Zombie-Marxism Part 3.1: What Marx Got Wrong – Linear March of HistoryWhy Marxism Has Failed, and Why Zombie-Marxism Cannot Die

Or My Rocky Relationship with Grampa Karlby Alex Knight,

http://www.endofcapitalism.comPart 3.1 – September 19, 2011

This is part of an essay critiquing the philosophy of Karl Marx for its relevance to 21st century anti-capitalism. The main thrust of the essay is to encourage living common-sense radicalism, as opposed to the automatic reproduction of zombie ideas which have lost connection to current reality. Karl Marx was no prophet. But neither can we reject him. We have to go beyond him, and bring him with us. I believe it is only on such a basis, with a critical appraisal of Marx, that the Left can become ideologically relevant to today’s rapidly evolving political circumstances. [Click here for

Part 1and

Part 2.]

What Marx Got Wrong“Marxism has ceased to be applicable to our time not because it is too visionary or revolutionary, but because it is not visionary or revolutionary enough” – Murray Bookchin, “Listen, Marxist!”

Although Karl Marx provided us crucial and brilliant anti-capitalist critiques as explored in Part 2, he also contributed several key theoretical errors which continue to haunt the Left. Instead of mindlessly reproducing these dead ideas into contexts where they no longer make sense, we must expose the decay and separate it from the parts of Marx’s thought which are still alive and relevant.

I have narrowed down my objections to five core problems:

1. Linear March of History, 2. Europe as Liberator, 3. Mysticism of the Proletariat, 4. The State, and 5. A Secular Dogma.I submit that Marx’s foremost shortcoming was his theory of history as a linear progression of higher and higher stages of human society, culminating in the utopia of communism. According to Marx, this “progress” was manifest in the “development of productive forces,” or the ability of humans to remake the world in their own image. The danger of this idea is that it wrongly ascribes an “advance” to the growth of class society. In particular, capitalism is seen as a “necessary” precursor to socialism. This logic implicitly justifies not only the domination of nature by humanity, but the dominance of men over women, and the dominance of Europeans over people of other cultures.

Marx’s elevation of the “proletariat” as the agent of history also created a narrow vision for human emancipation, locating the terrain of liberation within the workplace, rather than outside of it. This, combined with a naive and problematic understanding of the State, only dispensed more theoretical fog that has clouded the thinking of revolutionary strategy for more than a century. Finally, by binding the hopes and dreams of the world into a deterministic formula of economic law, Marx inadvertently created the potential for tragic dogmatism and sectarianism, his followers fighting over who possessed the “correct” interpretation of historical forces.

(These mistakes have become especially apparent with hindsight, after Marxists have attempted to put these ideas into practice over the last 150 years. The goal here is not to fault Marx for failing to see the future, but rather to fault what he actually said, which was wrong in his own time, and is disastrous in ours. In this section I will limit my criticisms to Marx’s ideas only, and deal with the monstrous legacy of “actually existing” Marxism in Part 4.)

Capitalism is "advancing" us right off a cliff.

1. Linear March of History“Rooted in early industrialization and a teleological materialism that assumed progress towards communism was inevitable, traditional Marxist historiography grossly oversimplified real history into a series of linear steps and straightforward transitions, with more advanced stages inexorably supplanting more backward ones. Nowadays we know better. History is wildly contingent and unpredictable. Many alternate paths leave from the current moment, as they have from every previous moment too” – Chris Carlsson, Nowtopia (41).

Much of what is wrong in Marx stems from a deterministic conception of historical development, which imagines that the advance and concentration of economic power is necessarily progressive. According to this view, human liberation, which Marx calls communism, can only exist atop the immense productivity and industrial might of capitalism. All of human history, therefore, is nothing but “progressive epochs in the economic formation of society,” as Marx calls it in his Preface to

A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (1859):

“In broad outlines Asiatic, ancient, feudal, and modern bourgeois modes of production can be designated as progressive epochs in the economic formation of society. The bourgeois relations of production are the last antagonistic form of the social process of production… the productive forces developing in the womb of bourgeois society create the material conditions for the solution of that antagonism [communism].”The idea that history marches forwards along a linear path was not an original of Marx’s – as Bookchin writes in

The Ecology of Freedom, it stems from “Victorian prejudices” that “identify ‘progress’ with increasing control of external and internal nature. Historical development is cast within an image of an increasingly disciplined humanity that is extricating itself from a brutish, unruly, mute natural history” (272).

Marx absorbed this framework through Hegel, who theorized a pseudo-spiritual development of humanity towards the idealization of “Absolute Knowledge,” or God. The underlying logic of this divine movement is the attainment of higher levels of “Reason” – the human mind is increasingly able to detach itself from both the human body and from nature, and thereby exist “for itself.” In this way Hegel imagined that civilization had been evolving in a long dialectical process whereby humanity had become increasingly capable of conceptualizing freedom, and through events such as the French Revolution, was realizing that freedom in actuality.

Encoded in the word “teleology,” the linear march of history is a simplistic storyline whereby human history has a beginning, a middle, and an end. Along the way, the plot progresses and advances rationally through successive stages, inevitably reaching its predetermined destination. The famous “end of history” that Francis Fukuyama claimed had been achieved in 1989 with the downfall of the Soviet Union and the global dominance of Western capitalism was a distinctly Hegelian proposition. “Rational” capitalism had proven itself superior to “irrational” communism. The End.

Marx, like Fukuyama, inherited this Hegelian logic and succumbed to its tantalizing promise of unfolding destiny.1 However, Marx’s teleology was not concerned with the advance of philosophy or ideas, but was only meaningfully realized in the emancipation of humanity from class oppression. According to Marx, humanity becomes “for itself” through the advance of economic forces, which will free humans from “material want” and thereby eliminate the need for the division of society into rich and poor. Communism is forecast as the final stage of the storyline, when humanity will achieve its end in classlessness and material abundance. In his “Critique of Hegel’s Dialectic and General Philosophy” (1844), Marx explains this end:

“[Atheism and communism] are not an impoverished return to unnatural, primitive simplicity. They are rather the first real emergence, the genuine actualization, of man’s nature as something real” (Bottomore 213).

The core problem is Marx’s understanding of human liberation, which is posited as dependent on economic development. Instead of humanity possessing an innate and natural capacity for freedom, Marx delays “the first real emergence of man’s nature” to the end of history. Concerning himself with the “material conditions” for freedom, Marx fails to appreciate that people are constantly producing these conditions themselves in their own communities (taking care of one another, creating tools to accomplish work more efficiently, etc.), and that class systems like capitalism exist by leeching off those efforts, or impeding them to eliminate competition for institutionalized solutions. The development of massive industrialization and the emergence of powerful States do not bring with them the potential for liberation, but are that which humans must be liberated from.

This is not a question of technology, but of power. I fundamentally do not believe that liberation can be built on a foundation of oppression. Power must not be concentrated, but dispersed. Contrary to Marx, the imposition of class society does not enable progress, it obstructs progress.

Marx Against NatureMarx’s mistaken logic is repeatedly manifest in his ambivalent attitude towards capitalism. Not understanding capitalism’s constant need to perpetuate terrible violence against the planet, and as Silvia Federici adds (below), against women, Marx assigns a beneficial and essential role to capitalism in his grand storyline. Although terrible for its social injustice, the system is simultaneously hailed as a necessary “advance” by virtue of its unprecedented “development of productive forces.” In Capital, Vol. 3 (unpublished at his death), Marx argues:

“It is one of the civilizing aspects of capital that it enforces this surplus labour in a manner and under conditions which are more advantageous to the development of the productive forces, social relations, and the creation of the elements for a new and higher form than under the preceding forms of slavery, serfdom, etc.” (Marx-Engels Reader 440).

Today we know that capitalism threatens the very survival of the human species, and perhaps of the Earth itself. The billions of commodities pumped out by capital’s factories for rapid consumption and waste correspond directly to unprecedented damage to the world’s ecosystems. The clear-cutting of forests, the collapse of the ocean’s fisheries, the creation and spillage of toxic chemicals, the exhaustion of the fresh water supply, and the immense pollution of the atmosphere with greenhouse gases – with its corresponding destabilization of the climate – all call our attention to the ecological violence carried out by overdevelopment. Simply put, human economy is exploiting the world’s resources at a drastically unsustainable rate. In this context, any talk of capitalism today as a “higher stage” of development is simply ecocidal.

In Marx’s era, ecology as a science did not exist, and his comments on nature were few and far between. Obviously he could not have foreseen the predicament we are in today. However, there is a dangerous anti-ecological sentiment built into Marx’s linear march of history, which we reproduce at our own peril. It is not simply an academic question of “what Marx really believed.” If freedom is conceived of and built by extending capitalism’s “progress,” Marxists will (have and are) seek to further industrialize and “develop,” at the expense of the planet. Achieving a sustainable economy means not only breaking with capitalism for its mass production and industry, but breaking with a Marxist teleology that ignores humanity’s place in the larger web of life.

Opposing this view is an increasing push by some Marxists to discover an ecological wisdom in Marx. As I was writing this essay, I received an email by the Marxist magazine

The Monthly Review, telling me that a new book is coming out by John Bellamy Foster, author of numerous books on this subject, including

Marx’s Ecology. The aim of Foster’s writings, and others of the same thought, seems to be to locate any and all passages in Marx and Engels’ huge body of work that suggest at least an ambiguous or vaguely positive view of nature, then weave them together to create a picture of environmentalism. I find this endeavor unconvincing for several reasons – the comments cited by Foster and others are typically tangential to Marx’s main arguments and are often vague in content. On the contrary, Marx’s core argument about historical development is based on directly anti-ecological assumptions, which can only be explained away by performing intellectual gymnastics.

The key issue regards economic growth, or in Marx’s phrase, “the development of productive forces.” In “Wage Labour and Capital” (1847), Marx speaks of production as “action on nature,” revealing his awareness of the ecological basis for human economic activity (M-ER 207). However, rather than speaking of the need to transform economic activity so as to benefit humanity and nature together, Marx speaks simply in terms of quantity of production, to take as much as possible from the Earth. He repeatedly claims that what is needed is to develop the “modern means of production,” the industrial technology and centralization of capitalism.

“Only under [capital’s] rule does the proletariat… create the modern means of production, which become just so many means of its revolutionary emancipation. Only its rule tears up the material roots of feudal society and levels the ground on which alone a proletarian revolution is possible” (588, “The Class Struggles in France” 1850).

This celebration of the advance of industry reflects Marx’s belief that communism will be more capable of rapid industrialization than capitalism. Capitalism is expected to develop the “productive forces” too fast for its own good, leading to crises when production is “fettered” by the irrational organization of “bourgeois property.” From the “Communist Manifesto” (1848):

“The productive forces at the disposal of society no longer tend to further the development of the conditions of bourgeois property; on the contrary, they have become too powerful for these conditions, by which they are fettered, and so soon as they overcome these fetters, they bring disorder into the whole of bourgeois society… The conditions of bourgeois society are too narrow to comprise the wealth created by them” (478).

Communism is supposed to replace capitalism because its greater rationality will allow it to fully develop the means of production. Therefore, Marx’s historic mission for the proletariat is to seize control of the economy, not to slow down or decentralize industrialization; instead industrial growth is precisely the goal. The “Communist Manifesto” delivers one of Marx’s most important strategic statements:

“The proletariat will use its political supremacy to wrest, by degrees, all capital from the bourgeoisie, to centralise all instruments of production in the hands of the State, i.e., of the proletariat organised as the ruling class; and to increase the total of productive forces as rapidly as possible (emphasis added)” (490).

The key phrase “increase the total of productive forces as rapidly as possible” reveals much, but could be misinterpreted due to its vague character. Luckily, the same document fleshes this statement out a bit. Marx’s immediate goals for “the most advanced countries” (i.e. Europe) include, “Centralisation of the means of communication and transport in the hands of the State,” “Extension of factories and instruments of production owned by the State; the bringing into cultivation of waste-lands,” and “Establishment of industrial armies, especially for agriculture” (490).

The idea that industrialization will bring freedom is laid bare here. Apparently Marx was not aware of, or concerned with, the destruction industrial agriculture would inevitably reap on so-called “waste-lands,” which today we know as the marshes and flood-plains that sustain some of the most diverse ecosystems on land. Protecting precisely these areas from “development” has been one of the primary aims of environmentalism.

In

Capital, Vol. 3, Marx makes plain his “Victorian prejudices.” The purpose of developing industry “as rapidly as possible,” is for humanity to succeed in what he sees as its battle with a hostile Nature:

“Just as the savage must wrestle with Nature to satisfy his wants, to maintain and reproduce life, so must civilized man… Freedom in this field can only consist in socialized man, the associated producers, rationally regulating their interchange with Nature, bringing it under their common control, instead of being ruled by it as by the blind forces of Nature” (M-ER 441).2

Friedrich Engels, Marx’s lifelong friend and collaborator, was even more blunt on the matter. Engels’ 1880 pamphlet “Socialism: Utopian and Scientific” was one of the most important works for popularizing Marx’s theory. The pamphlet was published while Marx was still alive and even included an introduction by Marx, so it is very unlikely that Marx did not give his personal approval to its representation of the pair’s views. The essay explains the view that historical development is a process wherein humanity is liberated from Nature and comes to dominate it. It reaches a climax in this passage explaining the significance of “the seizing of the means of production” and the emergence of communism:

“[F]or the first time man, in a certain sense, is finally marked off from the rest of the animal kingdom, and emerges from mere animal conditions of existence into really human ones. The whole sphere of the conditions of life which environ man, and which have hitherto ruled man, now comes under the dominion and control of man, who for the first time becomes the real, conscious lord of Nature… It is the ascent of man from the kingdom of necessity to the kingdom of freedom” (Marx-Engels Reader 715-6).3

Marx and Engel’s communist utopia, to the extent that they elaborated it, is conceived as a highly developed industrial paradise, where machines produce massive outputs of goods and services with the least amount of labor. Standing atop this virtually unlimited material abundance, humans should theoretically have no reason for competition or division into classes. They will stop acting like “animals” and start behaving “rationally.”

Social peace is to be achieved through a cooperative war against nature. As Murray Bookchin summarizes, “In this dialectic of social development, according to Marx, man passes on from the domination of man by nature, to the domination of man by man, and finally to the domination of nature by man.”

Ecology is based on the fact that humans are just as much a part of the fabric of life as any other animal or life-form, and therefore the interests of humanity and nature are not in opposition, but the same. Marx and Engels’ “lord of Nature” statements are not exceptions to their overall theory of social development, but its inevitable end. A linear march of history, whereby “progress” is narrowly understood as stemming from economic growth,

cannot be compatible with an ecological perspective.

One may rise to the defense of Marx and Engels and point out the terrible social misery and poverty of 19th century Europe, which would justify the demand for economic growth. In fact, this echoes the thinking of much of the American Left today, living in the most affluent economy that has ever existed, but which still de-prioritizes ecology in favor of the short-sighted demand for investment to “create jobs.” The error of this logic is not that it calls attention to the need for economic resources, but that it places such need in opposition to the needs of the planet. Instead of downscaling and decentralizing the economy so that people can meet their material needs in an ecologically balanced way, capitalism is understood as “necessary” precisely for its immense centralized structures of production and distribution. Critiquing only the distribution and not the production, shallow Leftist politics seek to give more resources to the poor by exploiting the planet to a greater degree.

Now that industrialism threatens to destroy the Earth’s biosphere itself, the bankruptcy of this position should be obvious. One hundred and fifty years after Marx wrote his masterwork Capital, we can now see quite viscerally that capitalism is “advancing” us off a cliff.

Capitalism: A Historic SetbackMarx’s linear march of history not only leads to a dead end, it confuses its beginnings. Specifically, Marx fails to give full weight to the terribly violent origins of capitalism and ultimately justifies these horrors as necessary to reach a “higher stage” of development. However, as Silvia Federici points out, capitalism did not bring social progress with its emergence. On the contrary, it is better understood as a global system of abuse, which for the last 500 years has perpetuated itself through violence against the poor, women, people of color, rural communities, and the planet itself. In this view, “It is impossible to associate capitalism with any form of liberation” (Federici 17). Capitalism is better understood as a historic setback, from which we must recover not by “expropriating” it, but by abolishing it.

Marx does devote space in Capital (1867) to the brutal violence that created the landless European proletariat and launched the capitalist system into dominance over Europe. He refers to these violent beginnings as “primitive accumulation,” or the “historical process of divorcing the producer from the means of production” (Marx-Engels Reader 432). What this meant in lay-men’s terms was primarily the driving of Europe’s small farmers and peasants from their land and homes, and forcing people into the wage labor market. In contrast to the “bourgeois historians” who wash over these “enclosures” as merely a matter of “freeing” the workers from serfdom, Marx points out,

“[T]hese new freedmen became sellers of themselves only after they had been robbed of all their own means of production, and of all the guarantees of existence afforded by the old feudal arrangements. And the history of this, their expropriation, is written in the annals of mankind in letters of blood and fire” (433).

Only by eliminating the self-sufficient communities which made up Europe’s working class during the 14th and 15th centuries could capitalism take shape, because it is precisely the existence of a class of laborers who have nowhere to go and no way to provide for themselves asides from working for a wage that distinguishes capitalism from other systems of domination.

Marx also notes the “extirpation” of the American Indians, as well as the enslavement of millions of Africans, as necessary building blocks in the process of primitive accumulation for bringing immense wealth to the emerging European capitalist elite. He concludes: “capital comes [into the world] dripping from head to foot, from every pore, with blood and dirt” (435).

However, none of this shocking horror prompts Marx to rethink his linear march of history paradigm.

Capital, Vol. I ends with a weak and abstract justification for how displacement, slavery and genocide could be compatible with historical progress. For this, Marx returns to Hegel, and suggests that capitalism’s “expropriation” of the world’s population is only paving the way for is negation, communism:

“But capitalist production begets, with the inexorability of a law of Nature, its own negation. It is the negation of negation… the expropriators are expropriated” (438).

Discrediting these meaningless phrases, Silvia Federici – Italian autonomist and feminist – boldly asserts:

“Marx could never have presumed that capitalism paves the way to human liberation had he looked at its history from the viewpoint of women (emphasis added)” (12).

Federici has done a great service by making visible the hidden history of “primitive accumulation” through her book

Caliban and the Witch. The value of this book is not only that it fills in huge gaps in our knowledge of the origins and continuing bloody nature of capitalism; it also specifically illuminates the attacks on women, queer and trans people necessary for the creation and propagation of this social system.

Caliban and the Witch focuses on the long-ignored topic of the Great Witch Hunt. From the 15th to 17th centuries, being female in Europe was a risky proposition. If someone didn’t like you they could denounce you as a witch, and there was a real chance you would be rounded up by the authorities, accused of copulating with the devil, casting evil spells, consorting at Sabbats after dark, etc. You would most likely be tortured, then executed in the public square in front of relatives and children. Witch-hunting spanned both Catholic and Protestant nations, and the practice was carried out primarily at the hands of Church and State, not by the common person in the street.

The sheer scale and scope of this horror leads Federici to conclude that it was not accidental, but instead locates it as a key form of primitive accumulation:

“Hundreds of thousands of women were burned, hanged, and tortured in less than two centuries. It should have seemed significant that the witch-hunt occurred simultaneously with the colonization and extermination of the populations of the New World, the English enclosures, [and] the beginning of the slave trade” (164-5).

The identities of the women targeted by the witch hunts reveals much about the purpose of this campaign of murder. In most cases, their “crimes” were of a sexual or economic nature. The most common offenses were infanticide, abortion, inability or unwillingness to get pregnant, the sterility of a husband or other male, cheating on a spouse, sex of an “unproductive” nature (i.e. non-missionary), as well as theft, the death of livestock, or other misfortunes.

“[T]he witch was not only the midwife, the woman who avoided maternity, or the beggar who eked out a living by stealing some wood or butter from her neighbors. She was also the loose, promiscuous woman – the prostitute or adulteress, and generally, the woman who exercised her sexuality outside the bonds of marriage and procreation. Thus, in the witchcraft trials, ‘ill repute’ was evidence of guilt. The witch was also the rebel woman who talked back, argued, swore, and did not cry under torture” (184).

In short, the witch hunt was primarily a war against female sexuality and female economic independence. Whereas before capitalism, many European women had enough independence to support themselves as healers, midwives, herbalists, gardeners, prostitutes, fortune tellers, etc., the witch hunts eliminated most of these opportunities. By the 17th century most European women had become restricted to the roles of housewife and mother (24-5). As this work of taking care of men and children, which Federici calls “reproductive labor,” was unpaid, while males could hold waged jobs and earn an income, a “new sexual division of labor” was constructed whereby women became dependent on men for economic survival (170).

Another hidden aspect of this history is that the witch hunt also targeted homosexuality and gender non-conformity. Silvia Federici reminds us that among the “unproductive sex” demonized during this time was any sex other than that between one male and one female. Across much of Europe up to that point, homosexuality had been accepted and even celebrated. In the town of Florence, for example, Federici asserts,

“[H]omosexuality was an important part of the social fabric ‘attracting males of all ages, matrimonial conditions and social rank.’ So popular was homosexuality in Florence that prostitutes used to wear male clothes to attract their customers” (58-9).

In the new patriarchal order of capitalist Europe, which was obsessed with controlling reproduction, non-conformity of gender or sexuality were seen as threats to monogamous marriage. An unknown number of queer and trans people lost their lives in the witch burnings, but Federici points out that the word “faggot” remains in our language as a reminder of the terror that converted human beings into kindling for the flame (197).

Silvia Federici’s argument is not that feudalism was a wonderful or idyllic system either – it was still a class society. Instead, she points to the enormous peasant movements and heretical movements active in Europe during the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries as indications that in the breakdown of the feudal system, other worlds were possible. In place of Marx’s deterministic formula for “progressive epochs in the economic formation of society,” we can understand that human beings make their own history, either by submitting to systems of oppression and authority, or by working together for collective liberation. There is a constant struggle between those in power and those against it, and the future can go in any direction as that struggle shifts, moves, and evolves.

In this light, Federici argues the “transition” from feudalism to capitalism was not an “evolutionary development” of economic forces, but rather a brutal “counter-revolution” carried out by the old feudal elites and emerging merchant class (21).4 Most of the Crusades, as well as the Inquisition, were levied against Europe’s internal enemies: the poor and working classes. The goal of the repression was to stop the social revolution that was spreading out of control, and spilling over into “national liberation” struggles such as the Peasant’s War of Germany or the Hussite rebellion in what is now the Czech Republic. Recovering the hidden history of these epic clashes embarrasses the view of capitalism as an “advance,” showing that it has only “advanced” over hundreds of thousands of dead peasants and proletarians, destroying their rebellious attempts to create a non-feudal, non-capitalist world.

In the face of this bloody history, it seems no longer morally acceptable to justify the violence of “primitive accumulation” as necessary for historical development. Capitalism did not move us forwards, but backwards. Federici concludes that the creation of capitalism not only reduced human beings to landless proletarians, but introduced new sexual, gender, and racial hierarchies to divide the working class and make revolution significantly more difficult.

“[Primitive accumulation] required the transformation of the body into a work-machine, and the subjugation of women to the reproduction of the work-force. Most of all, it required the destruction of the power of women which, in Europe as in America, was achieved through the extermination of the ‘witches.’ Primitive accumulation, then, was not simply an accumulation and concentration of exploitable workers and capital. It was also an accumulation of differences and divisions within the working class, whereby hierarchies built upon gender, as well as ‘race’ and age, became constitutive of class rule and the formation of the modern proletariat. We cannot, therefore, identify capitalist accumulation with the liberation of the worker, female or male, as many Marxists (among others) have done, or see the advent of capitalism as a moment of historical progress. On the contrary, capitalism has created more brutal and insidious forms of enslavement, as it has planted into the body of the proletariat deep divisions that have served to intensify and conceal exploitation. It is in great part because of these imposed divisions – especially those between women and men – that capitalist accumulation continues to devastate life in every corner of the planet” (63-4).

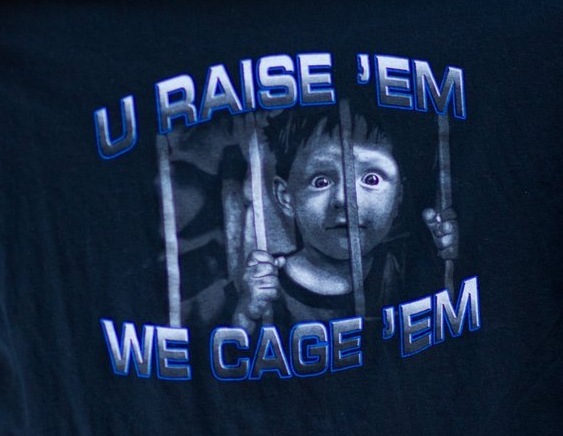

Women, queer and trans people, and other oppressed groups in the Global North have all made tremendous strides towards equality and recognition in recent decades. However, Silvia Federici reminds us that “primitive accumulation” did not just launch capitalism, it has accompanied the spread of capitalist relations across the world. At the same time that Northern society has opened up for women and minorities, capitalism has exported more vicious patriarchal violence to much of the Global South, devastating the social fabric. Today we can see it most horrifically in the mass rapes, child slavery and ethnic cleansing of the Congo, where various factions and government armies fight over access to minerals like

coltan. The global market for minerals used in laptops, video games and cell phones relies on the cheapening of these resources, and also the cheapening of African lives. With arms money pouring in, some five million Congolese have died in the last eight years. The despair of the Congolese is not natural – it is being manufactured through brutal capitalist enclosures on their self-sufficient ways of life.

In order to uphold Marx’s linear march of history, we would have to ignore, deny, or rationalize these realities of social and ecological trauma. By shelving all “pre-capitalist” cultures as “lower” forms of social development, Marx unfortunately justified the violent imposition of capitalism on his European ancestors (and the rest of the world as I will explain in the next section). As Silvia Federici makes visible, this campaign was directed especially against women, homosexuals and gender non-conformists through the witch hunts. While Marx himself was apparently unaware of the sexual nature of “primitive accumulation,” such ignorance is much harder to justify in our current age of global information.

Postmodernism was largely a response to the failure of Marx’s deterministic narrative. It argued that there is no one single narrative – a thousand ways of understanding the same events are all valid. We don’t have to follow this backlash to its extreme and declare, as some do, that big-picture narratives as such are oppressive. Instead, critiquing the linear Marxist narrative provides an opportunity to generate a more liberating narrative of human history.

A liberating narrative would be one that sees, for example, the autonomous nature of human freedom, being something that people create in their own communities, on an egalitarian basis, in communion with nature and not against it. Class, the State, patriarchy, and all oppressive systems would have to be cast aside as fundamentally destructive, and the impossibility of achieving liberation through the advancement of these forces should be clearly stated. The fortunes of the movement(s) for human emancipation would be understood to go through ups and downs, and although the capitalist epoch has been the most destructive towards humanity and the planet, its end opens up a wide range of possibilities for alternative systems of production and reproduction. As Chris Carlsson pointed out in the quote at the start of this section, there is no single path to liberation, and we cannot demand the entire world follow one.

Because capitalism’s continued assault on the world has proven Marx’s linear march of history untenable, many clear-thinking Marxists have abandoned this theory and are specifically incorporating ecological and feminist wisdom into their politics of class struggle. However, undead notions of “progress” and “development” remain in the muddled thinking of many, reproducing outdated and destructive politics which continue to damage the relevance and moral character of the Left.

In 2010, certainly the worst case of such developmentalist logic shuffles along in the Chinese Communist Party, which in Marx’s name is turning China into a mega-producing and mega-consuming industrial capitalist powerhouse – with dire consequences for the ecosystems of China and the planet as a whole. China is now the second-largest consumer of oil in the world behind the United States, and at Copenhagen last year allied with the U.S. to sabotage a meaningful climate agreement. Now as the Cancun climate talks approach, China’s Zombie-Marxism will likely continue to play a disastrous role, preventing the world leaders from seriously tackling global warming.

Footnotes

1. Engels summarized the value he and Marx found in Hegel’s “gradual march” of history in his 1880 pamphlet, “Socialism: Utopian and Scientific”:“In [the Hegelian] system – and herein is its great merit – for the first time the whole world, natural, historical, intellectual, is represented as a process, i.e., as in constant motion, change, transformation, development; and the attempt is made to trace out the internal connection that makes a continuous whole of all this movement and development. From this point of view the history of mankind no longer appeared as a wild whirl of senseless deeds of violence, all equally condemnable at the judgement-seat of mature philosophical reason and which are best forgotten as quickly as possible, but as the process of evolution of man himself. It was now the task of the intellect to follow the gradual march of this process through all its devious ways, and to trace out the inner law running through all its apparently accidental phenomena” (M-ER 697).

2. This domination of nature theme was expounded further in an article Marx wrote for the New York Tribune in 1853: “The bourgeois period of history has to create the material basis of the new world [including] the development of the productive powers of man and the transformation of material production into a scientific domination of natural agencies (emphasis added). Bourgeois industry and commerce create these material conditions of a new world in the same way as geological revolutions have created the surface of the earth. When a great social revolution shall have mastered the results of the bourgeois epoch, the market of the world and the modern powers of production, and subjected them to the common control of the most advanced peoples, then only will human progress cease to resemble that hideous, pagan idol, who would not drink the nectar but from the skulls of the slain.”

3. Engels goes further when he writes, “[If] division into classes has a certain historical justification, it has this only for a given period, only under given social conditions. It was based upon the insufficiency of production. It will be swept away by the complete development of modern productive forces… The expansive force of the means of production bursts the bonds that the capitalist mode of production had imposed upon them. Their deliverance from these bonds is the one precondition for an unbroken, constantly accelerated development of the productive forces, and therewith for a practically unlimited increase of production itself (emphasis added)” (M-ER 714-5).

4. Here is Federici’s full quote: “Only if we evoke these struggles [of the European medieval proletariat], with their rich cargo of demands, social and political aspirations, and antagonistic practices, can we understand the role that women had in the crisis of feudalism, and why their power had to be destroyed for capitalism to develop, as it was by the three-century-long persecution of the witches. From the vantage point of this struggle, we can also see that capitalism was not the product of an evolutionary development bringing forth economic forces that were maturing in the womb of the older order. Capitalism was the response of the feudal lords, the patrician merchants, the bishops and popes, to a centuries-long social conflict that, in the end, shook their power, and truly gave ‘all the world a jolt.’ Capitalism was the counter-revolution that destroyed the possibilities that had emerged from the anti-feudal struggle – possibilities which, if realized, might have spared us the immense destruction of lives and the environment that has marked the advance of capitalist relations worldwide. This much must be stressed, for the belief that capitalism ‘evolved’ from feudalism and represents a higher form of social life has not yet been dispelled” (Federici 21-22).