This piece is clearly influenced by Autonomous/Workerist perspectives, which in my view are strong in certain ways but weaker in regards to the ways which we might collectively organize to create the fundamental changes which are needed:

http://libcom.org/library/work-free-soc ... federationWork and the free society - Anarchist Federation

The Anarchist Federation analyse work in modern capitalist society, what is wrong with it and what we can all do to help rectify it.

In the film

Fight Club, its central character, Tyler Durden, has a message for those who think they run society and that we exist to meet their needs:

"The people you're after are everyone you depend on. We do your laundry, cook your food and serve you dinner. We guard you while you sleep. We drive your ambulances. DO NOT FUCK WITH US!"

"It has become an article of the creed of modern morality that all labour is good in itself; a convenient belief to those who live on the wealth of others." -- William Morris,

Useful Work vs Useless Toil 1885

Let’s face it, work as we know and loathe it today, sucks. Anybody who has worked for a wage or a salary will confirm that. Work, for the vast majority of us, is forced labour. And it feels like it too! Whether you’re working on a casual or temporary basis and suffer all the insecurity that involves or are ‘lucky’ enough to have a permanent position where job security tightens like a noose around your neck, it’s pretty much the same. Work offers it all: physical and nervous exhaustion, illness and, more often than not, mind-numbing boredom. You can add the feeling of being shafted for the benefit of someone else’s profit to the list.

Work eats up our lives. It dominates every aspect of our existence. When we’re not at the job we’re travelling to or from it, preparing or recovering from it, trying to forget about it or attempting to escape from it in what is laughably called our ‘leisure’ time. Work is a truly offensive four-letter word too horrifying to contemplate. We sacrifice the best part of our waking lives to work in order to survive in order to work. It’s a kind of drug, numbing us, clouding our minds with the wage packet and all the ‘benefits’ of consumerism it brings. Apart from the basic fact that if you don’t work and would rather not accept the pittance of state benefits you don’t eat, wage slaves are dragooned into ‘gainful employment’ by ideologies designed to persuade us of the personal and social necessity of ‘having a job’.

Of course there is resistance to work, refusal to work, revolts against work, if largely unreported. It is an interesting fact that in 2002 in Britain, there were 33m working days lost to stress, 60 times more than the 550,000 lost to strikes. That is more than the number of days work lost to industrial action in the supposedly dark days of the late 1970s, a period of ‘industrial chaos’ that led to Thatcher’s rise. A generation of political battle, legislation and public policy to destroy the trade union movement and suppress industrial conflict has been spectacularly subverted. Well, what did they expect?

ANCIENT IDEAS ALIVE TODAY

"If work were so pleasant, the rich would keep it for themselves" - Mark Twain

The western model of civilisation is riddled with the idea that progress derives from a privileged and leisured class supported by a toiling, managed and controlled under-class. Ancient Greek civilization, the model for modern democracies, depended entirely on a captive population of helots, or slaves, to maintain its aristocrats, thinkers, poets, artists and soldiers in luxury and leisure. Across the ancient world, slavery and many forms of bonded labour were the ‘norm’ and many of the so-called great civilisations were built on the toil and misery of millions of powerless and despised workers.

An identifiable ideology of work began to take shape with the decline of slavery and the emergence of feudalism. Many medieval peasant uprisings and heretical movements proclaimed the poverty of Christ and tried to reclaim the ‘common bounty’ of the earth from the priests and nobles who had stolen it. They proclaimed earthly utopias where the power of church and nobility to enforce work through taxation would be ended by sharing out the wealth of both amongst the poor. This new ideology of equality and equity was deeply threatening to both Church and State. In response, the idea of work as a divinely ordained and spiritual activity began to be preached from the pulpits. Those who worked gained a new status in a divine hierarchy that had nobles and priests at the top, sturdy yeomen in the middle, peasant below. The free spirits who resisted domestication, ‘the sturdy beggars’ of our history books, were vilified and persecuted by draconian laws against vagrancy and vagabondage. Individuals who had not been integrated into the economy were portrayed as lazy and ungodly outlaws and forced into what would eventually become the embryonic working class.

The ideas of the Reformation contained within them the source of our current problem. Work was divinely ordained but the reward of work, wealth and status, would set us free to perform God’s good works. Members of the ‘new’ religions, like Calvinism, dedicated themselves to working hard and accumulating wealth, mute witness to the favour God had bestowed upon them. This single-minded, methodical and disciplined ideology was highly useful to the emerging capitalist classes who were, in many countries, the religious classes as well. It also provided a theory of society that persuaded people that it was better to be ‘free’ (by which they meant a wage slave at the mercy of the master who needs labour) than the benighted serf of medieval times. As a result capitalism fundamentally changed the nature of work.

SURPLUS VALUE AND THE CREATION OF TYRANNY

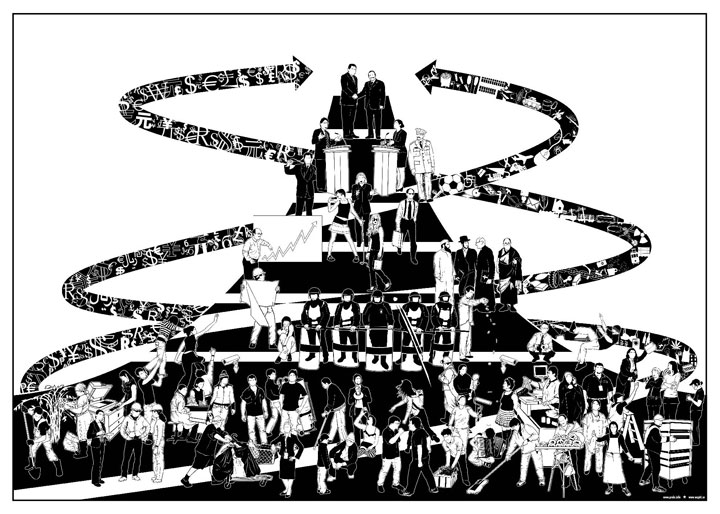

The universal conversion of life into labour is the capitalist means of dominationFor two hundred years industrial capitalism consolidated its grip on society (though not without considerable and violent working class resistance). It’s almost impossible now to realize that virtually everything produced by society (except those requiring collective effort like mining, brewing or baking) was owned by those who produced it, who were able to control the value of their labour through the price they were prepared to sell it for. The ‘success’ of the factory system meant that capitalism had a means to create vast numbers of jobs but at the price of workers surrendering this power and with it, freedom itself.

New laws were passed which restricted the ability of people to work on a temporary or casual basis. Existence without means of visible support became a crime as the industrial masters sought to discipline free peasants and artisans into docile factory armies. To the stick of social stigma, the workhouse and prison for those who refused to work, the bosses added the carrot of permanent employment for the loyal and humble worker, wage differentials for skilled and semi-skilled labour, a mythic social prestige for the ‘kings of labour’ (miners, steelworkers and the like). The ‘job for life’ became our dream and was offered in periods of healthy capitalism then withheld when recession or the need to restructure capitalism arrived. Wage labour became ‘normal’. Unemployment became a moral not social problem and those without work weren’t lucky but ‘victims’, poor unfortunates who deserved to be ‘helped’. This ideology persists despite the best efforts of people like ourselves to get across the basic fact that unemployment is created by capitalism and no-one else. Large numbers of people continue to blame themselves for their unemployed state, for their poverty and lack of any human worth, an attitude the state sees no reason to change.

The work ethic was further reinforced by encouraging workers to identify themselves with their work. Miners' villages, working men’s clubs, factory leagues, trades unions, the occupational pension; they were all a kind of tribal loyalty to ourselves and our master that divided workers from each other as much as it united them. This tribalism was reinforced by craft and trade unionism that encouraged skilled workers to regard themselves as a special case and to practice mutual aid and solidarity only within their own trade.

This deliberate attempt to create a homogeneous working class whose (apparent) self-interest was deeply entwined with that of the ruling class, through certain institutions like social democratic governments, the church and trade unions, reached a peak in corporatist states like Franco’s Spain and Peron’s Argentina in the 1950s-1970s. But towards the end of this period it went into reverse. Capitalism needed to increase demand for its products following the massive contraction of credit (which funds most purchasing in the West) in the 1970s due to the oil-related hyper-inflation and credit squeeze. It did so by using the relative weakness of the working class at the time and the opening of factories in low-wage countries to massively expand the range of goods available. At the same time it promoted the idea of the consumer as an individual, somebody whose identity, status and sense of self-worth was determined by the things that they bought and displayed, whether on the body, the road or in the home.

This process, which has created an apparently fixated, mass consumption society defined primarily not by demographics but by patterns of consumption also destroyed the homogeneity, identity and solidarity of the working class. Of course, this process was not started everywhere at the same time. May corporatist states such as Japan, South Korea and Malaysia still exist though some of their ruling elites complain about the increasing fragmentation of society and alienation of the citizen from anything other than consumption. At the same time, the commodification of society has not spread throughout every society and sometimes does not reach into every community. There are still many places where people may wear the no-longer fashionable tee-shirt or locally-produced fake trainers and still riot when the ruling class turn the screws too tight! But capitalism continues to try and spread its message about the personal value of work and consumption to the individual, rather than to society or within a social context, stealthily undermining the ideas and power of community and mutuality.

Work in its present state is, then, an entirely artificial condition. It is not freely chosen, is not a universal and integrated part of family and society, provides neither intellectual nor spiritual fulfilment for most people and is extremely harmful to mind, body and spirit. Everything that was a good about work the sense of vocation, personal choice, creativity, fulfilment, the sense of value of the individual-in-society has been destroyed for all but a relative handful of artists, craft workers and a few of the ‘professions’. For the rest of us it has become meaningless drudgery from which only death releases us. It is a prison without cages (except for those being worked by the prison-industrial complex) whose governors are the ruling class and whose warders are the bosses, teachers, social workers, employment agencies, police and judicial systems.

WHY WORK TODAY IS A TERRIBLE ORDEAL“The tragedy is that those who work, work so much they are no longer human. Those who don't work are reduced to a miserable existence amidst the spectacle of plenty”.

How old are you when you first realise that having to work for a living is crap? Maybe you’ve always known that work as described by parents, teachers or politicians was not for you. Perhaps the utter futility and meaninglessness of work, in personal terms, has come crashing into your life, or crept up on you year by miserable year. Whichever and however you’ve got to here, you’re now, perhaps, aware that most people hate work and spend their lives in a constant struggle against its imposition. They battle to get beyond and out of being ‘only’ working class. They may succeed, but at what cost?

INDUSTRIALISATION AND MECHANISATIONIn an earlier period, when capitalism was not securely established, workers battled against it in the hope of avoiding it altogether. Very largely they did this by smashing machines and threatening their owners [others attempted to create model communities sometimes it was the same people]. Today the word ‘Luddite’ - used to describe these people - has become an insult, a way of avoiding raising the question of work at all. It just shows how much we have lost control over our own history. When it became clear that capitalism could not be avoided, then our struggle became one of trying to minimise its impact on our lives. The ‘standard’ eight-hour day, the weekend off, premium payments for night and working anti-social hours were all a product of these struggles. If capitalism is so endlessly productive and beneficial, why have these ‘rights’ largely disappeared, been reclaimed by capital? Is it because capitalism can only make profit by driving down the cost of labour or exporting jobs to places where labour costs a few pence per day? Industrialisation and mechanisation was not introduced simply to increase production and profit, spreading this bounty to the four corners of the world. It was introduced deliberately to control and discipline workers (to the needs of the machine, the rhythms of production). New technology does not liberate workers, it cages them, reducing their power to resist the demands of capitalism and is always a response to the struggle of workers either to free themselves from the power of the bosses or to seize a greater share of the wealth they themselves create. What drives industrialisation is not progress or profit-making but the need to dominate and control a fiercely resisting working class and discipline them to the acceptance and necessity of work.

TAYLORISM AND FORDISMThis process began with the very first machines and factories built during the Industrial Revolution. It provoked a hundred years of struggle against the factory and against the fact that workers could no longer say when and where they would work, the factory master did. This resistance was never defeated and, in fact, intensified right up to the start of the Great War. This was the period when the industrial working class challenged capitalism most strongly, the age of the mass strike and working class insurrections against both state and capital.

Capital’s response, once it conceded that it could no longer absolutely exploit our living time, was to bring in technology so that the time it could get from us could be used more effectively. The scientific approach to analysing work and maximising productivity by controlling it was called ‘Taylorism’ and was one of the main shackles placed on workers (along with factory work, employment contracts and the conveyor belt). But Taylorism merely aroused fierce antagonism and resistance within the industrial working class, especially the powerful craft unions. In order to bypass these powerful obstacles to profit-making, new technology was introduced to increase the productivity of workers and replace craft working.

The greatest exponent of this trend was Henry Ford, who dramatically demonstrated the concept of relative surplus value by doing what at the time the early 20th Century was considered impossible. He paid workers 4 or 5 times the ‘going rate’ (actually the bare minimum that could be screwed from the bosses), yet still made a huge profit. By vastly increasing the production of relative surplus value through the use of the assembly line, coupled with FW Taylor’s ‘scientific management’ of the work process, he was able to vastly improve the productivity of his plants. This was a true [capitalist] revolution and its effects are still with us today.

This story is fairly well known. Less well known is what Ford and his like also brought into existence, and that was the worker of the assembly lines, sometimes known as the ‘mass worker’. Whereas before the capitalist had relied largely on skilled workers to manage the production process and in some countries and industries this is still the case the mass worker was a new type. During the development of the working class, it discovered the secret of the production of relative surplus value and learned to exploit this knowledge in its struggle for a fairer share of the product of the national economies of the industrialised world. This in part explains the powerful workerist movements of the 1940s-1980s.

At first capitalist states attempted to contain and demobilise working class resistance by granting it a greater share of the social product, running up big budget deficits in the process. In the UK we had prices and incomes policies and at plant level many non-existent productivity deals were negotiated. But this economic response to a new social reality failed to contain the working class. In Western Europe, the most frightening aspect of the long campaigns against Fordism during this period was not the ever-increasing wage demands which could, after all be accommodated within capitalism but the rejection in many places of the system of ‘factory discipline’ itself; though occupations, strikes, sabotage, marches and riot. In France, Italy, US and the UK in the late 1960s and early 1970s we saw a period of more or less open class struggle. Always at the centre of these struggles was this new ‘mass’ worker. All attempts to contain this mass worker who had discovered that the Fordist system could be destroyed by collective action - failed. ‘Scientific management’ was no answer to workers who collectively could impose their will on the productive process. In Britain the attempt to buy off the workers ended with the intervention of the IMF in 1976, severe recession, the period of defensive struggle from 1978-1983 and the long-term demobilisation of the working class following the Miners Strike of 1984-85. Monetarist policies of the 1980s were re-introduced as within each nation state attempts were made to limit the share of the social product going to labour.

Capital never solved this problem instead it attempted to avoid it altogether by moving to a new stage. First austerity policies were deliberately introduced to break the ‘cycle’ of wage demands, inflation and more wage demands. This brought about the biggest unemployment level since the 1930s. With the mass worker now relatively subdued but still looking to the unions who were an integral part of the imposition of the austerity measures, the stage was set for a more long-term strategy. Capital became more mobile that is it ran away from an insurgent industrial working class to exploit a global proletariat globally. This necessitated changes in technology, especially communications technology that was needed to monitor and control a productive process that was now geographically disparate. But crucially it also needed an ideological offensive to sell the new form of work to a new working class.

The result of this has been the intensification and lengthening of the working week. The value we get for the work we do, which is itself a measure of the value capital can extract from us by way of investment, has decreased steadily over the last twenty years of so. The long campaigns of workers to reduce the working week have been halted and reversed. Where capital has never conceded shorter hours to workers for instance in the fast-industrialising Majority World workers are often at their machine for 60-80 hours a week. This accounts for the fact that though wages are absolutely higher than they were yesterday, most people actually are or feel much poorer than before.

‘Work’ is now something we do throughout our lives. We are no longer ever away from it mobile phones and mobile computers bring ‘work’ to us when we are at leisure, socialising even when we are sleeping. Workers are now on ‘permanent call. Even the unemployed are now engaged in the ‘work’ of ‘looking for work’. And there is an even greater contradiction. Even as the productive capacity of the economy has exploded hugely so that in the 1980s it was seriously suggested by some unions that our problem in the 21st century would be filling the ‘leisure time’ that the new automated economy would bring, at the same time ‘work’ has become even more imposed on gre

ater numbers and most ‘work’ is now devoid of any genuine content at all.

WORK TODAY AND FOR THE REST OF YOUR LIFE“The right to work is the right to misery and denies the possibility of the right not to work”What is work? Is the purpose of work to create spiritual and material abundance as the bosses would have us believe, an abundance we all share in according to the contribution we make? Is the purpose of work, through the artificial and mistaken idea of Progress, to end the need for work in favour of leisure for all? Why are such questions important to anarchists? For anarchists, the imposition of work the socially-created need and compulsion to work is a prison we are desperately seeking to escape. We’re not afraid of work but seek to work freely, doing the things that want and need to be done by our own choice and in our own way or, as William Morris famously said, useful work, not useless toil.

INTENSIFICATION AND INSECURITY“The mass of men live lives of quiet desperation”During the 19th Century, workers struggled to defend their right to determine how and when they would work. This was the great age of co-operatives, strikes and political movements led by small artisans defending individual methods of working against the factory system, of Proudhon’s revelation that Property (by which he meant property above the means to sustain a productive life) was theft. Increasingly trapped within the formal economy of jobs and factories as the 20th Century progressed, workers without the independent means to live struggled to control the amount of labour they would have to give to the system in order to live. This was the age of the struggle for the eight-hour day, for weekends off, holiday and sickness pay, of a decent wage and guaranteed employment.

The defeat of these struggles, and their containment within capitalism thanks to liberal and union interventions on behalf of the bosses, has reduced the ability of the working class to resist the intensification and casualisation of work, while increasing our dependence on the bosses to obtain the means to live. For some, working time has increased beyond the eight-hour shift into overtime and additional part-time work. In many industries such long hours are compulsory. An employee cannot refuse to do overtime work. In low wage industries workers get overtime work as a favour from managements and union leaders. Companies evade laws requiring premium pay for overtime by calling it 'overstay' or offering ‘hardship allowances' instead of overtime pay. Additionally there has been a huge switch from long-term employment with its often-better pay and conditions to sub-contracting and self-employment (although in many cases the newly self-employed entrepreneur still works for just one company; Network Rail is a case in point). The pressure of competitiveness, which compels bosses to confront workers, has been off-loaded onto the small business sector where weaker regulation allows greater and easier exploitation. Let’s look at an example of how intensification is introduced into the workplace.

In 1974 at the Eicher factory in Faridabad 450 workers produced 80 tractors per month. Supervisors then drove workers to make 150 tractors in a month. An incentive scheme was introduced in 1978 and workers started producing 500 tractors a month, then 1000 in 1982 and 1500 per month in 1988. In 1989 a re-engineering plan was implemented. The number of workers was halved, though they still had to produce the same number of tractors, and the incentive scheme was discarded. Eicher then used the latest “human resource development” scheme to reduce the number of workers further and goaded them to produce 2000 tractors monthly. At some time incentives were given when a tractor was assembled in 15 minutes. Now it is done in 10 minutes without incentives, and the management wants it done in seven. The unions in the factory have fought the worker’s cause and fought it well: their members are allowed to take all of nine minutes, not seven, to assemble a tractor. Among industrial wage-workers, then, incentives for increased production are often used to make workers supervise intensification of their own bodies. Incentives are meant to lure workers to give more than normal production. The increased levels of production become the new norm - to be met without incentives. Management then begins a new cycle of increasing work-load and intensity.

A major study from 1999 reported that “the root cause of job insecurity and work intensification lies with the reduced staffing levels pursued by senior managers in response to market pressures from competitors and dominant stakeholders” capitalists, in other words. That same study revealed that 60% of employees in Britain claimed the pace of work and the effort required to do it had greatly increased, resulting in poor general health in the workforce and tense family relationships. Stress and ill-health are made worse by job insecurity. Of course the two are used together to exploit workers more intensively: “if you want to keep your job, worker harder” and “unless you work harder, you will lose your job”. 30% of the workforce work longer than 48 hours a week, with 39% reporting an increase in working hours. Between 2000 and 2002 alone, the number of men working more that 60 hours per week rose from one in eight to one in six. The number of women working long hours has doubled. 50% of workers report inadequate or very inadequate staffing levels and as production and quality suffer, performance appraisal systems are introduced, causing more stress and worry. A major source of job insecurity (which speaks volumes) is the distrust employees have of their bosses: few employees believe their managers have any loyalty towards them. The longer we remain in a state of insecurity the more our physical and mental well-being deteriorates.

FLEXIBILISATION AND CASUALISATIONFlexibilisation is often presented as the creation of flexible working patterns when it is, in fact, the imposition of a flexible attitude among workers as to who controls our lives. It is also presented as both necessary (to the company’s productivity) and beneficial (to workers) as if the two could ever be compatible. We share in the company’s success only to the extent the bosses allow, and not according to our effort in creating it. Many employees, when asked, have no objection to flexible hours and working but it is the imposition of flexibility that provokes so much discord and rancour. Interestingly (and not surprisingly), those with interesting jobs are greatly in favour of flexible working. For them it means time with their children and a reduction in childcare costs. It means more leisure and quality time. They claim to be able to work smarter and harder. Study after study show, however, that this choice is not open to working class people in dead-end type jobs. Why well-paid and well-rewarded professionals, for instance, need this kind of benefit from their bosses to work hard is not explained. Nor is it explained why such freedom to choose when and how to work has a reverse effect on the ‘lower orders’, for whom long hours, poor pay and the threat of the sack seem to be the only way to get them to work! The working class response to flexibilisation a high labour turnover, absenteeism, low commitment and poor performance is matched by the reduction in benefits, performance management techniques and rigorous monitoring of work and working.

The same applies to casualisation, the process by which the power of employers to give or withhold employment (and with it the means to live). Many bosses are introducing ‘zero hour’ contracts, where there is no guarantee of work and you are permanently on-call. This has the benefit (to the bosses) of the worker not having any rights or protection under the law. The risk associated with the uncertainties of unplanned economies, of having to pay idle workers for instance, is transferred to the workers themselves. So much for the daring entrepreneur who risks all to create wealth for the many! Many millions of jobs have always been or are rapidly becoming casualised. The principles of the free market, where value is entirely subjective, nothing is guaranteed and the devil take the hindmost are being applied to the labour market. And yet, in a society where life is work, doesn’t our failure to have and to hold onto employment condemn us to failure as human beings? Read any tabloid newspaper, listen to any right-wing politician or pundit and the answer is, yes.

MCDONALDISATION“Workers and consumers are the miserable servants of machines and their endless demands”.McDonaldisation (the modern form of Taylorism, though management courses will not mention either word) is a system of producing goods and services in which the process is broken into its smallest part, systematically analysed, re-engineered to maximise profit and replicated in each and every working environment that produces those goods. Making things becomes a series of entirely independent, discrete, controllable actions, eliminating independent thought and creativity.

We become alienated from the process, required to perform a series of meaningless tasks. Such alienation from the work produces depression, anger, an unthinking and uncaring remoteness from other people.

Everywhere this process is used the bosses are happy with the amount produced but appalled by its low quality. Their only solution is to tightly control and quarantine workers: visit some of the industrial gulags of Indonesia, Malaya or China, for instance. The labour turnover in these factories is evidence of the determination of people to resist their exploitation. The bosses get rid of any worker who shows signs of resistance or who are too demoralised to produce efficiently. Their awareness is a disease that makes them unfit for work or to be around other workers they might infect: with knowledge of, anger towards and contempt for the bosses.

This system is also often known as Toyotism, after the Toyota, Japan factory system introduced in the 1960s and 1970s. The level of control over workers has been intensified by the introduction of individual work contracts and other processes that impose obligations to produce on the individual while weakening collective agreements and relationships creating what is known in Europe as the ‘diffuse factory’. What is new about Toyotism is "just-in-time" production and prompt reaction to market requirements; the imposition of multi-jobbing on workers employed on several machines, either simultaneously or sequentially; quality control throughout the entire flow of production and real-time information on the progress of production in the factory. Production is often halted and work-teams, departments or even the whole factory called to account. Anybody who shows a waged-worker's indifference to the company's productivity requirements and decides not to join "quality control" groups etc, is stigmatised and encouraged to leave.

The same system is applied to the commodities that are used in the process with every stage of how they are produced and processed minutely regulated. A cow is not a living creature but a sack of usable and unusable meat, fat and gristle. How the useful is divided from the not-so useful is a science in itself. Increasingly consumption and leisure are being ‘McDonaldised’. The places where we seek pleasure are increasingly the same, we expect to be able to find the same brand names throughout the world. We laugh at the same time and at the same jokes. Culture is increasingly global but it also increasingly mass-manufactured and distributed, designed for mass appeal, consumed not created, a thing that is done to us, doled out in pieces to audiences that are happy to feed for awhile instead of thinking.

COMMODIFICATIONWork used to be a purposeful and meaningful activity. There was spiritual satisfaction in working and co-operating to meet the needs of ourselves, our families, our people. People chose the work they did if they could and invested much of their personality and abilities in the making and production of useful, better or beautiful things. Today, the pre-eminence of consumption as a social good and conferrer of social status on us as individuals has made the product far more important than the producer (witness the social cachet of a Nike trainer over the sweated Indonesian who made it). Work has ceased to have a personal value for those who toil. In many cases it does not have a social value to society (witness the amount we discard or the sheer quantity of junk goods we produce). Large amounts of work is simply about the reproduction of capitalism on a daily basis think about the trillions of dollars traded on the stock markets for instance and why it is being done. It matters only because this is the means by which capitalism justifies itself and produces the means money for its own continuation. The activity produces nothing, except money, whose social value is zero. Work only matters in terms of what is produced the commodity - and the social and personal value of what is produced to the person consuming it. If you don’t believe us, why are so many important jobs like nursing rewarded so badly? Our labour, the portion of time we spend being ‘socially useful’ has become a commodity, whose value in the market is dictated solely by the whims of millions of other individual desires to possess, stimulated by the propaganda mills of capitalism, the advertising industry. Of course, many people realise this but are themselves trapped by the artificial need and desire to consume. We become our own gaoler! It is through consumption that the majority channel their aspirations to pleasure, to a sense of meaning and personal identity. Our aspirations to freedom have been transferred from the workplace to the rest of our lives but the commodification of personal life and leisure has simply built more cares around our life. The refusal to work must be accompanied by the refusal to consume (and vice versa), to participate in the reproduction of everyday life through the production and consumption of useless commodities via a commodified process: work.

ARGUMENTS AGAINST WORKWAGE SLAVERY

“Labour only sustains life by stunting it. Tell me how much you work and I'll tell you what you are”.When wage-slavery began, and primarily men were drafted into the ranks of wage-slaves, wage-work was portrayed by the merchant and industrial classes as an emancipation from feudal bondage. Over the course of the 19th and 20th Centuries, many women started doing piecework at home and some began leaving home to take paid employment. Many reasons are suggested for this: war-created need for additional labour, movements of female emancipation, greater social aspiration and mobility, the decay of patriarchal culture. What is usually not talked about is the reduction in the value of wages offered to men throughout this period, which turned women into wage-workers. Women's opposition to patriarchal norms and their compulsion to take up wage-work have led many people argue that work outside the home is a liberating and rewarding experience for women, one that allows them to fully develop their intellectual and human potential, a liberation from domestic drudgery. But wage work in factories or workshops, in clerical positions, in schools & laboratories, in production or in retail stores involves regimentation, repetition, physical burdens and spiritual turmoil that are hardly liberating, creative, or fulfilling.

For working class women and men work is neither joyful nor creative. Wage-work is meaningless. Jobs are boring and repetitious, they provide no intellectual or spiritual rewards and provide no satisfaction. The severe regimentation of factory life, which now pervades all spheres of life, destroys vitality and intelligence. It is not paid work but rather free moments away from jobs and housework that give meaning to life. Labour, and how it is organised by the bosses, underpins contemporary relationships among people on every level of experience: whether in terms of the rewards it brings, the privileges it confers, the discipline it demands, the repression it produces or the social conflicts it generates.

COMPULSION AND DEGRADATION

“In a ton of work, there's not an ounce of love”The early factory introduced no sweeping technological advances more important than the abstraction, rationalization and objectification of labour, and its embodiment in human beings. The factory was not born from a need to integrate labour with modern machinery. It arose from a need to rationalise the labour process, to intensify and exploit it more effectively. The initial goal of the factory was to dominate labour and to destroy the worker’s independence from capital.

And what of the post-Fordist future? Technologies already present will restructure and stratify work, dividing labour power into a relatively restricted upper level of the super-skilled, and a massive lower level of ordinary doers and executors. It will continue to separate and divides labour power hierarchically and spatially and break the framework of collective bargaining. The process of accumulation will become more intense, and it is possible there will be a long period of capitalism without opposition: turbo-capitalism, marked by an unusual political stability. The post-Fordist worker will be an individual who is atomised, flexibilised, increasingly non-union, kept on low wages and inescapably in jobs that are always precarious. The state will no longer guarantee to cover the material costs of the reproduction of labour power and will further act to limit consumption. The majority sector of the non-privileged will be forced to cut back on its standard of living in order to survive. This may lead to resistance and the resurrection of traditional forms of organisation and collective action. We certainly hope so. For without it, the future for humanity as individual, thinking beings prompted by internal desires and needs and not artificially-created compulsions to work and consume (or not), is bleak indeed.

Anarchists desire to see humanity liberate itself from work, if by liberation we mean self-government. As well as hierarchy, the workplace created by power structures also helps to undermine our abilities. As Bob Black argues:

"You are what you do. If you do boring, stupid, monotonous work, chances are you'll end up boring, stupid, and monotonous. Work is a much better explanation for the creeping cretinization all around us than even such significant moronizing mechanisms as television and education. People who are regimented all their lives, handed to work from school and bracketed by the family in the beginning and the nursing home in the end, are habituated to hierarchy and psychologically enslaved. Their aptitude for autonomy is so atrophied that their fear of freedom is among their few rationally grounded phobias. Their obedience training at work carries over into the families they start, thus reproducing the system in more ways than one, and into politics, culture and everything else. Once you drain the vitality from people at work, they'll likely submit to hierarchy and expertise in everything. They're used to it." Historians and politicians ask us to accept that the productive advances unleashed by the factory system were worth the price of our spiritual degradation. The idea of ‘The End of History’ is built upon the notion that humanity has lost the ability to create new social relations and will remain largely content to remain for ever trapped in a liberal, bourgeois and capitalist society of abundance. Capitalism’s aim, because it fears the liberatory potential of the working class, is to continue the process of degradation until we are unable to resist. It seeks to create essentially inorganic beings, spiritually dead automatons. Insanity, irrationalism, alienation, anomie, the inability to empathise, to be more than functionally creative, the routinisation of exploration and adventure, these are symptoms of a deep and invidious illness deep in humanity’s soul which capitalism has spread amongst us.

This attempt to change the fundamental nature of humanity, and to enslave us, does not just occur in the workplace but exists at all levels of modern ‘civilisation’. Mass production and the compulsion to work is made possible only by vast bureaucracies, authoritarian ‘mega-machines’ of socialisation, investigation, compulsion, control and sanction. Capitalism reduces the worker to a mere machine operator, following the orders of his or her boss. And entirely soulless mass-produced objects create mechanically deadened people. It has created a constant process of alienated consumption, as workers try to find the happiness associated with productive, creative, self-managed activity in a place it does not exist the shopping mall or retail precinct.

To reverse this, we must re-conquer everyday life by destroying the state. Liberating technologies presuppose liberating institutions. The forms of resistance are as widespread and diverse as the means of control. In the factory, strikes, sabotage, work stoppages. In the community truancy, vandalism, protest, direct action, arson. And there are also positive actions as well. Acts of sabotage or work refusal (by phoning in sick, for instance) are rarely individual acts but collective ones, approved of and assisted by fellow workers. If the rule is silence, we communicate. If the command is speed up, we slow down. Resistance creates zones of freedom that we can extend and make permanent, creating within them the institutions the claimant’s union, the rank-and-file workers group, the direct action campaign that are the seeds of future liberation.

RESISTANCE IN THE WORKPLACEHere’s just some of the wonderfully inventive ways workers have found to defy the bosses and take back a little in time, dignity and self-respect that the bosses try to steal using the need for money to live.

WORK TO RULEEvery industry is covered by a mass of rules, regulations and agreed working practices, many of them archaic. If applied strictly they can make production difficult if not impossible. Many of these rules exist in any case to protect management in the event of industrial accidents. They are quite prepared to close their eyes when these rules are broken in the interests of keeping production going. Even a modest overtime ban can be effective, if applied intelligently; it is particularly effective in industries with uneven work patterns. Here’s just one example of a work to rule in practice an effective tactic with little chance the bosses can do anything about it except suffer: When, under nationalisation, strikes [on the French railways] were forbidden, their syndicalist fellow-workers urged the railmen to carry out the strict letter of the law... One law tells the engine driver to make sure of the safety of any bridge over which his train has to pass. If after personal examination, he is still doubtful, then he must consult the other members of the train crew. Of course trains run late! Another law for which French railwaymen developed a sudden passion related to the ticket collectors. All tickets had to be carefully examined on both sides. The law said nothing about city rush hours!

GO SLOW

This is a very effective tactic where various industrial processes depend one upon the other and both supply and distribution are geared to continuous, steady rates of production, such as in the automotive or food packing industries. Here’s one example of a go-slow (which is an increasingly common tactic in the sweatshop factories of the developing world) from Fords at Dagenham, at the time one of the biggest car assemblers in the world: The company stated that the headliners had repeatedly refused to fit more than 13 heads in any one shift, saying that the management's request was unreasonable. Yet “they had in fact fitted each headlining in less time than allowed, and spent the remainder of the time between jobs sitting down. They took so long over each car that they prevented other employees on the line from performing their operations thus causing congestion and frequently leading to the lines being stopped and sometimes other employees being sent home. Shop stewards however, supported by the convener, had always maintained on these occasions that the employees concerned were working normally and refused completely, in spite of numerous appeals, to persuade their members to remove restrictions”.

GOOD WORKOne of the serious problems facing militants in general and workers in the service industries in particular is that they can end up hurting the consumers (mostly fellow workers) more than the boss. This isolates them from the general mass of the population, which enables the authorities to whip up 'public opinion' against the strikers. One way round this problem is to consider techniques which selectively hurt the boss without affecting other workers - or better still are to the advantage of the public. The 'good work' strike is a general term which means that workers provide consumers with better service or products than the employer intended. One good side-effect of the good work strike is that it places the onus of stopping a service on the employer. Even if ‘good work’ leads to a lock-out of workers by the boss, service-users would still blame the employer rather than the worker. And lock-outs can be avoided by ‘wildcat’ good working: suddenly, without notice, and for limited periods - repeated at intervals until the bosses cave in. In New York City restaurant workers, after losing a strike, won some of their demands by heeding the advice of organisers to "pile up the plates, give 'em double helpings" and figure bills on the lower side. You can imagine similar situations in other industries, for instance postal workers behind a counter only accepting unstamped letters or people working checkouts refusing to work the tills. Here’s a final example: Lisbon bus and train workers gave free rides to all passengers. They were protesting because the British-owned Lisbon Tramways Company had not raised their wages. Today conductors and tram drivers arrived at work as usual, but the conductors did not pick up their money satchels. On the whole the public seems to be on the side of these take-no-fare strikers.

OPEN MOUTHSometimes telling people the simple truth about what goes on at work can put a lot of pressure on the boss. Consumer industries (restaurants, packing plants, hospitals and the like) are the most vulnerable. There is not a lot the bosses can do about ‘open mouth’ action other than improving conditions. There is nothing illegal about it, so the police cannot be called in. It also strikes at the fraudulent practices which business for profit is based on. Commerce today is founded on fraud. Capitalism's standards of honesty demand that the worker lies to everybody except the boss. In the food industry workers, instead of striking, or when on strike, can expose the way food is prepared for sale. In restaurants, cooks can tell what kinds of food they are expected to cook, how stale foods are treated so they can be served up. Dishwashers can expose how 'well' dishes are washed. Construction and factory workers can alert newspapers and health and safety inspectors to the shoddy materials being used or cheating on safety regulations. Workers in public transport can tell of faulty engines, brakes, and repairs.

THE SICK INThe sick-in is a way to strike without striking. The idea is to cripple your workplace by having all or most of the workforce call in sick on the same day or days. Unlike the formal walk-out, it can be used effectively by departments and work areas instead of the whole workplace, and because its usually informal can succeed even where no union exists to organise it. At certain times, just the hint of ‘flu doing the rounds’ and the likelihood of it spreading to important areas of work can work wonders with a stubborn boss or supervisor. Even workers contacting the personnel office to see how much sick time they have available can send a powerful message.

TAKING CHARGE OF WORKSometimes the way to get what you want is to take it. This requires better and stronger organisation than any other direct action method but is also a powerful weapon in the worker’s arsenal. When workers decide that they are going to do what they want to do, instead of what the employers want them to do, there is not a lot the employers can do about it. There have been many examples of this taking place, from timber-felling in the USA, the heavy industries of Italy and South America and the automotive factories of USA, Britain and Europe. Here’s an example: A strong IWW Marine Transport Workers Union existed on trans-Atlantic shipping out of the port of Boston. One of the main grievances of the workers on these ships was the quality of the food served aboard ship. Acceptable menus were decided upon and published by the Union. The cooks and stewards, being good union members, refused to cook anything except what was on the menus - to the satisfaction of everyone except the bosses. But because work is often made up of a series of activities, involving different kinds of workers, it must be carefully co-ordinated and there must be high levels of solidarity between workers. This often requires there to be a strong union which can become just as much a ‘manager’ of shit work as it is the protector of liberated work.

OCCUPATIONS AND SIT INSSit-Ins are relatively restricted and passive and are similar to ‘go-slows’ and ‘slow-downs’, only with a clear physical expression people stop work and sit down. Occupations are more positive actions, actually to take over a plant and deny access to the management. The latter needs a high level of militancy and solidarity, as well as good rank-and-file organisation. Unity of purpose is essential for a successful Sit-In. While there is a fairly long record of sit-ins in Britain there have been few large-scale factory occupations such as are common in both France and Italy. Occupations require a high level of militancy and organisation on the part of the workers concerned. It is doomed if the factory remains isolated from the rest of organised labour, the working class and community generally but in the right conditions, it can be dynamite. What is needed is mass involvement. Workers should not be presented with a plan: an effective occupation must be preceded by departmental and mass meetings to plan the occupation, and lots of propaganda.

SABOTAGEWorkers and the work they do are a commodity, to be bought and sold like everything else. And in the marketplace, a low price often means shoddy goods. Why shouldn’t the same rule apply for workers? For low pay and bad working conditions, inefficient work. Working class sabotage is used more often than you would think. Although often used by frustrated individuals, it is most effective - like all direct action tactics - when all or most of the workers on a job are in on it. Here’s an example: When [the line] got over sixty, say, someone would just accidentally drop a bolt in the line and as soon as it worked its way round to the end, bang, the line would stop. Then there would be a delay and everybody would take their break. The same sort of thing goes on in every industry: neglecting to maintain or lubricate machinery at the correct intervals, punching buttons on complicated electronic gear in the wrong order, putting pieces in the wrong way, running machines at the wrong speeds or feeds, dropping foreign bodies in gear boxes, 'technological indiscipline': each industry and trade has its established practices, its own traditions.

THE STRIKEEven the traditional unofficial walkout can be made much more effective than it normally is. The participation of the ordinary worker is often limited to attending the occasional mass meeting. They then stay at home, in isolation, watching the progress of their own dispute on the TV. Bosses have got wise to this tactic, and governments have begun to threaten unions with sequestration and deny hardship benefits to striking workers. Workers have responded with ‘guerilla’ strikes, involving different workers and without any fixed pattern minimise the cost of strikes to the workers yet maximise their disruptive effect. There is the chessboard strike, where every other department stops. The brushfire or articulated strike, which, over a period, rolls through every key section of a works. The pay-book strike, where every worker whose payroll number is odd goes on strike on certain days, with even numbers on strike on the other days. And strikes where blue-collar workers down tools in the morning but return after lunch, only to find that the white-collar workers and foremen are now out, making all work impossible thus achieving a full day's stoppage for only half a day's loss of pay.

INFORMAL RESISTANCEOne of the greatest unsung stories of the industrial working class is that of resistance at the point of production. Work is so unpleasant that it is not surprising it is resented. Informal resistance- in the form of piecework ceilings, agreements among workers as to what constitutes a fair day's work and the refusal by workers to participate in their own exploitation - is what makes the difference between potential and actual production. Informal resistance and its effect on ‘productivity’, explains the steady and massive expansion of work-study, job evaluation, quality control, inspection, etc. Management also tries to solve this problem by introducing 'workers participation', to motivate their employees to identify with the interests of the company. In the long term all these measures will fail, as the basic problem, boring, unpleasant and often dangerous work, will not be removed.

WORK IN THE FREE SOCIETYFreedom begins where work endsThe ideology of work has begun to be challenged by recent changes in capitalism itself, by chronic mass unemployment and under-employment, the phenomenon of temporary and casual work, short-term contracts and flexibility. The notion of a job for life has become a thing of the past for most working people outside the so-called professions. Work is transitory, fragmented and periods of unemployment regarded as a natural condition. Many young working class people have never experienced the ‘dignity’ that labour is supposed to bestow and those who have never known the ‘world of work’ feel little guilt in not being part of it. Work as the basis for the way capitalism integrates people into society in order to control them is being undermined by chronic global economic crises caused by the radical restructuring of national economies in the search for profit (World Bank, WTO, Doha et al) and new technologies which are making certain classes of workers entirely redundant.

Where does this leave libertarian revolutionaries and our vision of social change? Will our arguments for a society without ‘employment’, without bosses and wage labour, make more sense to working class people for whom work has already become an unendurable means to an end, and for whom work has little meaning? Is there the possibility that a weakening of workers’ identification with their ‘occupation’ will bring about a weakening of their identification with the status quo? Or maybe the atomisation of large sections of the working class by the capitalism’s continuing development will cause a further decrease in class consciousness? Whatever the consequences of the decline of the work ethic and ideology, it is certain that wage labour will remain an alienated and alienating experience for those who are forced to take part in it and the exploitation inherent within work under capitalism will not go away.

The only solution is to reclaim for ourselves the right to work when we want to, doing what we want to do, when we want to do it, or to not work at all! But this emancipation from the crushing coils of wage slavery may meet an individual need for freedom but does nothing to end the destructive and malign institution that is capitalism today. After all, there are plenty more potential wage slaves where you come from! No, liberation from work must be a collective, global act, involving millions upon millions of toiling people, people who for a day, a week, a month or however long it takes, refuse to work and begin destroying the means by which capitalism makes us work.

This general and social strike is our aim, the refusal of work by all working people, for all time. It will be, we hope, a gentle insurrection, a welling up of anger and despair and the creation of a stubborn and unstoppable desire for freedom. We will take our hands from the plough and the loom, rise up from our desks, cast off our boots and overalls, walk out of the hotels and restaurants, leave the factory and office, meeting with others to join in their refusal to work as they celebrate ours.

And if this is a global act, how can the capitalist class resist us? We know how to live with nothing, do they? The working people of the world get by with no money and little food, without power and water for weeks on end, without servants or holidays or chauffeurs. We don’t need them. They need us, to work. And if we refuse to work, they have no power to compel us. And so, we mustn’t strike for this or that, for 5% here or 10% there, things that be granted today and taken back tomorrow. Our refusal to work must be for freedom from work, and that alone, for freedom, once taken, can never be reclaimed.

Once capitalism has been destroyed, we can set about the exciting task of fulfilling our individual potential and shaping this new community. Of course, in a world that may have been disrupted by the process of revolutionary war, we will first need to ensure that we can feed and shelter everyone. This need not be the brutal task the counter-revolutionaries try to scare us with. In the world there are more than enough buildings and food to provide for everyone. What matters, of course, is to distribute these fairly, using newly seized communications such as radio stations, roads and railways.

Capitalism creates a culture in which it is a virtue to work, to strive to outdo or overcome, to contribute on society’s terms. We fight against the false logic of capitalist thought, which uses concepts as 'Progress', 'Growth', and 'Development' to justify its compulsion of people (by open and more subtle means) to work and work harder. The economic system is not something that should hurtle out of control but must, like technology, be subordinated to human need. This leads us to question the work ethic and the nature of work so we wrote this pamphlet. The revolution will fundamentally transform the nature of work. Where we live and work will be considerably altered. We will re-organise industry so that we only produce what is socially useful. We will introduce the ecological management of production and consumption, balancing the needs of society against the desires of its members. And in doing this we will massively reduce the amount of work that must be done to sustain society, work that itself will be freely chosen, increasing the time available to us for all the other things that make living worthwhile.

VOLUNTARISMWork will be a voluntary act, a personal choice to work or not to work, to work now or later, to work hard or slowly or carefully, with our hands or our minds or both. Because the meaning of work lies within the personal benefit to ourselves and the social benefit to others, it must be freely chosen. Nothing in society will compel us to do work we do not want to do in ways we find wrong or alien to ourselves. Nor will there be any incentives to do this or that work. There will, for instance, be no more prestige or status attached to one social function compared to another and where a person can do the work, there will be no artificial barrier (a union card, a qualification, a tribal affiliation, a greased palm) to doing it. With this freedom comes a generalised responsibility to ensure society maintains itself. If the free society is generally beneficial to all, we will want to keep it going. We will need to develop a sense of what needs to be done and whether and how we can contribute to that aim. In part that will come, as it does now, from education and socialisation, the millions of interactions we have with our fellow human beings that shape who we are and define what we want to do with our lives. But the key part in all this will be ourselves, our social conscience, our sense of what is best for both our society and ourselves. The measure of our society and its worth to humanity will be the extent to which what needs to be done is done, by free choice and without compulsion and the pleasure humanity gets in the doing of it.

CO-OPERATIONAs revolutionaries we argue for egalitarian structures accountable and accessible to all. It seems most likely that these structures will emerge from the workers and community councils that the working class create during the Revolution. We also foresee that a federal structure will emerge globally to co-ordinate such things as the production and distribution of resources, determining the kinds of things that need to be done and how to get them done, with decisions being taken at the lowest appropriate level: the individual worker, the small craft shop, the neighbourhood, the town, industry or region and so on. Agriculture and industry will be undertaken by communities that are part of local and global networks distributing their produce.

PERSONAL CHOICESpecific examples of changed social relations will serve to show what we mean by social revolution. No human being will be prepared or compelled to do particular kinds of work. People may choose to continue a tradition of particular kinds of work, going into the same kinds of work as their peers (on the one hand) or may choose an esoteric form of work they spend their whole life learning how to do. Women will not have the maintenance of the home and child-rearing as their major social function, because such tasks will be the responsibility of the whole community. Children will do the work they can and want to do (and also have time for education and leisure) as soon as they can.

It is a fundamental belief of anarchist communists that the working class already have the skills needed to run society. Not everyone has all of these, of course, and equality does not mean that we all take it in turns to perform heart surgery! Some specialisation will be necessary. We will work as we want, so long as the thing we are doing at the time meets our personal and social needs. If you want to work long and hard at a particular task you are free to do so, gaining the fulfilment such action brings. If you wish to work a bit here, then play, then work again at something else, changing jobs as you like, travelling to different places to do it, working with different people as your mood determines, then do it.

The only lesson society will teach its members is that there are times to work and to rest, to labour and to play, to work hard or a little, to do what needs to be done sometimes and what we want to do a lot, to use our hands or our brains or both as needed, to find the value in every activity and to have enjoyed the doing and the not-doing in equal measure.

PRODUCTIVE WORKWork will be more enjoyable because, unlike capitalism, it will have a point to it and because we will work in ways that maximise fulfilment, not profit. Less pleasant but none the less necessary tasks will be shared out entirely equally and the rest of our time can be spent in enjoyable and creative pursuits. Of course, fields will have to be ploughed, drains cleaned and domestic work performed, but no one will be 'a farm labourer', a 'sewage worker' or 'a housewife', because these task will be shared out equally and performed in collectively run farms, workplaces, launderettes and crèches etc, and occupy the minimum of time for each person (unless they like doing them!). In addition, these tasks will no longer be performed for a boss, a council bureaucracy or a husband, because we will not be answerable to any more powerful individual but to our anarchist communist society, i.e. each other.

Don’t get us wrong: we are not stakhanovites who endlessly extol the pleasure and virtues of toil! If the free society of the future can only be sustained by long hours of drudgery and the self-abasement of the people to the god ‘production’, we want none of it. But we know, because it has been proven over and over again, that the amount of necessary work that will be shared amongst those people able to do it amounts to no more than 2-3 hours, leaving the rest of the day for play, creativity, sex, idleness, socialising, recreation, study, whatever we want.

THE PLEASURE OF WORK: THE WORK OF PLEASURE

The liberation of work can only come about with the liberation from work, from the capitalist reduction of life to workMost work under capitalism is mindless and pointless, unless you are a boss. All activity after the Revolution will take place not for profit or the maintenance of the status quo, as it does now, but for the fulfilment of the individual, although never to the detriment of society. There will be no place for useless work such as the production of consumer goods for profit or the maintenance of social control because these 'normal' aspects of society will be irrelevant after the Revolution. Each person will therefore have more time on their hands, but this is fundamentally different to 'unemployment' because no one will be 'employed'. Productive activity is an important way of developing our inner-powers and expressing ourselves, in other words being creative. As Alexander Berkman argues:

"We do not live by bread alone. True, existence is not possible without opportunity to satisfy our physical needs. But the gratification of these by no means constitutes all of life. In a sensible society…….. [t]he feelings of human sympathy, of justice and right would have a chance to develop, to be satisfied, to broaden and grow."Anarchists desire to change the nature of both work and life and create a society based upon freedom in all aspects of life. In the free society, the contribution a person makes to society or the social value of work will not be measured in economic terms as it is under capitalism. It will not be measured at all. What matters is that each individual feels that the work they do is personally fulfilling. If it makes a positive contribution to society as well, this is a bonus for us and you.

Work will become, primarily, the expression of a person's pleasure in what they are doing and become like an art - an expression of their creativity and individuality. Work as an art will become expressed in the workplace as well as the work process, with workplaces transformed and integrated into the local community and environment.

We hope that this short pamphlet about explains why anarchists want to abolish work and seek to escape the imposition of work upon us and upon the toiling millions of the earth. We also hope that it leads you to begin to question your own involvement in the world of work and stimulate a desire to work for the liberation of those millions. The future will decide upon the nature of work in the future, of work as a creative, liberating, productive and fulfilling activity. To us falls the task of breaking our chains. What our children make from them is their work and the only work that will matter in the free society of our future.

Text taken from http://www.prole.info