http://www.democraticunderground.com/di ... 439x358064

Ten Principles for Avoiding National Economic Catastrophe

The ten principles that I discuss in this post come from a book written by Nassim Nicholas Taleb, titled “The Black Swan – The Impact of the Highly Improbable”. The book is not primarily about economics. Rather, it is about how the laws of probability are misunderstood and incorrectly taught in the vast majority of academic institutions regarding highly “improbable” events – as applied to real life circumstances.

I put “improbable” in quotes because, as Taleb correctly points out, “improbable” is in the eye of the beholder, which in turn is highly dependent upon the information that the beholder is aware of. For example, the recent economic Meltdown of 2008 (which represents economic catastrophe for many millions of Americans, including some in my family) was considered to be highly improbable by the vast majority of Americans prior to its occurrence. But as Taleb points out, rational assessment of information that was publicly available with a certain amount of digging would have made the meltdown appear highly probable rather than improbable. Indeed, he predicted it, as did a handful of others. Another example is that most Americans alive today would have believed that circumnavigation around the North Pole would have been impossible in their life time, based upon the fact that it had been impossible for at least the past 125 thousand years. Yet those familiar with the extent and impact of global warming would not have been surprised to hear of the North Pole becoming circumnavigable – as indeed it became in 2008.

Taleb’s book does not espouse a political point of view. Rather, as noted above, it contains his views on assessing the probability of highly “improbable” events. So his ten principles for what he terms a “black-swan-robust” society are apolitically motivated. I will not go into his views on probability in this post. Rather, I will discuss only the two and a half pages near the end of the book that deal with a “black-swan-robust” society, as applied to our recent economic meltdown.

Principle 1 – What is fragile should break early, while it’s still small

Another way of saying this is that we should never allow our institutions to become “too big to fail” – in other words, so big that their failure would create great damage to our society, necessitating that society bails them out in order to avoid severe consequences.

Barry C. Lynn discusses the dangers of private monopolies in his book, “Cornered – The New Monopoly Capitalism and the Economics of Destruction”:

Monopoly is, after all, merely a form of government that one group of human beings imposes on another group of human beings. Its purpose is simple – to enable the first group to transfer wealth and power to themselves. Monopolists use such private governments to organize and disorganize, to grab and smash, to rule and ruin, in ways that serve their interests only…

Lynn notes that this battle has been fought since the first days of our republic, when Jefferson and Madison battled against the soon-to-be defunct Federalist Party on this issue. Lynn continues:

Ever since, the central battle in our political economy has been between those who would use our federal and state governments to establish and protect private monopolies to empower and enrich the few and those who would use our governments to break or harness private monopolies in order to protect the liberties and properties of the many.

More than a century ago, the Progressive movement became the driving force behind anti-trust laws, such as the Sherman Anti-trust Act of 1890 and the Clayton Anti-trust Act of 1914, which limited corporate economic power by requiring fair competition.

But by the Reagan Revolution of the 1980s, Americans had forgotten about the dangers of monopoly, and right wing propaganda convinced most of them that monopoly is not something to be feared. Consequently we got the Telecommunications Act of 1996 and the Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000, which paved the way for successive huge mergers in the telecommunications industry and the financial industry, respectively. Both set the stage, in their own way, for the record breaking income and wealth inequality and the economic meltdown that followed.

The bottom line is this: When an organization becomes “too big” it gains inordinate economic and political power, enabling it to arrange our economic and political system for its own benefit, at the expense of everyone else. Then, when it fails, it expects – correctly – that the rest of us will bail them out with our hard earned money.

Principle 2 – No socialization of losses and privatization of gains

Socialization of losses, as noted above, is a consequence of “too big to fail”. Taleb sums up the situation:

Whatever may need to be bailed out should be nationalized…. We got ourselves into the worst of capitalism and socialism… In the United States in the 2000s, the banks took over the government. This is surreal.

That is exactly what our government did. Several of our best economists warned about Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner’s plan for continuing President Bush’s bailout. This is what Nobel Prize winning economist Joseph Stiglitz had to say about it:

The U.S. government plan to rid banks of toxic assets will rob American taxpayers by exposing them to too much risk and is unlikely to work… The U.S. government is basically using the taxpayer to guarantee against downside risk on the value of these assets, while giving the upside, or potential profits, to private investors… Quite frankly, this amounts to robbery of the American people. I don't think it's going to work…

Worse yet, the taxpayer bailout of Wall Street was not even accompanied by a plan to enact significant financial reforms in return for the bailout. Taleb recommends nationalization of failed corporations that are “too big to fail”, rather than simple bailouts. Otherwise the irresponsible are rewarded for their failures, as the losses incurred by their irresponsible behaviors are socialized – i.e. transmitted to ordinary Americans who are much less able to pay for them than are the financial elites. Robert Reich commented on how the Wall Street “reform” legislation of 2010 utterly failed to address the basic perversions of our financial system, especially with regard to the issue of pawning off the losses of big banks onto the American people:

The American people will continue to have to foot the bill for the mistakes of Wall Street’s biggest banks because the legislation does nothing to diminish the economic and political power of these giants. It does not cap their size. It does not resurrect the Glass-Steagall Act that once separated commercial (normal) banking from investment (casino) banking. It does not even link the pay of their traders and top executives to long-term performance. In other words, it does nothing to change their basic structure. And for this reason, it gives them an implicit federal insurance policy against failure unavailable to smaller banks – thereby adding to their economic and political power in the future.

Principle 3 – People who were driving a school bus blindfolded (and crashed it) should never be given a new one

This is just another way of saying that those who harm society should be punished rather than rewarded by given another chance to wreak damage on us. Indeed, our system works in that manner with regard to ordinary Americans. But the wealthy and well-connected usually get a free pass when they harm us, no matter how massively.

Former Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin provides an excellent example of how this principle is ignored with respect to wealthy and powerful people. As U.S. Treasury Secretary, Rubin pushed hard for the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act, and the Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000, both which did terrible harm to our economy and contributed greatly to our economic meltdown.

Yet despite this, the next elected Democratic president chose Rubin and men like him, including his protégé Larry Summers, to rely on for economic advice. Robert Kuttner discusses this issue in his book, “A Presidency in Peril – The Inside Story of Obama’s Promise, Wall Street’s Power, and the Struggle to Control our Economic Future”:

Given the abject failure of the financial deregulation that Rubin championed as Clinton’s top economic adviser, followed by the collapse of the business model that he promoted as senior executive at Citigroup, it is remarkable that a consummate outsider like Barack Obama did not view Rubin (or his protégé Summers) as fatally damaged goods. On the contrary, Obama felt he needed men like Rubin and Summers for tutelage, access, and validation. That itself speaks volumes about where power reposes in America…

Glass-Steagall was designed to prevent the kinds of speculative conflicts of interest that pervaded Wall Street in the 1920s and helped bring about the Great Depression (and that reappeared in the 1990s and helped cause the crash of 2007). The Clinton’ administration’s prime architect of the Glass-Steagall repeal was Robert Rubin….

Principle 4 – Don’t let someone making an “incentive” bonus manage a nuclear plant – or your financial risks

This principle speaks to the fact that today’s financial elites are rewarded with multi-million dollar “incentive” bonuses on the basis of short-term results. Consequently, many chose to pursue strategies that were likely to result in reasonably large profits in the short-term but which were highly vulnerable to economic catastrophe. No matter. They get their huge bonuses, and when their organization collapses many thousands of ordinary Americans lose their fortunes, while the top executives get to keep their multi-million dollar bonus. This is what happened when Robert Rubin, as the number two man at Citigroup, ran the organization into the ground while making $15 million a year. Robert Scheer describes this fiasco in his book, “The Great American Stickup – How Reagan Republicans and Clinton Democrats Enriched Wall Street While Mugging Main Street”:

Citigroup, under Saint Rubin’s leadership, was rushing to the cliff like a lemming, pouring resources into markets that were about to collapse… Huge losses from these mortgage securities would soon trigger a dizzying fall for “the nation’s largest and mightiest financial institution”, with Citigroup’s stock value plunging more than 90% in just two years… Those charged with overseeing deals (and regulating pay structures) were so hungry to make short term profits, they neglected to manage their colleagues who were making bad deals…

Principle 5 – Compensate complexity with simplicity

Complex systems are systems in which the failure of one part of the system is likely to lead to a failure of other parts. Furthermore, complex systems can be so difficult to understand that nobody can predict their consequences.

Robert Kuttner explains how India escaped the financial crisis experienced by so much of the rest of the world, as explained to him by Dr. Yaga Reddy, the former governor of the Bank of India, a post equivalent to that of Chairmen of the Federal Reserve in the US:

India somehow missed the consequences of the toxic products invented and exported by US financial institutions. It had no financial crisis… I asked Dr. Reddy how India managed to dodge the financial bullet. “We don’t understand these complex instruments,” he told me with a smile, “so we don’t permit them. We leave them to the advanced nations like you.”…

My reporting has confirmed that Dr. Reddy stood firm in the face of intense pressure from the governments of Britain and the United States, as well as the world’s large banks and their Indian affiliates. He was attacked as old-fashioned and rigid. The Indian central bank under his leadership persisted… to make it unprofitable for Indian banks to create and gamble in the kind of exotic derivative securities that crashed the American system… and Dr. Reddy’s banking colleagues belatedly thanked him.

Principle 6: Do not give children dynamite sticks even if they come with a warning label

Taleb explains the reasoning behind this principle. Actually, it’s kind of a follow-up principle to principle # 5:

Complex financial products need to be banned because nobody understands them, and few are rational enough to know it. We need to protect citizens from themselves, from bankers selling them “hedging” products, and gullible regulators who listen to economic theorists.

Principle 7: Only Ponzi schemes should depend on confidence. Governments should never need to “restore confidence”

Ponzi schemes, such as the one cooked up by Bernard Madoff, succeed only as long as more suckers can be found to buy into them. Such a process cannot last for the long-term because eventually you will run out of suckers. A large and legitimate system, on the other hand, such as the economic system of a superpower nation, should not have to depend upon “restoring confidence”. Matt Taibbi, in his book, “Griftopia – Bubble Machines, Vampire Squids, and the Long Con that Is Breaking America”, explains how former Chairman of the Federal Reserve, Alan Greenspan, completely missed this obvious point. In a chapter titled “The Biggest Asshole in the Universe”, Taibbi explains numerous instances of Greenspan attempting to “instill confidence” into the system:

In July 1990, at the start of the recession that would ultimately destroy the presidency of George H. W. Bush, Greenspan opined: “in the very near term there’s little evidence that I can see to suggest the economy is tilting over (into recession)”… By October, with the U.S. in the sixth of what would ultimately be ten consecutive months of job losses, Greenspan remained stubborn. “The economy”, he said, “has not yet slipped into recession.”… Before the S&L crisis exploded Greenspan could be seen giving a breezy thumbs-up to now-notorious swindler Charles Keating… The mistake he made in 1994 was even worse…. Greenspan told Congress that the risks involved with derivatives were “negligible”, testimony that left the derivatives market unregulated.

Taibbi explains the inappropriateness of “restoring confidence” in such a manner:

If the national economy is a casino and the financial services industry is turning one market after another into a Ponzi scheme, then frantically pumping new money into such a destructive system is madness, no different from lending money to wild-eyed gambling addicts… and that’s exactly what Alan Greenspan did, over and over again.

Finally, Taibbi explains Greenspan’s excuse for his many overly optimistic pronouncements and his failure to address our growing crisis in a constructive manner:

Because we at the Federal Reserve were concerned about sharp reactions in the markets that had grown accustomed to an unsustainable combination of high returns and low volatility, we chose a cautious approach… We recognized… that a shift could impart uncertainty to markets, and many of us were concerned that a large immediate move in rates could create too big a dose of uncertainty, which could destabilize the financial system.

In other words, Greenspan didn’t want to create uncertainty about the Ponzi schemes created by our financial industry.

Principle 8 – Do not give an addict more drugs if he has withdrawal pains

I’m not sure exactly what Taleb is trying to say with this one. Maybe he’s saying that if you have a bad system, you need to change the system rather than continuing to feed it. If the system is destroying people’s lives, and all we do to address that is to bail out those who caused the problem, while neglecting to make substantial changes in the system that got us into trouble, then we shouldn’t expect the results to be any better in the future. As I noted above in discussing principle # 2, in quoting Robert Reich, we bailed out the bad guys while failing to substantially change the system, and even continuing to leave the bad guys in charge of the system. That’s insane.

Principle 9 – Citizens should not depend on financial assets as a repository of value and should not rely on fallible “expert” advice for their retirement

Here is what Taleb has to say about this:

Economic life should be definancialized… Citizens should experience anxiety from their own businesses (which they control), not from their investments (which they do not control).

What Taleb is saying here is that we should not have to depend on a maze of complex financial instruments, which few if any people can understand, and which are invented by people whose main interest is to make a profit rather than to help us to ensure a comfortable retirement. As noted in my discussion of principle # 5, our economic system need not be extraordinarily complex, and in fact a major reason for our current economic tragedy is that many millions of people put their trust in a system that was so complex that nobody understood it.

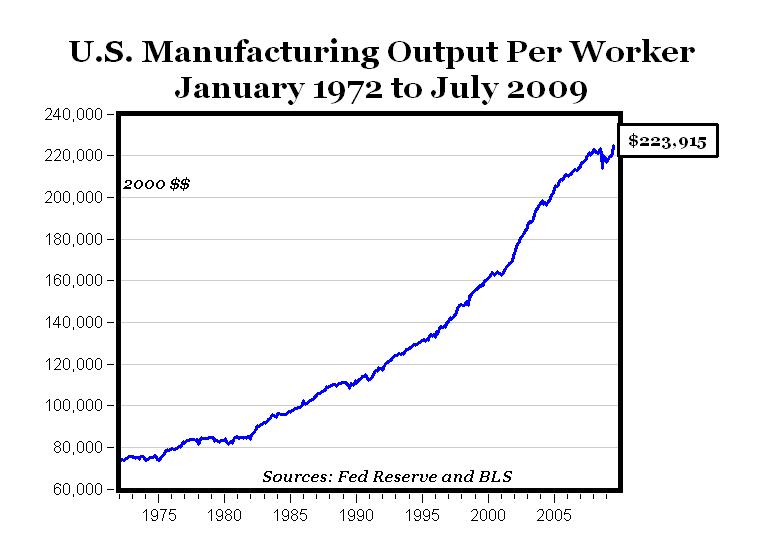

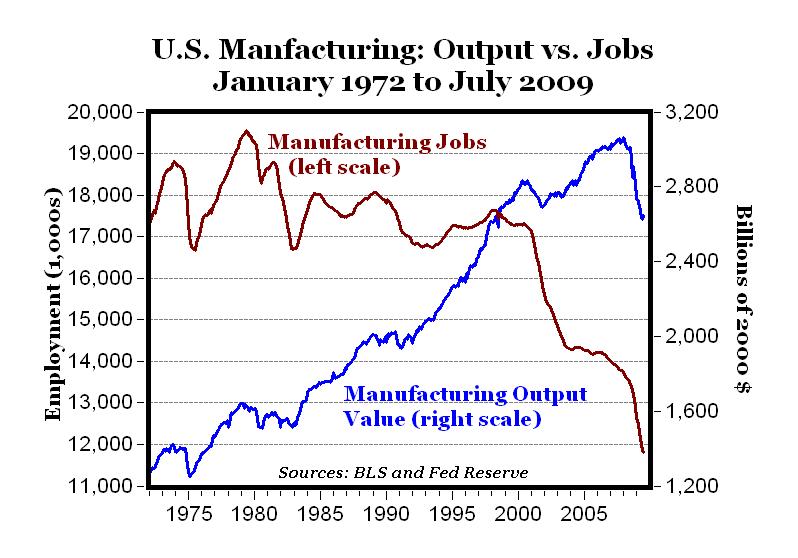

In his book “Rulers and Ruled in the US Empire”, James Petras discusses what happens when we put too much trust in “expert” elite financiers, resulting in a substantial disconnect between rising productivity of the American worker and our economic health:

Within the ruling class, the financial elite is the most parasitical component… One measure of the enormous influence of the financial ruling class in heightening the exploitation of labor is found in the enormous disparity between productivity and wages. Between 2000 and 2005, the US economy grew 12 percent, and productivity (measured by output per hour worked) rose 17 percent while hourly wages rose only 3 percent. Real family income fell during the same period… Three quarters of Americans say they are either worse off or no better off than they were six years ago…. The growth of vast inequalities between the yearly payment of the financial ruling class and the medium salary of workers has reached unprecedented levels….

Principle 10 – Make an omelet with the broken eggs

What Taleb is saying here is that we should not worry about our current system failing. It is rotten to the core, and therefore is beyond repair. We must allow it to fail, and then use the pieces to put together a new system:

The crisis of 2008 was not a problem to fix with makeshift repairs any more than a boat with a rotten hull can be fixed with ad hoc patches. We need to rebuild the new hull with stronger material; we will have to remake the system before it does so itself. Let us move voluntarily into a robust economy by helping what needs to be broken break on its own… banning leveraged buyouts, putting bankers where they belong, clawing back the bonuses of those who got us here (by claiming restitution of the funds paid to, say, Robert Rubin or banksters whose wealth has been subsidized by taxpaying schoolteachers)… Then we will see… smaller firms, a richer ecology, no speculative leverage… a world in which entrepreneurs, not bankers, take risks…

A final word on Taleb’s principles for avoiding national economic catastrophe

Though I don’t understand all of the philosophy on probability that Taleb espouses in his book, I believe that his principles that I discussed above are right on target. I do have one substantial beef with his ideas, however: He seems to say for the most part that failure to follow those principles is a matter of an error in thinking.

I don’t believe that most of this represents error. Rather, I believe that that it represents a purposeful attempt by the elites of our country to become wealthier at the expense of almost everyone else. The financial elites make reckless gambles with our money, not because they’re stupid but because they know full well that if they win they win big, whereas if they lose they still win, because we will bail them out. Their gains are privatized while their losses are socialized, not because such a system makes any sense, but because they have enough money to exert substantial control over a critical mass of our elected officials. They are not made accountable for the vast majority of their failures, simply because they have enough money, connections and power to avoid being made accountable. CEOs make multi-million dollar bonuses not because they deserve it, but simply because they have helped to design a system in which they can. They make huge short-term profits at the expense of the long-term health of their companies, not because they’re stupid, but because they personally profit from doing so. Their financial instruments are unnecessarily complex not because they need to be, but because the complexity enables them to elicit billions of dollars from suckers who are not capable of understanding those instruments or their harmful consequences. I believe that Alan Greenspan deceived the American people numerous times on the state of our economy, not to save our economy, but because that’s what Wall Street wanted him to do, and he knew his bread was buttered by Wall Street. And finally, our system has not been fixed despite overwhelming evidence that it needs to be fixed, not because those in charge of it are concerned about the welfare of ordinary Americans, but simply because they know that leaving the system as it is enables them to continue to enrich themselves.

Taleb probably knows all this, but in the interest of keeping his book apolitical he refrains from emphasizing these things – though his true feelings pop up at times through such means as his not infrequent use of the word “banksters”.

James Galbraith comments on this situation in great detail in his book, “The Predator State”, in which he describes how our country became a “predator state”:

In the late 1970s and 1980s… business leadership saw the possibility of… complete control of the apparatus of the state. In particular, reactionary business leadership, in those sectors most affected by public regulation, saw this possibility and directed their lobbies – the K Street corridor – toward this goal. The Republican Party… became the instrument of this form of corporate control… And to this group was added… those who saw the economic activities of government not in ideological terms but merely as opportunities for private profit on a continental scale… This is the predator state. It is a coalition of relentless opponents of the regulatory framework on which public purpose depends, with enterprises whose major lines of business compete with or encroach on the principal public functions of the enduring New Deal. It is a coalition, in other words, that seeks to control the state partly in order to prevent the assertion of public purpose…

.