Moderators: Elvis, DrVolin, Jeff

JackRiddler wrote:First three weeks:

David Christian, Maps of Time: An Introduction to Big History, 2006.

What I'd wish I'd written, if I'd ever had the patience and persistence to seriously study a bibliography of All Knowledge and try to wrap it into a single narrative from the physical underpinnings of the universe through star formation, plate tectonics and the evolution of life to the rise of hominids, agrarian civilizations and the modern revolution.

JackRiddler wrote:.

First three weeks:

David Christian, Maps of Time: An Introduction to Big History, 2006.

What I'd wish I'd written, if I'd ever had the patience and persistence to seriously study a bibliography of All Knowledge and try to wrap it into a single narrative from the physical underpinnings of the universe through star formation, plate tectonics and the evolution of life to the rise of hominids, agrarian civilizations and the modern revolution. Got it thanks to Jeff Wells's recommendation, and I endorse it as outstanding reading, with the caveat that of course, given the scope, the engaged reader is certain to find reasons for objection along the way. Mine were greatest at the beginning, with the uncritical acceptance of Big Bang cosmology, and at the end, with a rather superficial and milquetoast treatment of the 20th century.

The first highlights one of the limits of the Big History approach: a historian lacks the position (and likely the inclination) to contest the contemporary mainstream view within a given natural science; who is he to go against what most cosmologists say, even if it's suspect? Especially when the next chapter deals with the origins of the Solar System, and the ones after that are due to cover all of modern geology and biology. All a suitably modest historian can do, at least if he wants to avoid looking like an overambitious crackpot, is to faithfully summarize current consensus paradigms within each discipline. I appreciated the first couple of hundred pages as a damn good review of all the science that I had, in recent decades, largely forgotten. Christian covers himself by calling it all a "modern creation myth," one that unlike traditional creation myths is subject to revision.

The 11 timelines, which start at a 13-billion-year scale and come down to the last 1000, and the many other very judiciously chosen big-picture data sets are among the book's many truly fantastic resources. As for the weakness at the end, having made such an effort to tell all history from the perspective of 21st-century scholars, he should have added another hundred pages to cover the near-present and the scenarios of the immediate future more adequately. But it's probably also related to a risk-averse approach; if he's as bold about the present as he at times ventures with earlier periods, he runs the danger of having his whole approach denigrated as "controversial." So, for example, we get too much Giddens and little critique of the globally dominant market ideology and the havoc it has wreaked. I'd also accuse this book of paying insufficient attention to the role of individual psychology and human irrationality, sheer and yet systemic. (Dr. Freud is an interesting omission from the Index.) But reading this book stirs thoughts about everything, literally, and is intensely rewarding. I'd add it to a core curriculum and I'll probably return to it often, but shall resist writing a 10,000 word review just yet.

http://www.amazon.com/Maps-Time-Introdu ... 168&sr=1-1

"So here is the thought experiment: what knowledge from today would be most valuable to these survivors as they tried to rebuild their lives and repopulate the earth. What has humanity discovered or invented in the last ten thousand years of human civilization that would be most useful in rebuilding civilization in the aftermath of such a global catastrophe. For this thought experiment, you get to choose one book to pass on to future generations."

[url=http://www.grassie.net/articles/2009_A_Thought_Experiment.html] A Thought Experiment:

Envisioning a Civilization Recovery Plan[/url]

By William Grassie

Join with me in a thought experiment. Imagine a major planetary catastrophe. It could be a global nuclear war, a devastating pandemic, or perhaps rapid climate change. It could be a sleeper computer virus. The Unix equivalent of rm * on all the computers of the world, wiping out all of the digital memory banks at some future date. In any of these scenarios, we would anticipate an economic and therefore also environmental collapse, though not necessarily in that order. The catastrophe would directly and indirectly involve a massive die off of human populations.

Like the White Queen in Lewis Carroll Through the Looking Glass, I find it useful to practice imagining these "impossibilities" a little bit each day. "When I was younger I always did it for a half an hour a day," the Queen tells Alice. "Why sometimes I believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast." [1] It is not bad to think of these impossibly dark possibilities. Contemplating one's own death, or even the death of billions, feels impossible, even though it is always a certainty from the day of our birth. Reflecting on death is an important part of spiritual practice in many different traditions. A little bit each day is a great way to focus life on really important matters. Taking the White Queen's lead, I try to do my imaginings before breakfast, so I can focus the rest of the day on accentuating and appreciating the positive in life.

The point of this thought experiment, however, is not to contemplate death and disaster, but to imagine survivors and continued life. My question is what knowledge contained in what books of science, culture, and civilization would you most want to pass on to the surviving humans as they faced the prospect of adapting to this new environment and rebuilding their lives over many generations. You get to choose one book, not the whole Library of Congress.

For the purposes of this thought experiment, I imagine a natural catastrophe, not a human-caused catastrophe, because I do not want to introduce morality and culpability into the equation, not yet at least. Let's imagine something in the order of the Mt. Toba supervolcano, which blew up in Sumatra, Indonesia some 73,000 years ago. This super eruption, estimated to be three thousand times greater than the 1980 eruption of Mount Saint Helens, changed everything for our hunter-gatherer ancestors overnight. The volcanic ash released in the atmosphere reduced average global temperature by 5 degrees Celsius for seven years and triggered a global ice age. The Indian subcontinent was covered with 5 meters of volcanic ash. Humanity was reduced to some 1000-to-10,000 breeding pairs. And yet we, and the other flora and fauna, survived, and as the sky cleared and the ice slowly retreated over the millennia, we resumed our expansion. Over time humans migrated to every continent except Antarctica. We are all descendents of these survivors, a story written in our mitochondrial DNA. [2]

One of the thirty or so supervolcanos active in the world today is the Yellowstone Basin. The caldera is about 72 kilometers across. Over the last 16.5 million years, Yellowstone has blown up about a hundred times. The last three super eruptions occurred 2.1 million, 1.3 million and 640,000 years ago with a number of minor lava flows in between. Let's be clear about the scale of such an event. The eruption that occurred 2.1 million years ago covered California under 6 meters of volcanic ash and New York State under 20 meters of volcanic ash. As with the more recent Mt. Toba supervolcano, it was accompanied by the onset of a sudden global ice age. [3]

So in this scenario, the United States disappears in the course of a few days. It is hard to argue with geology. There would be 300 million dead in short order and the breadbasket of the world gone. The rapid cooling of the atmosphere would further accentuate massive famines around the world. Global trade and industry would grind to a halt. The survivors would be reduced to subsistence farming, gathering, hunting, and fishing in areas around the earth's equator. For our thought experiment, let's say that humanity is again reduced to some 10,000 breeding pairs dispersed along the tropical and sub-tropical zones around the world.

So here is the thought experiment: what knowledge from today would be most valuable to these survivors as they tried to rebuild their lives and repopulate the earth. What has humanity discovered or invented in the last ten thousand years of human civilization that would be most useful in rebuilding civilization in the aftermath of such a global catastrophe. For this thought experiment, you get to choose one book to pass on to future generations.

Of course, different people would answer that question based on their biases and prejudices. A devout Muslim might say that the most important book to pass on would be the Qur'an. A devout Christian would presumably privilege the Bible. A Buddhist might argue in favor of the Pali Canon. A Hindu might pick the Vedas or the Upanishads, but these are actually libraries of manuscripts, and not single books. I am going to put my trust in the Holy Spirit, God-by-whatever-name, to help the survivors without the benefit of one of these sacred books.

There would also be regional variations of this parochialism. American exceptionalists might most want to see their beloved Constitution or an American history book passed on, even though there would no longer be any Americans surviving the Yellowstone eruption. Russians, Indians, Chinese, and so forth would all favor the preservation of their own exceptional regional histories and cultures.

This cultural and geographical parochialism is likely to carry over into the sciences and humanities. A physicist might argue in favor of knowledge of fundamental atomic building blocks. A physician might argue in favor of the knowledge of microbes, vaccinations, and antibiotics. A professor of literature might argue for Shakespeare or some other author of note. An economist might chose Adam Smith or Friedrich Hayek. A philosopher might choose Plato's Republic, or God forbid, Heidigger's Being and Time. You get the picture. It would be frankly pathetic and tragic if all that remained of ten thousand years of human civilization were the local histories of one region or nation, one religion or tribe, one ideology or disciplinary bias.

Stockpiling food and weapons in the mountains of Idaho would be a silly and small-minded emergency plan for the scenario I am describing, in the first order because anywhere in North America would be the wrong place at the wrong time. Instead of focusing on the survival of my tribe, my family, or myself, we need to focus on the survival of civilization, of what is most precious and useful to future generations. And the only way to do this with assurance is to distribute the most valuable and practical knowledge as widely as possible across the planet today in anticipation that unfortunate day. How do we give the survivors a head start? What information would be most useful in rebuilding human civilization in the event of such a horrible collapse? Remember the best and the brightest, the most privileged and most educated, are not likely to survive in any great numbers. You get to choose one book for the survivors to help them rebuild civilization.

The book I would chose is Maps of Time: An Introduction to Big History, by David Christian (2004).[4] There are other books in this genre.[5] I can imagine even better books in the future, but for now David Christian does a remarkable job in putting 'it' all together. It is the combined history of the universe, our creative planet, and our restless species. I want to argue that the most useful information for the long-term survival of our species is this macrohistory from the Big Bang to today. It goes by different names – the New Cosmology, the History of Nature, the Epic of Evolution, and Big History. Whatever we call it, it spans some 13.7 billion years from the primordial flaring forth of the early universe to the rapid flaring forth of our global civilization in the last century. I like to call it Our Common Story, because for the first time we have a progressively factual account of the universe and ourselves that encompasses all religions, all tribes, and all times. This grand history is perhaps the most remarkable achievement of human civilization.

The scientific metanarrative is quite new and still evolving. In brief outline, this omnicentric universe began some 13 billion years ago as infinite heat, infinite density, and total symmetry. The universe expanded and evolved into more differentiated and complex structures – forces, quarks, hydrogen, helium, galaxies, stars, heavier elements, complex chemistry, planetary systems. Some 3.5 billion years ago, in a small second or third generation solar system, the intricate processes called "life" began on at least one small planet. Animate matter-energy on Earth presented itself as a marvelous new intensification of the creative dynamic at work in the universe. Then some 2 million years ago, as if yesterday in the enormous timescales of the universe, proto-humans emerged on the savanna of Africa with their enormously heightened capacities for conscious self-reflection, language, and tool making. Ten thousand years ago agriculture begins and with it growing populations of humans living in ever larger and more complex societies. And this unfolding leads us all the way to today, six billion of us collectively transforming the planet and ourselves. The wonder of it all is that each of us is a collection of transient atoms, recycled stardust become conscious beings, engaged in this global conversation, brought to you by ephemeral electrons cascading through the Internet and bouncing off of satellites.

Maps of Time provides this overview in six parts, fifteen chapters, eight different timelines, nine maps, thirty-nine charts, two appendices, over six hundred references, all bound in one big book. The story of the universe and the evolution of life are covered in the first hundred and forty pages. The remaining four hundred some pages detail the evolution of humans, the rise of agriculture and agrarian civilizations, and the great acceleration of the modern era. That seems like the right balance for a survival manual for human civilization. David Christian is a skilled historian and storyteller. He provides not only the macrohistory, but explains the evidence for why we know it to be so and when the evidence might be inconclusive. He is generous in crediting others. The book is now also available from the Teaching Company as a series of audio or video lectures.[6]

David Christian not only lays out the facts in a compelling narrative, but he interprets the large-scale patterns of transformation at different scales. For instance, he writes:

In the early history, gravity took hold of atoms and sculpted them into stars and galaxies. In the era described in this chapter, we will see how, by a sort of social gravity, cities and states were sculpted from scattered communities of farmers. As farming populations gathered in larger and denser communities, interactions between different groups increased and the social pressure rose until, in a striking parallel with star formation, new structures suddenly appeared, together with a new level of complexity. Like stars, cities and states reorganize and energize the smaller objects within their gravitational field. (245).

So we are not only recycled stardust (the atoms in our bodies), empowered by the sun through photosynthesis (in the food we eat and fossil fuels we burn), but our own human cultural patterns of complexification may be analogous to that of star formation. Sweet!

Catastrophic collapses, however, are part of the big story. These have happened throughout the long evolutionary history of our planet with at least seven mass extinctions. To a lesser degree, they have also happened throughout the rise of human civilization. Civilizations do not last forever. Farmlands become deleted. Famine and disease cause population declines. Internal conflict and external competition lead to wars and the destruction of cities and the eclipse of entire civilizations. May it not happen in your lifetime, but it will happen in someone's lifetime, some time in the future. How do we prepare?

In the face of a catastrophic collapse of human civilization, we need to pass on useful information that will survive a long period of impoverishment in isolated communities around the world as they rebuild over many generations. Remember in this scenario, humanity is back down to 10,000 breeding pairs dispersed around the globe, initially eking out their subsistence in extremely reduced environments. Most modern technology will be nonexistent. Sorry, but your iPhone is not going to be much use. If it is ever to exist again, such technology will need to be reinvented, along with most of agriculture, medicine, engineering, economics, politics, art, music, morality, and religion. This is not going to happen overnight, but it could happen over many generations.

Curiously, most of us today, even among the best educated and most privileged, do not really know much about this incredible New Cosmology pieced together by scientists in diverse disciplines. There are precious few undergraduate courses that expose students to this Big History.[7] Only a few attempts have been made to systematically teach this Epic of Evolution at the K-12 level.[8] I know of no seminaries or business schools for that matter that teach Our Common Story. Fortunately, we now have a number of books, not just David Christian's, which attempt to bring it all together, but the books and the ideas contained therein, are not widely distributed, studied, taught, interpreted, and debated.[9] The broadest possible distribution of this new user-manual for Earthlings is the key to the survival of this precious knowledge.

It is not just a beautiful and amazing story; it is also a very practical story. If future generations had the basic outline of this story, the woof of emerging complexity and the warp of space-time, they would know where to focus their own intellect and creativity as they sought to rediscover and reinvent science, technology, agriculture and human culture. They could start looking for atoms, molecules, microbes, and cells, even if they lacked the tools to do so. They would know of something called the Periodic Table and have a head start on rediscovering and reinventing modern chemistry. They would know something of metallurgy, indeed of the possibility of flying machines and space ships. They would understand the motion of the sun, moon, and stars. They would know of galaxies, even though they could see none.[10] They would quickly rediscover and reinvent advanced mathematics. They would understand that we are Earthlings, who evolved from other life forms on this dynamic, creative, and sometimes dangerous planet. They would know that some plants and animals can be domesticated, and that even the wild flora and fauna are our close relations. They would understand the importance of energy density flows and creative innovation processes. They would not only speak, read, and write; they would understand something of the evolved human brain and body that enables these miraculous accomplishments within the mutual aid and collective learning of human societies.

It turns out that this Epic of Evolution may also be important information if we are to successfully meet the other challenges of the twenty-first century. The story includes insights into how nature functions as complex, distributed systems, and the dangers of run away environmental problems. It includes new insights about economics and how complex, distributed economic systems produce incredible wealth, as well as dangerous dysfunctions. It includes important insights about war and violence, including the technological, psychological, economic, and biological evolution of conflict in human history. It includes insights about the importance of limited governments and individual freedoms and responsibilities. It includes insights about the deep time of the cosmos and the rather unique moment in space and time in which humans find our selves. It includes practical knowledge about the great problem of the twenty-first century and fundamental principles that inform how these challenges should be addressed. Our Common Story gives humanity new perspective, a vantage point, which takes the edge off bitter ideological, nationalist, and religious conflicts around the world.

This then is the real take-home message. Our Common Story helps orient humanity towards pragmatic problem solving in dealing with our contemporary challenges – war and peace, economics and the environment, education and innovation, health and happiness, freedom and responsibility.[11] It may just be that distributing this knowledge as broadly as possible throughout the world today is also the key to solving our twenty-first century problems. We may not be able to prevent the next supervolcano, but we can certainly prevent the many evils and stupidities that we inflict on each other and the planet.

The point of this dark thought experiment is to finish up before breakfast. Recalling Alice's discussion with the White Queen, one should probably not dwell on these "impossible" apocalyptic possibilities for more than a half an hour everyday. Considering such "impossibilities" is a kind of looking glass back on ourselves and through which we can also help future generations. The point of this thought experiment is to wake up and pay attention to the larger drama in which we live each day and to focus our thoughts and actions on crafting a safer and healthier future.

Our Common Story is really quite a positive story, one in which the universe seems to repeatedly err on the side of elegant improbabilities. May it always be so in the long arc of time. The most important knowledge that humans have gained in the ten thousand year march of human civilization is the history of the universe, our planet, and our selves. Hopefully many other books and tools would also survive some future cataclysm, but if our descendents only had this Big History, they would have an enormous head start on the challenges of rebuilding human civilization. May that day not be in our lifetimes, or our children's children lifetimes, but some day it will be so, if past performance is any guide.

Knowledge of the Epic of Evolution would vastly accelerate the rediscovery of science, the reinvention of technologies, and the recovery of civilization. Our descendents would understand the remarkable cultural achievements of past civilizations and be inspired to create their own, resuming and exceeding us in our quest to return to the stars. Rebuilding human civilization may well take them thousands or tens of thousands of years in this post-cataclysmic world, but we may take comfort in knowing that we have passed on this hard won knowledge. Our descendents in turn will remember us always with gratitude for having bequeathed them this great gift.

The clincher, of course, is that Our Common Story also turns out to be essential for saving human civilization from its own self-destructive tendencies. The challenge then is to distribute that gift as broadly as possible today, and in so doing perhaps also help solve the great anthropogenic challenges of the twenty-first century.

Avalon wrote:Sounds like a fascinating book.

But did I miss something, or did Grassie somewhere say why he thinks people would passing on the ability to read and comprehend such a book if it were surviving and available in the local language or there were English speakers and readers?

His thought experiment seems to be a rather pointless exercise if you can't get beyond the reading problem.

David Christian in Maps of Time, p. 10 wrote:If paid intellectuals are too finicky to shape these stories, they will flourish all the same, but the intellectuals will be ignored and will eventually disenfranchise themselves. This is an abdication of responsibility, particularly as intellectuals have played such a crucial role in creating many of today's metanarratives. Metanarratives exist, they are powerful, and they are potent. We may be able to domesticate them; but we will never eradicate them. Besides, while grand narratives are powerful, subliminal grand narratives can be even more powerful. Yet a "modern creation myth" already exists just below the surface of modern knowledge. It exists in the dangerous form of poorly articulated and poorly understood fragments of modern knowledge that have undermined traditional accounts of reality without being integrated into a new vision of reality. Only when a modern creation myth has been teased out into a coherent story will it really be possible to take the next step: of criticizing it, deconstructing it, and perhaps improving it. In history as in building, construction must precede deconstruction. We must see the modern creation myth before we can criticize it... Ernest Gellner made this point well in the introduction to his attempt at a synoptic view of history, Plough, Sword and Book (1991): "The aim of the present volume... is to spell out, in... perhaps exaggerated outline, a vision of human history which has been assuming shape of late, but which has not yet been properly codified... formulated in the hope that its clear and forceful statement make possible its critical examination."

smiths wrote:a book that i think is similar in scope but different in big ways to Maps of Time: An Introduction to Big History, 2006 is

Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge by biologist E. O. Wilson.

it totally blew me away when i read, very inspiring in a lot of ways and i'd recommend it for a great big picture

Paul Fitzgerald and Elizabeth Gould write in a guest op-ed for Juan Cole's blog wrote:

Fitzgerald & Gould: Afghanistan, a New Beginning

“Rebuilding Afghanistan is the most cynically pro-American thing you could do anywhere in the world in terms of making it a strong ally in the best sense of the word. Not a puppet or a right-wing military dictatorship but a really good Islamic country that has the potential to be democratic and progressive and lead this whole part of the world.” – Rob Schultheis, an American journalist in Kabul, 2002.

As the Obama administration unveils its new and expanded war plan for Afghanistan and Pakistan, word comes that it has downgraded the so called democracy-building efforts of the Bush administration, that it will negotiate with the so called “moderate” elements of the extremist Taliban and that it may take a more direct role in running the government of Afghanistan.

President Obama’s special representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan, Richard Holbrooke denies that the U.S. seeks to sideline Afghanistan’s elected president, Hamid Karzai. But the handwriting is on the wall. After floundering around for 7 years, the U.S. and the west appear to be falling back on a failed Clinton-era plan to embrace the Taliban’s legitimacy. But if fixing Afghanistan – a country so recently believed to be open to a western democratic embrace – has proven too taxing for the west’s leadership – what can the Obama administration do to right the situation before the same old misinformed policy habits issue in a new wave of Islamic extremism?

The first major mistake, according to one well placed Afghan/American was Washington’s total deference to American companies whose control of the reconstruction process assured that the financial benefits accrued exclusively to foreign developers, contractors, and suppliers while leaving the local population and their leadership out of the development loop.

Over the last 7 years much of the aid that reached Afghanistan never got to the local level where it mattered and where it did, it was snatched up by warlords, put in power by Bush administration overseers. As free market ideologues, the Bush administration allowed international contractors free reign over reconstruction and did virtually nothing to coordinate western aid or distribute it fairly throughout Afghanistan. Instead, the virtuous cycle that reconstruction could have generated for the rural population with jobs and revenue quickly turned vicious, alienated the population, spurred corruption and undermined the new government’s legitimacy.

Aside from squandering its military advantage by turning away from Afghanistan to Iraq, the situation was turned from bad to worse when the Bush administration insisted on putting the “hated” warlords back into the new centralized government to compensate for its under-manned mission.

Now the Obama administration seeks to redress Bush era mistakes. But while Washington might dream that returning to a pre-9/11 strategy of splitting its “moderate” Taliban enemy from its “hard-core ideological” Taliban enemy might turn the tide, the chilling impact of a Taliban return will shut down any further local cooperation with the west.

Appearing on the scene as if by miracle in 1992, the Taliban’s purported mission of clearing the countryside of warlords and drug dealers was received warmly by Washington’s K street lobbyists. Painted by Pakistan’s Inter Services Intelligence Directorate (ISI) as an indigenous Afghan tribal force, the Taliban were actually a thinly disguised ISI strike-force paid for by a consortium of business interests.

The CIA’s former chief of the Near-East South-Asia Division in the Directorate of Operations, Charles Cogan today refers to them as “a wholly owned subsidiary of the ISI.” But former ISI Director General Hamid Gul claims his ISI also received help from Britain’s former High Commissioner to Pakistan, Sir Nicholas Barrington who “inducted both former royalists and erstwhile communists into the Taliban movement.”

For 8 years, the Clinton administration bought the idea of a “moderate” Taliban. But the very idea was a chimera, played skillfully by the ISI in a double game that saw Washington unwittingly support ISI’s interests while undermining its own.

Today, the Obama administration resumes where the Clinton administration left off, but if it really wants a fair and lasting solution for Afghanistan, it must begin by helping the Afghan people fulfill their democratic and progressive potential, and in doing so, it will help them lead this whole part of the Islamic world.

Covering a span of sixty years, the graphic novel Logicomix was inspired by the epic story of the quest for the Foundations of Mathematics.

This was a heroic intellectual adventure most of whose protagonists paid the price of knowledge with extreme personal suffering and even insanity. The book tells its tale in an engaging way, at the same time complex and accessible. It grounds the philosophical struggles on the undercurrent of personal emotional turmoil, as well as the momentous historical events and ideological battles which gave rise to them.

The role of narrator is given to the most eloquent and spirited of the story’s protagonists, the great logician, philosopher and pacifist Bertrand Russell. It is through his eyes that the plights of such great thinkers as Frege, Hilbert, Poincaré, Wittgenstein and Gödel come to life, and through his own passionate involvement in the quest that the various narrative strands come together.

Samuel R. Delany’s Dhalgren is—like Moby-Dick, Naked Lunch, or “Chocolate Rain”—an essential monument both to, and of, American craziness. It doesn’t just document our craziness, it documents our craziness crazily: 800 epic pages of gorgeous, profound, clumsy, rambling, violent, randy, visionary, goofy, postapocalyptic sci-fi prose poetry. The book is set in Bellona, a middle-American city struggling in the aftermath of an unspecified cataclysm. Phones and TVs are out; electricity is spotty; money is obsolete. Riots and fires have cut the population down to a thousand. Gangsters roam the streets hidden inside menacing holograms of dragons and griffins and giant praying mantises. The paper arrives every morning bearing arbitrary dates: 1837, 1984, 2022. Buildings burn, then repair themselves, then burn again. The smoke clears, occasionally, to reveal celestial impossibilities: two moons, a giant swollen sun. To top it off, this craziness trickles down to us through the consciousness of a character who is, himself, very likely crazy: a disoriented outsider who arrives in Bellona with no memory of his name, wearing only one sandal, and who proceeds to spend most of his time either having graphic sex with fellow refugees or writing inscrutable poems in a notebook—a notebook that also happens to contain actual passages of Dhalgren itself. The book forms a Finnegans Wake–style loop—its opening and closing sentences feed into one another—so the whole thing just keeps going and going forever. It’s like Gertrude Stein: Beyond Thunderdome. It seems to have been written by an insane person in a tantric blurt of automatic writing.

When I mention this to Delany, he is pleased. It is, he says, exactly the effect he was going for. And yet, he tells me, the actual writing process was deliberate and precise. “I wrote out hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of sentences at the top of notebook pages,” he remembers. “Then I would work my way down the page, revising the sentence, again and again. When I got to the bottom I’d copy the sentence out to see if I wanted it. Then I’d put them back together again. It was a very long, slow process.” It took him five years—not long by epic-novel standards, but a lifetime for an author who once wrote a book in eleven days to fund a trip to Europe.

In the 35 years since its publication, Dhalgren has been adored and reviled with roughly equal vigor. It has been cited as the downfall of science fiction (Philip K. Dick once called it “the worst trash I’ve ever read”), turned into a rock opera, dropped by its publisher, and reissued by others. These days, it seems to have settled into the groove of a cult classic. In a foreword in the current edition, William Gibson describes the book as “a literary singularity” and Delany as “the most remarkable prose stylist to have emerged from the culture of American science fiction.” Jonathan Lethem called it “the secret masterpiece, the city-book-labyrinth that has swallowed astonished readers alive.”

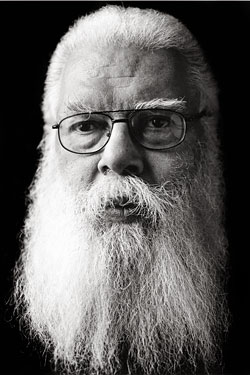

Delany, meanwhile, with his restless mind and his giant white cyberpunk-Santa beard, has become a science-fiction icon—a grandfatherly figure without any visible grandfatherly tendencies.

!SNIP!

This is a book about the emotional life of the ancient Romans. In particular, it is about the extremes of despair, desire, fascination, and envy and the ways in which these emotions organized the world and directed the actions of the ancient Romans.... I have written in an effort to address some of the darkest riddles of the Roman psyche, because I suspected that they were some of the riddles of my own life and perhaps of human life: the conjunctions of cruelty and tenderness, exaltation and degradation, asceticism and license, erethism and apathy, energy and ennui, as they were realized in a particular historical and sociological setting, the period of the civil wars and the establishment of the monarchy, roughly the first century BCE and the first two centuries CE.

...

We, in the late twentieth century, have a very small vocabulary to deal with the impossible, the intolerable, and the miraculous. But sometimes other cultures, quickened in a different time and space, can offer us words, images, and symbols to say something that our own culture has not the means to say. Perhaps this strange, ancient warrior culture can say something for us - even if it is not consoling.

I've owned a copy of Dhalgren since I was a teen and never read it. I have thought about it several times, though, and may several times more before I die.

“I wrote out hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of sentences at the top of notebook pages,” he remembers. “Then I would work my way down the page, revising the sentence, again and again. When I got to the bottom I’d copy the sentence out to see if I wanted it. Then I’d put them back together again. It was a very long, slow process.”

Users browsing this forum: No registered users and 8 guests