.

Eugenics and Social Control"Whatever the Jukes stand for, the Edwards family does not. Whatever weakness the Jukes represent finds its antidote in the Edwards family, which has cost the country nothing in pauperism, in crime, in hospital or asylum service."-Albert E. Winship,

Heredity: A History of the Jukes-Edwards Families

Boston, 1925

By Margaret QuigleyDuring the first three decades of this century, a small but influential social/scientific movement known as the eugenics movement extrapolated from the new science of human genetics a complex set of beliefs justifying the necessity for racial and class hierarchy. It also advocated limitations on political democracy. The eugenicists argued that the United States was in immediate danger of committing racial suicide as a result of the rapid reproduction of the unfit coupled with the precipitous decline in the birthrate of the better classes. They proposed a program of positive and negative eugenics as a solution. Positive genetics would encourage the reproduction of the better-educated and racially superior, while a rigorous program of negative eugenics to prevent any increase in the racially unfit would include compulsory segregation and sterilization, immigration restriction, and laws to prohibit inter-racial marriage (anti-miscegenation statutes).

I will argue that the eugenics movement of the early 20th-century was primarily a political movement concerned with the social control of groups thought to be inferior by an economic, social, and racial elite. I reject the contention that the movement was primarily scientific and apolitical. I have looked here primarily at the organized eugenics movement and its leading figures, rather than at the average rank-and-file follower within the movement.

My interest in the eugenics movement stems from my fear that the basic principles of the eugenics debate, even its most discredited aspects, are resurfacing in the 1990s. To revisit the eugenics movement of the early 20th-century is to be reminded of the harm the movement intended toward those members of society least able to defend themselves. History, in this case, may help to provide an antidote to contemporary manifestations of eugenicist arguments--the I. Q. debate and the right's anti-immigrant campaign.

Any historical appraisal of the eugenics movement needs to step carefully to avoid imposing the values of the late 20th-century upon eugenicists, especially concerning the question of motivation. The legitimate, scientific framework of the eugenics movement, a mainstream view at the beginning of the century, has been for the most part abandoned by scientists in the years since then.

Similarly, to a great extent, racialist thinking, and in particular white supremacy, was neither questioned nor challenged among the white-dominated intelligentsia of the time. At the same time, the fact that white supremacist views were more acceptable in white society at the turn of the century still allows for gradations of focus and virulence; the question of the extent to which hereditarian arguments may have functioned as a pretext for a movement primarily concerned with the continuation of social and political dominance by upper-class, Protestant men of Anglo-Saxon background is unavoidable.

The roots of the eugenics movement have been traced variously to social Darwinism; social purity, voluntary motherhood, and the perfectionists; the naturalist tradition; Malthus and the neo-Malthusians; and the Progressive political and social movement.

This paper emphasizes instead that the roots of the eugenics movement can be traced to the 19th-century scientific racism movement. "Scientific racism" is a term capable of diverse definitions. For this discussion, I have adopted a slightly modified version of historian Barry Mehler's definition:

"[Scientific racism is] the belief [often based on skin color, country of origin, or economic class] that the human species can be divided into superior and inferior genetic groups and that these groups can be satisfactorily identified so that social policies can be advanced to encourage the breeding of the superior groups and discourage the breeding of the inferior groups."It is possible to argue that notions of control by a racial and economic elite were key to the eugenics movement without embracing reductionist or conspiratorial theories that do damage to the diversity and scope of the movement.

It has been the diversity of the eugenics movement--the wide range of followers it was able to encompass--that has proved most difficult to explain. The eugenics movement was not monolithic: conservatives, progressives, and sex radicals were all allied within a fundamentally messianic movement of national salvation that was predicated upon scientific notions of innate and ineradicable inequalities between racial, cultural, and economic groups.

These scientific notions tended to maintain the status quo by obscuring the racial and class basis of poverty and advancement in the United States. The middle- and upper-class professionals of Anglo-Saxon descent who were leaders in the eugenics movement acted in and out of their own interests.

Those interests led to the development of a political program in which an extreme economic conservatism was marked by a virulent anti-communism linked to an embrace of the untrammeled, unregulated capitalist state. Some eugenicist leaders rejected democracy in favor of the corporate state and, in the 1920s and 1930s, several leaders of the eugenics movement were active in the promotion of German and Italian fascism.

The eugenics movement put forth a coherent, consistent social program in which eugenical sterilization, anti-immigrant advocacy, and anti-miscegenation activism all played crucial roles in the primary eugenicist goal of advancing social control by a small elite. Particularly now, when familiar eugenicist arguments echo within contemporary scientific and political circles, questions of motivation and intent are compelling.

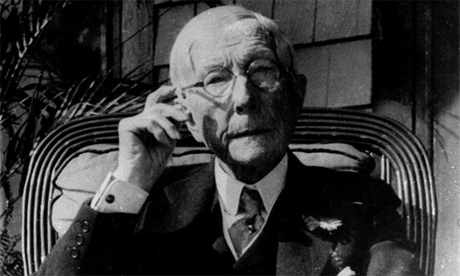

Background of the MovementThe American eugenics movement came into being primarily through the efforts of Charles Benedict Davenport, a biologist with a Ph.D. from Harvard University. While at Harvard as an instructor in the 1890s, Davenport became familiar with the early eugenicist writings of two Englishmen, the independently wealthy Francis Galton and his protégé Karl Pearson.

By 1869, Galton had published several articles and a book, Hereditary Genius, which argued that human traits, and particularly great ability, can be inherited from previous generations.

It was not until 1883 that Galton coined the term "eugenics," and it was 1904 before he formulated his classic definition of eugenics as "the study of agencies under social control that may improve or impair the racial qualities of future generations, either physically or mentally."

Galton had been tremendously influenced by his cousin, Charles Darwin, whose study of human evolution, The Origin of Species, was published in 1859. The eugenicists, led by Galton in England and Davenport in the US, were fascinated more by the idea of the inheritability of human traits than by Darwin's focus on the evolution of species over time.

Charles Darwin thought highly of his cousin's book on the inheritance of genius; he wrote, "I do not think I ever in all my life read anything more interesting and original."

Eugenicists originally believed in the inheritability of virtually all human traits. Charles Davenport's work provided a typical list of hereditary traits: eye color, hair, skin, stature, weight, special ability in music, drawing, painting, literary composition, calculating, or memorizing, weakness of the mucous membranes, nomadism, general bodily energy, strength, mental ability, epilepsy, shiftlessness, insanity, pauperism, criminality, various forms of nervous disease, defects of speech, sight, hearing, cancer, tuberculosis, pneumonia, skeletal deformities, and other traits.

Davenport is reported to have hypothesized that thalassophilia, love of the sea, was a sex-linked recessive trait because he only encountered it in male naval officers.

For the most part, the eugenicists emphasized inheritance and trivialized the importance of environment. Stanford University president David Starr Jordan, an important American eugenicist, was typical in his dismissal of environmental arguments:

"No doubt poverty and crime are bad assets in one's early environment. No doubt these elements cause the ruins of thousands who, by heredity, were good material of civilization. But again, poverty, dirt, and crime are the products of those, in general, who are not good material. It is not the strength of the strong, but the weakness of the weak which engenders exploitation and tyranny. The slums are at once symptom, effect, and cause of evil. Every vice stands in this same threefold relation"In the same vein, another eugenicist wrote:

"The. . .social classes, therefore, which you seek to abolish by law, are ordained by nature; that it is, in the large statistical run of things, not the slums which make slum people, but slum people who make the slums; that primarily it is not the church which makes people good, but good people who make the Church; that godly people are largely born and not made. . . ."The US eugenics movement grew out of the American Breeders' Association (later the American Genetics Association), which was founded in 1903 to apply the new principles of inheritance to the scientific breeding of horses and other livestock. In 1906, at Davenport's urging, the ABA established a Eugenics Section (later the Committee on Eugenics). Stanford University president David Starr Jordan chaired the committee and Davenport was its secretary. These men and others active in the Committee on Eugenics (including the founders of the Nativist Immigration Restriction League, Robert DeCourcey Ward and Prescott F. Hall; Henry H. Goddard and Walter E. Fernald, who both joined a subcommittee on feeble-mindedness; Alexander Graham Bell; and Edward L. Thorndike) would form the core of the eugenics movement for the next 25 years.

The organized eugenics movement revolved around Davenport's Station for Experimental Genetics, at Cold Spring Harbor on Long Island, New York, which itself came increasingly to focus on eugenical studies. In 1910, the Eugenics Record Office was established with Davenport as director and Henry H. Laughlin, key eugenicist and leader of the eugenical sterilization movement, as its superintendent. Two other important eugenics organizations were the Eugenics Research Association (with Davenport and Laughlin as its key members) and the American Eugenics Society (AES).

The Eugenics Research Association described itself as a scientific rather than political group and the AES, established in 1921, was visualized as the propaganda or popular education arm of the eugenics movement.

The eugenics movement advocated both positive and negative eugenics, which referred to attempts to increase reproduction by fit stocks and to decrease reproduction by those who were constitutionally unfit. Positive eugenics included eugenic education and tax preferences and other financial support for eugenically fit large families. Eugenical segregation and, usually, sterilization (a few eugenicists opposed sterilization); restrictive marriage laws, including anti-miscegenation statutes; and restrictive immigration laws formed the three parts of the negative eugenics agenda.

Virtually all eugenicists supported compulsory sterilization for the unfit; some supported castration. By 1936, when expert medical panels in both England and the US finally condemned compulsory eugenical sterilization, more than 20,000 forced sterilizations had been performed, mostly on poor people (and disproportionately on black people) confined to state-run mental hospitals and residential facilities for the mentally retarded. Almost 500 men and women had died from the surgery. The American Eugenics Society had hoped, in time, to sterilize one-tenth of the US population, or millions of Americans. Based on the American eugenical sterilization experience, Hitler's sterilization program managed to sterilize 225,000 people in less than three years.

Eugenics' Racial BiasFrom the beginning, the eugenics movement was a racialist (race-based) and elitist movement concerned with the control of classes seen to be socially inferior. In proposing the term eugenics, Galton had written, "We greatly want a brief word to express the science of improving the stock. . .to give the more suitable races or strains of blood a better chance of prevailing speedily over the less suitable than they otherwise would have had."

Galton believed that black people were entirely inferior to the white races and that Jews were capable only of "parasitism" upon the civilized nations.

Karl Pearson, Galton's chief disciple, shared his racial and anti-Semitic beliefs. For example, in 1925, Pearson wrote "The Problem of Alien Immigration into Great Britain, Illustrated by an Examination of Russian and Polish Jewish Children," which argued against the admission of Jewish immigrants into England.

In the US, the eugenics movement started from a belief in the racial superiority of white Anglo-Saxons and a desire to prevent the immigration of less desirable racial stocks. In 1910, the Committee on Eugenics solicited new members with a letter that read, "The time is ripe for a strong public movement to stem the tide of threatened racial degeneracy. . . .America needs to protect herself against indiscriminate immigration, criminal degenerates, and. . .race suicide." The letter also warned of the impending "complete destruction of the white race."

Eugenical News, which was published by the Eugenics Research Association and edited by Laughlin, welcomed racist and anti-immigrant articles. At the Second International Congress on Eugenics in 1921, one of the five classifications of exhibits was "The Factor of Race."

Similarly, the American Eugenics Society's "Ultimate Program," adopted in 1923, placed "chief emphasis" on three goals:

a brief survey of the eugenics movement up to the present time;

working out and enacting a selective immigration law;

securing segregation of certain classes, such as the criminal defective.

The Eugenics Research Association included among the major issues its members addressed "[im]migration, mate selection. . .race crossings, and. . .physical and mental measurement."

When the World War I-era IQ testing of all soldiers indicated that almost half of all white recruits were morons according to the newly developed Stanford Binet test, as were 89 percent of all black recruits, the eugenics movement seemed more important and believable.

Although some commentators questioned the validity of the test, and noted that questions on such topics as the color of sapphires and the location of Cornell University might reflect qualities other than intelligence, the statistics, when released, created great anxiety and gave the eugenics movement a substantial boost.

19th-Century Scientific RacismThe scientific racism movement of the mid-nineteenth century provided a number of important legacies to the eugenics movement. American scientific racism was primarily preoccupied with the attempt to establish that blacks, Orientals, and other races were in fact entirely different species of "man," which the scientific racists claimed should be seen as a genus, rather than a species. The theory that the integrity of the human species derived from the creation of one Adam and one Eve was called monogenism or specific unity; monogenists believed that the races arose as a result of the degeneration of human beings since creation. The separate races were essentially the same human material, but different races had degenerated to different extents. Polygenists, by contrast, believed that the races were created separately in a series of different creations. The separate races were entirely different animals. The mid-century theory of polygenism, or specific diversity, was one of the first scientific theories largely developed in the US and was approvingly called "the American School of anthropology" by European scientists.

Harvard Professor Louis Agassiz, a prominent natural historian of the 19th-century, was the most important promoter of polygenism. Agassiz, an abolitionist, insisted that his adoption of polygenism was dictated by objective scientific investigation. Nevertheless, historian Stephen Jay Gould's translation of Agassiz's letter to his mother in 1846 shortly after his emigration to the US, reveals a profound, visceral aversion to blacks.

Not surprisingly, Agassiz was also passionately opposed to racial miscegenation. He believed that racial inter-mixture would result in the creation of "effeminate" offspring unable to maintain American democratic traditions. Agassiz wrote:

"The production of half-breeds is as much a sin against nature, as incest in a civilized community is a sin against purity of character. . . .No efforts should be spared to check that which is abhorrent to our better nature, and to the progress of a higher civilization and a purer morality."In part because the classic definition of a species revolved around the ability to mate and produce children with each other but not with others, and in part because of a drive toward racial hierarchy, the questions of hybridization and fecundity were of great import to the early American scientific racists. For the eugenicists, these questions were also tremendously important. Much of the early scientific racist rhetoric on hybrids later reappeared in eugenicist writings where it came to form the basis of eugenicist arguments against racial miscegenation. The early concern with fecundity fueled later eugenicist claims that differential racial fecundity was leading to white racial suicide.

The eugenicist recapitulation of earlier scientific racist arguments was not cursory, but deep and enduring. In one of many examples, a 1925 bibliography on eugenics published by the American Eugenics Society recommended the book, Uncontrolled Breeding, Or Fecundity versus Civilization.

At the First International Congress of Eugenics in 1912, author V. G. Ruggeri, despite his concern with race-mixing, put forth Mendel's monogenism to bolster his own argument in favor of monogenism; and Lucien March spoke on "The Fertility of Marriages According to Profession and Social Position." The opening of Raymond Pearl's lecture on "The Inheritance of Fecundity" made clear his position within this tradition:

"The progressive decline of the birth rate in all, or nearly all, civilized countries is an obvious and impressive fact. Equally obvious and much more disturbing is the fact that this decline is differential. Generally it is true that those racial stocks which by common agreement are of high, if not the highest, value to the state or nation, are precisely the ones where the decline in reproduction rate has been most marked."Family Studies, Social Darwinism, and Race SuicideEugenical family studies were an important component in the movement's political development; family studies functioned as an objective, scientific basis for the twin myths of a feeble-minded menace and an impending white race suicide. The invention of feeble-mindedness, typically used as a term of art to cover broader issues related to social control, allowed the eugenicists to claim that social (and racial) classes were biological and hence immutable.

The first important eugenicist works in the US were a series of studies of American families supposedly plagued by hereditary feeble-mindedness, beginning with Richard Dugdale's exposition of the Jukes family, published in 1877.

All of the family studies claimed to prove that a single feeble-minded ancestor could (and did) result in generations of poverty-stricken and degenerate offspring. The families in the studies were rural families, of Anglo-Saxon, Protestant descent, and for the most part, their lineage dated to the colonial settlers. The families were remarkably similar to the eugenicist activists in these traits; the main difference between the two was the poverty of the rural families. The equation by the eugenicists of poverty with degeneracy was quite explicit. Eugenicists believed that poverty was no more than a manifestation of inner degeneracy. Charity was therefore unlikely to lead the pauper out of poverty and, in fact, misguided charity might prove very costly to society. In the heightened tone that is common to writers in the family studies, one eugenicist wrote, "It is impossible to calculate what even one feeble-minded woman may cost the public, when her vast possibilities for evil as a producer of paupers and criminals, through an endless line of descendants is considered."

Another writer said, for example, "A habit of irregular work is a species of mental or moral weakness, or both. A man or woman who will not stick to a job is morally certain to be a pauper or a criminal."

In the same vein, a third wrote, "Pauperism and habitual criminality are respectively passive and active states of the same disease."

Feeble-mindedness for the eugenicists was a designation that created a difference between the eugenicists and the families they studied. One group of social reformers described in detail the nature of the feeble-mindedness which they had found characterized prostitutes:

"The general moral insensibility, the boldness, egotism and vanity, the love of notoriety, the lack of shame or remorse. . .the desire for immediate pleasure without regard for consequences, the lack of forethought or anxiety about the future--all cardinal symptoms of feeble-mindedness--were strikingly evident."Thus the prostitute's failure to adhere to social conventions of behavior for women is here called feeble-mindedness.

The deliberate and even fraudulent misrepresentations of the people in the family studies have been established. Stephen Jay Gould, for example, has shown that H. H. Goddard, author of The Kallikak Family, retouched photographs to make the Kallikaks appear mentally retarded.

Family studies were used to support the myth of the "feeble-minded menace," which claimed the US was in imminent danger of being swamped by the degenerate and dangerous masses of the feeble-minded. When the feeble-minded menace was linked at the end of the 19th-century to the idea that the better stocks were failing to produce enough children, the idea of race suicide emerged. Race suicide captured the US imagination and lent support to the entire eugenics agenda.

The "race suicide" theory which developed during the first decade of the new century claimed that the greatly lowered birthrate of the better classes, coupled with the burgeoning birthrates of immigrants and the native-born poor, endangered the survival of "the race." "The race" was clearly a term that referred to the white, Anglo-Saxon race and a deep racism permeated the racial suicide period from its beginning in 1900 to 1910. One classic racial suicide work is Robert Reid Rentoul's

Race Culture; or, Race Suicide? (A Plea for the Unborn), published in New York and London in 1906. Rentoul speaks of the "terrible monstrosities" created by racial intermarriage and points out that the Americans are "poor patriots" for repealing their racial miscegenation statutes.

The concept of the feeble-minded menace provided a way to make the rural families, who were neither institutionalized, foreign, nor "colored," into people who were "different" from the eugenicists. Underlying the family studies and the myth of the feeble-minded menace was the theory of Social Darwinism, which assumed the existence of a struggle between the individual and society, and of an adversarial relationship between the fit and unfit classes. Eugenical family studies and social Darwinism both involved a transmutation of nature into biology and the eugenics movement frequently acknowledged its debt to Social Darwinism.

The deeply conservative implications of such philosophies included the rejection of government welfare programs or protective legislation on the grounds that such reforms as poorhouses, orphanages, bread lines, and eight-hour days enabled the unfit to survive and weakened society as a whole. From the beginning, the eugenics movement accepted the regressive implications of Social Darwinism. Karl Pearson believed that "such measures as the minimum wage, the eight-hour day, free medical advice, and reductions in infant mortality encouraged an increase in unemployables, degenerates, and physical and mental weaklings."

Pearson's friend, Havelock Ellis, known as a sex radical and free thinker, shared Pearson's elitist views, writing in his 1911 eugenicist book, The Problem of Race Regeneration, "These classes, with their tendency to weak-mindedness, their inborn laziness, lack of vitality, and unfitness for organized activity, contain the people who complain they are starving for want of work, though they will never perform any work that is given them." Ellis suggested in the same book that all public relief be denied to second generation paupers unless they "voluntarily consented" to be surgically sterilized.

One American eugenicist said harshly:

"The so-called charitable people who give to begging children and women with baskets have a vast sin to answer for. It is from them that this pauper element gets its consent to exist. . . .So-called charity joins public relief in producing stillborn children, raising prostitutes, and educating criminals."The economic conservatism of the movement was very clear. Faced with a social problem, the eugenicist leapt to the conclusion that it was the individual who must change to accommodate society (which is one reason why conservative commentators frequently argued that eugenics was a liberal movement committed to the supremacy of the community over the individual). The prevalence of the appeal to economics in eugenics writings led G. K. Chesterton to claim that the eugenicist was, at heart, the employer. Chesterton wrote:

"[N]o one seems able to imagine capitalist industrialism being sacrificed to any other object. . . .[the eugenicist] tacitly takes it for granted that the small wages and the income, desperately shared, are the fixed points, like day and night, the conditions of human life. Compared with them, marriage and maternity are luxuries, things to be modified to suit the wage-market."The eugenicists' family studies were one aspect of the movement's domestic program of scientific racism. The eugenics movement concentrated on differences: its roots in scientific racism looked to the differences between the white and other races, while the family studies created a distinction between fit and unfit white folks. At the same time, eugenicists and other scientific racists were discovering many different "races" among the foreign immigrants, all previously conceived as members of a single, "white" race.

The Eugenicist Role in Anti-Immigrant OrganizingThe involvement of the organized American eugenics movement with the advocacy of immigration restriction was deep and long-standing. Although the organized anti-immigrant movement predated eugenical organizations by a few years, immigration restriction was from the beginning a key component of the eugenics program. For example, the American Eugenics Society published a wide variety of materials on immigration restriction and the 1923 "Original Ultimate Program to be Developed by the American Eugenics Society" listed immigration restriction as one of the top three goals of the society.

The first organized anti-immigrant group, the Immigration Restriction League, was founded in 1894 in Boston by a small group of Harvard-educated lawyers and academics; Prescott Hall and Robert DeCourcey Ward were the driving forces behind the League. The Immigration Restriction League was based on a belief in the superiority of the white races. Ward summed up the group's philosophy when he wrote "the question [of immigration] is a race question, pure and simple. . . .It is fundamentally a question as to what kind of babies shall be born; it is a question as to what races shall dominate in this country."

Most eugenicists agreed, and Yale Professor and prominent eugenicist Irving Fisher's comment that "The core of the problem of immigration is. . .one of race and eugenics" was typical of the eugenicist position.

In the first decade of the century, the men of the Immigration Restriction League became active members of the Eugenics Section of the American Breeders' Association and other eugenics organizations, focusing their attention primarily on immigration issues. The connection was so compatible that the Immigration Restriction League almost changed its name to the Eugenic Immigration League. Hall and Ward even had sample stationery drawn up with the new name, but found the Board of Directors was unwilling to adopt the name of a movement younger than its own.

In 1918, Davenport and his fellow eugenicist, and virulent racist, and anti-immigration activist Madison Grant (author of The Passing of the Great Race and The Alien in Our Midst) set up the Galton Society. The Society was established for "the promotion of study of racial anthropology" and from the beginning, immigration restriction was "a subject of much interest."

As John Higham has noted, one strand of nativism in the US derived from a conviction that the immigrant was a political and social radical, importing communistic or anarchistic ideas into the United States. Grant and Davenport both shared this conviction and established the Galton Society in part to bar such foreign radicals. The independently wealthy Grant wrote to the other organizers, "My proposal is the organization of an anthropological society. . .confined to native Americans, who are anthropologically, socially, and politically sound, no Bolsheviki need apply."

Other prestigious members of the Galton Society included Henry Fairfield Osborn (who wrote the introduction to Grant's book) and Grant's friend and protégé, Lothrop Stoddard. Like his friend Grant, Stoddard was a strong anti-communist. His book The Rising Tide of Color argued that Bolshevism was a dangerous theory because it advocated universal equality rather than white supremacy.

H. H. Laughlin, of the Eugenics Research Association and Eugenics Record Office, was also very involved in anti-immigrant work. He produced many pamphlets on immigration, including "Biological Aspects of Immigration," "Analysis of America's Melting Pot," "Europe as an Emigrant-Exporting Continent," "The Eugenics Aspects of Deportation," and "American History in Terms of Human Migration." Because Laughlin had been appointed the Expert Eugenics Agent for the House Committee on Immigration and Naturalization by the committee's chair, Congressman Albert Johnson, many of these nativist pamphlets were published by the Government Printing Office in Washington, DC. In 1923, Johnson, a confirmed eugenicist, was appointed to the presidency of the Eugenics Research Association, a post held before him by Grant.

The immigration restrictionists were motivated by a desire to maintain both the white and the Christian dominance of the US. A year after the eugenicists' victory in securing passage of the 1924 Immigration Restriction Act, which established entry quotas that slashed the "new immigration" of Jews, Slavs, and southern Europeans, Davenport wrote to Grant, "Our ancestors drove Baptists from Massachusetts Bay into Rhode Island but we have no place to drive the Jews to. Also they burned the witches but it seems to be against the mores to burn any considerable part of our population. Meanwhile we have somewhat diminished the immigration of these people."

Similarly, the racial nature of the anti-immigration position was not veiled. In 1927, for instance, three years after the restrictive act of 1924 was passed, Grant, Robert DeCourcey Ward, and other eugenicists were still anxious to cut non-white immigration further. They signed a "Memorial on Immigration Quotas," urging the President and Congress to extend "the quota system to all countries of North and South America. . .in which the population is not predominantly of the white race."

The early 20th-century eugenics movement, often dismissed as a fad, provided a coherent and consistent political program to enforce the racial, class, and sexual dominance which was perceived to be under attack in American society. Its program has, in large part, reasserted itself in the late 20th-century, at a time when racial and economic elite dominance of US society is again under attack. The continuing vigor of scientific racism in the United States is in part a testimony to its strong, deep roots.