The secret on the ocean floorA wave of pioneers is poised to scoop up treasure from the deep sea.

But was this ocean mining boom sparked by a 1970s CIA plot?19 February 2018

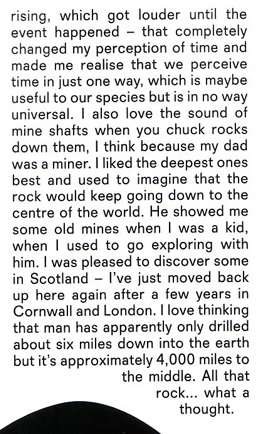

Mystery shipIn the summer of 1974, a large and highly unusual ship set sail from Long Beach in California.

It was heading for the middle of the Pacific where its owners boasted it would herald a revolutionary new industry beneath the waves.

Equipped with a towering rig and the latest in drilling gear, the vessel was designed to reach down through the deep, dark waters to a source of incredible wealth lying on the ocean floor.

It was billed as the boldest step so far in a long-held dream of opening a new frontier in mining, one that would see valuable metals extracted from the rocks of the seabed.

But amid all the excited public relations, there was one small hitch - the whole expedition was a lie.

This was a Cold War deception on a staggering scale, but one which also left a legacy that has profound implications nearly half a century later.

The real target of the crew on board this giant ship was a lost Soviet submarine. Six years earlier, the K-129 had sunk 1,500 miles north-west of Hawaii while carrying ballistic nuclear missiles.

The Russians failed to find their sub despite a massive search, but an American network of underwater listening posts had detected the noise of an explosion that eventually led US teams to the wreck.

It was lying three miles down, deeper than any previous salvage operation. The weapons and top-secret code books were surely beyond reach.

But in the struggle for military advantage, the sub represented the crown jewels – a chance to explore Moscow’s nuclear missiles and to break into its naval communications.

So the CIA hatched an audacious plan, Project Azorian, to retrieve the submarine. That would have been hard enough. But there was another challenge as well - it had to be done without the Russians knowing.

The spies needed to create a smokescreen so they pretended to be exploring the possibility of deep sea mining.

A PR campaign conveyed a determined effort to find manganese nodules. These potato-sized rocks lie scattered in the abyss, the great plains of the deep ocean.

There had to be a frontman - someone rich and eccentric enough to be plausible. The reclusive billionaire inventor Howard Hughes was perfect for the role.

He agreed to take part and, in his name, a unique ship was designed. Publicly, it was fitted with everything needed to dig up the seabed.

But, covertly, the Hughes Glomar Explorer was also built with ingenious devices straight from a Bond film. The ship’s hull had enormous doors that could swing apart to create a “moon pool”, an underwater opening large enough to accommodate the Soviet sub and keep it hidden.

Tucked away out of sight inside the ship was a “capture vehicle” which had a giant set of claws to straddle the sub and secure it.

It took until 1974, six years after the sinking of the sub, for the CIA to be ready. The cost of the project - $500m - was equivalent then to building a couple of aircraft carriers or launching an Apollo mission to the moon.

"We really misled a lot of people and it’s surprising that the story held together for so long”

-Dave Sharp, former CIA operative

No-one had ever attempted anything on this scale in such incredible depths. The sub itself had a weight of nearly 2,000 tonnes but the three miles of thick steel pipe needed to haul it up added even more.

New systems were needed to keep the Glomar Explorer in position as well as to handle the huge load, and everyone on board was nervous. Dave Sharp, one of the few CIA figures happy to talk about the project, tells me it was “really frightening” when heavy seas threatened to tear their unusual vessel apart.

Dave Sharp, pictured aboard the Hughes Glomar Explorer

Dave Sharp, pictured aboard the Hughes Glomar Explorer But even more alarming was the suspicion of the Russians. To convince them that Howard Hughes was genuinely interested in nodules, executives were despatched to conferences on ocean mining where they described in detail their plans to harvest the rocks.

“We made ocean mining seem a lot more credible,” Sharp says. “We really misled a lot of people and it’s surprising that the story held together for so long.”

The cover was so good that it prompted US universities to move to start courses in deep sea mining and it also whipped up the share prices of the companies involved. “People thought, ‘if Howard Hughes is into it, we need to be too’,” says Sharp.

“We even collected a few nodules,” he remembers, which was fortunate because Soviet spy ships kept a constant vigil and once even came close enough to overhear the Americans’ conversations.

“When we realised they were right alongside, we started talking about nodules, like ‘here’s a good one’ so it looked like we were checking them.”

Yet another complication arose. The project needed calm weather and that was only likely in summer. But just when it was about to begin in summer 1974, US President Richard Nixon was visiting Moscow for a peace-making summit.

Being caught stealing a Soviet sub would not exactly have helped, so Nixon insisted that the operation could not begin until he had left Russia. That was on 3 July. By then the Hughes Glomar Explorer was in position and the winches whirred into action the next day.

Things did not go smoothly. Sharp recalls that pumps and connections kept breaking. Huge vibrations rocked the ship as the “capture vehicle” was “banging back and forth in the waves”. But on 30 July, he watched as underwater cameras relayed video of the sub as well as “dozens of crawling crab-like crustaceans” and a big white fish that looked like a shark.

Inside the Hughes Glomar Explorer control room

Inside the Hughes Glomar Explorer control roomAmazingly, the giant steel claws successfully seized the sub. But then disaster struck. At some point on the way up, the immense strain became too much, part of a claw snapped off and most of the sub slipped back to the seabed.

Only the front section made it up. The bodies of six Soviet submariners were recovered and were later given a formal burial at sea. But the missiles and code books were never found.

The CIA official history asserts that the operation was one of the greatest intelligence coups of the Cold War, but it had cost vast sums and questions immediately arose about its value. A year later, the sensational details became public and plans to recover the remaining section were abandoned.

As Sharp puts it, the revelation that the deep sea mining project was fake was “a sudden shock” to other mining companies and also to diplomats at the UN who were right in the middle of negotiating future rights to ocean minerals. Share prices tumbled amid a wave of recriminations.

This might have derailed the very notion of deep sea mining for good. But in fact it proved that with clever engineering and a lavish budget it was possible – just - to operate in the otherworldly depths. “It’s really difficult but we showed it could be done,” says Sharp.

The man who digsIn an air-conditioned cabin in a teeming port in Papua New Guinea, Leslie Kewa reaches for a joystick that will control a machine the size of a house. Nearly half a century after the CIA men pretended to mine the ocean floor, he’s about to do it for real.

A burly figure with a kindly face, Kewa is from a village in the remote highlands of Papua New Guinea. In a country blighted by poverty, he grew up in relative comfort because his father, and the rest of the men in his family, made careers in the mining industry. Kewa became a specialist in handling gargantuan devices.

But the one standing nearby is unique, not only because of the destructive power of its whirling steel teeth, and its menacing resemblance to something from a Mad Max film, but also because it’s designed to be used far beyond human reach.

As Kewa’s fingertips send the first commands, and the machine crunches over the ground outside, he admits to feeling a bit scared.

In these first trials, he’s learning to steer by remote control, relying on CCTV to show him where the huge steel tracks are pointing as they inch their way forward. “I’m used to the feel of machinery in my hands so having to trust the equipment and the screens is hard,” he says.

But there’s no other option. The machine will soon be deployed not in the huge pits of an opencast mine on land but in the sunless depths a mile underwater on the ocean floor.

If work starts as planned next year, Kewa will earn himself a place in history as the first person to break rock in the world’s first deep sea mine.

Run by a Canadian firm, Nautilus Minerals, the project will be managed from a ship in the tropical waters of the Bismarck Sea off Papua New Guinea. Three of the vast machines will be lowered to the slopes of an undersea volcano.

There they will encounter a stretch of seabed covered in hydrothermal vents. These strange twisting chimneys are formed by boiling water blasting up from the rock.

As with most fields of vents, this one is astonishingly rich in valuable metals. The site is named Solwara 1 - “salt water” in the local language.

But the hydrothermal vents host thriving communities of marine life - snails, worms and shrimp that have evolved to cope with very specific conditions.

In some cases these creatures are extremely rare, which is why the prospect of deep sea mining is highly controversial.

The plan is for Kewa to guide the steel teeth of the mining machines so they methodically demolish the vents, pulverising them into fragments.

The tiny pieces of rock should then be small enough to be piped up to the surface. On board the ship, a processing plant will churn out a multitude of specks of copper and gold that could be worth billions. A Chinese firm has already agreed to buy the lot.

Once the riches of Solwara 1 have been extracted, the machines will be moved to another dozen sites lined up nearby.

On the sea bed the ores are exceptionally rich. Every tonne of material dug up in a typical copper or gold mine on land only yields a tiny fraction of useful metal.

By contrast, the hydrothermal vents off Papua New Guinea are at least 10 times richer.

And it’s the same story with gold and many other metals too. A Japanese expedition to another set of vents off Okinawa discovered enough zinc to keep Japan supplied for an entire year. Those behind that project kept it quiet until it was over, causing real surprise in the mining industry.

Nautilus Minerals forecasts that in copper alone an emerging undersea industry in oceans around the world could be worth $30bn a year by 2030. And it claims that by mining a small area of seabed, the venture will be friendlier to the environment. It contrasts its work with mines on land where trees and topsoil are swept away across vast areas.

The footprint of the Solwara-1 mining area, compared with an existing copper mine in South Australia

The footprint of the Solwara-1 mining area, compared with an existing copper mine in South AustraliaFor the government of Papua New Guinea, the attraction is obvious - badly needed income as a partner in the venture. And Nautilus has agreed to funnel some of the proceeds to local administrations too, to let ordinary people benefit.

But the history of mining in Papua New Guinea does not inspire confidence. Millions still live well below the poverty line despite the massive extraction of ores from the mountains.

And for some, venturing into the sea spells danger for precious waters.

Threatened waters Jonathan Mesulam first heard about deep sea mining when he was reading the business section of a newspaper. The story shocked him. Born and brought up in Papua New Guinea’s New Ireland, he realised that the site of Solwara 1 was only about 15 miles (25km) from his home on the shore.

“As soon as I read the article I felt so numb,” Mesulam says.

Like many parts of Papua New Guinea, his village has the appearance of a tropical paradise. Palm trees overlook aquamarine shallows and wooden fishing boats lie on the golden beaches.

But the beauty masks a chronic lack of development. People live in homes built of bamboo and sago leaves. Mesulam himself achieved a big break by becoming a secondary school teacher, but he has shunned city life to be at home to fight the mine.

“We have a connection with the sea,” he says. “It’s been part of our culture for generations and traditional knowledge of the sea goes back to our ancestors.”

Polite and softly spoken, Mesulam says the coastal communities depend on fishing which could be threatened if the waters are filled with dust generated by the mining, or if they are polluted.

The tuna industry employs thousands in Papua New Guinea. And the villages on New Ireland are famous for the unique practice of “shark calling” - local people lure the creatures to their boats and soothe them before hauling them in.

All this, Mesulam says, could be “grievously harmed” by digging up the ocean floor, and he’s become a leading figure in a campaign group, the Alliance of Solwara Warriors, which is opposing Nautilus Minerals.

The company says that at a mile deep, the mining will be far below the habitats of any important fisheries and will not affect them.

“Where we’ll be operating, it’s cold and dark,” says one senior Nautilus executive. “There are no tuna there, they need entirely different conditions near the surface of the ocean.”

This reassurance has been emphasised in public meetings. And Nautilus has also been investing in community relations, paying for mobile health care and even a new bridge.

For Mesulam this is mere PR. He calls the mine “experimental” - there could be unexpected consequences, and he has the churches and some politicians on his side.

But he’s up against a great force - the incredible and surging demand the world has for key minerals.

Our need Stung by accusations that they are failing to tackle dirty air, governments around the world are setting new standards for cleaner vehicles. That means millions more electric cars in the next few years.

All the batteries and the wiring, the processors and the charging points, will need raw materials. Last year the German giant Volkswagen tried to corner the market in cobalt. Supplies of lithium are also in hot demand. And copper has never been so badly needed.

And with renewable power like wind and solar being installed at a frantic pace, every turbine and every panel also requires key metals. Add to that the boom in consumer electronics and there are real concerns about future supplies.

With cobalt, it’s estimated that by 2025 Volkswagen will need one-third of the current entire global supply for its electric cars.

Massive new battery factories are being constructed – like Tesla owner Elon Musk’s famous Gigafactory - and they too will be hungry for cobalt.

Bram Murton, a geologist with the UK’s National Oceanography Centre, says that if all the cars on Europe’s roads are electric by 2040, and if they use the same kind of batteries as the Tesla Model 3, that would require 28 times more cobalt than is produced right now.

At the moment more than 60% of all cobalt comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo. For decades allegations of corruption and human rights abuses have swirled around parts of its mining industry.

Last year Amnesty International said there were children as young as seven working in the DRC’s cobalt mines, “in narrow man-made tunnels, at risk of fatal accidents and serious lung disease”. Microsoft, Renault and Huawei were among the companies named as failing to check if their supplies of cobalt involved child labour. They’ve all since promised to improve their systems for checking how cobalt is sourced.

Advocates of exploiting the ocean also point to the size of mines on land compared with those that would be operated underwater. Kennecott in Utah and Chuquicamata and Escondida in Chile involve mind-bogglingly large holes in the ground. They stretch nearly three miles across (4km) and reach more than half a mile deep (645m-1200m).

By contrast, the Solwara 1 mine, in the waters off Papua New Guinea, will be small – 1150ft (350m) across and 65ft (20m) deep.

For Michael Lodge, secretary general of the International Seabed Authority, a UN body set up to manage deep sea mining, there’s a clear case for pressing ahead.

“Are we going to continue to develop huge mines that destroy villages, alter rivers, pollute water courses, take thousands of years to restore, remove whole mountains? You don’t have any of that with deep seabed mining.”

Looking for nodules The first inkling that the ocean floor might hold a treasure trove of minerals came in the late 19th Century when a Royal Navy ship, HMS Challenger, was sent on a pioneering expedition. Instead of exploring the coasts of new lands, the ship was to investigate the oceans themselves.

The ship’s scientists discovered the existence of underwater mountains in the Atlantic, as well as establishing the presence of life in the deep. But perhaps their most unexpected find came from the seabed.

When the seabed was dredged, the nets brought up teeth from sharks and ear bones from whales but also small rocks. Initially described as “nodular concretions”, and looking a bit like cobblestones, it turned out that vast fields of them were lying on the sand and sediment.

In 1877, in a lecture given in Manchester, one of the expedition’s scientists, John Murray, reported that they were made up of manganese, iron and nickel.

Later expeditions confirmed that these manganese nodules were scattered across the seabed as far apart as the Pacific and Indian Oceans. By the 1950s, with the world’s population booming, researchers turned their attention to these potential resources.

In a book published in 1964, American marine geologist John Mero wrote that the nodules were so plentiful and so rich that even if only 10% of them could be mined, they would keep a world of 20 billion people supplied with key metals for “thousands of years”.

At that time the nodules were inaccessible and the prices for the metals weren’t nearly high enough to justify the effort.

But Mero had planted a germ of an idea.

On 1 November 1967, a UN committee was meeting in New York and the ambassador from the island nation of Malta was invited to speak. Dr Arvid Pardo faced an uphill struggle. He was suggesting that the deep oceans should be reserved for peaceful activities and that the mineral wealth should be shared by all of mankind.

Manganese nodules on the bed of the Pacific Ocean

Manganese nodules on the bed of the Pacific OceanSome delegations were already hostile, but Pardo was well prepared and passionate, even lyrical. The dark oceans, he said, “were the womb of life”. He then quoted John Mero’s research into the “astounding” contents of the billions of nodules lying untouched on the seabed – enough aluminium to last 20,000 years, zirconium for 100,000 years and cobalt for 200,000 years.

Pardo floated a radical suggestion - a slice of any earnings from deep sea mining would have to go to developing nations. This controversial concept was to be haggled over for decades.

But today, Pardo’s vision is becoming reality as the UN’s International Seabed Authority has drawn up maps dividing the ocean into blocks.

There are 29 exploration areas, licensed for mineral prospecting for 15 years. In total they stretch over an astonishing 500,000 square miles (1.3m sq km) of seabed in the Pacific, the Atlantic and the Indian Ocean. Ventures from 19 different countries have paid for the rights to investigate them.

China has four of them. Russia and South Korea each have three. France and Germany have two. And so does the UK, via a company called UK Seabed Resources. The company’s owner, Lockheed Martin, has an interesting connection. It was one of the contractors secretly hired by the CIA to retrieve the Soviet submarine – and it has remained genuinely interested in manganese nodules ever since.

Although no-one has yet started mining the ocean floor, dozens of research expeditions are under way “at an intense pace”, says Michael Lodge, from the International Seabed Authority.

Based in Jamaica, the ISA must come up with a set of rules before exploitation of the seabed can start in international waters - what environmental controls there will be and how much money will go to poorer countries.

Companies digging for minerals close to shore – like those in Papua New Guinea or Japan – need not wait because individual governments can decide what to do in their own territorial waters.

Lost creaturesNo deep sea mine can start operating until the ecology of each zone has been assessed. And the rush to mine has generated something unexpected - a wealth of new information about life in some of the least explored parts of the world.

Among those are thousands of new species ranging from sponges to crustaceans.

Pedro Martinez, who works at the Senckenberg Research Institute in Germany, told a conference at London’s Natural History Museum how hundreds of creatures spotted in the depths are completely new to science. “We don’t even have names for these species...there are no books to identify them.”

“The abyssal plains,” he asserted, “may have the highest biodiversity in the oceans, maybe the highest biodiversity on the planet.”

There’s an emerging scientific consensus that the tracts of ocean floor in line to be mined – whether hydrothermal vents or fields of nodules - are thriving habitats with intricate ecosystems. And they are still largely unknown.

Adrian Glover, a marine biologist at the NHM, has an analogy. Imagine trying to survey a rainforest while hovering in a hot air balloon. Making the task harder is a thick fog. And all you can do is lower a bucket at a few random points to drag up the odd branch and lump of soil. “Think of all the things you’d miss,” he says. “That’s what it’s like investigating the deep ocean.”

Some prospecting expeditions have not released their findings about marine life, as they’re meant to. And few of the ventures have the funding for biologists to publish detailed results. While Glover is optimistic that mining will not be allowed “in areas where they don’t know what lives there”, he says, “we do need a reasonable understanding and we just haven’t got that yet”. Until the biology is understood, the danger is that species will be wiped out.

One example is a type of hairy crab known as the Hoff. It lives in the Longqi – or Dragon’s Breath - hydrothermal vents in the Indian Ocean, an area which China is licensed to explore for minerals. Although it’s similar to crabs elsewhere, this particular variant may be unique.

The scaly foot snail is another rare creature only known to live in two spots in the ocean, both of which are licensed for mining.

While these might not be the most iconic symbols of conservation, they may later prove to have a key ecological role or even a medical application. Some deep sea organisms are known to have high levels of substances that may be useful in combating Alzheimers.

So what impact will mining have on marine life? Huge excavators will rumble over the seabed. Either they will tear up hydrothermal vents or they will vacuum up nodules. It will be highly destructive.

Michael Lodge admits that but also argues that the areas affected will be tiny compared with the vastness of the oceans – “much less than half a per cent” – and that big areas have been earmarked as reserves to be left untouched.

But many biologists wince at the thought of what might happen. Habitats in the path of the machines will obviously be wiped out. And a group of leading marine scientists recently warned of the risks of “unavoidable and possibly irrevocable” losses to biodiversity.

Mining will raise plumes of sediment - like clouds of dust from a quarry. This could affect marine life far beyond the mining site.

To assess what might happen if nodules are mined, Annemiek Vink and her colleagues at Germany’s Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources ran computer models. They assume that the massive mining machines might be as wide as five bulldozers, side-by-side, advancing over the sea floor.

That would stir up as much as 1,000 tonnes of sediment an hour. Within 10 days, she estimates, a thin blanket of dust could settle up to 12km away, smothering everything that lives there. A study released at the NHM conference says the effects on the ecosystems would “last many decades”.

And with so much uncertainty about the risks to the marine environment, the European Parliament has called for a moratorium on mining until more research is done.

We’ve drilled the ocean floor for oil and gas, scarred it with trenches for communications cables, poisoned it with old radioactive waste and chemical weapons, and polluted its remotest corners with a blizzard of discarded plastic. So, is mining a step too far?

I put that question to Sir David Attenborough at the launch of his series Blue Planet II. When he sees our video of the giant machines being readied in Papua New Guinea, he is aghast. “It’s heartbreaking,” he says.

His greatest concern is for the hydrothermal vents, those delicate mineral-rich chimneys which act as oases for unusual creatures.

“That’s where life began, and that we should be destroying these things is so deeply tragic - that humanity should just plough on with no regard for the consequences, because they don’t know what they are.”

But there is a vigorous debate among scientists.

The geologist Bram Murton has warned of “an ill-informed knee-jerk reaction” to ocean mining which, he says, offers the potential to support a low-carbon future.

But Glover says that ultimately it’s about whether it’s right for humans to go into an area and destroy species we know nothing about.

All this raises an awkward set of questions. Where should we get our minerals from? Should phones and wind turbines and electric cars carry a label explaining the origins of their raw materials?

Tins of tuna state that they are “dolphin-friendly” so should products using cobalt say if the metal was mined on land or in the ocean? What would the best choice be anyway? Should the vents so special to Attenborough be spared and only nodule mining allowed?

Some argue that proper recycling of metals would negate the need for deep sea mining in the first place, but others think that that won’t produce a fraction of what’s needed.

Time is running out to come up with answers. More than 40 years since the CIA faked a deep sea mining operation, the first genuine ones may start work far sooner than most people realise.