ZombiesFirst published Mon Sep 8, 2003; substantive revision Thu Mar 17, 2011

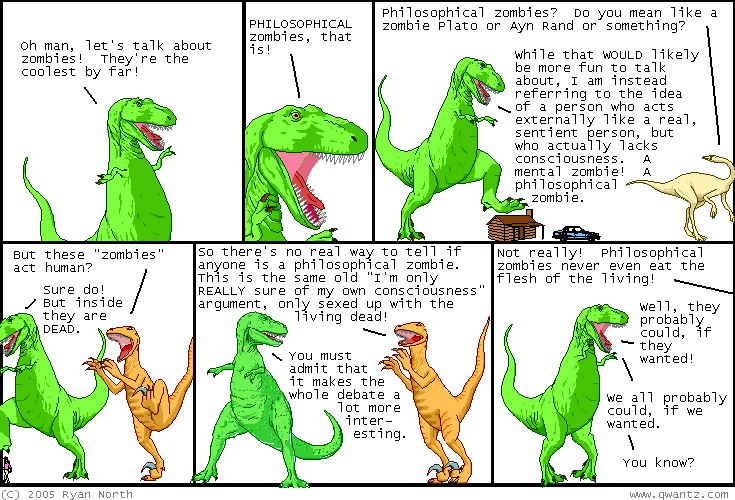

Zombies in philosophy are imaginary creatures used to illuminate problems about consciousness and its relation to the physical world. Unlike those in films or witchraft, they are exactly like us in all physical respects but without conscious experiences: by definition there is ‘nothing it is like’ to be a zombie. Yet zombies behave just like us, and some even spend a lot of time discussing consciousness.

Few people think zombies actually exist. But many hold they are at least conceivable, and some that they are possible. It is argued that if zombies are so much as a bare possibility, then physicalism is false and some kind of dualism is true. For many philosophers that is the chief importance of the zombie idea. But the idea is also of interest for its presuppositions about the nature of consciousness and how the physical and the phenomenal are related. Use of the zombie idea against physicalism also raises more general questions about relations between imaginability, conceivability, and possibility. Finally, zombies raise epistemological difficulties: they reinstate the ‘other minds’ problem.

[...]

1. The idea of zombiesDescartes held that non-human animals are automata: their behavior is wholly explicable in terms of physical mechanisms. He explored the idea of a machine which looked and behaved like a human being. Knowing only seventeenth century technology, he thought two things would unmask such a machine: it could not use language creatively, and it could not produce appropriate non-verbal behavior in arbitrarily various situations (Discourse V). For him, therefore, no machine could behave like a human being. He concluded that explaining distinctively human behavior required something beyond the physical: an immaterial mind, interacting with processes in the brain and the rest of the body. (He had a priori arguments for the same conclusion, one of which foreshadows the ‘conceivability argument’ discussed below.) If he is right, there could not be a world physically like the actual world but lacking such minds: human bodies would not work properly. If we suddenly lost our minds our bodies might continue to run on for a while: our hearts might continue to beat, we might breathe while asleep and digest food; we might even walk or sing in a mindless sort of way (so he implies in his Reply to Objections IV). But without the contribution made by minds, behavior could not show characteristically human features. So although Descartes did everything short of spelling out the idea of zombies, the question of their possibility did not arise for him. The nearest thing was automata whose behavior was easily recognizable as not fully human.

In the nineteenth century scientists began to think that physics was capable of explaining all physical events that were explicable at all. It seemed that every physical effect has a physical cause: that the physical world is ‘closed under causation’. The developing science of neurophysiology was set to extend such explanations to human behavior.

But if human behavior is explicable physically, how does consciousness fit into the story? One response — physicalism (or materialism) — is to insist that it is just a matter of physical processes. However, the phenomena of consciousness are hard to account for in those terms, and some thinkers concluded that nonphysical items must be involved. Given the causal closure of the physical, they were also forced to conclude that consciousness has no effects on the physical world. On this view human beings are

‘conscious automata’, as T. H. Huxley put it: all physical events, human behavior included, are explicable in terms of physical processes; and the phenomena of consciousness are causally inert by-products (see James 1890, Chapter 5). It eventually became clear that this view entailed there could be purely physical organisms exactly like us except for lacking consciousness. G. F. Stout (1931) argued that if epiphenomenalism (the more familiar name for the ‘conscious automaton’ theory) is right,

it ought to be quite credible that the constitution and course of nature would be otherwise just the same as it is if there were not and never had been any experiencing individuals. Human bodies would still have gone through the motions of making and using bridges, telephones and telegraphs, of writing and reading books, of speaking in Parliament, of arguing about materialism, and so on. There can be no doubt that this is prima facie incredible to Common Sense (138f.).

What Stout describes in this passage and finds prima facie incredible is a zombie world: an entire world whose physical processes are closed under causation (as the epiphenomenalists he was attacking held) and exactly duplicate those in the actual world, but where there are no conscious experiences.

Similar ideas were current in discussions of physicalism in the 1970s. As a counterexample to the psychophysical identity theory there was an ‘imitation man’, whose ‘brain-states exactly paralleled ours in their physico-chemical properties’ but who felt no pains and saw no colors (Campbell 1970). It was claimed that zombies are a counterexample to physicalism in general, and arguments were devised to back up the intuition that they are possible (Kirk 1974a, 1974b). Other kinds of systems were envisaged which behaved like normal human beings, or were even functionally like human beings, but lacked the ‘qualia’ we have (Block 1980a, 1980b, 1981; Shoemaker 1975, 1981). (Qualia are those properties of experiences or of whole persons by which we are able to classify experiences according to ‘what they are like’ — what it is like to smell roasting coffee beans, for example. Even physicalists can consistently use this expression, although unlike dualists they take qualia to be physical. The most systematic use of the zombie idea against physicalism is by David Chalmers (1996), some of whose contributions to the debate will be discussed below.

If zombies are to be counterexamples to physicalism, it is not enough for them to be behaviorally and functionally like normal human beings: physicalists can accept that merely behavioral or functional duplicates of ourselves might lack qualia. Zombies must be like normal human beings in all physical respects, with the physical properties that physicalists suppose we have. (For the use of a different kind of zombies in epistemology, see Lyons 2009.) This requires them to be subject to the causal closure of the physical, which is why their supposed lack of consciousness is a challenge to physicalism. If, instead, their behavior could not be explained physically, physicalists would point out that in that case we have no reason to bother with the idea: there is plenty of evidence that our movements actually are explicable in physical terms, as the original epiphenomenalists realized (see e.g. Papineau 2002).

The usual assumption is that none of us is actually a zombie, and that zombies cannot exist in our world. The central question, however, is not whether zombies can exist in our world, but whether they, or a whole zombie world (which is sometimes a more appropriate idea to work with), are possible in some broader sense.

[...]

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/zombies/