Moderators: Elvis, DrVolin, Jeff

seemslikeadream wrote:Jack R did you hear Jonathan Alter talking about his new book Promise? He tells a story about Obama having to actually break up a fist fight between Barney Frank and Hank Paulsen

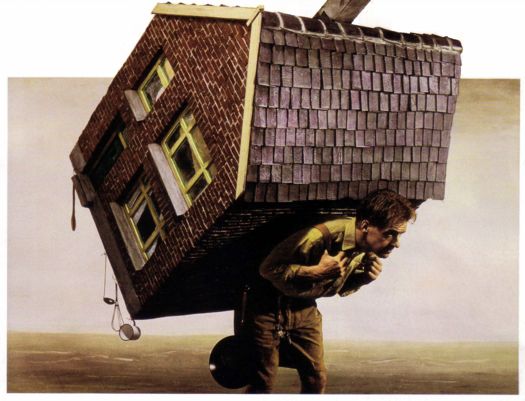

anothershamus wrote:This guy know how the feelings are running! Take a look at that chart and the USA is Wayyy up in the right hand corner. The larger the inequity the greater the rage! He may be on to something. This first part is good too about the nobility giving up their jewellery and privileges paying more in taxes, do you think that would happen here in the USA, not if they had to give up their private jets and $1500.00 lunches!

Link here: http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2010/05/schama-are-the-guillotines-being-sharpened.htmlSaturday, May 22, 2010

Schama: Are the Guillotines Being Sharpened?

Simon Schama tonight warns in the Financial Times that revolutionary rage is close to the boiling point in Europe and the US :

Historians will tell you there is often a time-lag between the onset of economic disaster and the accumulation of social fury. In act one, the shock of a crisis initially triggers fearful disorientation; the rush for political saviours; instinctive responses of self-protection, but not the organised mobilisation of outrage…

Act two is trickier. Objectively, economic conditions might be improving, but perceptions are everything and a breathing space gives room for a dangerously alienated public to take stock of the brutal interruption of their rising expectations. What happened to the march of income, the acquisition of property, the truism that the next generation will live better than the last? The full impact of the overthrow of these assumptions sinks in and engenders a sense of grievance that “Someone Else” must have engineered the common misfortune….At the very least, the survival of a crisis demands ensuring that the fiscal pain is equitably distributed. In the France of 1789, the erstwhile nobility became regular citizens, ended their exemption from the land tax, made a show of abolishing their own privileges, turned in jewellery for the public treasury; while the clergy’s immense estates were auctioned for La Nation. It is too much to expect a bonfire of the bling but in 2010 a pragmatic steward of the nation’s economy needs to beware relying unduly on regressive indirect taxes, especially if levied to impress a bond market with which regular folk feel little connection. At the very least, any emergency budget needs to take stock of this raw sense of popular victimisation and deliver a convincing story about the sharing of burdens. To do otherwise is to guarantee that a bad situation gets very ugly, very fast.

Schama knows this terrain cold; his chronicle of the French Revolution, Citizens, made clear what a bloody affair it was. Even so, his account in the Financial Times in some key respects understates the degree of dislocation suffered by many in advanced economies. Schama depicts the crisis-induced change as merely the end of rising expectations, but the shock is deeper than that.

Severe financial crises result in a permanent decline in the standard of living. For some citizens, that has come through contracts being reneged, in particular, pension cuts. Other people see their savings in tatters and have no realistic prospect for being able to fund their retirement. And for many of these individuals, the odds of finding continuing, reasonably paid work are low. Even before unemployment soared, people over 40 face poor job prospects. The idea that the middle aged cohort can earn back losses to their nest eggs is wishful thinking. And the young are not much better off. New graduates also face a hostile job market. Worse, students often went into debt to finance their education, believing the mantra that it was an investment.

And many of the societies suffering these financial shocks have already suffered a great deal of erosion of their underlying support structures. Even before the crisis, in the US and other advanced economies, social bonds have eroded in a remarkably short period of time, roughly a generation and a half. Job tenures are short; employees and employers have little loyalty to each other. Ties to communities are weak. Many families have two working parents, so career and parenting demands leave little time to participate in local organizations. Advanced technology frequently offers an easier leisure outlet than trying to coordinate schedules with time (or financially) stressed friends. But marriage and families are also not the haven they once were, given high divorce rates.

One oft unrecognized factor is that alienation and social stress are directly related to income inequality. This is hardly a new finding, but it seldom gets media coverage in the plutocratic US. And it has concrete, measurable costs. As Michael Prowse explained in the Financial Times:

…..if you look for differences between countries, the relationship between income and health largely disintegrates. Rich Americans, for instance, are healthier on average than poor Americans, as measured by life expectancy. But, although the US is a much richer country than, say, Greece, Americans on average have a lower life expectancy than Greeks. More income, it seems, gives you a health advantage with respect to your fellow citizens, but not with respect to people living in other countries….

Once a floor standard of living is attained, people tend to be healthier when three conditions hold: they are valued and respected by others; they feel ‘in control’ in their work and home lives; and they enjoy a dense network of social contacts. Economically unequal societies tend to do poorly in all three respects: they tend to be characterised by big status differences, by big differences in people’s sense of control and by low levels of civic participation….

Unequal societies, in other words, will remain unhealthy societies – and also unhappy societies – no matter how wealthy they become. Their advocates – those who see no reason whatever to curb ever-widening income differentials – have a lot of explaining to do.

Yves here. If you look at broader indicators of social well being, you see the same finding: greater income inequality is associated with worse outcomes. From a presentation by Kate Pickett, Senior lecturer at the University of York and author of The Spirit Level, at the INET conference in April:

Note in particular where Japan sits on the chart. Some readers have argued that the US has little to fear from deflation and a protracted period of near-zero growth, since Japan is orderly and prosperous-looking, despite its relative decline. But Japan was and is the most socially equal major economy, and during its crisis, it observed the Schama prescription of sharing the pain. The US, the UK, and to a lesser degree, Europe, have done the exact reverse, with both the bank rescues and austerity measures effectively a transfer from ordinary citizens to financiers.

As James Lardner pointed out in the New York Review of Books in June 2007, even before the wheels started coming off the economy, the social contract in the US was pretty frayed, but a concerted propaganda campaign PR effort promoted the fiction that it was the best of all possible worlds:

To gain their political ends, the robber barons and monopolists of the Gilded Age were content with corrupting officials and buying elections. Their modern counterparts have taken things a big step further, erecting a loose network of think tanks, corporate spokespeople, and friendly press commentators to shape the way Americans think about the economy…. the new communications apparatus wants us to believe that our economic wellbeing depends almost entirely on the so-called free market—a euphemism for letting the private sector set its own rules. The success of this great effort can be measured in the remarkable fact that, despite the corporate scandals and the social damage that these authors explore; despite three decades of deregulation and privatization and tax-and-benefit-slashing with, as the clearest single result, the relentless rise of economic inequality to levels so extreme that since 2001 “the economy” has racked up five straight years of impressive growth without producing any measurable income gains for most Americans—even now, discussions of solutions or alternatives can be stopped almost dead in their tracks by mention of the word government.

Yves here. Having weakened faith in government and made considerable progress towards creating a social Darwinist paradise of isolated individuals pitted against each other, the oligarchs may be about to harvest a whirlwind.

JackRiddler wrote:justdrew: My responses to your ideas, which are in bold.This is the over-centralization that so many fear, I think rightly, as inflexible, unaccountable, "command economy." Banks should be public, serve the public, and not be designed for profit or plow profits into a public pool. But not just one, or it will turn into the most corrupt mess.

- one bank.

inflexible, yes... but it doesn't need to flex, the words for it from a positive perspective are: predictable and reliable. there's still be a plethora of regional offices and local branches, which can all have somewhat local culture, but at the end of the day, all the banking activities simply follow the rule book aka The Bank Manual.Yeah, that's more the idea - but not one bank. Banking as a public utility.

- one capital holding pool. to which all profits and losses accrue.

This way everyone with deposits get's paid interest based on the performance of all the banks investments. The whole point being to ensure that cash flows. To paraphrase Dune, The Cash Must Flow.

I sometimes think it'd be nice if any given enterprise ran it's operations on a purely cash-flow basis, accumulating reserves, held as cash, to fund it's operations and continuance, rather than relying on debt. but this would actually be very bad because it would tie up vast sums of cash in people's reserve vaults. So the money has to be held somewhere that it can be used by others until it's needed by the depositor. The safest and most efficient way to do this seems to me to be one vast holding account from which the money is 'put to work'. all profits and losses accrue to the Primary Fund and determine the monthly interest earned for depositors. The banks only takes enough from profits to fund it's operations.More or less the idea. Many banks, but one set of rules. The most important relates to interest. It should never be more than enough to cover the bank's real expenses, say something like 2 percent above inflation and no compound interest. Eliminating compound interest would be a great blow for humankind. (Fees for late payment Another possibility is that the bank creates and pays itself a one-time expense charge for a loan, but caps on total lending have to be agreed beforehand. Lending criteria should be rational and uniform. If you can pay a mortgage according to the formula (and your actual income and assets are checked), you get it - and everyone gets the same term. Exchanges, conversions and renovations of existing building stock are encouraged over new building, since there is enough.

- one rule book that governs all operations of the one bank.

I think depositors would still get compound interest but the rate would be dependent on the actual performance of the banks 'putting the money to work' efforts. weekly or monthly interest payment cycles would be sufficient.Another reason for multiple banks is multiple functions according to who uses it, and protecting one from the failure of the other. At the least: consumer (handles payroll for public employees, mortgages, individual accounts and credit), small business and farm, and development and large business. These are organized at the state level so they respond to local needs but especially the development banks must agree on lending limits nationally in a consensus process based on per capita numbers and a rational development plan. It won't be pretty, but it won't be the centralized planning/command economy that is unresponsive to local input.

- one place to go for a loan... the bank.

There could be no failures and since everyone is operating from the same Bank Manual - getting a loan is purely a function of the numbers brought to the function. The formula says give 'em the money or don't. People with bankruptcy history can try to start over via the bank lotterying off a limited number of second chance credit lines every year to those with good ideas but past failures.

as to lending limits, the one bank simply could not lend more money than it has on hand, on the other hand, it would need to "put the money to work" that it does have on hand, otherwise that cash is just sitting there not doing anything. A majority of deposits will be withdrawn at any given moment to meet depositors needs to spend (payroll, inventory acquisition, paying rent, etc) so it's hard to say how much money at any given time would be in the bank searching for work... A big chunk of that would be going to fund Our government's operation and other collectively required projects (environmental remediation, sustainable infrastructure revolution ,etc).Why should the bank become the automatic employment agency? I'd favor something like this in railway building or (this is a growing need) disaster response.

- the bank is over staffed. accommodating high turnover. working at the bank becomes a default job for those with no where else to work. most of the jobs are easy to learn due to everything being based on the rule book. all branches operate the same.

There also needs to be some acknowledgement that an enormous amount of reproductive work that is necessary for the whole to function doesn't get paid. Do we want an authority checking over the quality of the dish-washing?! Hell no! Where this should head is a basic wage. The idea of paying everyone including effectively paying some people not to work is very hard for our culture to swallow, but needs to be comprehended at some point because we need to actually shrink our labor hours and use of resources, and stop seeing economic "growth" as a good thing.

well, The Bank wouldn't be the only source of easily get-able jobs. The goal here is primarily to prevent Bank operators from becoming a cloistered special class that require vast pay and theoretically rare talents no one else has. Every job from clerk to comptroller has a couple 'intendants' (here meaning designated successors) shadowing and learning the ropes at any moment.

I completely agree that there needs to be a default guaranteed paycheck for everyone. It wouldn't be anything fancy though and most people would no doubt prefer to go to various part time jobs at least to gain basic skills and move up into more demanding jobs that pay better as possible.Completely open accounts would be another radical idea that I regard as a necessity for any rational democracy but that would be very difficult to learn. I mean, everyone's going to be complaining about some different part of the balance sheets until the enormous initial problems are worked out. This is where utopias generally fail and what I see as the primary obstacle to this one: getting the buy-in from the people who have to invest so much of themselves into untried change, enough so that they can tolerate inevitable failures starting out and with sufficient consensus to overcome the opposition who will still want the old system.

- the jobs are relatively simple, being governed only and totally by the rule book.

- adherence to the rule book is simple to verify as all activities are openly logged, the bank has no secrets.

individual account balances could be kept semi-secret as the open reporting could replace identifying info with an annonymized unique id. the main thing to open up here is all the internal working of the bank, so the audit wing and independent audits can be guaranteed to be able to go back and see exactly who did what when in any circumstance.Isn't that perhaps the biggest issue - how is this national consensus forged. Now that we are past the fiat declarations of what constitutes reality, priorities and agenda by the executive branch and the captains of capital, we're stuck in a sort of endless meeting. I'd be for the equivalent of an economic congress alongside the political one. Bank executives at the state levels are appointed for set terms by the state legislatures and by bodies involved in economic life such as labor and management, a system akin to the German works council. They send representatives to the national coordinating body. The mission of that body has to be made explicit as the necessary conversions in energy, transport and farming to sustain our population on this planet - as well as full employment in rational, meaningful work.

- new procedures for the rule book are openly discussed and implemented by national consensus from time to time. "innovations" are carefully considered and modeled and thought about for a long time before implemented in the live economy.

yeah, this bit could get complicated. some percent of loans would need to be speculative (not based on nearly certain cash flows) that can be paid back if things work out but are lost if the creditors plan doesn't work out. This part of bank operations might replace much of the venture capital 'industry'. Complicated derivative type stuff is just off the table and will never be implemented. Not exactly sure how this would be done, but I kinda like your idea of having a sort of congress made up of appointees and elected people. An apolitical modeling service would be needed as well, kind of a GAO for the Bank's Rule Evolution Process.As a starting idea - this provides the money supply. At minimal interest.

- all governmental cash outflow is financed by loans from the bank, paid back from tax revenue, which is adjusted as required automatically to service the debt.

Is this the start of a constitutional convention for the political economy, on a thread?

would be nice to get something started.

These banking reforms also go along side my stock market reforms posted elsewhere. The main design goal is to simplify simplify simplify. People should be able to understand how their financial systems work and they should work in a predictable and reliable fashion.

I'm not sure if any of this can be implemented by anything other than a benevolent dictatorship employing a minimum of sentimentality. The hope would be that the transition back to democratic norms, limited to prevent elected officials from wrecking the system that was just built, within a generation. While dictatorial in many respects, popularity is still needed. Population regions would still elect reps to a consultative and advisory and investigative body, but the power to get hard things done quickly would have to exist somewhere. Accountability can be enforced by a broad presumption that failures always result in dismissal from any position of power and legal charges brought for failure to execute one's duties or criminal charges as needed. Intendants are always on hand and up to speed to step in if an authority holder has to be removed.

It may be the only way to head off total fascism is to get in front of the forces pushing toward it and hijack the authoritarian upwelling to a good end rather than letting it become an end-in-itself, controlled by the existing oligarchs and their captive proles.

but hey, maybe it won't come to that.

Rating Agency Data Aided Wall Street in Deals

April 23, 2010

By GRETCHEN MORGENSON and LOUISE STORY

One of the mysteries of the financial crisis is how mortgage investments that turned out to be so bad earned credit ratings that made them look so good.

One answer is that Wall Street was given access to the formulas behind those magic ratings — and hired away some of the very people who had devised them.

In essence, banks started with the answers and worked backward, reverse-engineering top-flight ratings for investments that were, in some cases, riskier than ratings suggested, according to former agency employees.

The major credit rating agencies, Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s and Fitch, drew renewed criticism on Friday on Capitol Hill for failing to warn of the dangers posed by complex investments like the one that has drawn Goldman Sachs into a legal whirlwind.

But while the agencies have come under fire before, the extent to which they collaborated with Wall Street banks has drawn less notice.

The rating agencies made public computer models that were used to devise ratings to make the process less secretive. That way, banks and others issuing bonds — companies and states, for instance — wouldn’t be surprised by a weak rating that could make it harder to sell the bonds or that would require them to offer a higher interest rate.

But by routinely sharing their models, the agencies in effect gave bankers the tools to tinker with their complicated mortgage deals until the models produced the desired ratings.

“There’s a bit of a Catch-22 here, to be fair to the ratings agencies,” said Dan Rosen, a member of Fitch’s academic advisory board and the chief of R2 Financial Technologies in Toronto. “They have to explain how they do things, but that sometimes allowed people to game it.”

There were other ways that the models used to rate mortgage investments like the controversial Goldman deal, Abacus 2007-AC1, were flawed. Like many in the financial community, the agencies had assumed that home prices were unlikely to decline. They also assumed that complex investments linked to home loans drawn from around the nation were diversified, and thus safer.

Both of those assumptions were wrong, and investors the world over lost many billions of dollars. In that Abacus investment, for instance, 84 percent of the underlying bonds were downgraded within six months.

But for Goldman and other banks, a road map to the right ratings wasn’t enough. Analysts from the agencies were hired to help construct the deals.

In 2005, for instance, Goldman hired Shin Yukawa, a ratings expert at Fitch, who later worked with the bank’s mortgage unit to devise the Abacus investments.

Mr. Yukawa was prominent in the field. In February 2005, as Goldman was putting together some of the first of what would be 25 Abacus investments, he was on a panel moderated by Jonathan M. Egol, a Goldman worker, at a conference in Phoenix.

The next month, Mr. Yukawa joined Goldman, where Mr. Egol was masterminding the Abacus deals. Neither was named in the Securities and Exchange Commission’s lawsuit, nor have the rating agencies been accused of wrongdoing related to Abacus.

At Goldman, Mr. Yukawa helped create Abacus 2007-AC1, according to Goldman documents. The safest part of that earned an AAA rating. He worked on other Abacus deals.

Mr. Yukawa, who now works at PartnerRe Asset Management, a money management firm in Greenwich, Conn., did not return requests for comment.

Goldman has said it will fight the accusations from the S.E.C., which claims Goldman built the Abacus investment to fall apart so a hedge fund manager, John A. Paulson, could bet against it. And in response to this article, Goldman said it did not improperly influence the ratings process.

Chris Atkins, a spokesman for Standard & Poor’s, noted that the agency was not named in the S.E.C.’s complaint. “S.& P. has a long tradition of analytical excellence and integrity,” Mr. Atkins said. “We have also learned some important lessons from the recent crisis and have made a number of significant enhancements to increase the transparency, governance and quality of our ratings.”

David Weinfurter, a spokesman for Fitch, said via e-mail that rating agencies had once been criticized as opaque, and that Fitch responded by making its models public. He stressed that ratings were ultimately assigned by a committee, not the models.

Officials at Moody’s did not respond to requests for comment.

The role of the rating agencies in the crisis came under sharp scrutiny Friday from the Senate’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. Members grilled representatives from Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s about how they rated risky securities. The changes to financial regulation being debated in Washington would put the agencies under increased supervision by the S.E.C.

Carl M. Levin, the Michigan Democrat who heads the Senate panel, said in a statement: “A conveyor belt of high-risk securities, backed by toxic mortgages, got AAA ratings that turned out not to be worth the paper they were printed on.”

As part of its inquiry, the panel made public 581 pages of e-mail messages and other documents suggesting that executives and analysts at rating agencies embraced new business from Wall Street, even though they recognized they couldn’t properly analyze all of the banks’ products.

The documents also showed that in late 2006, some workers at the agencies were growing worried that their assessments and the models were flawed. They were particularly concerned about models rating collateralized debt obligations like Abacus.

According to former employees, the agencies received information about loans from banks and then fed that data into their models. That opened the door for Wall Street to massage some ratings.

For example, a top concern of investors was that mortgage deals be underpinned by a variety of loans. Few wanted investments backed by loans from only one part of the country or handled by one mortgage servicer.

But some bankers would simply list a different servicer, even though the bonds were serviced by the same institution, and thus produce a better rating, former agency employees said. Others relabeled parts of collateralized debt obligations in two ways so they would not be recognized by the computer models as being the same, these people said.

Banks were also able to get more favorable ratings by adding a small amount of commercial real estate loans to a mix of home loans, thus making the entire pool appear safer.

Sometimes agency employees caught and corrected such entries. Checking them all was difficult, however.

“If you dug into it, if you had the time, you would see errors that magically favored the banker,” said one former ratings executive, who like other former employees, asked not to be identified, given the controversy surrounding the industry. “If they had the time, they would fix it, but we were so overwhelmed.”

Case Said to Conclude Against Head of A.I.G. Unit

Prosecutors Ask if 8 Banks Duped Rating Agencies

May 12, 2010

By LOUISE STORY

The New York attorney general has started an investigation of eight banks to determine whether they provided misleading information to rating agencies in order to inflate the grades of certain mortgage securities, according to two people with knowledge of the investigation.

The investigation parallels federal inquiries into the business practices of a broad range of financial companies in the years before the collapse of the housing market.

Where those investigations have focused on interactions between the banks and their clients who bought mortgage securities, this one expands the scope of scrutiny to the interplay between banks and the agencies that rate their securities.

The agencies themselves have been widely criticized for overstating the quality of many mortgage securities that ended up losing money once the housing market collapsed. The inquiry by the attorney general of New York, Andrew M. Cuomo, suggests that he thinks the agencies may have been duped by one or more of the targets of his investigation.

Those targets are Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, UBS, Citigroup, Credit Suisse, Deutsche Bank, Crédit Agricole and Merrill Lynch, which is now owned by Bank of America.[b]

The companies that rated the mortgage deals are Standard & Poor’s, Fitch Ratings and Moody’s Investors Service. Investors used their ratings to decide whether to buy mortgage securities.

Mr. Cuomo’s investigation follows an article in The New York Times that described some of the techniques bankers used to get more positive evaluations from the rating agencies.

Mr. Cuomo is also interested in the revolving door of employees of the rating agencies who were hired by bank mortgage desks to help create mortgage deals that got better ratings than they deserved, said the people with knowledge of the investigation, who were not authorized to discuss it publicly.

Contacted after subpoenas were issued by Mr. Cuomo’s office notifying the banks of his investigation, representatives for Morgan Stanley, Credit Suisse, UBS and Deutsche Bank declined to comment. Other banks did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

In response to questions for the Times article in April, a Goldman Sachs spokesman, Samuel Robinson, said: [b]“Any suggestion that Goldman Sachs improperly influenced rating agencies is without foundation. We relied on the independence of the ratings agencies’ processes and the ratings they assigned.” [b]

Goldman, which is already under investigation by federal prosecutors, has been defending itself against civil fraud accusations made in a complaint last month by the Securities and Exchange Commission. The deal at the heart of that complaint — called Abacus 2007-AC1 — was devised in part by a former Fitch Ratings employee named Shin Yukawa, whom Goldman recruited in 2005.

At the height of the mortgage boom, companies like Goldman offered million-dollar pay packages to workers like Mr. Yukawa who had been working at much lower pay at the rating agencies, according to several former workers at the agencies.

Around the same time that Mr. Yukawa left Fitch, three other analysts in his unit also joined financial companies like Deutsche Bank.

In some cases, once these workers were at the banks, they had dealings with their former colleagues at the agencies. In the fall of 2007, when banks were hard-pressed to get mortgage deals done, the Fitch analyst on a Goldman deal was a friend of Mr. Yukawa, according to two people with knowledge of the situation.

Mr. Yukawa did not respond to requests for comment. A Fitch spokesman said Thursday that the firm would cooperate with Mr. Cuomo’s inquiry.

Wall Street played a crucial role in the mortgage market’s path to collapse. Investment banks bundled mortgage loans into securities and then often rebundled those securities one or two more times. Those securities were given high ratings and sold to investors, who have since lost billions of dollars on them.

Banks were put on notice last summer that investigators of all sorts were looking into their mortgage operations, when requests for information were sent out to all of the big Wall Street firms. The topics of interest included the way mortgage securities were created, marketed and rated and some banks’ own trading against the mortgage market.

The S.E.C.’s civil case against Goldman is the most prominent action so far. But other actions could be taken by the Justice Department, the F.B.I. or the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission — all of which are looking into the financial crisis. Criminal cases carry a higher burden of proof than civil cases. Under a New York state law, Mr. Cuomo can bring a criminal or civil case.

His office scrutinized the rating agencies back in 2008, just as the financial crisis was beginning. In a settlement, the agencies agreed to demand more information on mortgage bonds from banks.

Mr. Cuomo was also concerned about the agencies’ fee arrangements, which allowed banks to shop their deals among the agencies for the best rating. To end that inquiry, the agencies agreed to change their models so they would be paid for any work they did for banks, even if those banks did not select them to rate a given deal.

Mr. Cuomo’s current focus is on information the investment banks provided to the rating agencies and whether the bankers knew the ratings were overly positive, the people who know of the investigation said.

A Senate subcommittee found last month that Wall Street workers had been intimately involved in the rating process. [b]In one series of e-mail messages the committee released, for instance, a Goldman worker tried to persuade Standard & Poor’s to allow Goldman to handle a deal in a way that the analyst found questionable.

The S.& P. employee, Chris Meyer, expressed his frustration in an e-mail message to a colleague in which he wrote, “I can’t tell you how upset I have been in reviewing these trades.”

“They’ve done something like 15 of these trades, all without a hitch. You can understand why they’d be upset,” Mr. Meyer added, “to have me come along and say they will need to make fundamental adjustments to the program.”

At Goldman, there was even a phrase for the way bankers put together mortgage securities. The practice was known as “ratings arbitrage,” according to former workers. The idea was to find ways to put the very worst bonds into a deal for a given rating. The cheaper the bonds, the greater the profit to the bank.

The rating agencies may have facilitated the banks’ actions by publishing their rating models on their corporate Web sites. The agencies argued that being open about their models offered transparency to investors.

But several former agency workers said the practice put too much power in the bankers’ hands. “The models were posted for bankers who develop C.D.O.’s to be able to reverse engineer C.D.O.’s to a certain rating,” one former rating agency employee said in an interview, referring to collateralized debt obligations.

A central concern of investors in these securities was the diversification of the deals’ loans. If a C.D.O. was based on mostly similar bonds — like those holding mortgages from one region — investors would view it as riskier than an instrument made up of more diversified assets. Mr. Cuomo’s office plans to investigate whether the bankers accurately portrayed the diversification of the mortgage loans to the rating agencies.

Gretchen Morgenson contributed reporting.

Big TARP Banks Not Helping Small Businesses: Warren

Published: Thursday, 13 May 2010 | 8:29 AM ET

The government's bank bailout program may have helped big financial institutions weather the credit crisis but has failed in getting money to small businesses, the head of the commission overseeing the fund told CNBC.

Elizabeth Warren called it "infuriating" that the Troubled Asset Relief Program has not achieved its objective in funneling some of the $700 billion in appropriations to small businesses.

A report the commission released Thursday found that big-bank lending portfolios to small businesses dropped 9 percent from 2008 to 2009, more than double the 4.1 decrease of its overall lending portfolio.

"Two out of every three new jobs created in America come out of a small business. Fifty percent of the private work force is in small business," Warren said in an interview. "If they don't have access to credit it's not only a problem to them now, but they can't help fund the recovery."

The report found that several Treasury Department TARP initiatives to get money to small businesses have proven ineffective, in part because banks were not required to lend the billions they had received in capital through the program.

RELATED LINKS

Crisis Hit Minority Mortgage Access

Were Ratings Agencies Duped?

"Some borrowers looked to community banks to pick up the slack, but small banks remained strained by their exposure to commercial real estate and other liabilities," the commission's executive summary said. "Unable to find credit, many small businesses have had to shut their doors, and some of the survivors are still struggling to find adequate financing."

The Treasury Department said in a statement that it agrees more needs to be done to get capital to small businesses.

Warren said she hopes a new program, the proposed Small Business Lending Fund, will help address the problem. The $30 billion package still needs congressional approval.

But she also warned that it "may not be enough" and the consequences could be dire if the lending disparity isn't evened out.

"If we play that out over time and there's more money available to big businesses and less money available to small businesses, we really end up tilting the playing field...and that's not going to help us in the recovery," she said.

© 2010 CNBC.com

JackRiddler wrote:I would also think: Violence in the media does not directly cause any violence, but celebrating riches contributes to greed and financial cheating.

One thing I can say for sure is that watching MTV Cribs is more likely to make me violent (and greedy, and dishonest) than any amount of violent films. MTV Cribs is one of the best arguments for full-scale revolution I've ever seen in my life, and I hope I never have to see a better one.

Every normal man must be tempted at times to spit upon his hands, hoist the black flag, and begin slitting throats. -- H. L. Mencken

norton ash wrote:One thing I can say for sure is that watching MTV Cribs is more likely to make me violent (and greedy, and dishonest) than any amount of violent films. MTV Cribs is one of the best arguments for full-scale revolution I've ever seen in my life, and I hope I never have to see a better one.

Yep, but Ahab, have you seen My Super Sweet 16?

norton ash wrote:Every normal man must be tempted at times to spit upon his hands, hoist the black flag, and begin slitting throats. -- H. L. Mencken

AhabsOtherLeg wrote:Anyway, just wanted to re-state that this is the most useful and worthwhile thread on the internet at this moment in time. Keep it up.

.

AhabsOtherLeg wrote:norton ash wrote:One thing I can say for sure is that watching MTV Cribs is more likely to make me violent (and greedy, and dishonest) than any amount of violent films. MTV Cribs is one of the best arguments for full-scale revolution I've ever seen in my life, and I hope I never have to see a better one.

SNIP

This is the wrong thread for this kind of stuff, though, isn't it? Sorry all. The grown ups are talking in here, and it's fascinating. I take my leave.norton ash wrote:Every normal man must be tempted at times to spit upon his hands, hoist the black flag, and begin slitting throats. -- H. L. Mencken

Well, quite. That Mencken knew what he was on about.

Soros, Falcone Defend Hedge Funds at House Hearing

By Katherine Burton and Lorraine Woellert

Nov. 13 (Bloomberg) -- Hedge-fund managers including George Soros and Philip Falcone, in an unprecedented appearance before Congress, defended their practices and profits while splitting over whether the U.S. should impose stricter regulations.

``This is not a case where management takes huge bonuses or stock options while the company is failing,'' said Falcone, one of five billionaire investors who testified today before the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform in Washington.

Falcone, senior managing director of New York-based Harbinger Capital Partners, urged Congress to require more disclosure by hedge funds, which oversee $1.7 trillion of investments. Soros, founder of Soros Fund Management LLC, cautioned against ``ill-considered'' rules because this industry is reeling from market losses and client defections.

``We do not need greater regulation of hedge funds,'' said Kenneth Griffin, founder of Citadel Investment Group LLC in Chicago. ``We've not seen hedge funds as a focal point of the carnage.''

The hearing was called by committee Chairman Henry Waxman, whose panel doesn't have jurisdiction over securities-industry legislation. Even so, his interest suggests the industry faces increased scrutiny and regulation next year after President- elect Barack Obama takes office.

Registration Redux

Senator Chuck Grassley, an Iowa Republican, said he would reintroduce legislation to require hedge funds to register with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. In 2006, the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals overturned an SEC rule requiring registration, saying the agency overstepped its authority.

Soros, Falcone, Griffin were joined by Paulson & Co.'s John Paulson and James Simons, head of Renaissance Technologies LLC, in testifying as part of a congressional investigation into the credit crunch that has pushed major economies to the brink of recession. Selling by hedge funds, many of which are facing client defections, has been a factor in driving financial markets lower.

This year has been the worst on record for hedge funds, with the average fund losing 15.5 percent through October, according to data compiled by Hedge Fund Research Inc. of Chicago. That compared with the 34 percent decline by the Standard & Poor's 500 Index, a benchmark for the biggest U.S. stocks.

Waxman began by questioning the men about whether their industry is a risk to the financial system, an idea they downplayed. The hearing is one of many Democrats are convening to explore the causes of the global financial crisis.

`Unimaginable Success'

Hedge-fund managers have had ``unimaginable success'' and, while being ``virtually unregulated,'' many enjoy special tax breaks, said Waxman, a California Democrat. Today's witnesses, he said, earned on average more than $1 billion last year, profits they were able in many cases to treat as capital gains rather than as ordinary income, which is taxed at a higher rate.

``I gotta tell you, that is a staggering amount of money,'' said Representative Elijah Cummings, a Maryland Democrat. ``You are not taxed like ordinary citizens.''

The investors urged lawmakers not to change tax rules for hedge funds without changing them for all long-term investors.

Falcone said that 98 percent of his income was taxed as ordinary income. He along with Soros and Simons said they would agree to higher taxes on long-term gains.

Paulson and Griffin were more reluctant.

``I believe our tax situation is fair,'' Paulson said. ``If your constituents, whether a plumber or a teacher, bought a stock and if they held that stock for more than a year they would pay a long-term capital gains rate.''

Waxman and Representative Thomas Davis of Virginia, the panel's top Republican, suggested the need for more oversight of the industry.

Main Street Impact

``This isn't just about sophisticated, high-stakes investors anymore,'' Davis said. ``Institutional funds and public pensions now have a huge stake in hedge funds' promises of steady, above-market returns. That means public employees and middle-income senior citizens, not just Tom Wolfe's Masters of the Universe, lose money when hedge funds decline or collapse.''

Falcone, 46, said he supported more public disclosure and transparency. Investors ``have a right to know what assets companies have an interest in -- whether on or off their balance sheets -- and what those assets are really worth,'' he said.

Fed Disclosure

Soros warned the committee against ``going overboard with regulation'' now that ``the bubble has now burst and hedge funds will be decimated. I would guess that the amount of money they manage will shrink by between 50 and 75 percent. It would be a grave mistake to add to the forced liquidation currently dislocating markets by ill-considered or punitive regulations.''

Simons suggested that hedge funds' positions be disclosed to regulators and made available to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, though not made public.

The hedge-fund managers also defended their multimillion- dollar compensation, saying they earned money only when their investors did.

``In our business, one of the most fundamental principles is alignment of our interests with those of our clients,'' said Paulson, who takes 20 percent of any gains. ``All of our funds have a 'high-water mark,' which means that if we lose money for our investors, we have to earn it back before we share in future profits.''

Soros, best known for making $1 billion betting against the British pound, is the chairman of the $19 billion Soros Fund Management in New York. He has called credit-default swaps the next crisis area because the market is unregulated, and he has recommended the creation of an exchange where these contracts could be traded, a move seconded by Griffin.

Falcone Reversal

Paulson, 52, runs a New York-based fund that manages about $36 billion. His Credit Opportunities Fund soared almost sixfold in 2007, primarily on wagers that subprime mortgages would tumble. Paulson's Advantage Plus fund has climbed 29 percent this year through October while many managers are enduring the worst year of their careers.

Falcone also profited from a drop in subprime mortgages last year, when his fund, now about $20 billion, doubled. This year the fund was up 42 percent at the end of June and has since tumbled to a loss of about 13 percent. He told the panel that his father, a utility superintendent, never made more than $14,000 a year, and his mother worked in a local shirt factory.

Simons, 70, runs his $29 billion fund out of East Setauket, New York. The former academic makes money by using computer models to trade. His Medallion Fund, made up of his own money and that of his employees, is up more than 50 percent this year.

Griffin, 40, runs the $16 billion Citadel Investment Group LLC in Chicago, and has faced the toughest year out of the five billionaire managers. His funds dropped 38 percent this year through Nov. 4.

To contact the reporters on this story: Katherine Burton in New York at kburton@bloomberg.net; Lorraine Woellert in Washington at lwoellert@bloomberg.net.

Last Updated: November 13, 2008 16:04 EST

Bush's House of Cards

Dean Baker

August 9, 2004

The latest data on growth suggest that the economy may again be faltering, just when President Bush desperately needs good numbers to make the case for his re-election. As bad as the Bush economic record is, it would be far worse if not for the growth of an unsustainable housing bubble through the three and a half years of the Bush Administration.

The housing market has supported the economy both directly--through construction of new homes and purchases of existing homes--and indirectly, by allowing families to borrow against the increased value of their homes. Housing construction is up more than 17 percent from its level at the end of the recession. Purchases of existing homes hit a record of 6.1 million in 2003, more than 500,000 above the previous record set in 2002. Each home purchase is accompanied by thousands of dollars of closing costs, plus thousands more spent on furniture and remodeling.

The indirect impact of the housing bubble is at least as important. Mortgage debt rose by an incredible $2.3 trillion between 2000 and 2003.

This borrowing has sustained consumption growth in an environment in which firms have been shedding jobs and cutting back hours, and real wage growth has fallen to zero, although the gains from this elixir are starting to fade with a recent rise in mortgage rates and many families are running out of equity to tap.

The red-hot housing market has forced up home prices nationwide by 35 percent after adjusting for inflation. There is no precedent for this sort of increase in home prices. Historically, home prices have moved at roughly the same pace as the overall rate of inflation. While the bubble has not affected every housing market--in large parts of the country home prices have remained pretty much even with inflation--in the bubble areas, primarily on the two coasts, home prices have exceeded the overall rate of inflation by 60 percentage points or more.

The housing enthusiasts, led by Alan Greenspan, insist that the run-up is not a bubble, but rather reflects fundamental factors in the demand for housing. They cite several factors that could explain the price surge: a limited supply of urban land, immigration increasing the demand for housing, environmental restrictions on building, and rising family income leading to increased demand for housing.

A quick examination shows that none of these explanations holds water. Land is always in limited supply; that fact never led to such a widespread run-up in home prices in the past. Immigration didn't just begin in the late nineties. Also, most recent immigrants are low-wage workers. They are not in the market for the $500,000 homes that middle-class families now occupy in bubble-inflated markets. Furthermore, the demographic impact of recent immigration rates pales compared to the impact of baby boomers first forming their first households in the late seventies and eighties. And that did not lead to a comparable boom in home prices.

Environmental restrictions on building, moreover, didn't begin in the late nineties. In fact, in light of the election of the Gingrich Congress in 1994 and subsequent Republican dominance of many state houses, it's unlikely that these restrictions suddenly became more severe at the end of the decade. And the income growth at the end of the nineties, while healthy, was only mediocre compared to the growth seen over the period from 1951 to 1973. In any event, this income growth has petered out in the last two years.

The final blow to the argument of the housing enthusiasts is the recent trend in rents. Rental prices did originally follow sale prices upward, although not nearly as fast. However, in the last two years, the pace of rental price increases has slowed under the pressure of record high vacancy rates. In some bubble areas, like Seattle and San Francisco, rents are actually falling. No one can produce an explanation as to how fundamental factors can lead to a run-up in home sale prices, but not rents.

At the end of the day, housing can be viewed like Internet stocks on the NASDAQ. A run-up in prices eventually attracts more supply. This takes the form of IPOs on the NASDAQ, and new homes in the housing market. Eventually, there are not enough people to sustain demand, and prices plunge.

The crash of the housing market will not be pretty. It is virtually certain to lead to a second dip to the recession. Even worse, millions of families will see the bulk of their savings disappear as homes in some of the bubble areas lose 30 percent, or more, of their value. Foreclosures, which are already at near record highs, will almost certainly soar to new peaks. This has happened before in regional markets that had severe housing bubbles, most notably in Colorado and Texas after the collapse of oil prices in the early eighties. However, this time the bubble markets are more the rule than the exception, infecting most of real estate markets on both coasts, as well as many local markets in the center of the country.

In this context, it's especially disturbing that the Bush administration has announced that it is cutting back Section 8 housing vouchers, which provide rental assistance to low income families, while easing restrictions on mortgage loans. Low-income families will now be able to get subsidized mortgage loans through the Federal Housing Administration that are equal to 103 percent of the purchase price of a home. Home ownership can sometimes be a ticket to the middle class, but buying homes at bubble-inflated prices may saddle hundreds of thousands of poor families with an unmanageable debt burden.

As with the stock bubble, the big question in the housing bubble is when it will burst. No one can give a definitive answer to that one, but Alan Greenspan seems determined to ensure that it will be after November. Instead of warning prospective homebuyers of the risk of buying housing in a bubble-inflated market, Greenspan gave Congressional testimony in the summer of 2002 arguing that there is no such bubble. This is comparable to his issuing a "buy" recommendation for the NASDAQ at the beginning of 1999. More recently, Greenspan has done everything in his power to keep mortgage rates as low as possible, at one point even offering markets the hope that the Fed would take the extraordinary measure of directly buying long-term Treasury bonds. The man who testified that the Bush tax cuts were a good idea apparently has one last job to perform for the President.

Dean Baker is the co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research.

Also by The Author

Solution to Unemployment: Pay People to Work Shorter Hours

There is an easy way to get unemployed workers back to work: pay them to work shorter hours.

The New Road to Serfdom

An illustrated guide to the coming real estate collapse

By Michael Hudson

Originally published in Harper’s, May 2006

Michael Hudson is Distinguished Professor of Economics at the University of Missouri, Kansas City and the author of many books, including "Super Imperialism: The Origin and Fundamentals of U.S. World Dominance."

Nigel Holmes was the graphics director of Time magazine for sixteen years and is the author of Wordless Diagrams.

"Even men who were engaged in organizing debt-serf cultivation and debt-serf industrialism in the American cotton districts, in the old rubber plantations, and in the factories of India, China, and South Italy, appeared as generous supporters of and subscribers to the sacred cause of individual liberty."

- H. G. Wells, The Shape of Things to Come - (1936)

Never before have so many Americans gone so deeply into debt so willingly. Housing prices have swollen to the point that we've taken to calling a mortgage–by far the largest debt most of us will ever incur–an "investment." Sure, the thinking goes, $100,000 borrowed today will cost more than $200,000 to pay back over the next thirty years, but land, which they are not making any more of, will appreciate even faster. In the odd logic of the real estate bubble, debt has come to equal wealth.

And not only wealth but freedom–an even stranger paradox. After all, debt throughout most of history has been little more than a slight variation on slavery. Debtors were medieval peons or Indians bonded to Spanish plantations or the sharecropping children of slaves in the postbellum South. Few Americans today would volunteer for such an arrangement, and therefore would-be lords and barons have been forced to develop more sophisticated enticements.

The solution they found is brilliant, and although it is complex, it can be reduced to a single word–rent. Not the rent that apartment dwellers pay the landlord but economic rent, which is the profit one earns simply by owning something. Economic rent can take the form of licensing fees for the radio spectrum, interest on a savings account, dividends from a stock, or the capital gain from selling a home or vacant lot. The distinguishing characteristic of economic rent is that earning it requires no effort whatsoever. Indeed, the regular rent tenants pay landlords becomes economic rent only after subtracting whatever amount the landlord actually spent to keep the place standing.

Most members of the rentier class are very rich. One might like to join that class. And so our paradox (seemingly) is resolved. With the real estate boom, the great mass of Americans can take on colossal debt today and realize colossal capital gains—and the concomitant rentier life of leisure—tomorrow. If you have the wherewithal to fill out a mortgage application, then you need never work again. What could be more inviting—or, for that matter, more egalitarian?

That’s the pitch, anyway. The reality is that, although home ownership may be a wise choice for many people, this particular real estate bubble has been carefully engineered to lure home buyers into circumstances detrimental to their own best interests. The bait is easy money. The trap is a modern equivalent to peonage, a lifetime spent working to pay off debt on an asset of rapidly dwindling value.

Most everyone involved in the real estate bubble thus far has made at least a few dollars. But that is about to change. The bubble will burst, and when it does, the people who thought they would be living the easy life of a landlord will soon find that what they really signed up for was the hard servitude of debt serfdom.

Mortgages account for most of the net growth in debt since 2000 - billions

1 The new road to serfdom begins with a loan. Since 2003, mortgages have made up more than half of the total bank loans in America—more than $300 billion in 2005 alone. Without that growing demand, banks would have seen almost no net loan growth in recent years.

A $1,000 monthly payment can carry different levels of debt

2 Why is the demand for mortgage debt so high? There are several reasons, but all of them have to do with the fact that banks encourage people to think of mortgage debt in terms of how much they can afford to pay in a given month—how far they can stretch their paychecks—rather than in terms of the total amount of the loan. A given monthly payment can carry radically different amounts of debt, depending on the rate of interest and how long those payments last. The purchasing power of a $1,000 monthly payment, for instance, nearly triples as the debt lingers and the interest rate declines.

3 As it happens, banks are increasingly unhurried about repayment. Nearly half the people buying their first homes last year were allowed to do so with no money down, and many of them took out so-called interest-only loans, for which payment of the actual debt—amortization—was delayed by several years. A few even took on “negative amortization” loans, which dispense entirely with payments on the principal and require only partial payment of the interest itself. (The extra interest owed is simply added to the total debt, which can grow indefinitely.) The Federal Reserve, meanwhile, has been pushing interest rates down for more than two decades.

corporations hide their real estate profits behind depreciation

4 The IRS has helped create demand for debt as well by allowing tax breaks—the well-known home-mortgage deduction, for instance—that can transform a loan into an attractive tax shelter. Indeed, commercial real estate investors hide most of their economic rent in “depreciation” write-offs for their buildings, even as those buildings gain market value. The pretense is that buildings wear out or become obsolete just like any other industrial investment. The reality is that buildings can be depreciated again and again, even as the property’s market value increases.

the tax burden has shifted from property to labor and consumption

5 Local and state governments have done their share too, by shifting the tax burden from property to labor and consumption, in the form of income and sales taxes. Since 1929, the proportion of tax burden has almost completely reversed itself.

real estate prices have far outpaced national income

6 In recent years, though, the biggest incentive to home ownership has not been owning a home per se, or even avoiding taxes, but rather the eternal hope of getting ahead. If the price of a $200,000 house shoots up 15 percent in a given year, the owner will realize a $30,000 capital gain. Many such owners are spending tomorrow’s capital gain today by taking out home-equity loans. For families whose real wages are stagnant or falling, borrowing against higher property prices seems almost like taking money from a bank account that has earned dividends. In a study last year, Alan Greenspan and James Kennedy found that new home-equity loans added $200 billion to the U.S. economy in 2004 alone.

capital gains are taxed at a lower rate than ever - top rate

7 It is also worth noting that capital gains—economic rent “earned” without any actual labor or industrial investment—are increasingly untaxed.

housing prices have far outpaced consumer prices, even as monthly

payments remain affordable

8 All of these factors have combined to lure record numbers of buyers into the real estate market, and home prices are climbing accordingly. The median price of a home has more than doubled in the last decade, from $109,000 in 1995 to a peak of more than $206,000 in 2005. That growth far out-paces the consumer price index, and yet housing affordability—the measure of those month-to-month housing costs—has remained about the same.

mortgage debt is rising as a proportion of gdp

9 That sounds like good news. But those rising prices also mean that more people owe more money to banks than at any other time in history. And that’s not just in terms of dollars—$11.8 trillion in outstanding mortgages—but also as a proportion of the national economy. This debt is now on track to surpass the size of America’s entire gross domestic product by the end of the decade.

the production/consumption economy

10 Even that huge debt might not seem so bad, what with those huge capital gains beckoning from out there in the future. But the boom, alas, cannot last forever. And when the growth ceases, the market will collapse. Understanding why, though, requires a quick detour into economic theory. We often think of “the economy” as no more than a closed loop between producers and consumers. Employers hire workers, the workers create goods and services, the employers pay them, and the workers use that money to buy the goods and services they created.

the keynesian economy

11 As we have seen, though, the government also plays a significant role in the economy. Tax hikes drain cash from the circular flow of payments between producers and consumers, slowing down overheated economies. Deficit spending pumps more income into that flow, helping pull stalled economies out of recession. This is the classical policy model associated with John Maynard Keynes.

the FIRE economy

12 A third actor also influences the nation’s fortune. Economists call it the FIRE sector, short for finance, insurance, and real estate. These industries are so symbiotic that the Commerce Department reports their earnings as a composite. (Banks require mortgage holders to insure their properties even as the banks reach out to absorb insurance companies. Meanwhile, real estate companies are organizing themselves as stock companies in the form of real estate investment trusts, or REITs—which in turn are underwritten by investment bankers.) The main product of these industries is credit. The FIRE sector pumps credit into the economy even as it withdraws interest and other charges.

the miracle of compound interest

13 The FIRE sector has two significant advantages over the production/consumption and government sectors. The first is that interest wealth grows exponentially. That means that as interest compounds over time, the debt doubles and then doubles again. The eighteenth-century philosopher Richard Price identified this miracle of compound interest and observed, somewhat ruefully, that had he been able to go back to the day Jesus was born and save a single penny—at 5 percent interest, compounded annually—he would have earned himself a solid gold sphere 150 million times bigger than Earth.

the rentier economy

14 The FIRE sector’s other advantage is that interest payments can quickly be recycled into more debt. The more interest paid, the more banks lend. And those new loans in turn can further drive up demand for real estate—thereby allowing homeowners to take out even more loans in anticipation of future capital gains. Some call this perpetual-motion machine a “post-industrial economy,” but it might more accurately be called a rentier economy. The dream is that the FIRE sector will expand to embrace the fortune of every American—that we need not work or produce anything, or, for that matter, invest in new technology or infrastructure for the nation. We certainly need not pay taxes. We need only participate in the boom itself. The miracle of compound interest will allow every one of us to be a rentier, feasting on interest, dividends, and capital gains.

rich people are getting a bigger share of overall economic rent

15 In reality, alas, we can’t all be rentiers. Just as, in Voltaire’s phrase, the rich require an abundant supply of the poor, so too does the rentier class require an abundant supply of debtors. There is no other way. In fact, the vast majority of Americans have seen their share of the rental pie decrease over the last two decades, even as the real estate pie as a whole has expanded. Everyone got a little richer, but rich people got much, much richer.

the miracle of compound interest will inevitably confront the s-curve of reality

16 We will be hard-pressed to maintain even this semi-blissful state. Like any living organism, real economies don’t grow exponentially, or even in a straight line. They taper off into an S-curve, the victim of their own successes. When business is good, the demand for labor, raw materials, and credit increases, which leads to large jumps in wages, prices, and interest rates, which in turn act to depress the economy. That is where the miracle of compound interest founders. Although many people did save money at interest two thousand years ago, nobody has yet obtained even a single Earth-volume of gold. The reason is that when a business cycle turns down, debtors cannot pay, and so their debts are wiped out in a wave of bankruptcy along with all the savings invested in these bad loans.

in japan, real estate prices fell as quickly as they rose

17 Japan learned this lesson in the Nineties. As the price of land went up, banks lent more money than people could afford to pay interest on. Eventually, no one could afford to buy any more land, demand fell off, and prices dropped accordingly. But the debt remained in place. People owed billions of yen on homes worth half that—homes they could not sell. Many commercial owners simply went into foreclosure, leaving the banks not only with “non-performing loans” that were in fact dead losses but also with houses no one wanted—or could afford—to buy. And that lack of incoming interest also meant that banks had no more reserves to lend, which furthered the downward spiral. Britain’s similarly debt-burdened economy inspired a dry witticism: “Sorry you lost your job. I hope you made a killing on your house.”

interest rates are on the rise

18 We have already reached our own peak. As of last fall, even Alan Greenspan had detected “signs of froth” in the housing market. Home prices had “risen to unsustainable levels” in some places, he said, and would have exceeded the reach of many Americans long ago if not for “the dramatic increase in the prevalence of interest-only loans” and “other, more exotic forms of adjustable-rate mortgages” that “enable marginally qualified, highly leveraged borrowers to purchase homes at inflated prices.” If the trend continues, homeowners and banks alike “could be exposed to significant losses.” Interest rates, meanwhile, have begun to creep up.

the annual sale of existing homes has more than doubled since 1989 - millions of homes

19 So: America holds record mortgage debt in a declining housing market. Even that at first might seem okay—we can just weather the storm in our nice new houses. And in fact things will be okay for homeowners who bought long ago and have seen the price of their homes double and then double again. But for more recent homebuyers, who bought at the top and who now face decades of payments on houses that soon will be worth less than they paid for them, serious trouble is brewing. And they are not an insignificant bunch.

negative equity traps debtors

20 The problem for recent homebuyers is not just that prices are falling; it’s that prices are falling even as the buyers’ total mortgage remains the same or even increases. Eventually the price of the house will fall below what homeowners owe, a state that economists call negative equity. Homeowners with negative equity are trapped. They can’t sell—the declining market price won’t cover what they owe the bank—but they still have to make those (often growing) monthly payments. Their only “choice” is to cut back spending in other areas or lose the house—and everything they paid for it—in foreclosure.

Free markets are based on choice. But more and more homeowners are discovering that what they got for their money is fewer and fewer choices. A real estate boom that began with the promise of “economic freedom” almost certainly will end with a growing number of workers locked in to a lifetime of debt service that absorbs every spare penny. Indeed, a study by The Conference Board found that the proportion of households with any discretionary income whatsoever had already declined between 1997 and 2002, from 53 percent to 52 percent. Rising interest rates, rising fuel costs, and declining wages will only tighten the squeeze on debtors.

But homeowners are not the only ones who will pay. The overall economy likely will shrink as well. That $200 billion that flowed into the “real” economy in 2004 is already spent, with no future capital gains in the works to fuel more such easy money. Rising debt-service payments will further divert income from new consumer spending. Taken together, these factors will further shrink the “real” economy, drive down those already declining real wages, and push our debt-ridden economy into Japan-style stagnation or worse. Then only the debt itself will remain, a bitter monument to our love of easy freedom.

Chart Sources

1 Federal Reserve; 2 Lendingtree.com mortgage calculator; 3 Freddie Mac; 4,5 Bureau of Economic Analysis; 6 Federal Reserve and Bureau of Economic Analysis; 7 U.S. Treasury Department; 8 Moody’s Economy.com and Bureau of Labor Statistics; 9 Federal Reserve and Bureau of Economic Analysis; 15 Center on Budget and Policy Priorities; 17 Japan Real Estate Institute; 18 Federal Housing Finance Board; 19 National Association of Realtors.

Bill Black Testimony on Lehman Bankruptcy

By: Jane Hamsher Tuesday April 20, 2010 2:28 pm

FDL Contributor Bill Black scorched everyone with his testimony on the failure of Lehman Brothers before the House Financial Services Committee today.

CHAIRMAN KANJORSKI: And now we’ll hear from Mr. William K. Black, Associate Professor of Economics and Law, the University of Missouri, Kansas City School of Law. Mr. Black.

BILL BLACK: Members of the Committee, thank you.

You asked earlier for a stern regulator, you have one now in front of you. And we need to be blunt. You haven’t heard much bluntness in hours of testimony.

We stopped a nonprime crisis before it became a crisis in 1991 by supervisory actions.

We did it so effectively that people forgot that it even existed, even though it caused several hundred million dollars of losses — but none to the taxpayer. We did it by preemptive litigation, and by supervision. We broke a raging epidemic of accounting control fraud without new legislation in the period of 1984 through 1986.

Legislation would’ve been helpful, we sought legislation, but we didn’t get it. And we were able to stop that because we didn’t simply consider business as usual.

Lehman’s failure is a story in large part of fraud. And it is fraud that begins at the absolute latest in 2001, and that is with their subprime and liars’ loan operations.

Lehman was the leading purveyor of liars’ loans in the world. For most of this decade, studies of liars’ loans show incidence of fraud of 90%. Lehmans sold this to the world, with reps and warranties that there were no such frauds. If you want to know why we have a global crisis, in large part it is before you. But it hasn’t been discussed today, amazingly.

Financial institution leaders are not engaged in risk when they engage in liars’ loans — liars’ loans will cause a failure. They lose money. The only way to make money is to deceive others by selling bad paper, and that will eventually lead to liability and failure as well.

When people cheat you cannot as a regulator continue business as usual. They go into a different category and you must act completely differently as a regulator. What we’ve gotten instead are sad excuses.

The SEC: we’re told they’re only 24 people in their comprehensive program. Who decided how many people there would be in their comprehensive program? Who decided the staffing? The SEC did. To say that we only had 24 people is not to create an excuse — it’s to give an admission of criminal negligence. Except it’s not criminal, because you’re a federal employee.

In the context of the FDIC, Secretary Geithner testified today that this pushed the financial system to the brink of collapse But Chairman Bernanke testified we sent two people to be on site at Lehman. We sent fifty credit people to the largest savings and loan in America. It had 30 billion in assets. We had a whole lot less staff than the Fed does.

We forced out the CEO. We replaced the CEO. We did that not through regulation but because of our leverage as creditors. Now I ask you, who had more leverage as creditors in 2008? The Fed, as compared to the Federal Home Loan Bank of San Francisco, 19 years earlier? Incomprehensible greater leverage in the Fed, and it simply was not used.

Let’s start with the repos. We have known since the Enron in 2001 that this is a common scam, in which every major bank that was approached by Enron agreed to help them deceive creditors and investors by doing these kind of transactions.

And so what happened? There was a proposal in 2004 to stop it. And the regulatory heads — there was an interagency effort — killed it. They came out with something pathetic in 2006, and stalled its implication until 2007, but it ’s meaningless.

We have known for decades that these are frauds. We have known for a decade how to stop them. All of the major regulatory agencies were complicit in that statement, in destroying it. We have a self-fulfilling policy of regulatory failure

because of the leadership in this era.

We have the Fed, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, finding that this is three card monty. Well what would you do, as a regulator, if you knew that one of the largest enterprises in the world, when the nation is on the brink of economic collapse, is engaged in fraud, three card monty? Would you continue business as usual?

That’s what was done. Oh they met a lot — they say “we only had a nuclear stick.” Sounds like a pretty good stick to use, if you’re on the brink of collapse of the system. But that’s not what the Fed has to do. The Fed is a central bank. Central banks for centuries have gotten rid of the heads of financial institutions. The Bank of England does it with a luncheon. The board of directors are invited. They don’t say “no.” They are sat down.

The head of the Bank of England says “we have lost confidence in the head of your enterprise. We believe Mr. Jones would be an effective replacement. And by 4 o’clock that day, Mr. Jones is running the place. And he has a mandate to clean up all the problems.

Instead, every day that Lehman remained under its leadership, the exposure of the American people to loss grew by hundreds of millions of dollars on average. Auroroa was pumping out up to 30 billion dollars a month in liars’ loans. Losses on those are running roughly 50% to 85 cents on the dollar. It is critical not to do business as usual, to change.

We’ve also heard from Secretary Geithner and Chairman Bernanke — we couldn’t deal with these lenders because we had no authority over them. The Fed had unique authority since 1994 under HOEPA to regulate all mortgage lenders. It finally used it in 2008.

They could’ve stopped Aurora. They could’ve stopped the subprime unit of Lehman that was really a liar’s loan place as well as time went by.

(Kanjorski bangs the gavel)

Thank you very much.

This year's Department of Economics sponsored lecture, The Steinhardt, features Dr. William Black, University of Missouri-Kansas City. It occurred Thursday, Feb. 18th, 2010, 7:30-9:00 PM, at the Council Chamber. The title of Dr. Black's talk is: Why Elite Frauds Cause Recurrent, Intensifying Economic, Political and Moral Crises.

"From the Greek Tragedy to the Battle of the Bank of England and the U.S. Fed" with French economist, Franck Biancheri. Signs of the coming break-up of Anglo-Saxon financial domination; trends for the second half of 2010; coverage of the Greek problem; the Euro and the Eurozone; bank bailouts; interest rates; money to fund the huge western public debt becoming increasingly difficult to find.

Eurotrash Nations Head Into Default

The US is Not Greece

May 7 - 9, 2010

By MARSHALL AUERBACK

If we learn the wrong lessons from Greece, our social safety net may wind up in tatters.

Many market analysts, commentators and economists claim to be having a hard time finding a metric in which the US is in better financial shape than Greece. Ken Rogoff, for example, recently warned that a Greek default would usher in a series of sovereign defaults, and suggested recently on NPR that the crisis also had implications for the US. The historian Niall Ferguson made a similar claim a few months ago in the Financial Times. The cries of the deficit hawks grow louder: Repent all ye fiscal profligates, before the day of reckoning comes.

Let’s dial down the Biblical hysteria a wee bit while there’s still time for rational debate. The market’s recent response to the intensifying pressures in the euro zone suggests that investors are beginning to differentiate between countries that are sovereign issuers of currency, such as the US or Japan, and non-sovereign issuers, such as Greece or any other nations in the euro zone. The US dollar is rising in value, notwithstanding the federal deficit, while debt distress in the so-called “PIIGS” countries (ie Greece, Portugal, Spain and Ireland, especially Greece,) are intensifying, thereby driving down the euro to fresh 12 month lows against the dollar.

The relative performance of various currencies against the US dollar is highly instructive in this regard. Over the past 3 months, the Australian, New Zealand and Canadian dollars have all registered gains of some 4 per cent against the greenback. The worst performer? Not surprisingly, the euro, down 6.3 per cent over that period. Whether consciously or not, the markets are demonstrating that they understand the distinctions between users of currencies (who face an external funding constraint), and those nations that face no constraint in their deficit spending activities because they are creators of currency.