to an earlier form of imperialism.

Once it seemed that transnational integration had an unstoppable momentum. But now a retreat into the once-familiar zones of old-fashioned nation-based imperialism seems to be on the capitalist menu.

4. A previous wave of globalizationIf the ongoing shift away from from transnationalism and towards harsh national rivalry continues, it won’t be the first instance of “de-globalization” in modern history. It’s happened before.

From 1870 to 1913, fueled by the industrial revolution and the explosive rise of U.S. capitalism, there was a massive spike in international trade and market integration. It was centered in Western Europe and the U.S., but extended further into Latin America and other parts of the world. Borders were opened, tariffs were lowered, and there was a rapid increase in exports and financial interdependence. The world capitalist economy boomed. Just as during the current wave of globalization, this earlier period was marked by major innovations in transport and communications, as well as an unprecedented upsurge in transnational migration. (Including tens of millions of workers who migrated from Europe to the U.S.) Economists refer to this as the “first wave” of modern globalization.

But capitalism is at best an unstable and contradictory system, periodically riven by economic crisis. And a globalized form of capitalism appears to be particularly vulnerable to those crises.

The globalization of 1870-1913 collapsed like a house of cards. Growing economic imbalances and stalled growth led many imperialist countries to impose tariffs and take other protectionist measures, vainly striving to boost their own home economy at the expense of others. Inevitably, there was retaliation in kind. This cannibalistic inter-imperial competition only aggravated the already deteriorating economic conditions. Trade and global commodities became more and more expensive. There was a rapid downward spiral of economic depression and reactionary nationalism.

There was no pretense of multiculturalism in the U.S. back then, of course. Massive vio-lence against people of color was already common during the boom years of globalization. So it’s hard to say if racism became worse during the period of de-globalization. But in 1913, segregation was officially initiated in all federal offices, including lunchrooms and bathrooms. In the following decades there were dozens of vicious race riots against Black enclaves in cities North and South, causing many hundreds of deaths and thousands of people driven from their homes. Having been pushed down previously, the Klan was revived in 1915. Its peak was in the 1920’s, with some 4 million members.

Finally, the first wave of globalization imploded in a frenzy of national hatred and two brutal world wars, fought without quarter among the capitalist powers. Something we should keep in mind as we confront the current situation.

5. De-globalizationToday’s capitalist globalization isn’t failing because of political blows landed by Western anti-globalization movements, although those have had a real effect. Rather, the populist movements are reaching for real power just as chunks of the ruling class globalist consensus are themselves breaking away and seeking alternate, nationalistic strategies.

Former globalizers are floating back toward the anchors of their old home economies and shifting the blame for economic crisis onto “foreigners” and social minorities. They’re muting their former advocacy of free trade while backing away from trade agreements. They’re rediscovering protectionism. They’re experimenting with cyber-attacks on other countries, building up their militaries, increasing their involvement in proxy wars, and manipulating their currencies to gain temporary advantage over trading partners. And as a natural part of this shift, they’re unleashing their most rabid “patriotic” social bases to sell their new/old program, control the streets, and, potentially, to serve as cannon fodder down the road.

In every quarter of the globe, nationalistic xenophobia is on the rise, strangling the remaining globalists’ fading dreams about world government and a borderless economy. Right wing populism is being released, and it’s rising out of its reservoirs, flowing like water filling dry river beds. In country after country, old social prejudices are being revived and intensified; former globalist capitalists are reaching out and mending fences with their most trusted national social bases.

That’s how it is here in the U.S., too. A return to the old white amerika is becoming a more and more practical program for U.S. capitalists—not just for the white masses. It offers the only natural form of capitalist regroupment as globalization wanes. An option as amerikan as apple pie.