The Armenian Genocide

ROUBEN PAUL ADALIAN

Between the years 1915 and 1923 the Armenian population of Anatolia and historic West Armenia was eliminated. The Armenians had lived in the area for some 3000 years. Since the 11th century, when Turkish tribal armies prevailed over the Christian forces that were resisting their incursions, the Armenians had lived as subjects of various Turkish dynasties. The last and longest-lived of these dynasties were the Ottomans, who created a vast empire stretching from Eastern Europe to Western Asia and North Africa. To govern this immense country, the Ottomans imposed a strictly hierar- chical social system that subordinated non-Muslims as second-class sub- jects deprived of basic rights. In its waning days, with the empire in decline and territorially confined to the Middle East, the Ottoman leaders decided that the only way to save the Turkish state was to reduce the Christian pop- ulations. Beginning in April 1915, the Armenians of Anatolia were deported to Syria and the Armenian population of West Armenia was driven to Mesopotamia. Described euphemistically as a resettlement policy by the perpetrators, the deportations, in fact, constituted and resulted in genocide. In the end, after eight years of warfare and turmoil in the region, the Armenians had disappeared from their homeland.

Who Committed the Genocide?

In 1915 the Ottoman Empire was governed by a dictatorial triumvirate. Enver was Minister of War. Talaat was Minister of the Interior. Jemal was Minister of the Navy and military governor of Syria. All were members of

the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), called Unionists for short. They were known in the West as the Young Turks. They had started out as members of a clandestine political organization that staged a revolution in 1908, replaced the ruler of the country in 1909, and finally seized power by a coup in 1913 (Ramsaur, 1957; Zürcher, 1998; Charny, 1999).

When World War I started, the CUP exercised near total control in the government. Party functionaries had been appointed to posts all across the empire. Unionist cells had been organized in every major town and city. Unionist officers commanded virtually all of the Ottoman army. The cabinet was entirely beholden to the CUP. Key decisions were made by the triumvirs in consultation with their party ideologues and in conformity with overt and covert party objectives. As heads of government and leaders of the CUP, Enver, Talaat, and Jemal had at their disposal immense resources of power and an arsenal of formal and informal instruments of coercion (Libaridian, 1985, pp. 37–49).

Organized in reaction to the autocratic regime of the sultan Abdul- Hamid II (1876–1909), the Young Turks originally advocated a platform of constitutionalism, egalitarianism, and liberalism. They attributed the weakness of the Ottoman Empire to its retrograde system of government. They hoped to reform the state along the progressive and modernizing course of the Western European countries. However, after the revolution, they were surprised by the strength of conservative and reactionary forces in Ottoman society and were just as quickly disillusioned by the aggressive posture of the European powers, which vied with one another for influence in the Ottoman Empire. Their realization that the problems of the Ottoman Empire were systemic and endemic became the source of their own retrenchment and growing intransigence. Also, suspicious of British, French, and Russian colonialist designs, defeated in war by the Italians, and challenged militarily by neighboring Greece, Serbia, and Bulgaria (countries that were formerly subject states of the empire), the Young Turks increasingly looked toward Germany as an ally and as the model nation-state to emulate. By 1913, the advocates of liberalism had lost out to radicals in the party who promoted a program of forcible Turkification.

By the time the first shots of the war were fired in August 1914, the CUP had become a dictatorial, xenophobic, intolerant clique intent on pursuing a policy of racial exclusivity. Emboldened by their alliance with Imperial Germany, the CUP also prepared to embark on a parallel course of militarism. German war materiel poured into the country, and Turkish officers trained at military schools in Germany. German army and navy officers drilled the Ottoman forces, drew their battle plans, built fortifications, and, when war erupted, stayed on as advisors whose influence

often exceeded that of the local commanders (Sachar, 1969, pp. 5–31; Trumpener, 1968, pp. 62–107; Dinkel, 1991, pp. 77–133).

Because of the preponderance of the Germans in Ottoman military affairs, the lurking question of the degree of their involvement in either advising or permitting the deportation of the Armenians has been asked many times (Dadrian, 1996). Ultimate responsibility for the Armenian genocide, however, rests with those who considered and took the decision to deport and massacre the Armenian population of the Ottoman Empire. It also rests with those who implemented the policy of the central government and, finally, with those who personally carried out the acts that extinguished Armenian society in its birthplace. In this equation, the largest share of responsibility falls on the members of the Committee of Union and Progress. At every level of the operation against the Armenians, party functionaries relayed, received, and enforced the orders of the government. The state’s responsibility to protect its citizens was disregarded by the CUP. The Ministries of the Interior and of War were charged with the task of expelling the Armenians from their homes and driving them into the Syrian desert (Dadrian, 1986). The army detailed soldiers and officers to oversee the deportation process (Great Britain, 1916, pp. 637–53; Ternon, 1981, pp. 22–39). Killing units were organized to slaughter the Armenians (Dadrian, 1989, pp. 274–77). By withholding from them the protection of the state and by exposing them to all the vagaries of nature, the Young Turk government also disposed of large numbers of Armenians through starvation (Ternon, 1981, pp. 249–60). In the absence of even minimal sanitation, let alone health care, epidemics broke out in the concentration camps and contributed to the death toll.

How Was the Genocide Committed?

The genocide of the Armenians involved a three-part plan conceived with secrecy and deliberation and implemented with organization and efficiency. The plan consisted of deportation, execution, and starvation. Each part of the plan had its specific purpose.

The most thoroughly implemented part of the plan was the deportation of the Armenian population. The Armenians in historic Armenia in the east, in Anatolia to the west, and even in European Turkey were all driven from their homes. Beginning in April 1915 and continuing through the summer and fall, the vast majority of the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire were deported. Upon the orders of the Ottoman government, often with only three days’ notice, village after village and town after town was emptied of its Armenian inhabitants.

Many were moved by train (Bryce, 1916, pp. 407–63). Some relied on horse-drawn wagons. A few farmers took their mules and were able to carry some belongings part of the way. Most Armenians walked. As more

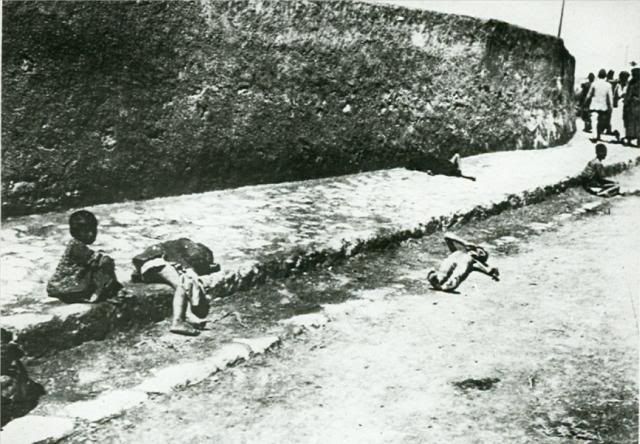

and more people were displaced, long convoys of deportees, comprised mostly of women and children, formed along the roads of Anatolia and Armenia, all headed in one direction, south to the Syrian desert. Many never made it that far. Only a quarter of all deportees survived the hundreds of miles and weeks of walking. Exhaustion, exposure, and fright took a heavy toll especially on the old and the young (Hairapetian, 1984, pp. 41–145).

The Ottoman government had made no provisions for the feeding and the housing of the hundreds of thousands of Armenian deportees on the road (Bryce, 1916, pp. 545–69). Indeed, local authorities went to great length to make travel an ordeal from which there was little chance of survival (Davis, 1989, pp. 69–70). At every turn, Armenians were robbed of their possessions, had their loved ones held at ransom, and even had their clothing taken off their backs. In some areas, Kurdish horsemen given to marauding and kidnapping were let loose upon the helpless caravans of deportees (Hairapetian, 1984, p. 96; Kloian, 1985, p.

. Apart from the sheer bedlam of their raids and the killing that accompanied it, they carried away the goods they snatched and frequently seized Armenian children and women.

The deportations were not intended to be an orderly relocation process (Walker, 1980, pp. 227–30). They were meant to drive the Armenians into the open and expose them to every conceivable abuse (Hovannisian, 1967, pp. 50–51) At remote sites along the routes traversed by the convoys of deportees, the killing units slaughtered the Armenians with sword and bayonet (Dadrian, 1989, p. 272; Walker, 1980, p. 213). In a random frenzy of butchering, they cut down persons of all ages and of both genders. These periodic attacks upon the unarmed and starving Armenians continued until they reached the Syrian desert.

To minimize resistance to the deportations, the Ottoman government had taken precautionary measures. The most lethal of these measures consisted of the execution of the able-bodied men in the Armenian population. The first group in Armenian society targeted for collective execution were the men conscripted into the Turkish armies. Upon the instruction of the War Ministry, these men were disarmed, forced into labor battalions, and either worked to death or outright murdered (Morgenthau, 1918, p. 302; Kuper, 1986, pp. 46–7; Sachar, 1969, p. 98).

Subsequently, the older males who had stayed behind to till the fields and run the stores were summoned by the government and ordered to prepare themselves for removal from their places of habitation. Virtually all the men turned themselves over without an inkling that their government contemplated their murder. They were immediately imprisoned, many were tortured, and all of them were taken away, sometimes in chains, and felled in mass executions (Bryce, 1916, pp. 640–41).

To assure the complete subservience of the Armenian people to the government’s deportation edicts and to eliminate the possibility of protestation, prominent leaders were specially selected for swift excision from their communities (Davis, 1989, p. 51). Although the wholesale measures against the Armenians were already in the process of implementation by late April, the symbolic beginning of the Armenian genocide is dated the evening of April 24, 1915. That night, the most gifted men of letters, the most notable jurists, the most respected educators, and many others, including high-ranking clergy, were summarily arrested in Constantinople, the capital of the Ottoman Empire, sent to the interior, and many were never heard from again (Ternon, 1981, pp. 216–19).

The Armenians were brought to the Syrian desert for their final expiration (Walker, 1980, pp. 227–30). Tens of thousands died from exposure to the scorching heat of the summer days and the cold of the night in the open. Men and women dying of thirst were shot for approaching the Euphrates River. Women were stripped naked, abused, and murdered. Others despairing of their fate threw themselves into the river and drowned. Mothers gave their children away to Arab Bedouins to spare them from certain death. The killing units completed their task at a place called Deir el-Zor. In this final carnage, children were smashed against rocks, women were torn apart with swords, men were mutilated, others were thrown into flames alive. Every cruelty was inflicted on the remnants of the Armenian people.

Why Was the Genocide Committed?

The Armenian genocide was committed to solve the “Armenian Question” in the Ottoman Empire. There were, at the very least, five basic reasons for the emergence of this so-called question. The first had to do with the decline of the Ottoman Empire and the internal demographic and economic pressures created upon the non-Muslim minority communities that began to experience ever-increasing and violent competition for the land and resources they historically controlled. The government’s failure to guarantee security of life and property led the Armenians to seek internal reforms that would improve their living conditions. These demands only invited resistance and intransigence from the government, which convinced many Armenians that the Ottoman regime was not interested in providing them the protection they needed and the civil rights they desired (Nal- bandian, 1963, pp. 67–89).

Second, Great Power diplomacy that offered the hope of redressing the injustices and inequities of the Ottoman system proved inadequate to the task. The greater interest in maintaining the balance of power in Europe only resulted in half-hearted measures at humanitarian intervention in response to crises and atrocities. As the Armenians turned to the European

powers in order to invite attention to their plight, the Ottomans only grew more suspicious of the intentions of the Armenians. Thus, the appeal of the Armenians to the Christian countries of Europe was viewed as seditious by the Ottomans. On earlier occasions European powers had exploited the tensions in Ottoman society to intervene on behalf of Christian populations. With the passage of time, the Ottomans became more resolved to prevent the recurrence of such intervention by quickly and violently suppressing expressions of social and political discontent (Dadrian, 1989, pp. 242–55; Dadrian, 1995, 61–97).

Third, the military weakness of the Ottoman Empire left it exposed to external threats and therefore made it prone to resorting to brutality as a method of containing domestic dissent, especially with disaffected non- Muslim minorities. In fact, a cycle of escalating violence against the Armenians had set in by the late 1800s (Dadrian, 1989, pp. 232–42).

Fourth, the reform measures introduced in the 19th century to moder- nize the Turkish state had initially encouraged increased expectations among Armenians that better government and even representation were imminent possibilities. The periodic massacre of large numbers of Armenians, however, undermined the confidence of the community in its government and in the prevailing international order. This disaffection became the source of a growing Armenian national consciousness and resulted in the formation of political organizations seeking emancipation from lawlessness and discrimination.

Last, the rapid modernization experienced by the Armenians, who were more open to European concepts of progress through education than the rest of the population, only registered resentment among the Muslims of the Ottoman Empire who saw the interests of Armenians more in alignment with countries they regarded as infidel than with the state ruling over them.

By the early 20th century, the Ottomans had been forced out of southeastern Europe. Having relinquished the mostly Christian and Slavic regions of the Balkans whence the early Ottomans had created their empire, the Young Turks sought to restore the empire on new foundations. They found their justification in the concepts of Turkism and Pan-Turan- ism. Turkism altered Ottoman self-perceptions from a religious to a national identity by emphasizing the ethnicity of the Turks of Anatolia to the exclusion of other populations and promoted the idea that the region should be the exclusive domain of the Turkish nation. Pan-Turanism advanced the idea of conquering lands stretching into Central Asia inhabited by other Turkic-speaking peoples. Many of these Turkic peoples were living under Russian rule, and the Young Turks believed that the advancing Ottoman armies would be received as liberators (Walker, 1980,

pp. 189–91). The Pan-Turanian goal was to unify all the Turkic peoples into a single empire led by the Ottoman Turks (Parla, 1985).

In this formulation, the Armenians presented an ethno-religious anomaly. They were an indigenous Christian people of the Middle East who, despite more than 14 centuries of Muslim domination, had avoided Islamification. When the CUP began to implement its policy of Turkification, the Armenians resisted the CUP plans. For example, the Armenians had worked hard to build up the infrastructure of their communities, including an extensive network of elementary and secondary schools. Through education, they hoped to preserve their culture and identity and to obtain participation in the government. The new emphasis on Turkism and the heightened suspicion of the subject nationalities was warning enough for the Armenians to redouble their effort to gain a say in at least the governance of regions with a heavy Armenian concentration (Libaridian, 1987, pp. 219–23).

In the increasing tension between the assimilationist policies of the Young Turk government and Armenian hopes for administrative reforms and aspirations for a measure of local self-government, the coincidence of resistance to Unionist policies and the beginning of World War I proved fatal for the Armenians. As the German forces were prevailing against Russia in Europe, a second front in Asia seemed to guarantee success for the Ottomans. Confident of their strength and witness to the early military victories of the German army, the Young Turks chose to enter the war. They believed that the great conflict among the imperial powers of Europe offered the Ottoman Empire an opportunity to regain a position of dominance in the region.

The war placed the Armenians in an extremely precarious situation. Tragically for them, their difficulties with the Young Turk regime were compounded by the fact that this second front against Russia would be fought in the very lands of historic Armenia where the bulk of the Armenian population lived. Straddled on both sides of the Russian–Turkish border, their homeland was turned into a battlefield. Long chafing from the exploitation of Muslim overlords, the Armenians had welcomed the Russians into Transcaucasia. After nearly a century of relative peace and prosperous existence under Russian administration, the prospect of falling under the rule of the Ottomans was unthinkable for the Armenians living in Russia. While thousands of Armenian conscripts were serving on the Russian front in the war against Germany, many others volunteered to fight the Ottomans.

The fate of the Armenians was sealed in early 1915 with the defeat of the Ottoman offensive into Russian territory. The Russians not only stopped the Ottoman advance but slowly moved into Ottoman territory. The failure of the campaign was principally the fault of Enver, the Minister of War, who had taken personal command of the eastern front and chosen to fight a major battle in the dead of winter in rugged and snowbound terrain. With his ambitions dashed, this would-be conqueror and self- styled liberator exacted vengeance from the Armenian population.

Instead of accepting responsibility for their ill-conceived invasion plans and the consequential defeat of their armies, the Young Turks placed the blame on the Armenians by accusing them of collaboration with the enemy (Morgenthau, 1918, pp. 293–300). Charging the entire Armenian population with treason and sedition, they decided to kill the innocent for the actions of those who had chosen to put a stop to their planned conquests. That was the reason, at least, given by the Minister of the Interior when asked about the CUP policy of deporting the Armenians (Morgenthau, 1918, p. 327; Trumpener, 1968, pp. 207–10).

The war, in effect, provided the opportunity to implement the Turkification of the Ottoman Empire by methods that exceeded legislation, intimidation, and expropriation. Under the cover of war, with no obligation to uphold international agreements, and in an atmosphere of heightened tensions, the Unionists found their justification and opportunity to resort to extreme measures. The Turkish state now could be created internally. With the Armenians eradicated, one less racial grouping would be living on Ottoman territory. One less disenchanted group would have to be tolerated. The problems with the Armenians would be automatically resolved by eliminating the Armenians. In a country of 20 million people, the Armenians constituted only about 10 percent of the population. It was easily within the reach of the Ottoman government to displace and kill that many people.

For all the historical, political, and military reasons that may be cited to explain the Young Turk policy of destroying the Armenians, it must be understood that ultimately the decision to commit genocide was taken consciously. Genocide is not explained by circumstance. Mass murder is an act deliberately conceived. Decision-makers can always exercise other options in dealing with serious conflicts. The real cause of genocide lies in the self-licensing of those in charge of government with irresponsibility toward human life and amorality in the conception of their social policies. Genocide is the fulfillment of absolute tyranny. In the new social order conceived by the Young Turks, there was no room for the Armenians. They had become that excess population of which tyrants are prone to dispose.

Who Were the Victims?

The Armenians were an ancient people who from the first millennium B.C. lived in a mountainous plateau in Asia Minor, a country to which they gave their name. This was their homeland. The area was absorbed as the eastern provinces of the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century. Two thousand years

earlier the Armenians had formed one of the more durable states in the region. A series of monarchical dynasties and princely families had been at the head of the Armenian nation. Early in the fourth century, the king of Armenia accepted Christianity, making his country the first to formally rec- ognize the new faith. Armenians developed their own culture and spoke a unique language. A distinct alphabet, a native poetry, original folk music, an authentic architectural style, and centuries-old traditions characterized their separate civilization (Lang, 1970; Lang, 1981; Bournoutian, 2002; Adalian, 2002).

The remoteness of Armenia from the centers of urban life in the ancient world kept the Armenians on the periphery of the empires of antiquity. Their distinctiveness was reinforced by the mountainous country and the harsh and long winters, which discouraged new settlers. Their own armies fought off many invaders; but through the course of the centuries, Armenia proved too small a country to withstand the continued menace of outside aggression. The strength of its armies was sapped. Its leaders were defeated in battle, and its kings were exiled and never returned. Increasingly exposed to invasions, the Armenians finally suc- cumbed to the occupying forces of a new people that emerged from the east.

Persians, Greeks, Romans, Arabs, Byzantines, and Mongols each in turn lorded over the Armenians; however, only the Turks made permanent settlements in Armenia. The seeds of a mortal conflict were planted as the Turks grew in number and periodically displaced the Armenians. Beginning from the 11th century, towns, cities, and sometimes entire districts of Armenia were abandoned by the Armenians as they fled from the exactions of their new rulers. Unlike all the other conquerors of Armenia, the Turks never left. In time, Armenia became Turkey. The genocide of 1915 brought to a brutal culmination a thousand-year struggle of the Armenian people to hold on to their homeland and of the Turks to take it away from them.

The Ottoman Turks, who built an empire around the city of Constantinople after conquering it in 1453, and who eventually seized the areas of historic Armenia, developed a hierarchically organized society. Non-Muslims were relegated to second-class status and were subjected to discriminatory laws. The constant pressure on the Armenian population resulted in the further dispersion of the Armenians. Yet, despite the difficulties they endured and the disadvantages they faced, Armenian communities throughout the cities of the Ottoman Empire attained a tolerable living standard. By the 19th century a prosperous middle class emerged that became the envy of the Turkish population and a source of distrust for the Ottoman government (Barsoumian, 1982, pp. 171–84).

As the Armenians recovered their national confidence, they increased their demands for reforms in Armenia, where conditions continued to deteriorate. The government, however, was opposed to the idea of introducing measures and policies that would have enhanced the progress of an industrious minority that already managed a sizable portion of Ottoman commerce and industry. This reluctance only contributed to the alienation of the Armenians from the Ottoman regime. The more the Armenians complained, objected, and dissented, the more the Ottoman government grew annoyed, resistant, and impatient. By refusing to introduce significant reform in its autocratic form of government and to restrain the arbitariness of local administration, the Ottoman rulers placed the Armenian and the Turkish peoples on a collision course (Astourian, 1992, 1998).

Who Was Involved in the Genocide?

The Armenian genocide was organized in secret but carried out in the open (Dadrian, 1989, p. 299; 1991, p. 558). The public proclamations ordering the removal and departure of the Armenians from their homes alerted all of Ottoman society that its government had chosen a course of action specifi- cally targeting this one minority for unusual treatment. At no time throughout its existence had the Ottoman state taken such a step against an entire population. The manner in which the deportations were carried out notified the rest of society that the measures were intended to yield a per- manent outcome.

A policy directed against a select population requires the agencies of government to organize, command, implement, and complete the separation and isolation of the group from the rest of society. When the measures affect a population spread across a vast stretch of territory, it cannot be a matter of accident, or coincidence, that persons of the same ethnic background become the object of mistreatment.

Although the decision to proceed with genocide was taken by the CUP, the entire Ottoman state became implicated in its implementation. First, cabinet decisions were taken to deport and massacre the Armenians (Dadrian, 1989, pp. 265–67). Disguised as a relocation policy, their purpose was understood by all concerned. Second, the Ottoman parliament avowedly enacted legislation legalizing the decisions of the cabinet (Dadrian, 1989, pp. 267–74). Third, the Ministry of the Interior was delegated the responsibility of overseeing the displacement, deportation, and relocation process. This Ministry, in turn, instructed local authorities on procedure, the timing of deportation, and the routing of the convoys of exiles (Dadrian, 1986, pp. 326–28). The Ministry of War was charged with the disarming of the Armenian population, the posting of officers and soldiers to herd the deportees into the desert, and the

execution of the Armenian conscripts. The agencies in charge of transport also were inducted into service. To expedite the transfer of the Armenians of western Anatolia, the deportees were loaded on cattle cars and shipped en masse to points east by train. The telegraph service encoded and decoded the orders of the ministers and governors. The governors of the provinces relayed the orders to the district governors, who in turn entrusted the local authorities, courts, and constabularies to proceed with instructions. The chain of command that put the Armenian genocide into motion joined every link in the administration of the Ottoman state.

Orders, however, were not obeyed uniformly. A few governors downright refused to deport the Armenians in their districts (Dadrian, 1986, pp. 326–27). Aware that some government personnel might be reluctant to sign the death warrant of the Armenian people, the CUP had made provisions to enforce its will on the entire corps of Ottoman officials. Young Turk Party members were entrusted by the central leaders with extraordinary power in situations requiring the disciplining of local authority. Disobedient governors were removed from their posts, and CUP partisans with a more reliable record were assigned to carry out the state’s policies in these districts. Frequently, the most notorious among the latter happened to be army officers who were also ideological adherents of the CUP, a combination that gave them complete license to satisfy — at the expense of the Armenians — their every whim and that of the men under their command (Dadrian, 1986, pp. 311–59).

To implement the various aspects of its policy, the CUP cabinet had to go so far as to establish new agencies. One of these was a secret extra-legal body called the Special Organization. Its mission was organized mass murder (Dadrian, 1989, pp. 274–77). It was mainly composed of convicted criminals released from prisons, who were divided into units stationed at critical sites along the deportation routes and near the concentration camps in Syria. Their assignment consisted solely of reducing the number of the Armenians by carrying out massacres. Sparing bullets, which were needed for the war effort, the slaughter of the Armenians frequently was carried out with medieval weaponry: scimitars and daggers. The physical proximity with which the butchering went on left a terrifying image of the Turk among those who happened to survive an attack by squads of the Special Organization.

Additionally, the government set up a Commission on Immigrants, whose stated purpose was to facilitate “the resettlement” process. In fact, the commission served as an on-site committee to report on the progress of the destruction of the Armenians as they were further and further removed from the inhabitable regions of Anatolia and Syria. As for the Commission on Abandoned Goods, which impounded, logged, and auctioned off Armenian possessions, this was the government’s method of

disposing the immovable property of the Armenians by means that rewarded its supporters. Generally, the local CUP officials pocketed the profit. It is not known what sums might have been transferred to party coffers (Baghdjian, 1987, pp. 64–87).

The CUP orchestrated a much wider system of rewards in order to obtain the consent of the Turkish population (Baghdjian, 1987, pp. 121–71). By implicating large numbers of people in the illegal methods of acquisition, the Young Turk government purchased the silence and cooperation of the populace. Many enriched themselves by misappropriating the forcibly aban- doned properties of the Armenians. There was easy gain in plunder.

The same impulse motivated the Special Organization and the Kurdish tribesmen, who were given license to raid the convoys of deportees. In their case, the booty included human beings as well. It was a form of enslavement limited to younger boys and girls, who, separated from their kinsmen, would be converted to Islam and either Kurdified or Turkified in language and custom. Lastly, the public auction of Armenian girls revived a form of human bondage that was, for the most part, erased elsewhere in the world. The auctioneer made money. The purchaser had a slave servant and a harem woman added to his household. This kind of brutalization scarred countless Armenian women. Many, incapable of bearing the shame of giving birth out of wedlock to children conceived from rape and abuse by their Kurdish and Turkish owners, chose to forgo Armenian society after the war and remained with their Muslim families. Some were rescued and a few escaped, some taking their children with them, while others, fearing reprisal, abandoned them. Some Armenian women taken into harems against their will were often tattooed on their arms, chest, or face, as signs of their being owned and as a way to discourage escape (Sanasarian, 1989, pp. 449–61).

The gender, age, occupational, and regional differences in the treatment of the Armenians reflected the varying operative value systems prevailing in Ottoman society. The Young Turk ideologues in Constantinople conceived and implemented genocide, a total destruction of Armenian society. Military officers and soldiers regarded the policy as a security measure. Others in Ottoman society saw it a convenient way of ridding themselves of effective economic competitors, not to mention creditors. Others justified the slaughter of the Armenians as religious duty called upon by the concept of jihad, or warfare against infidels or nonbelievers in Islam. All essentially aimed at eliminating the Armenian male population. Traditional society in the Middle East still looked upon women and children as chattel, persons lacking political personality and of transmutable ethnic identity. The cultural values of children and of females could be erased or reprogrammed. Genetic continuity was a male proposition. For many, but not the CUP, the annihilation of Armenian

TheArmenianGenocide• 65 males would have been sufficient to block or impede the perpetuation of

the Armenian people (Davis, 1989, pp. 54–63).

What Were the Outstanding Historical Forces and Trends at Work that Led to the Genocide?

The Armenian genocide was the result of the intensifying differences between two societies inhabiting the territories of a single state. One society was dominant, the other subordinate; one Muslim, the other Christian; one in the majority, the other in the minority. At its source, the conflict stemmed from two divergent views of the world. The Turks had established their state as a world empire. They had always ruled over lands and peoples they conquered. The receding of their empire from its far-flung provinces challenged their image of themselves. Virtually undefeated in war before 1700, in the 18th and 19th centuries the Ottomans lost battle after battle as their once-mighty armies were no longer a match for the modern tactics and weaponry of the armies of the European states. New empires taking form on the European continent began to carve away Ottoman territory. France, England, Austria, and Russia, each in turn, imposed its demands on the weakening Turkish state. By the second half of the 19th century, how- ever, these European powers, soon joined by a Germany unified by Prussian arms, balanced out each other in their competition for global influence.

A new type of challenge arose to force the Ottomans into retreating further. Whereas the Ottomans were in part successful in checking the territorial aggrandizement of their neighbors by relying on the balance-of- power system, the rise of nationalist movements among the subject peoples of the empire posed a different predicament. As imperial states are wont to do, the Ottomans resorted to brutal methods of suppressing national liberation and other separatist movements. The response of the Ottomans to the uprisings in Greece, Serbia, Bulgaria, and elsewhere was mass action against the affected population. These tactics only invited European intervention, and the settlement often resulted in the formation of a small autonomous state from a former Ottoman province as a way of providing a national territory to the subject people.

Unlike the Greeks, Serbians, or Bulgarians, the case of the Armenians was more complicated. They had long been ruled by the Turks, and by the early 20th century they were widely dispersed. In historic Armenia, the Armenians formed a majority of the population only in certain districts. This was due to the fact that a substantial Kurdish and Turkish population lived in these lands. When the Armenians also began to aspire for a national home, the Ottomans regarded it a far more serious threat than earlier and similar nationalist movements, for they had come to regard historic Armenia as part of their permanent patrimony.

The fracturing of the status of the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire has a complicated diplomatic history to it. The Russo–Turkish War of 1877–1878 was concluded with the signing of the Treaty of San Stefano, which ceded the Russians considerable Ottoman territory. The European powers vehemently opposed the sudden expansion of Russian influence in the Balkans and the Middle East, and compelled the Russian monarch to agree to terms more favorable to the Ottomans in the Treaty of Berlin. All the European powers became signatories to this treaty. One of the terms in the Treaty of Berlin promised reforms in the so-called Armenian provinces of the Ottoman Empire. Armenians saw hope in this treaty. They thought an international covenant would have greater force in compelling the Ottomans to consider reorganizing the ramshackle administration of their remote provinces. When the European powers failed to persist in requiring the Ottoman sultan to abide by the terms of the treaty, the Armenians faced a rude awakening. Not only were they disappointed with a govern- ment that did not keep its promises, but they also realized that the powers had little interest in devoting time to the problems of the Armenians (Hovanissian, 1986c, pp. 19–41).

The fundamental issue separating Armenians and Ottomans was their diametrically opposed definitions of equality. Empires are inherently unequal systems. They divide the people into the rulers and the ruled. The Islamic empires, including the Ottoman state, compounded this system of inequality because the legal and judicial precepts of Islam also subordinated non-Muslim subjects to second-class status. Not only was the Ottoman system unequal, Ottoman society was unaccustomed to a concept of equality among men irrespective of their racial or religious background.

Although laws were issued accepting the principle of equality among the various confessional groups in the Ottoman Empire, the Muslim populace remained unconvinced that they should accept these secular ideas. Instead of leading to a new adjustment in Ottoman society, these laws became the source of consternation among Muslims, who believed these notions upset the established social order. The hierarchy of faiths had never been reconsidered in an Islamic society since the religion was founded in the seventh century. On the contrary, to the Muslims, the combination of European states sponsoring reforms on behalf of Christian minorities and these peoples, in turn, aspiring for equal treatment under the law appeared to be a bid by the subject Christians for power over the Muslims (Dadrian, 1999, pp. 5–26).

Islamic law disenfranchised Christians and Jews. Their testimony was inadmissible in court, thus frequently denying them fair treatment by the justice system. Christians and Jews were also required to pay additional levies, such as a poll tax. For a peasantry eking out a living on the farm, the

extra taxes often became an obligation that could not be met in a difficult year. The end result was commonly foreclosure and eviction. Disallowed from bearing arms, non-Muslims had no means for self-defense. They could protect neither their persons and families nor their properties. In certain places, dress codes restricting types of fabric used by the Christians helped differentiate them from the population at large, exposing them to further intimidation. At times a language restriction meant speaking a language other than Turkish at the risk of having one’s tongue cut out. As a result, in many areas of the Ottoman Empire Armenians had lost the use of their native language (Ye’or, 1985, pp. 51–77).

These disabilities would have been impairing under normal circum- stances. In areas closer to the capital, competent governors oversaw the administration of the provinces, and Armenians flocked to these safer parts of the empire. In the remoter provinces, such as the areas of historic Armenia, the hardships faced by the ordinary people were insurmount- able. Avaricious officials exacted legal and illegal taxes. The justice system was hopelessly rigged. The maintenance of law and order was entrusted to men who only saw in their positions the opportunity for reckless exploitation. Extortion and bribery were the custom. In the countryside, the army demanded quartering in the houses of the Armenian peasants, which made their families hostages in their own homes. Unable to defend themselves, these people were also at the mercy of tribesmen, who descended upon their villages and carried off goods, flocks, and women. With no recourse left, Armenians were being driven to desperation.

The disappointment over the failure of the European powers to intervene effectively, combined with the dismay over the delays of the Ottoman government, continued to fuel the crisis in the Armenian provinces. Some Armenians decided to take matters into their own hands. In certain parts of Armenia, during the 1880s and 1890s, individuals began arming themselves and forming bands that, for instance, resisted Kurdish incursions on Armenian villages. Others joined political organizations advocating revolutionary changes at all levels of society. They demanded equal treatment, an adequate justice system, fair taxation, and the appointment of officials prepared to act responsibly (Nalbandian, 1963, pp. 167–68).

The Ottoman authorities refused to consider the demands. In response to the rise of nationalist sentiment among the subject peoples, and other internal and external security concerns, the Ottoman sultans had been striving to centralize power in their hands and had been creating a modernized bureaucracy that would help expand the authority of the government in all areas of Ottoman society. Among the measures introduced by the sultan Abdul-Hamid was a secret police and irregular cavalry regiments, called in his honor the Hamidiye corps, to act both as border guards and local gendarmerie. They became his instrument for suppression. In 1894, at a time of increasing tension between the Armenian population and the Ottoman government, which also coincided with increased political activism by Armenians and inadequate efforts at intervention by some of the European powers, the sultan unleashed his forces. Over the next three years, a series of massacres were staged throughout Armenia. Anywhere between 100,000 and 300,000 persons were killed, others were wounded, robbed, thrown out of their homes, or kidnapped. Many also fled the country (Bliss, 1982, pp. 368–501; Greene, 1896, pp. 185–242; Walker, 1980, pp. 156–73).

The Armenian massacres of 1894–1896 made headline news around the world. They engendered international awareness of the plight of the Armenians, and their horrendous treatment by the sultan’s regiments resulted in condemnation of the Ottoman system (Nassibian, 1984, pp. 33–57). The European powers were compelled by public clamor in their own countries to urge the sultan to show restraint. The massacres were halted, but nothing was done to punish the perpetrators or to remedy the damage.

This cycle of violence against the Armenian population repeated itself in 1909 in the province of Adana, a region along the Mediterranean coast densely settled by Armenians, where again the Armenian neighborhoods were raided and burned. The estimate on the number of victims runs between 10,000 and 30,000 (Walker, 1980, pp. 182–88). The Adana massacre coincided with an event known as the Hamidian counter-revolution. The Young Turks had achieved political prominence by staging a military revolution in 1908. They had compelled the sultan, Abdul-Hamid, to restore the Ottoman Constitution, which he himself had issued in 1876 and soon after suspended. The sultan was suspected of having plotted to recover his autocratic powers by dislodging the Young Turks from Constantinople. In the ensuing climate of tension and suspicion the Adana massacre erupted.

The Young Turks blamed the Hamidian supporters of igniting strife in order to embarrass the progressive forces in Ottoman society, but the Young Turks themselves were also implicated in the atrocities. It augured badly for the Armenians. The Adana massacre demonstrated that even in a power struggle within Turkish society, the Armenians could be scapegoated by the disaffected and made the object of violence. In this context, Enver’s embarrassment at his defeat in early 1915 and the government’s casting of blame on the Armenians had a precedent. In this chain of events, the genocide of 1915 was the final, and mortal, blow dealt the Armenians by their Ottoman masters (Libaridian, 1987, pp. 203–35).

TheArmenianGenocide• 69 What Was the Long-Range Impact of the Genocide on the Victim

Group?

The Armenians in the Ottoman Empire never achieved equality and were never guaranteed security of life and property. They entered the Ottoman Empire as a subject people and left it as a murdered or exiled population. It is estimated that the Armenian genocide resulted in the death of over one and a half million people. Beyond the demographic demise of the Arme- nians in the larger part of historic Armenia, the Armenian genocide brought to a conclusion the transfer of the Armenian homeland to the Turkish people. The Young Turks had planned not only to deprive the Armenians of life and property, but also conspired to deny to the Armenians the possibility of ever recovering their dignity and liberty in their own country.

Whole communities and towns were wiped off the map. The massive loss in population threatened the very existence of the Armenian people. Hardly a family was left intact. The survivors consisted mostly of orphans, widows, and widowers. The Armenian nation was saved only through the direct delivery of American relief aid to the “starving Armenians.” Millions of dollars were collected in the United States to feed and house the destitute Armenians, both in the Middle East and in Russia, where tens of thousands took refuge. Hundreds of thousands eventually received some sort of aid, be it food, clothing, shelter, employment, resettlement, or emigration to the United States and elsewhere.

The tremendous difficulty faced by the Armenians in recovering from the devastating impact of the genocide had much to do with the fact that they, as a collectivity, had been robbed of all their wealth. They were forced to abandon their fixed assets. They received neither compensation nor reparations. As deportees, Armenians were unable to carry with them anything beside some clothing or bedding. All their businesses were lost. All their farms were left untended. Schools, churches, hospitals, orphanages, monasteries, graveyards, and other communal holdings became Turkish state property. The genocide left the Armenians penniless.

Those who survived and returned to reclaim their homes and properties after the end of World War I were driven out again by the Nationalist Turks who had risen to power in Turkey (Kerr, 1973, pp. 214–54). For the Armenians, the only choice was reconciliation with their status as exiles and resettlement wherever they could find a means of earning a living. With the inability to recongregate as a people in their homeland, the Armenians dispersed to the four corners of the world (Adalian, 1989, pp. 81–114; Adalian, 2002).

Lastly, the genocide shattered the historic bond of the Armenian people with their homeland. The record of their millennial existence in that country turned to dust. Libraries, archives, registries, the entire recorded memory of the Armenians as accumulated in their country was lost for all

time (Adalian, 1999a).

What Were the Responses to this Particular Genocide?

At the time, the horror story of the Armenian genocide shocked the world. The Allies threatened to hold the Young Turks responsible for the massacres (Dadrian, 1989, p. 262), but the warning had no effect. The Allies were pre- occupied with the war in Europe and did not commit resources to deliver the Armenians from their fate. Locally, however, humanitarian intervention by individual Turks, Kurds, and Arabs saved many lives (Hovannisian, 1992, pp. 173–207). While some Turks robbed their Armenian neighbors, others helped by hiding them in safe dwellings. While some Kurds willingly participated in the massacres, others guided groups of Armenians through the mountain passes to refuge in Russian territory. And while some Arabs only saw the Armenians as hopeless victims, others shared their food.

Among the first people to see the deplorable condition of the mass of the Armenians were the American missionaries and diplomats stationed in Turkey. Their appeals to their government, the religious institutions in the United States, and the general public were the earliest of the active responses to the predicament of genocide. They strove to deliver aid even during the war (Sachar, 1969, p. 343; Winter, 2003).

After the war, the European nations were little disposed to help the Armenians, as they themselves were trying to recover from their losses. Nevertheless, Britain and France, which had occupied Ottoman territory in the Middle East, were strongly positioned to influence the political outcome in the region, but neither chose to do so on behalf of the Armenians. Their interest in retaining control of these lands also conflicted with the wider goals of Woodrow Wilson in establishing a stable world order. The American president’s laudable policies were welcomed by the peoples of Europe and Asia, such as the Poles, Czechs, Arabs, and Indians, who saw in his principles for international reconciliation the possibility of attaining their national independence. He too, however, was unable to deliver more than words. The United States Congress was disinclined to involve America in foreign lands. Consequently, many territorial issues were solved through the pure exercise of might. Diplomacy had little chance of extending help to the Armenian refugees.

For the Turks, the failure of diplomacy provided an opportunity to regroup under new leadership and to begin their own national effort at building a new state upon the ruins of the Ottoman Empire. With Mustafa Kemal at their head, the Nationalist Turks forged a new government and secured the boundaries of modern-day Turkey. Their policy of national consolidation excluded despised minorities (Dadrian, 1989, pp. 327–33). The Armenians, the weakest element, headed the list. By 1923, when the

Republic of Turkey was formally recognized as a sovereign state, the Arme- nians remaining in the territories of that state, with the exception of those in Constantinople, had been driven out. For many survivors of the depor- tations who had returned to their former homes, this was their second expulsion (Kinross, 1964, p. 235).

Before the Turkish borders were finally sealed and the Armenians conclusively denied the right to their former homes, the absence of moral resolve in Turkish governmental circles to confront the consequences of the Armenian genocide was made abundantly clear. The postwar government proved reluctant to put on trial the Young Turk officials suspected of organizing the massacres. Only upon the insistence of the Allies were a series of trials initiated. Some dramatic evidence was given in testimony, and verdicts were handed down explicitly charging those found guilty of pursuing a course of action resulting in the destruction of the Armenian population. Even so, popular sentiment in Turkish society did not support the punishment of the guilty, and the government chose to forgo the sentences of the court. The triumvirs —Enver, Talaat, and Jemal — were condemned to death, but their trials were held in absentia since they had fled the country and their extradition was not a matter of priority (Dadrian, 1989, pp. 221–334).

Under these circumstances, no legal recourse to justice remained open. A clandestine Armenian group called Nemesis decided to mete out punishment to the accused individuals. The principal figures in the Young Turk Party, such as Talaat and Jemal, who conceived and implemented the genocide, were assassinated. All of them had fled Turkey, since their enemies included more than just Armenians. They also had much to account to the Turkish people for having taken them into a war which they lost so disastrously. Although the acts of retribution against Talaat and some of the others had a profound emotional effect on the Armenians, politically they were insignificant. The Armenians were never compensated for their losses (Derogy, 1990; Power, 2002, pp. 1–16).

Is There Agreement or Disagreement Among Legitimate Scholars as to the Interpretation of this Particular Genocide (e.g., Preconditions, Implementation, and Ramifications)?

Two schools of thought have emerged over the years. Scholars who study the Armenian genocide look at the phenomenon as either an exceptionally catastrophic occurrence coincident to a global conflict such as World War I (Fein, 1979, pp. 10–18; Horowitz, 1982, pp. 46–51), or the final chapter in the peculiar fate of the Armenians as a people who lost their independence many centuries earlier (Kuper, 1981, pp. 101–19; Walker, 1980, pp. 169, 236–37).

All agree that the preconditions to the genocide were highly consistent with other examples where a dominant group targets a minority. They also agree on the structural inequalities of Ottoman society and how it disadvantaged the Armenians. They differ on their interpretation of the causes and consequences of Armenian nationalism. Some think that the appearance of political organization among the Armenians can be regarded as the critical breaking point. Others see these developments as inevitable and entirely consistent with global trends and not particular to the Armenians. Two questions are often debated: whether the massacres during the reign of Abdul-Hamid were sufficiently precedental to be regarded as the beginning of the Armenian catastrophe, or whether the Young Turks aggravated conditions in ways that exceeded the designs of Abdul-Hamid (Kuper, 1981, pp. 101–19; Horowitz, 1982, pp. 46–51).

In the implementation of the genocide, one thing is clear. The earlier massacres were episodic and affected select communities. The genocide was systematic, comprehensive, and directed practically against everyone. The sultan’s policy did not aim for the extermination of the Armenians; rather, it was brutal punishment for aspiring to gain charge of their political destiny. As many scholars have pointed out, at one time the Ottoman system extended a considerable measure of security to its minorities. Although for the most part they were excluded from govern- ment and at a disadvantage in holding large-scale property, Christians and Jews were allowed to practice their faiths and distinguish themselves in commerce and finance. Therefore, it was not in the interest of the sultan to dismantle his imperial inheritance. His objective remained the continu- ance of his autocratic power and his rule over the lands bequeathed him by his conquering forebears.

Those studying the Young Turks have pointed out that the CUP organized its committees and conducted its activities outside this system. They were opponents of imperial autocracy. Their own political radicalism also meant that they were predisposed to think in exclusionary terms. Some of these scholars contend that the Young Turk period can be seen as a transitional phase in Turkish society where the pluralistic construct of the multiethnic and multiconfessional Ottoman system was violently smashed and the ground was prepared for the emergence of a state based on ethnic singularism (Ahmad, 1982, pp. 418–25; Staub, 1989, pp. 173–87; Melson, 1986, pp. 61–84).

Perhaps the issue debated most frequently revolves around the matter of postgenocide responsibility. There is a wide divergence of opinion on the question whether modern Turkey is liable to the Armenians for their losses, or whether it is absolved of such liability because the crime was committed under the jurisdiction of prior state authorities (Libaridian, 1985, pp. 211–27). The Turkish government dismisses all such claims since

it denies that the policies implemented in 1915 constitute genocide. Some in the academic and legal community are supportive of the Turkish position (Gürün, 1985). On the other hand, that stance raises a more complex problem. Who exactly should be held responsible for genocide: the government, the state, society? If governments put the blame on prior regimes, all they have done is merely certify the former policy by disregarding the consequences of genocide. The reluctance by a successor state to shoulder responsibility is only another form of reaping the benefits of mass murder.

Do People Care about this Genocide Today? If So, How Is that Concern Manifested? If Not, Why Not?

For a period of about 50 years, the world fell into an apathetic silence over the Armenian genocide. Its results had been so grievous for the Armenians and the failure of the international community to redress the consequent problems was so thoroughgoing that the world chose to ignore the legacy of the Armenian genocide. With the consolidation of Communist rule in Rus- sia and of Nationalist rule in Turkey, the chapter on the Armenians was considered closed. People wanted to forget about the Great War and its misery. As for the Armenians, they were too few, too widely dispersed, and too preoccupied with their own survival to know how to respond.

The concern over the fate of the Armenians manifested mostly in literature, as various authors wrote about the massacres and memorialized the rare instances of resistance (Lepsius, 1987; Gibbons, 1916; Werfel, 1934). After a life of struggle, upon reaching retirement age, Armenians also began to write down their memoirs. Slowly a small corpus of literature emerged, documenting in personal accounts the genocide and its con- sequences for individuals, their families, and communities (Hovannisian, 1987; Totten, 1991). This body of work began to serve as evidence for the study of the Armenian genocide. In the 1960s, as government archives holding vast collections of diplomatic correspondence on the deportations and massacres were opened, a significant amount of contemporaneous documentation also became available (Hovannisian, 1987; Beylerian, 1983; Ohandjanian, 1988; Adalian, 1991–1993; Dadrian, 1994). This further encouraged research in the subject. Interest in the Armenian genocide has since been growing as more researchers, writers, and educators examine the evidence and attempt to understand what happened in 1915 (Adalian, 1999b).

Commensurate to this interest, however, has been a phenomenon growing at an even faster pace. This is the denial of the Armenian genocide. For many Turks the reminder of the Ottoman past is offensive. The Turkish government’s stated policy has been a complete denial

(Foreign Policy Institute, 1982). The denial ranges beyond the question of political responsibility. This type of denial questions the very historical fact of the occurrence of genocide, and even of atrocities. A whole body of revisionist historiography has been generated to explain, to excuse, or to dismiss the Armenian genocide (Hovannisian, 1986a, pp. 111–33; Dobkin, 1986, pp. 97–109; Adalian, 1992, pp. 85–105).

Some authors have gone so far as to place the blame for the genocide on the Armenians themselves, describing the deportations and massacres as self-inflicted, since, they say, the deportations were only counter-measures taken by the Ottoman government against a disobedient and disloyal population (Uras, 1988, pp. 855–86; Gürün, 1985). Such arguments do not convince serious scholars (Guroian, 1986, pp. 135–52; Smith, 1989, pp. 1–38). Others, regrettably, are more prone to listening to revisionist argumentation (Shaw and Shaw, 1977, pp. 314–17; McCarthy, 1983, pp. 47–81, 117–30). These kinds of debates fail to address, however, the central questions about the Young Turk policy toward the Armenian population. Was every Armenian, young and old, man and woman, disloyal? How does one explain the deportation of Armenians from places that were nowhere near the war zones, if removing them from high-risk areas was the purpose of the policy? And always, one must ask about the treatment of children. What chance did they stand of surviving deportation, starvation, and dehydration in the desert?

What Does this Genocide Teach Us if We Wish to Protect Others from Such Horrors?

Although, ultimately, it is the exercise of political power in the absence of moral restraint that explains the occurrence of genocide, the demographic status of a people is demonstrated by the Armenian genocide to be a significant factor in the perpetration of genocide. A dispersed people jurid- ically designated by a state as a minority, both in the numerical and politi- cal sense of the word, is extremely vulnerable to abusive policy. It lacks the capacity for any coordinated action to respond to, or resist, genocidal mea- sures. It is evident that a government inclined to engage in the extermina- tion of a minority can only be restrained by pressures and sanctions imposed by greater powers.

Geography was no less a contributing factor in exposing the Armenians to genocide. A people inhabiting a remote part of the world is all the more at the mercy of a brutal government, especially if it is questioning the policies of the state. Since exposure is the principal foil of crime, the more hidden from view a people lives, the more likely it is to be repressed. Of all the places where the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire might have hampered the war effort, if indeed they were a seditious population, the

most likely spot would have been the capital city. Yet the government spared most of the Armenians in Constantinople because many foreigners lived there, and they would have been alarmed to witness mass deportations. That signal exception underscores the importance and the high likelihood of successfully monitoring the living conditions of an endangered population.

That exception also points to another lesson, which is specially pronounced in the Armenian case. Since many foreign communities had a presence in Constantinople, getting the word out to the rest of the world would not have been difficult with such corroboration. Thereby the Armenians in this one city remained in a protected enclave. This principle applies no less to the international status extended an entire people, as the European powers once did for the Armenians. Their interest in the Armenians acted as a partial restraint on the Ottoman government. The sudden alteration of the international order as a result of global conflict left the Armenians wholly exposed. Whatever the level of international protection extended to an endangered minority, the withdrawal of those guarantees, tenuous as they might be, only acts as an inducement for genocide. Denying opportunity to a criminal regime is critical for the prevention of genocide.

The experience of the Armenian people in the period after the genocide teaches another important lesson. Unless the consequences of genocide are addressed in the immediate aftermath of the event, the element of time very soon puts survivors at a serious disadvantage. Without the attention of the international community, without the intervention of major states seeking to stabilize the affected region, without the swift apprehension of the guilty, and without the full exposure of the evidence, the victims stand no chance of recovering from their losses. In the absence of a response and of universal condemnation, a genocide becomes “legitimized.” Following the war, the Ottoman government never gave a full accounting of what happened to the Armenians, and the successor state of Turkey chose to bury the matter entirely (Adalian, 1991, pp. 99–104).

Though all too frequently unwilling to take concerted action to save populations clearly in danger of annihilation, whether through monitoring and reporting systems, the activation of legal and economic sanctions, or political or military intervention, the international community is far better equipped to respond to genocidal crises than ever before. When the Armenian genocide occurred there was no alarm and there was no rescue. Without alarm there can be no rescue, and that is the least that the Armenian experience teaches.

Eyewitness Accounts: The Armenian Genocide

Eyewitness and survivor accounts of the Armenian genocide were audiotaped and videotaped more than a half century after the events. That means the recorded testimony was provided by persons in their 70s and 80s who were reflecting upon a life that took a sudden turn when they were still children or very young adults. Hence, the problem of the great length of time that passed since the events of 1915 and the fact that those events were seen through the eyes of children who were looking at the world from their very narrow frames of reference needs to be kept in mind when dealing with testimony of this type. Certainly children have the greatest difficulty gauging an accurate measure of time. Therefore, the episodes from their personal narratives occur at approximated intervals. Their memory, for instance, preserves the first names of numerous acquaintances, but last names are less frequently known.

A contrast to these limitations is the accuracy, with virtually all survivors, in their depiction of the geography and the topography that was the setting of their life’s most tragic period. Because they were deported, knowledge of where they originated and the places they saw and stopped along the way and the spots they reached at the end of their journeys became vital information not only for their physical and emotional survival, but also for their ability to reconnect with other survivors of the communities from which they were separated. Most interesting, however, and useful for the documentary record it turns out, was their very limited sense of the world around them. Whereas adults would have attempted to understand the events they witnessed in terms of their community and society, children describe their experiences strictly from within the confines of their immediate family and circle of friends. As such, therefore, they preserve a sense of greater pathos undiluted by either fatalism or drama. Most seem to have retained their horror of genocide through their inability to offer any larger suggestion than their very incomprehension at what happened and why.

Helen Tatarian’s account is an exceptionally rare one because it describes a massacre of Armenians that happened in 1909. When these records were created, very few survivors were old enough to have lived through occurrences of massacres earlier than 1915. The details of her account are also a valuable contrast to the pattern of the 1915 genocide. The Adana massacre is characterized by random mob action occurring within the perimeter of the city. Government forces are described as a party that simply stayed out of the way and, in this case, provided safe conduct where foreigners, specifically Americans, were concerned. More importantly, she verifies the significance of the protection provided by the missionary, and other third-party, presence. During the genocide none of these factors came into play. The missionaries were unable to protect their

parishioners. The government was an active participant in the dislocation and the execution of the Armenian population. Lastly, with the exception of some towns in the farthest eastern reaches of Anatolia, little killing occurred within the towns. The other survivors all testify to a consistent pattern of separation, deportation, and subsequent mass executions in places away from urban centers during the period of the genocide.

Sarkis Agojian records the treatment of the adult male population that was never deported. He testifies that they were arrested, tortured, and murdered very early in the process. The deportations, as he recalls, occurred after the segment of the Armenian population capable of resistance was eliminated. Lastly, his memory preserves, with a powerful poignancy, the trauma of Armenian children who were spared deportation and starvation by adoption into Turkish families. The deafening silence at his last glimpse of his mother and the shattering news of her death capture the maddening grief that seized their young lives, and which marked them for all their years.

Takouhi Levonian gives an eyewitness account of an actual episode of wholesale slaughter. Her description of the physical cruelties inflicted upon the Armenian population is especially riveting. Her description of the kinds of privations endured is no less powerful. Her testimony incontrovertibly underscores the extreme vulnerability of the Armenian young female population. It would appear that the treatment they received was most abusive. The horrific sadism practiced by the perpetrators of the Armenian genocide is hereto testified in this single account.

Yevnig Adrouni’s story redeems humanity through a personal narrative of survival and rescue. Too young to be mistreated sexually, her exploits are testament to the spirit of an alert child who would not submit to degradation. Spared physical torment, she committed herself to escaping her fate. Clutching onto the last shreds of her Armenian identity, she proves to herself and her rescuers that determination and defiance can, sometimes, defeat evil. As she so vividly recounts, from the survival of a single human being springs forth the new hope of larger victories.

Helen Tatarian, native of Dertyol, born c. 1893. Audiotaped on April 17, 1977, Los Angeles, California by Rouben Adalian. (Dertyol was a town inhabited mostly by Armenians. It is located on the Mediterranean coast in the region of Adana. Adana is also the name of the largest town in the area.)

There was a massacre in 1909. I was in school at Adana. Miss Webb and Miss Mary, two American sisters, ran the school. Miss Webb was the older, Miss Mary the younger.

In 1909, right in the month of April, we suddenly heard guns being fired and saw flames rising. The houses of the Armenians were set on fire.

There was a French school right next to ours. They burned it down completely.

At first the Turks killed quite a lot of people, then they stopped for a while. Eight days later they started firing their guns again. Reverend Sisak Manoogian came running. “Do not be afraid children, a hog had gone wild,” he said, “and they are shooting it.” But it was a lie, nor had a hog gone wild. The Turks had gone wild. They were about to start again.

The son-in-law of our American missionary, Mr. Chambers, had climbed on the roof. He had climbed on the roof of our laundry room to look at what was going on in the city. They shot the man.

There was a window, a small window up high. We used to look from there to see that behind the school building there were people lying dead. The Turks were shooting the Armenians. This was a massacre specifically aimed at the Armenians.

During the fire those who managed to hide remained in hiding, those who did not hide were cut down. Just like Surpik grandmother, the poor woman who was going to her brother-in-law’s house. Surpik grandmother was shot in the arm, great grandmother Surpik. Later they had shot dead her husband and son. This woman owned fields. She was a rich woman. She used to travel on horseback. But it so happened that she was going in the direction of her relatives, her brother-in-law’s house. Fortunately she was not killed.

We could not go out and we remained in hiding in the school building. We heard the sounds of guns, and from the sounds alone we were afraid. We were children. We cried, but we had no communication with anyone outside. Across from our building there lived an American, Miss Farris. The Turks burned her building so that our school would catch on fire and the children would have to run outside and thus they could kidnap the girls. The American missionary immediately notified the government. Soldiers came from the government and while putting out the fire a soldier fell and was burned inside.

Later we opened a hole in the wall. The missionaries did this. They opened a hole big enough to go through it in order to cross from our end of the block to the other end, to Mr. Chambers’ house, the missionary’s house. All the girls were there, 250, 300 girls. We piled up in the man’s house. The Turks were going to burn this house also. The man held out a surrender flag. They had poured gas and threatened to burn us in that house. We asked him: “Reverend, if the Turks forced you, would you hand us over to them?” “If they press me hard. If they insist,” said the man. What could he do? Or else they would kill him too. Later we remained there for a night. There, we cried. The girls began such a weeping. The following morning, the government soldiers took us to the train station. By train we went to Mersin.

There was no fighting [in Adana between Armenians and Turks]. The Turks knew anyway which was the house of an Armenian. They went in and cut him down and shot the people inside and they took whatever was in the house. They robbed the houses and set them on fire. They entered them since it was the property of the Armenians. They also burned the churches, but I believe a considerable crowd had gathered in a French church. They did nothing there at that time. There were those who took refuge with our American missionaries also, but it was a little difficult to cross the street. If the Turks saw you, they were ready to shoot.

Sarkis Agojian, native of Chemeshgadsak, born 1906. Audiotaped on May 25, 1983, in Pasadena, California, by Donald and Lorna Miller (Chemeshgadsak was a town inhabited by Armenians in the region of Kharpert in the western portion of historic Armenia.)

We were in school having physical education. We had lined up when the wife of our coach, Mr. Boghos, came and told her husband that the Turks had just arrested the principal, Pastor Arshag. You see, they first took the educated, the intellectuals. They took these people to a home which they had converted into a prison and tortured them in order to get them to talk. The mailman, who was Armenian, was also arrested and tortured. They pulled out his fingernails saying that while he was carrying mail he also was transporting secret letters; mail was carried in those days on horseback in large leather bags fastened to either side of the horse. He was Sarkis Mendishian. So upon the news that Pastor Arshag was arrested, they dismissed us from school and asked all of us to go home.

We went home. My father was not there. My uncle had run away. They had put a dress on my uncle’s son, even though he was not young, to disguise him. My father’s uncle was also in prison, for, after taking the younger educated men, they also took the elderly. I was young so they used to send me to take food to him. I did this a few times. I would go in and sit with him. One day when I was taking his food, I met a lot of police who were saying that on that day we could not deliver food — that all the prisoners were going to leave. I saw them in twos, all chained together. I could not take the food, so I returned and gave the news. I told them that they were chained and they were coming this way and would pass by our house, there being no other way to leave town toward Kharpert.

By now, all the families had heard, so they were all in the streets to see their loved ones. I got on top of the roof and was yelling “uncle.” There was a doctor in this procession, and when his wife saw him, she ran out to greet him, but with the butt of the rifle the police pushed her away — even though he was an elderly man. So the men marched on, leaving all the women and families crying and grieving. There was a place outside of town about 20 minutes with trees and water. There they took their names to see if anyone was missing. Then they marched them to the edge of the Euphrates and killed them. Apparently my great uncle had some red gold with him; he gave it to the police who took it and then killed him.

Now that all the men were gone, deportation orders were issued for women and children. Our town was deported in two different groups, 15 days apart. I wish we were in the first group because they made it all the way to Aleppo. When we were to leave our home, we left our bedding and other things with the landlord so that if we returned we would get it back. Also, we threw our rugs to the people at the public bath next door so that they would keep them for us. We said that we would get them when we returned. We are still to return!

Because we could afford it, we had rented a cart to carry some of our things. It was five hours from our town to the Euphrates River. On the way we had to pass on a bridge. We were told that one of our neighbor’s boys had been killed and thrown over there. In fact, I heard some Turk boys saying to each other that there was a gold piece in the pocket of our neighbor’s son. We could see the injured who had been shot but were not yet dead.

The first village that we reached was one in which our landlord lived. We saw that the fruit was getting ripe. My brother, sister, uncle’s son and daughter took some money to our landlord to see if he would save their lives, and they remained with him. I stayed with my mother, my uncle’s wife, and her five-year-old grandchild. We left the village of Bederatil and went to the next town, Leloushaghen, which took us a day to reach. There was a Turk man who was taking Armenian boys away, and I said that I would go with him.

That night, I and two other boys slept at this Turkish agha’s house. In the morning my mother brought a bundle of clothes for me and left it with a Turkish woman whose husband had worked in my father’s bakery and who had lived with this agha for years. I was there when she came to the house to leave my clothes. I was sitting there and I saw her, but it was as though I was in a trance; we never talked and she never kissed me. I don’t know if it was because she could not bear it from sadness. I never saw again any of those clothes or anything that my mother might have left in them for me.

The deportation caravan now went on without me; they still had two hours to make it to the Euphrates River. When they got there, they were all killed. The way we heard this was that some of the police brought to the agha a pretty young girl and her brother that this Turk wanted. These police told the agha that in a matter of a few minutes they wiped them all out. But this young Armenian girl told us that she saw the gendarmes force the deportees to take off their clothes and then shove them off a cliff into the Euphrates River far below. According to this girl, when it came time for