Putin's brain?ANTON SHEKHOVTSOV

12 September 2014Age of viceDugin became involved in social activities in his late teens, when he joined the underground Yuzhinskiy literary circle, in which occultism, esotericism and fascist mysticism were the subjects of numerous discussions and a way to escape Soviet conformism. The works of French Traditionalist René Guénon (1886-1951) and Italian fascist thinker Julius Evola (1898-1974) exerted a particularly strong influence on the young Dugin and became a philosophical foundation of the doctrine that he developed many years later.

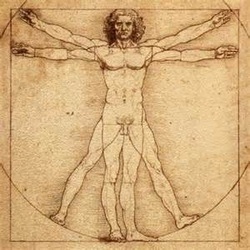

Aleksandr Dugin

Aleksandr DuginAt the core of Guénon’s Integral Traditionalism lies a belief in the “primordial tradition” that was introduced to humanity during the “golden age” and, as the world slid into decadence, gradually disappeared from people’s lives. This belief also implies that time is cyclic; hence, the “golden age” will necessarily succeed the current “age of vice”.

Evola politicized Guénon’s ideas of an unsurmountable opposition between the idealized past and decadent modernity even further. For Evola, this opposition was also the one between a closed and hierarchic model of society of the “golden age” and an open and democratic model of today’s “age of vice”. He also believed that a fascist revolution could end the present age of decay, and this would bring about a new “golden age” of order and hierarchy.

Young Dugin hated the Soviet reality and strongly associated it with the “age of vice”. Guénon’s and Evola’s works informed him of a delusive perspective of revolutionizing and re-enchanting history by ending the era of perceived degeneration and inaugurating the new era.

The projected renewal of the world required political activism, so in 1987, Dugin joined the National-Patriotic Front “Memory” (Pamyat), the most significant far-right organization at that time. In 1988, Dugin was elected a member of Pamyat’s Central Council but was expelled in early 1989, presumably for his attempts to change the ideology of the organization. In the early 1990s, Dugin began looking for contemporary western European followers of Guénon and Evola. His active participation in various conferences in western Europe introduced him to leading figures in the European New Right (ENR) – a network of European far-right intellectuals and journals.

The ENR has always been a metapolitical movement; rather than aiming to participate in the political process, it tried to pursue a strategy of modifying the postwar liberal democratic political culture. This strategy was adopted from the theory of cultural hegemony of Italian communist Antonio Gramsci (1891-1937). In its New Right manifestation, this “right-wing Gramscism” stresses the importance of establishing cultural hegemony by making the cultural sphere more susceptible to non-democratic politics through ideology-driven education and cultural production, in preparation for the far Right’s seizure of political power. Cultural hegemony is considered to have been established once the ideology of the political force seeking to establish it is perceived as common sense within society.

Despite the metapolitical nature of the ENR, its ideas have influenced many radical right parties in Europe. One particular idea of the ENR, namely ethnopluralism, is especially popular among the ideologues of the party-political far Right, as it champions ethno-cultural pluralism globally but is critical of cultural pluralism (multiculturalism) in any given society. ENR thinkers supplied Dugin with the most important ideological ammunition for creating Neo-Eurasianism.

Despite the name, Neo-Eurasianism has a limited relation to Eurasianism, the interwar Russian émigré movement that could be placed in the Slavophile tradition. Rather, Neo-Eurasianism is a mixture of the ideas of Guénon, Evola and the ENR, as well as the classical geopolitics and National Bolshevism to which Dugin was introduced in the beginning of the 1990s by Belgian New Right author Robert Steuckers. In Russia, for the sake of political and cultural legitimacy, Dugin argued for continuity between interwar Eurasianism and his own ideology, but his Neo-Eurasianism is firmly rooted in the western, rather than Russian, far-right intellectual tradition.

Dugin’s Neo-EurasianismDespite the metapolitical nature of the ENR in general and Neo-Eurasianism in particular, Aleksandr Dugin did try to become involved in the political process in the 1990s and early 2000s. The first attempt was associated with the marginal National-Bolshevik Party (NBP). In 1995, Dugin even contested elections to the State Duma, but he obtained less than one per cent of the vote. His second attempt to get involved in politics is associated with the creation of the Eurasia party in 2002, but already in 2003 the party’s other co-founder expelled Dugin from the party.

Since then, Dugin firmly settled on taking the metapolitical course. He founded the International Eurasian Movement in 2003 and was appointed professor at Moscow State University in 2008. From 2005 onwards, he also became a popular political commentator who frequently appeared on primetime talk shows and published in influential newspapers. This allowed him to bring his Neo-Eurasianist ideas directly to the academic world, whilst using his academic title as a prestigious cover-up for his irrational ideas.

Dugin became especially famous in Russia for the Neo-Eurasianist version of classical geopolitics. His book The Foundations of Geopolitics (published in 1997) outlined his political and ideological vision of Russia’s place in the world. According to Dugin, there is an irresolvable confrontation between the Atlanticist world (principally the United States and the United Kingdom) and Eurasia (predominantly Russia, Central and Eastern Europe and Asia) that resists US-led globalization and ethno-cultural universalization. This confrontation is also placed on the metaphysical plane: the alleged hegemony of Atlanticism and liberal democracy is interpreted as the triumph of the “age of vice”, while the Eurasian revolution that would establish the Russia-led Eurasian empire is understood as an advent of the “golden age”.

Subscribing to the idea of ethno-pluralism, Neo-Eurasianism suggests that “Russians shall live in their own national reality and there shall also be national realities for Tatars, Chechens, Armenians and the rest”. At the same time, the Russians are considered to be “the top-priority Eurasian ethnos, the most typical one”, and “they are most fit for carrying out a civilizational geopolitical historical mission” of creating the Eurasian empire. However, the Russian people are seen as being in decline, hence, the improvement of the Russians’ “severe condition in the ethnic, biological and spiritual sense” should be addressed by appealing to “the most radical forms of Russian nationalism”. It is necessary “to consolidate our ethnic, ethno-cultural identity – Orthodox and Russian”, “to introduce norms of ethno-cultural hygiene”.

Neo-Eurasianist foreign policy is revisionist, expansionist and implacably opposed to the United States. It draws considerably on the theories of convicted Belgian Nazi collaborator Jean-François Thiriart (1922-1992), who proposed the creation of the “Euro-Soviet empire from Vladivostok to Dublin” in the late 1970s. Dugin reinterpreted the Euro-Soviet empire as the essentially similar Eurasian empire which includes not only Russia, but the whole of Europe as well, so the Neo-Eurasianist agenda implies the “liberation” of Europe from all Atlanticist influences. In 1938, Thiriart praised the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact as he saw the Soviet-Nazi alliance to be a strong force against the US. For Dugin, too, the Berlin-Moscow axis is crucial in creating a Eurasian empire. Here, Moscow and Berlin are symbols of two geopolitical centres of power. Moscow is the centre of the Russia-dominated space that would include Russia, the countries of the northern Balkan Peninsula, Moldova, Ukraine (excluding western Ukraine), eastern Belarus, central Asia and Mongolia. Berlin is the centre of a Germany-dominated space called “Mitteleuropa” that would include Germany, Italy and most of the territories of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Ideology for saleDugin was a staunch opponent of Boris Yeltsin, but hailed the ascent of Vladimir Putin. In 2001, he wrote that Putin had completed six out of “Twelve Labours”: he prevented the failure of Russia in the Caucasus region; put local governors under control; introduced federal districts in Russia corresponding to the military districts; got rid of the oligarchs who controlled two of the main Russian TV channels; started the integration process in the post-Soviet space and announced the creation of the Eurasian Economic Union; and formalized the thesis concerning the need for a multipolar world. What Putin still needed to do was to fully complete the previous six “Labours”: to clarify his position towards the US; to recognize the dead-end nature of “radical liberalism” in the economy; to allow for a rotation of the elite; to form his own efficient team that would help him in reforming the country; and to assign the Eurasianist ideology as the fundamental worldview of the future Russia.

It seems plausible that Dugin wanted Putin to accept him as the ideologue of Russia and the projected Eurasian empire. In his speech at the inaugural congress of the Eurasia party, Dugin said that the party was going to rally around Putin and “delegate to him Eurasian models and plans of the Eurasian Project”. Nevertheless, Dugin was genuinely critical when Putin was allegedly friendly to the United States or Russian liberal economists.

After the Orange Revolution in Ukraine, Dugin apparently obtained funding from Putin’s Presidential Administration to establish the Eurasian Youth Union. It was one of several pro-Kremlin youth movements that were created to oppose the largely imaginary threat of a “colour revolution” in Russia. However, the Eurasian Youth Union was not the most successful of these movements and the Kremlin preferred to invest more money in the Nashi movement rather than Dugin’s initiative. The Kremlin clearly perceives Dugin’s ideas as useful. By being regularly present in the public sphere, Dugin and other Russian rightwing extremists extending the boundaries of a legitimate space for illiberal narratives make Russian society more susceptible to Putin’s authoritarianism.

In a 2007 interview for Russian internet TV, Dugin pompously stated: “My discourse rules, my ideas rule. […] Sure, there are wide circles, layers of people between me and the power structures. [These people] dilute […] my condensed idea of Eurasian geopolitics, conservative traditionalism and other ideals which I defend and develop, to which I dedicate a lot of my work – they create a diluted version of these. Eventually, this version reaches the power structures and they draw upon it as something self-evident, obvious, and easily accessible. […] That’s why I think that Putin is increasingly becoming Dugin. At any rate, he pursues a plan that I elaborate, in which I invest my energy, my whole life. […] In the 1990s, my discourse seemed mad, eccentric […] today our ideas are taken for granted.”

Dugin’s words, obviously, cannot be taken at face value, but his ideas evidently entered the mainstream political thinking.

Imperialist gambleDugin actively supported Russia’s invasion of Georgia in 2008 and craved for the complete occupation of that country. For Dugin, the war in Georgia was an existential battle against Atlanticism: “If Russia decides not to enter the conflict […] that will be a fatal choice. It will mean that Russia gives up her sovereignty” and “We will have to forget about Sevastopol.” Naturally, Dugin fanatically supported the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and urged Putin to invade south-eastern Ukraine. It was a dream that he had been cherishing since the 1990s: “The sovereignty of Ukraine represents such a negative phenomenon for Russian geopolitics that it can, in principle, easily provoke a military conflict. […] Ukraine as an independent state […] constitutes an enormous threat to the whole Eurasia and without the solution of the Ukrainian problem, it is meaningless to talk about continental geopolitics.”

In the spring of 2014, Dugin seemed to have reconsidered the Neo-Eurasianist idea of western Ukraine belonging to Mitteleuropa. He argued that, “in its liberationist battle march” not only will Russia not stop at Crimea, central and western Ukraine, but will aim at “liberating central and western Europe from Atlanticist invaders”. His inflammatory writings attracted a lot of media attention, and since his ideological narrative overlapped with the Kremlin’s actions in Ukraine he was called “Putin’s brain”.

However, the increased media attention eventually rebounded on Dugin and the management of Moscow State University – probably in agreement with, or even under pressure from, the Kremlin – decided not to extend his employment contract. Dugin accused Russia’s liberal “fifth column” of conspiring against him, but the reasons for his falling out of favour with the Kremlin are most likely different.

First of all, as in the case of Russia’s war in Georgia, Dugin perceived the invasion of Ukraine as the Kremlin’s fundamental duty. He claimed that if Putin did not fulfil his “historical Eurasianist mission”, then the Kremlin would betray Russia. Thus, Putin would turn into an enemy of Russian ultranationalists who would have a right to attack his regime. No matter whether Putin planned or did not plan to occupy Ukraine, the Kremlin could not accept such an ultimatum.

Second, there is a political circle close to the Kremlin that – being anti-American and imperialistic – considers Dugin’s connections to the western European farR Right and evidently non-Russian fascist sources of Neo-Eurasianism as damaging the “anti-fascist” posture of Moscow.

Third, Putin never revealed that his foreign policy was guided by any kind of ideology and always stressed the “pragmatic” nature of the Russian approach to the West. Had Putin named any particular guiding ideology, then he would have been challenged intellectually – a battle that he would have been doomed to lose. Moreover, the assumption that the Kremlin was following Dugin’s ideas made Putin predictable. At the end of the day, Dugin has put forward a very clear, “ready-to-use” geopolitical strategy, but it is Putin’s unpredictability that plays to his advantage in foreign relations.

Despite the fact that the Kremlin has clearly distanced itself from Dugin, this does not mean that his Neo-Eurasianism has been condemned. But does Putin support Neo-Eurasianism? There are obvious similarities between Dugin’s and Putin’s narratives: anti-westernism, expansionism and the rejection of liberal democracy among them. However, it would be wrong to suggest that any of these or similar ideological elements are exclusive to either Putin or Dugin, as they have been embedded in Russian politics for more than a century.