The Original Russia ConnectionFelix Sater has cut deals with the FBI, Russian oligarchs, and Donald Trump. He’s also quite a talker.By Andrew Rice

Photo-illustration by Bobby Doherty

August 3, 2017

10:50 am

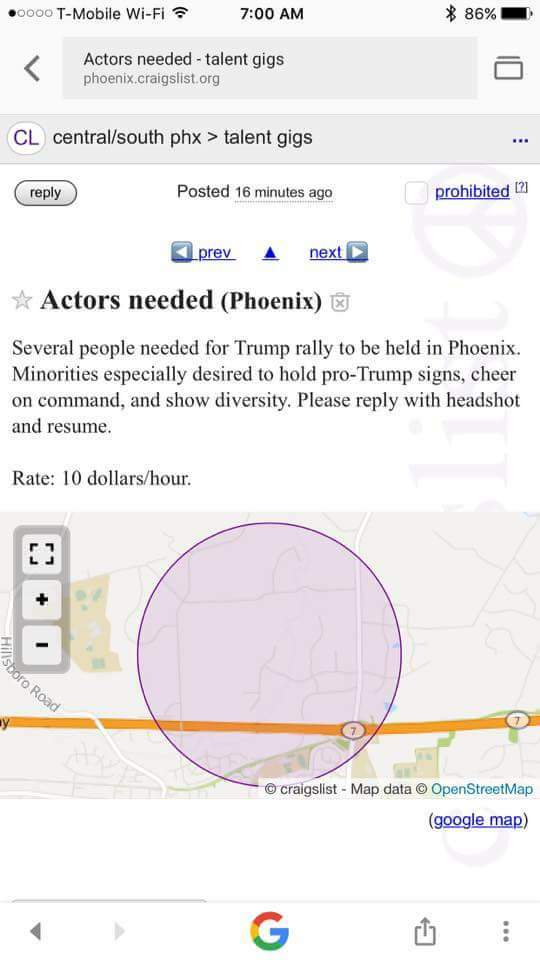

On June 19 in a courtroom in Downtown Brooklyn, a federal judge took up the enigmatic case of an individual known as John Doe. According to the heavily redacted court record, Doe was an expert money launderer, convicted in connection with a stock swindle almost 20 years ago. But many other facts about his strange and sordid case remained obscured. The courtroom was filled with investigative journalists from numerous outlets along with lawyers petitioning to unseal documents related to the prosecution. “This case,” argued John Langford, a First Amendment specialist from Yale Law School who represented a Forbes editor, implicates an “integrity interest of the highest order.” The public had a right to know more about Doe’s history, Langford argued, especially in light of “the relationship between the defendant in this case and the president of the United States.”

John Doe’s real name, everyone in the courtroom knew, was Felix Sater. Born in Moscow and raised in Brooklyn, Sater was Donald Trump’s original conduit to Russia. As a real-estate deal-maker, he was the moving force behind the Trump Soho tower, which was built by developers from the former Soviet Union a decade ago. Long before Donald Trump Jr. sat down to talk about kompromat with a group of Kremlin-connected Russians, Sater squired him and Ivanka around on their first business trip to Moscow. And long before their father struck up a bizarrely chummy relationship with Vladimir Putin, Sater was the one who introduced the future president to a byzantine world of oligarchs and mysterious money.

Sater was a canny operator and a colorful bullshitter, and there were always many rumors about his background: that he was a spy, that he was an FBI informant, that he was tied to organized crime. Like a lot of aspects of the stranger-than-fiction era of President Trump, these stories were both conspiratorial on their face and, it turns out, verifiably true. Langford read aloud from the transcript of a 2011 court hearing, only recently disclosed, in which the Justice Department acknowledged Sater’s assistance in investigations of the Mafia, the Russian mob, Al Qaeda, and unspecified “foreign governments.” A prosecutor once called Sater, in another secret proceeding, “the key to open a hundred different doors.” Many were wondering now whether he could unlock the truth about Trump and Russia.

Related Stories

How Trump’s Russian Business Ties Led to Don Jr. Meeting a Kremlin-Linked Lawyer

Report: Trump’s Lawyer Involved With Secret Plan to Lift Russian Sanctions

In the universe of what the president has called, with telling self-centrism, his “satellite” associates, Sater spins in an unmapped orbit. The president has said under oath that he “really wouldn’t know what he looked like” if they were in the same room. (For the record, Sater is 51 years old and olive-complexioned, with heavy-lidded eyes.) Yet their paths have intersected frequently over the years. Most recently, in February, the Times reported that Sater had attempted to broker a pro-Russian peace deal in Ukraine, handing a proposal to Michael Cohen, the president’s personal attorney, to pass to Michael Flynn, who was then still the national-security adviser. Both Cohen and Flynn are now reported to be under scrutiny by the FBI, in connection with special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation of Russia’s election interference and Trump’s campaign.

If there really is a sinister explanation for the mutual affinity between Trump and Putin, it almost certainly traces back to money. The emissaries who met with Don Jr., promising damaging information on Hillary Clinton, came through the family’s business relationship with property developer Aras Agalarov, who had been trying to build a Trump tower in Moscow. Both congressional investigators and the special counsel are reportedly zeroing in on the finances of Trump and associates, looking for suspicious inflows. On July 20, Bloomberg News reported that the special counsel had taken over a preexisting money-laundering investigation launched by ousted U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara and was said to be examining, among other things, the development of the Trump Soho.

As a convicted racketeer with murky ties to the Mafia, law enforcement, intelligence agencies (both friendly and hostile), various foreign oligarchs, and the current president of the United States, Sater has become an obsession of the many investigators — professional and amateur — searching for Trump’s Russia connection. Since the election, especially in the more feverish precincts of the internet, he has been the subject of constant speculation, which has at times been contradictory. Was he the missing link to the Kremlin? (“Trump, Russia, and a Shadowy Business Partnership,” read the headline of a recent column by Trump biographer Tim O’Brien.) Or could he be Mueller’s inside man? (“Will a Mob-Connected Hustler Be the First Person to Spill the Beans to the FBI on Trump’s Russian Ties?” asked a story on the lefty site Alternet.) Could he be playing both sides?

At least one clue to the answer, Sater’s pursuers suspect, may be found in the records of his closed criminal case — which just so happened to have been overseen by one of the top prosecutors working on Mueller’s investigation. Judge Pamela Chen listened as the various attorneys advocating for disclosure made impassioned arguments, drawing on Supreme Court precedents, the Pentagon Papers, and even the possibility of “fraud by President Trump.” But when it came time for federal prosecutors to make the case for continued confidentiality, citing concerns for Sater’s safety and the possible disclosure of sensitive details about government operations, Chen closed the courtroom to the public.

The key documents in Sater’s case remain sealed. His lips, however, are another matter.

Trump with Sater in 2005. Photo: Cyrus McCrimmon/The Denver Post via Getty Images

For an international man of mystery, Sater can be quite talkative. Over the past few months, I’ve reached out to him regularly by phone and email, and every once in a while, he has responded. He would vent about how he was “tired of being kicked in the balls” over long-ago offenses, by reporters investigating his ties to Trump. Then he asked what I wanted to know.

“What do you do for a living?” I asked.

“I am the epitome of the word ‘the deal guy,’ ” Sater replied.

People who know Sater told me he shares some character traits with Trump, a man for whom he professes unabashed affection. He tends to talk grandiosely, if not always entirely truthfully; he can play the coarse outer-borough wiseguy or the charming raconteur. Most of all, like the man he orbits, he has a transactional view of the universe — anything can be brokered. “I work on deals,” Sater told me. “Deals in real estate, liquid natural gas, medicine. I am currently working on bringing a — don’t laugh, do not laugh — a cure for cancer using stable isotopes.” He said he found the technology through a former real-estate partner, who had met a scientist, who was now testing it.

“I own a significant piece of it for doing the work,” Sater said. “I’ll find investors, and eventually, God willing, we will be able to deliver the cure for cancer. But as my lawyer, Robert Wolf, says, ‘Felix, if you announce that you’ve found the cure for cancer, tomorrow’s papers are going to be, ‘Trump’s Gangster-Related Ex-Partner Looking to Steal Money from Medicaid.’ That’ll be the headline for the cure for cancer.”

Sater said a lot of things like that, maybe just to be playful. He would joke sardonically about the latest additions to his Google search results, which yielded story after story about his entrepreneurial ventures, live and defunct, the two dozen or so lawsuits relating to various personal and business disputes, his curious presence at Trump Tower (the Federal Election Commission recorded a $120 purchase of campaign merchandise there on July 21, 2016, the day before WikiLeaks started releasing hacked Democratic Party emails) and even the Orthodox religious movement he belongs to, which was the subject of a breathless Politico exposé headlined “The Happy-Go-Lucky Jewish Group That Connects Trump and Putin.” “It was like, my rabbi from Chabad flying back and forth and smuggling secret messages in his ass or something,” Sater said. He scornfully dismissed the whole notion that he might be some kind of middleman between Trump and Russia. Then he would confide just enough about himself to keep the conversation interesting.

When I asked Sater how he first met Trump, he replied, “No comment on anything related to the president of the United States.” He savored a delicious pause. “But back in ’96, I rented the penthouse suite of 40 Wall Street,” a Trump-owned skyscraper. (A contemporary court record confirms he had an office there.) A few years later, Sater started doing deals to license Trump’s name for real-estate projects.

“How did I get to Donald?” Sater asked. “I walked in his door and told him, ‘I’m gonna be the biggest developer in New York, and you want to be my partner.’ ”

In reality, Sater’s route to Trump’s office was anything but direct. His family emigrated from the Soviet Union when he was 7. He grew up on Surf Avenue in Coney Island. As a boy, he said, he used to sell the Forward on the boardwalk. His father, Mikhail — “a big strapping fellow,” Sater said, who was once a boxer — worked as a cabdriver. At some point, the elder Sater got involved in organized crime, running a long-term extortion racket in Brighton Beach with a Genovese-family soldier. (He would end up pleading guilty to extortion charges in 2000.)

After a few years of college, Felix Sater found his way to Wall Street in the late 1980s. Brokerage houses then had retail operations that sold stocks over the phone, and Sater started out as a cold-caller. He worked his way up through several firms, including Gruntal, a freewheeling brokerage that did a lot of business with Michael Milken. (One of Sater’s colleagues there was Steve Cohen, the hedge-fund billionaire who recently dodged insider-trading charges.) A friend, Sal Lauria, later wrote in a Wall Street crime memoir, The Scorpion and the Frog, that Sater was a sly salesman and a sharp dresser who would routinely spend thousands of dollars on designer suits. They frequented nightclubs and celebrity parties. At one such event, Lauria wrote, they encountered Trump, who sent a bodyguard over to obtain the phone numbers of their wives.

They laughed off that advance, but Lauria wrote that Sater could be “a hothead” when provoked. One night in 1991, when Sater was in his mid-20s, they were out at a bar in midtown when Sater got into a drunken argument over a woman and ended up slashing another man’s face with a broken margarita glass. He was convicted of assault, served a year in prison, and was barred from selling securities.

Sater moved over to the shady side of Wall Street, establishing a firm called White Rock, which engaged in illegal pump-and-dump schemes. The firm would secretly acquire blocks of penny stocks; then, its brokers would hype them to suckers over the phone. Sater and Lauria had personal ties to mobsters, and the firm received protection from Mikhail Sater’s associate in the Genovese family. Using an alias, “Paul Stewart,” Felix Sater laundered fraud proceeds through a labyrinthine network of Caribbean shell companies, Israeli and Swiss bank accounts, and contacts in New York’s Diamond District. He moved in the same bucket-shop demimonde as Jordan Belfort, the crooked trader portrayed in The Wolf of Wall Street.

“Jordan was a stone-cold little bitch, and everybody knew it,” said Sater, who claims that Belfort was actually nothing special as a salesman. “Jordan picked up 90 percent of it from everybody else and turned it into his own movie. I have had 27 producers approach me already to sell my life’s work, and I’m sitting here going, ‘Why?’ So in the first two minutes of the movie some director could show me doing coke out of a hooker’s ass?” (Through a representative, Belfort said he had no recollection of Sater.)

In the mid-1990s, the Mafia’s involvement in stock manipulation caught the attention of law enforcement. Feeling the heat, Sater decided to get out of the illegal business, starting a seemingly legitimate investment company in his penthouse office at 40 Wall Street. He explored opportunities back in Russia, which was going through its chaotic post-Communist privatization process. He and his partners moved to Moscow, where they presented themselves as New York bankers. “We were dealing with ex-KGB generals and with the elite of Russian society,” Lauria wrote.

One night, Sater told me, he went to dinner with a contact that he assumes was affiliated with the GRU, the Russian military-intelligence agency, where he was introduced to another American doing business in Moscow, Milton Blane. “There’s like eight people there,” Sater said, “and he’s sizing me up all dinner long. As I went to take a piss, he followed me into the bathroom and said, ‘Can I have your phone number? I’d like to get together and talk to you.’ ” Blane, who died last year, was an arms dealer. According to a government disclosure made 13 years ago in response to a Freedom of Information Act query, Blane had a contract with the Defense Department to procure “foreign military material for U.S. intelligence purposes.” Sater says the U.S. wanted “a peek” at a high-tech Soviet radar system. “Blane sat down with me and said, ‘The country needs you,’ ” Sater said.

This was the beginning of what Sater claims were many years of involvement with intelligence agencies. He says he developed contacts at secret Russian military installations known as closed cities. “I was working for the U.S. government, risking my life in Russia,” Sater said. “Picture what they would have done if they were to have caught me in closed military cities — a little Jewish boy who gave up his passport and now was trying to buy the highest secret shit on behalf of the Americans. You think anybody would ever find me again?”

Meanwhile, back in New York, the FBI was looking for Sater. The bureau’s investigation into the Mafia and Wall Street had caught a break when someone neglected to pay the rent for a locker at a Manhattan Mini Storage facility on Spring Street. The management opened it up, found three guns, and called the police. The locker also held a cache of papers stuffed into a box and a gym bag: financial records that documented Sater’s money-laundering activities. The FBI launched an investigation called Operation Street Cleaner, targeting Sater and his co-conspirators.

At first, Lauria wrote, they hoped that Sater’s spying might earn them a “free ride” for their financial crimes. In addition to the radar system, Sater has publicly claimed that he provided intelligence on some Stinger missiles floating around Afghanistan, as well a phone number for Osama bin Laden. The FBI was not satisfied, however, so the fugitives returned to the U.S., where they pleaded guilty and became government witnesses. (Andrew Weissmann, the supervising prosecutor who approved Sater’s cooperation agreement in December 1998, would go on to become a top deputy to Mueller on the Russia investigation.) In 2000, Operation Street Cleaner culminated in the arrests of 19 people, including several alleged mobsters, who were charged with cheating investors out of $40 million.

Sater would continue to work with the FBI for years afterward in the hope of reducing his eventual sentence. Sater provided assistance “of an extraordinary depth and breadth,” a prosecutor later said in a closed hearing, on matters that ran “a gamut that is seldom seen.” After the September 11 attacks, as the FBI and CIA scrambled to respond to the threat of terrorism and Islamist insurgency, intelligence about black-market arms dealing suddenly became extremely valuable. Loretta Lynch, who oversaw Sater’s case as the U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of New York, later testified during her confirmation process to become Attorney General that Sater’s work for the FBI and other agencies involved “providing information crucial to national security.”

Sater was skilled at deciphering financial fraud, and as is often the case, the same things that made him a successful criminal — his ingratiating charm, his street smarts, his ability to see all the angles — made him a very useful government asset. He engaged in undercover work, making “surreptitious recordings,” according to an unsealed court-hearing transcript. “He was always looking for the next big person to get connected to,” said a former law-enforcement officer who worked on Sater’s case.

So long as Sater continued to assist the FBI, the bureau left him free to do business. He kept up his wealthy lifestyle with his family, living on a beachfront lane in the moneyed enclave of Sands Point on the Long Island Sound — the model for East Egg in The Great Gatsby. He was finished on Wall Street, but real estate is far less regulated. Sometime around 2000, Sater got to know a neighbor, Tevfik Arif, an oleaginous former Soviet official from Kazakhstan. Arif and his family made money in the chromium business after the fall of communism, and had interests in hotels and construction in Turkey. He and Sater went into business together, calling their firm the Bayrock Group.

Bayrock leased office space on the 24th floor of Trump Tower, one floor below the headquarters of the Trump Organization. At this time, it wasn’t too difficult for a company without a reputation to approach Trump, whose business career was in a relative lull between his 1990s crash and his big comeback with The Apprentice. The Bayrock office was staffed with an assortment of eye-catching women, many of them from Eastern Europe. One attracted the attention of a Trump Organization leasing agent, who started paying calls to the office. He provided an introduction to Trump’s development team, a former Bayrock executive says. Soon Sater was in the boss’s office. In a 2008 deposition taken in connection with Trump’s unsuccessful libel lawsuit against his biographer O’Brien, Sater testified that the companies interacted “on a constant basis” and that he frequently popped in to visit Trump himself for “real-estate conversations.”

Sater says he convinced Trump to license his name to Bayrock developments in Florida and Arizona. Such deals, a major component of Trump’s business over the past two decades, allowed him to avoid issues of creditworthiness, which posed a problem because of his previous defaults, while capitalizing on his primary asset, his celebrity. Trump described the licensing business as “really risk-free.” If a project succeeded, he could bray triumphantly and collect fees, and if it failed, he could walk away, disclaiming responsibility. For Sater, the partnership offered an opportunity to leverage Trump’s name. In the deposition, he called this his “Trump card,” and he said he played it at every possible opportunity. “My competitive advantage is, anybody can come in and build a tower,” Sater said. “I can build a Trump tower, because of my relationship with Trump.”

When asked about Sater in his own deposition, Trump swore that “nobody knows anything about this guy.” Sater’s federal case was still secret, and he had taken to spelling his name “Satter” to avoid incriminating search results. But even a cursory background check would have revealed his earlier assault conviction and a 1998 Businessweek article about his involvement in stock fraud headlined “The Case of the Gym Bag That Squealed.” Sal Lauria, despite his lack of real-estate experience, also went to work for Bayrock as an independent contractor.

Sater played the role of the jet-setting deal-maker, entertaining lavishly, traveling constantly, jumping on a helicopter to Cannes when he felt the traffic from a nearby airport was moving too slowly. Joshua Bernstein, one of Sater’s subordinates, later asserted under oath that he and Lauria would often joke about being “white-collar criminals” and claimed that Sater had threatened to kill him, once on the day of the office Christmas party while wielding a pair of scissors. “He would say things like that regularly throughout the firm,” Bernstein testified. Another Bayrock associate in Arizona claimed in a lawsuit, later settled and sealed, that Sater once threatened to torture him and leave him dead in a car trunk. (Sater vehemently denies threatening either man and says the lawsuit allegations were financially motivated.)

In 2005, Sater and Trump embarked on their most ambitious joint project: the Trump Soho. The site of the development — a parking lot on Spring Street — happened to be directly across the street from the storage facility that had been Sater’s previous undoing. Trump took a very active interest, handling negotiations over construction contracts and promoting the building on The Apprentice. Trump received a 15 percent ownership stake in return for contributing his name and expertise, as well as a potential cut of development fees and an ongoing deal to manage the hotel. Another 3 percent of the building was allotted to Trump’s children Ivanka and Don Jr., who were just beginning to involve themselves in the family company. They worked closely with Bayrock, particularly Don, who played a deal-making role, traveling with Sater to explore other prospective projects.

Sater also tried to take the Trump brand abroad. Bayrock proposed deals in Ukraine, Poland, and Turkey. In Moscow, Sater identified a site for a high-rise Trump tower. He later testified that Donald Trump personally asked him to chaperone Don and Ivanka when they traveled to the Russian capital to explore the opportunity.

In September 2007, Trump, Arif, and Sater unveiled Trump Soho. The real-estate bubble was about to burst, but Bayrock was inflated, at least temporarily, by a group of people with even worse market timing: Icelandic bankers. Lauria managed to broker a deal with the FL Group, an investment group run by a long-haired “Viking raider.” The Icelandic fund agreed to invest $50 million in Bayrock, offering Arif and Sater a potentially lucrative payout. In December 2007, though, the Times reporter Charles Bagli published a scoop, revealing many details of Sater’s criminal history. Bayrock’s partners were upset; Sater complained in a leaked email that Trump was treating the scandal as “an opportunity to try and get development fees for himself.” Sater was quickly and quietly forced out of the company.

When the market crashed, Bayrock did, too, and none of the foreign projects came to fruition. Condo sales at the Trump Soho dried up, although Ivanka and Don Jr. continued to boast, falsely, that a majority of the building’s units had been sold. In August 2010, a group of Trump Soho buyers sued, claiming the building’s marketing was “fraudulent.” (Trump and his co-defendants agreed to settle with the buyers, refunding nearly $3 million.) That September, Arif was arrested on human-trafficking charges in Turkey after police broke up an alleged sex party he was holding on a yacht attended by Russian prostitutes and business associates, including a Kazakh billionaire whom Bayrock once listed as a financial backer. (Arif was later acquitted at trial.)

Sater, meanwhile, dropped out of public view. As Bayrock was imploding, he formed a new company called Swiss Capital, also on the 24th floor of Trump Tower. He shifted his activities to Europe, working on coal and oil deals in Kazakhstan, hotel projects in France and Switzerland. He spent an extended period in London, pursuing developments with Sergei Polonsky, a flamboyant builder from St. Petersburg who — like all of Russia’s new billionaires — maintained warm relations with Vladimir Putin. But Polonsky soon went bust and ran afoul of the Russian state. He was later arrested at his Cambodian island retreat, deported home, and convicted of embezzlement.

This whole time, Sater had been working on the side with the FBI. He has claimed that he was “building Trump Towers by day and hunting bin Laden by night.” When his Orthodox synagogue, Chabad of Port Washington, named him its Man of the Year, the congregation’s rabbi gave a speech recounting how Sater had told him many things about his past, few of which he really believed, until one day he was invited to a private event at a federal building in New York. “I get there, and to my amazement I see dozens of U.S. intelligence officers from all the various three-letter intelligence agencies,” the rabbi said. “They’re taking turns, standing up one after the other, offering praise for Felix, praising him as an American hero for his work and his assistance at the highest levels of this country’s national-security interest.”

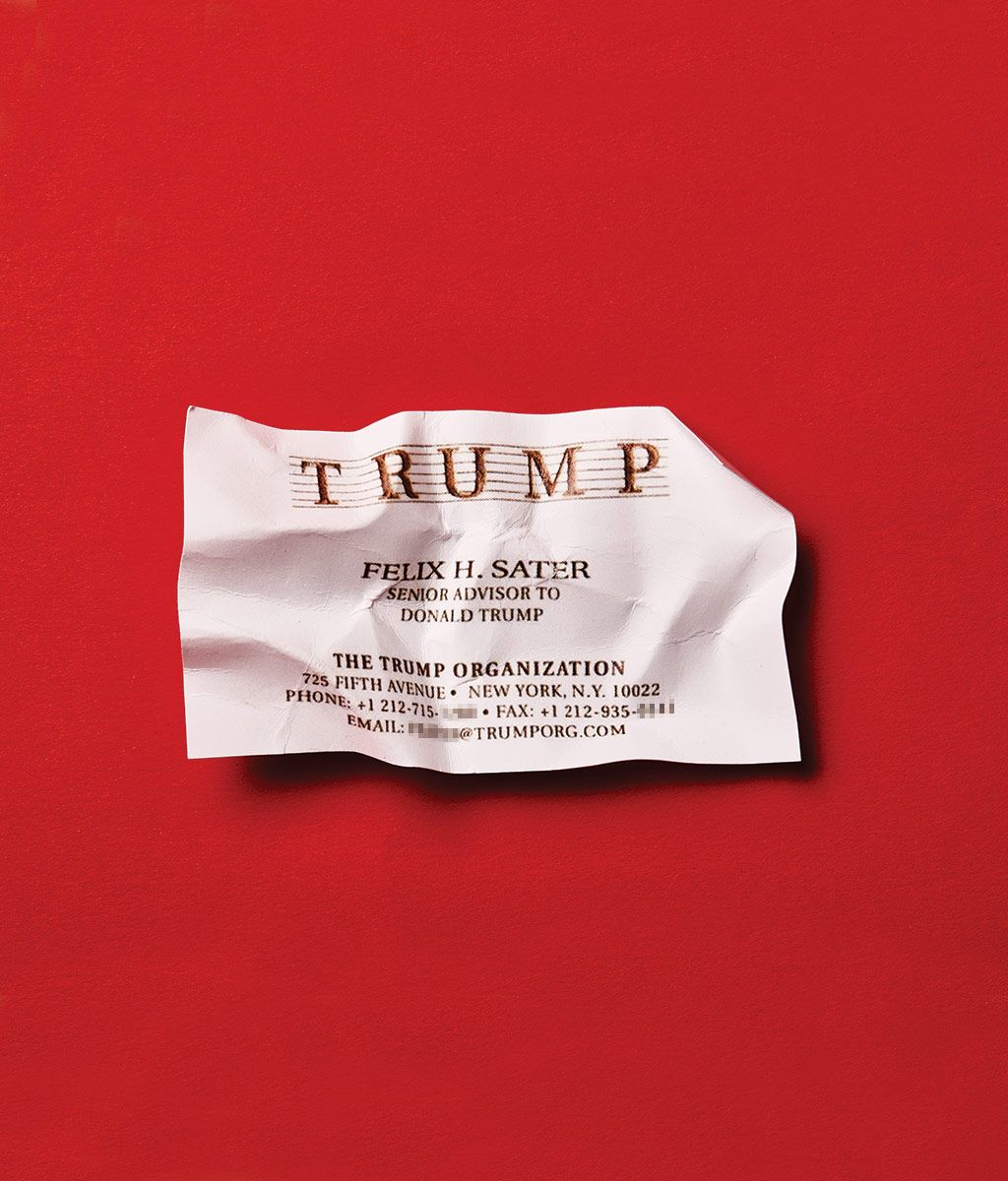

Sater’s decade of undercover work finally ended in October 2009, when he was sentenced for his securities fraud at a secret proceeding in Brooklyn. (He was given no jail time and a $25,000 fine.) Around the same time, Sater paid a visit to Trump Tower. “I stopped up to say hello to Donald, and he says, ‘You gotta come here,’ ” Sater told me. Though the Trump Organization has contended it never formally employed Sater, he had business cards that identified him as a “senior advisor” to Trump. “Donald wanted me to bring deals to him,” Sater said. “Because he saw how many I put on the table at Bayrock.”

He said Trump’s willingness to take him on, even after discovering his criminal past, was indicative of his character. “I know you’re gonna be able to spin it as ‘He doesn’t care and will do business even with gangsters,’ ” Sater said to me. “Wouldn’t it also show extreme flexibility, the ability not to hold a grudge, the ability to think outside the box, and it’s okay to be enemies one day and friends the next?”

None of the real-estate deals Sater was trying to drum up for Trump materialized, and he drifted away from the company within a year. Since then, Trump’s memory of Sater has grown foggier. “I never really understood who owned Bayrock,” he testified in 2011. Two years later, he abruptly cut off a BBC television interview when Sater’s name came up. In 2015, in response to questions from the Associated Press, Trump replied, “Felix Sater, boy, I have to even think about it.” In legal proceedings related to Bayrock’s failed ventures, Trump has contended he had little personal involvement in any of his licensing projects. “In general, [you] go into a deal, you think a partner is going to be good,” Trump said in a 2013 deposition. “It happens with politics. It happens with everything. You vote for people, they turn out to be no good.”

I stopped up to say hello to Donald, and he says, ‘You gotta come here,’ ” Sater said. “Donald wanted me to bring deals to him.

Sater continued to move in New York real-estate circles, though he tried to keep a lower profile. He was part of an insular Russian-American business community, and during the oil and gas boom earlier this decade, he was well positioned to act as a middleman between New York developers and Russian oligarchs who were trying to reinvest their fortunes in property. “He had access to high-net-worth individuals in Russia and the U.S.,” said a business associate of Sater’s. Sater has claimed he was working on a Trump-branded real-estate deal with a Russian real-estate developer in Moscow as late as 2015. (Agalarov signed a letter of intent to build a Trump tower in Moscow around the same time, but Sater denied this was the same project.)

One person whom Sater dealt with extensively was a Swiss-based investor named Ilyas Khrapunov, whose family was involved in banking and politics in Kazakhstan. Starting in 2011, with Sater’s assistance, Khrapunov and his family members invested in, among other things, a shopping mall outside Cincinnati, a residential complex in Syracuse, an apartment building on West 52nd Street, and three condos in the Trump Soho. According to a lawsuit filed by the firm of Boies Schiller Flexner, which is coordinating a global asset-recovery effort on the behalf of a Kazakh bank, the money for Khrapunov’s real-estate investments came from billions looted from the bank and a municipal government. In July, the Financial Times reported that Sater was assisting in a money-laundering investigation of the Khrapunovs, in which it said the FBI has taken an interest. (The paper’s sources said Sater was “being paid handsomely for his assistance.”) U.S. laws, which exempt real-estate transactions from certain anti-money-laundering regulations, have long made if possible for American developers to profit from the proceeds of crime and political corruption. The FBI is reported to be looking into whether Trump and other figures close to him might have engaged in such behavior, but money-laundering investigations are notoriously arduous, and proving intentional wrongdoing is especially difficult when the money comes from criminal activity in a foreign country.

Much of what is publicly known about Sater traces in one way or another to a seven-year legal battle, which has taken place largely out of public view. Years before anyone cared much about Donald Trump’s ledger books, Jody Kriss, Bayrock’s former director of finance, went to see a lawyer named Frederick Oberlander. Kriss thought he had been cheated out of money that Bayrock owed him. He told Oberlander, a specialist in arcane tax issues, all about the company’s dealings, including the FL Group transaction. Oberlander has a shambling manner and talks like a mad scientist. (Among other things, he told me that he studied astrophysics at a NASA institute and had taught computer science at Yale, that he had worked on nuclear submarines, that he used to be a competitive weightlifter, that he made a fortune in software development, that he once traded derivatives and sniffed out Bernie Madoff before anyone, and that he went into tax law, at which he was brilliant, because he “thought it would be fun.”) Oberlander told Kriss he thought that Bayrock’s finances looked fishy.

Oberlander also made contact with a second former Bayrock employee, Joshua Bernstein, the one who claimed Sater had threatened him. He had been fired and was suing over compensation. He possessed a hard drive containing thousands of internal documents and emails, as well as copies of several documents from Sater’s stock-fraud case, including a confidential government presentencing report, detailing his secret cooperation. Oberlander appears to have seen the documents as a tool to prod Bayrock toward a large settlement. “I am so not kidding this is not a game,” Oberlander wrote Bernstein in an email. “My job is to shake the living daylights out of them.”

In May 2010, Kriss filed suit in federal court, alleging that “tax evasion and money laundering are the core of Bayrock’s business model.” An enormous complaint, written by Oberlander and illustrated with arrow-filled flowcharts and snippets of incriminating internal emails, purported to describe a wildly complex racketeering conspiracy. It claimed that Bayrock had been “largely a mob-owned and operated business,” that it had engaged in fraud, that the FL Group transaction has been structured to evade taxes, and that much of the money had been siphoned off by insiders. (The complaint alleged some $10 million was allotted to “repay hidden interests in Russia and Kazakhstan.”) Oberlander attached Sater’s presentencing report as an exhibit. In a letter to Sater’s lawyer, Oberlander likened the suit to a “tactical nuclear device,” bound to yield massive press attention.

Sater’s lawyers later claimed that the presentencing document amounted to “an extortionist’s Holy Grail,” exposing him to retribution from the Mafia. Oberlander argued that the First Amendment gave him the right to alert the public, especially in light of Sater’s continuing business activities. The courts came down hard on Sater’s side. The civil case against Bayrock was immediately sealed, and the judge who presided over Sater’s old stock-fraud case, saying “something very bad and perhaps despicable was done,” ordered that Oberlander and Bernstein hand over the offending documents. (Bernstein later settled his claim against Bayrock and is no longer involved in the case.)

For the next few years, in closed proceedings, Oberlander would fight an increasingly fanatical legal battle, filing numerous suits against Bayrock, its lawyers and accountants, and the man referred to only as “John Doe.” He has faced both civil contempt proceedings and a criminal investigation related to his alleged defiance of court orders regarding the dissemination of sealed information. (No charges have ever been brought.) “Frederick Oberlander has a history of overstepping legal boundaries,” a Bayrock spokeswoman said, citing the contempt proceedings. “He has filed a string of meritless legal actions in hopes of a financial windfall.”

Whatever Oberlander’s motivations were to begin with, he has managed to drag many compromising facts into the open, including the FBI’s apparent blindness to Sater’s business dealings and millions in income from Bayrock. (In 2011, well after his sentencing, the IRS hit Sater with $460,000 in tax liens relating to the period he worked for Bayrock, which he did not pay off for two years.) Even after Kriss removed him as his lawyer, Oberlander continued to fight on in a variety of legal venues, including in a case in which he is suing on behalf of allegedly defrauded New York State taxpayers.

His lawsuit does not name Trump as a defendant, but the litigation has already damaged the president by revealing the dodgy goings-on at Bayrock, which, even if not criminal, certainly look suspicious, given the many questions surrounding Trump’s financial links to Russia. Two sources said Oberlander has provided information to Senate investigators.

“Donald Trump’s projects with Bayrock were financed with the proceeds of transnational crime,” Oberlander claimed when I met him for lunch one day in April. “He knew, and he continued to take the money.” (The Trump Organization did not respond to a request for comment.) Oberlander described elaborate machinations involving secret agreements and misdirection, most of which appeared to be based on inference rather than the documentary evidence in the public domain. “You want to understand how it works? I show you or you’re obviously going to fail,” he snapped, when I expressed confusion about an intricate diagram he was sketching on a paper tablecloth. “You think way too much more of your intellect than you should. And you can quote me on that!”

In our chats, Sater called Oberlander a “nut job” and said the lawsuits were “pure extortion.” Last December, a federal judge denied a motion to dismiss Kriss’s civil fraud, racketeering, and conspiracy claims against Sater and other Bayrock executives. (The parties are now in settlement talks.) “It overshadows my life. And then with Donald becoming president and obviously me being the major Russian mafioso that I am,” he said sarcastically, “it’s just been a disaster for my life. A complete disaster.”

Despite his protests, Sater seemed to revel, just a bit, in all the speculation swirling around him. Last August, in the middle of the presidential campaign, Sater was introduced, via a mutual friend, to a veteran political fixer named Robert Armao. “I looked him up,” Armao told me, “and I said, ‘This is an interesting man.’” They met for a meal, where Sater regaled him with tales about Trump, and predicted he would win the presidency, for sure. Armao was impressed. “Felix Sater knows everybody, everywhere,” he said.

Armao, once a political aide to Nelson Rockefeller, has represented foreign leaders as a communications adviser and does business in the energy industry. Sater told him he coveted the “wonderful Rolodex” he had built over decades. Over the next few months, he would ask Armao to act as his intermediary on a number of matters, including enlisting Armao’s assistance in brokering an energy deal to refurbish Ukraine’s aging nuclear reactors.

They met again for breakfast at the St. Regis Hotel, a block south of Trump Tower, on October 7, the day the Obama administration issued its first urgent warning about Russian election interference, WikiLeaks published the first batch of John Podesta’s emails, and Trump’s vulgar Access Hollywood tape appeared. This time, Sater brought along a friend: Andrii Artemenko, a Ukrainian opposition politician. The nuclear deal appeared to be just the beginning of their plans, which would end up entangling the White House. “I think they had visions of kingmaking, and making Artemenko president of Ukraine,” Armao said. “Then you’d really be in business.”

“Artemenko is a politician who, like every politician, wants to become president,” Sater said. “So he came to me.” Though they started off talking about nuclear reactors, and averting another Chernobyl, Trump’s election appeared to open up an even more ambitious opportunity. “I got friendly with Artemenko over that deal, and he said, ‘Look, it’s killing me, we’ve got people dying every day between all the bombings and killings.’ I mean they’re killing kids over there. ‘There’s a new administration coming in, you got access to the administration. I know how to end the war in eastern Ukraine.’

“He goes, that’s the idea, let’s end the war. Let’s get peace going. Peace sounds good, right? How does the word peace not work?”

In January, Artemenko returned to the United States to attend Trump’s inauguration, bringing with him a Putin-friendly peace proposal, which called for a referendum to approve Russia’s occupation of Crimea in return for the end of hostilities in eastern Ukraine. (The plan also called for deploying propaganda to undermine Ukraine’s current president, a Putin adversary.) “I think it sounds like a good idea,” Sater said. “Politically, it would be an opportunity to break the situation that is currently going on with Russia. ’Cause I am a very firm believer that Vlad the Terrible — no matter how poised he is and how well he controlled himself in the Oliver Stone interview — that crazy fucker has got 10,000 nuclear warheads pointed at us. Not a good guy to get into a pissing match with.

“So I figured, hey, things could work out all around, and probably give Donald, who wants to get on better relations with Putin, an opportunity to break this logjam. So I picked up the phone, and called Michael Cohen.”

Cohen, one of Trump’s personal attorneys, had known Sater since they were teenagers. He met Artemenko and Sater at a hotel on Park Avenue, and they gave him a sealed envelope containing the plan. The New York Times reported that Cohen said he had hand-delivered the envelope to Flynn at the White House. (Cohen later denounced the Times story as “fake news.”) After it was exposed, the peace initiative was scuttled and Trump’s opponents seized on fresh evidence that — preposterous as it might seem — Sater still had enough pull with the president to dabble in diplomacy. “A Big Shoe Just Dropped,” wrote the liberal blogger Josh Marshall, who has continued to enthusiastically delve into Sater’s role in what he calls the “Trump-Russia money channel.”

Since then, shoe after shoe has clunked to the floor, in a cacophonous cascade of ever-more-damaging disclosures. “I know there is a huge movement to find the there there,” Sater said in June. “I got it. But unfortunately, I’m not going to be the one.” He said he would be happy to be summoned to speak to Mueller or congressional investigators. “God bless them if they do,” he said. “We could talk about bin Laden and Al Qaeda and cyber-crime convictions and operations of over fucking 12 years, no problem.”

He couldn’t resist telling me, though, that something big was brewing. “In about the next 30 to 35 days,” he told me, “I will be the most colorful character you have ever talked about. Unfortunately, I can’t talk about it now, before it happens. And believe me, it ain’t anything as small as whether or not they’re gonna call me to the Senate committee.”

This was before the news of Don Jr.’s fateful Trump Tower meeting came out. Still, it was already clear that Mueller was shifting his attention toward Trump’s family business, and many were wondering if Sater, who sang so beautifully for the FBI before, might have another big number to perform. Lately, something about Mueller’s investigation seems to have truly alarmed the president. Rattled by its focus on his finances, the president has sent signals that he might fire the special counsel and has openly discussed issuing preemptive pardons. The extremity of Trump’s reaction has only heightened suspicions he has something truly damning to hide. And if anyone outside the president’s immediate orbit knows what that is, one could imagine it would be Sater.

Sater laughed off such theories. “The next three years of hearings about Trump and Russia will yield absolutely nothing. I know the man, they didn’t collude,” he said. “Did a bunch of meetings happen? Absolutely. The people on the Trump team who had any access to the Russians wanted to be first in and be the guys that ran the whole détente thing. Michael Flynn wanted to be the détente guy, and then [Paul] Manafort, I’m sure, wanted to be the détente guy. Shit, I wanted to be the détente guy, why not? But was it really a conspiracy between Putin and Donald to get him elected? A little bit of a stretch.”

“When was the last time you talked to the president of the United States?” I asked.

For once, the deal guy had nothing to offer.

http://nymag.com/daily/intelligencer/20 ... ation.html