.

GET right up close to Dmitry Itskov and sniff all you like — you will not pick up even the faintest hint of crazy. He is soft-spoken and a bit shy, but expansive once he gets talking, and endearingly mild-mannered. He never seems ruffled, no matter what question you ask. Even if you ask the obvious one, which he has encountered more than a few times since 2011, when he started “this project,” as he sometimes calls it.

Namely: Are you insane?

“I hear that often,” he said with a smile, over lunch one recent afternoon in Manhattan. “There are quotes from people like Arthur C. Clarke and Gandhi saying that when people come up with new ideas they’re called ‘nuts.’ Then everybody starts believing in the idea and nobody can remember a time when it seemed strange.”

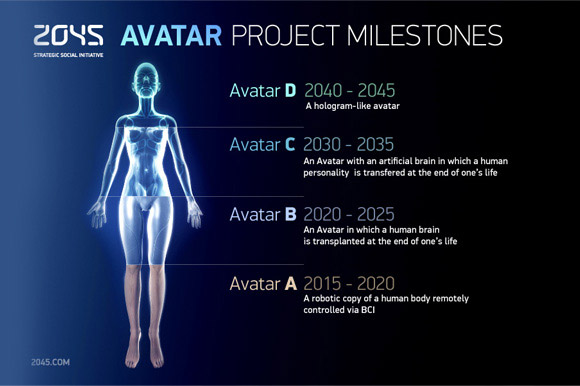

It is hard to imagine a day when the ideas championed by Mr. Itskov, 32, a Russian multimillionaire and former online media magnate, will not seem strange, or at least far-fetched and unfeasible. His project, called the 2045 Initiative, for the year he hopes it is completed, envisions the mass production of lifelike, low-cost avatars that can be uploaded with the contents of a human brain, complete with all the particulars of consciousness and personality.

What Mr. Itskov is striving for makes wearable computers, like Google Glass, seem as about as futuristic as Lincoln Logs. This would be a digital copy of your mind in a nonbiological carrier, a version of a fully sentient person that could live for hundreds or thousands of years. Or longer. Mr. Itskov unabashedly drops the word “immortality” into conversation.

Yes, we have seen this movie and, yes, it always leads to evil robots enslaving humanity, the Earth reduced to smoldering ruins. And it’s quite possible that Mr. Itskov’s plans, in the fullness of time, will prove to be nothing more than sci-fi bunk.

But he has the attention, and in some cases the avid support, of august figures at Harvard, M.I.T. and Berkeley and leaders in fields like molecular genetics, neuroprosthetics and other realms that you’ve probably never heard of. Roughly 30 speakers from these and other disciplines will appear at the second annual 2045 Global Future Congress on June 15 and 16 at Alice Tully Hall, in Lincoln Center in Manhattan.

Though billed as a congress, the event is more like a showcase and conference that is open to the public, with general admission tickets starting at $750. (About 400 tickets, roughly half the total available, have been sold so far.) Attendees will hear people like Sir Roger Penrose, an emeritus professor of mathematical physics at Oxford, who appears on the 2045.com Web site with a video teaser about “the quantum nature of consciousness,” and George M. Church, a genetics professor at Harvard Medical School, whose video on the site concerns “brain healthspan extension.”

As these videos suggest, scientists are taking tiny, incremental steps toward melding humans and machine all the time. Ray Kurzweil, the futurist and now Google’s director of engineering, argued in “The Singularity Is Near,” a 2005 book, that technology is advancing exponentially and that “human life will be irreversibly transformed” to the point that there will be no difference between “human and machine or between physical and virtual reality.”

Mr. Kurzweil was projecting based on the scientific and intellectual ferment of the time. And technological achievements have continued their march since he wrote the book — from creating computers that can that can outplay humans (like Watson, the “Jeopardy” winner from I.B.M.) to technology that tracks a game player’s heartbeat and perhaps his excitement (like the new Kinect) to digital tools for those with disabilities (like brain implants that can help quadriplegics move robotic arms).

But most researchers do not aspire to upload our minds to cyborgs; even in this crowd, the concept is a little out there. Academics seem to regard Mr. Itskov as sincere and well-intentioned, and if he wants play global cheerleader for fields that generally toil in obscurity, fine. Ask participants in the 2045 conference if Mr. Itskov’s dreams could ultimately be realized and you’ll hear everything from lukewarm versions of “maybe” to flat-out enthusiasm.

“I have a rule against saying something is impossible unless it violates laws of physics,” Professor Church says, adding about Mr. Itskov: “I just think that there’s a lot of dots that aren’t connected in his plans. It’s not a real road map.”

Martine A. Rothblatt, another speaker at the coming conference and founder of United Therapeutics, a biotech company that makes cardiovascular products, sounds more optimistic.

“This is no more wild than in the early ‘60s, when we saw the advent of liver and kidney transplants,” Ms. Rothblatt says. “People said at the time, ‘This is totally crazy.’ Now, about 400 people have organs transplanted every day.”

At a minimum, she and others believe that interest in building Itskovian avatars will give birth to and propel legions of start-ups. Some of these far-flung projects have caught the eyes of angel investors, and one day these enterprises may do for the brain and androids what Silicon Valley did for the Internet and computers.

Mr. Itskov says he will invest at least part of his fortune in such ventures, but his primary goal with 2045 is not to become richer. In fact, the more you know about Mr. Itskov, the less he seems like a businessman and the more he seems like the world’s most ambitious utopian. He maintains that his avatars would not just end world hunger — because a machine needs maintenance but not food — but that they would also usher in a more peaceful and spiritual age, when people could stop worrying about the petty anxieties of day-to-day living.

“We need to show that we’re actually here to save lives,” he said. “To help the disabled, to cure diseases, to create technology that will allow us in the future to answer some existential questions. Like what is the brain, what is life, what is consciousness and, finally, what is the universe?”

MR. ITSKOV’S role in the 2045 Initiative is bit like that of a producer in the Hollywood sense of the word: the guy who helps underwrite the production, shapes the script and oversees publicity. He says he will have spent roughly $3 million of his own money by the time the second congress is over, and though he is reluctant to disclose his net worth — aside from scoffing at the often-published notion that he’s a billionaire — he is ready to spend much more.

For now, he is buying a lot of plane tickets. He flies around the globe introducing himself to scientists, introducing scientists to one another and prepping the public for what he regards as the inevitable age of avatars. In the span of two weeks, his schedule took him from New York (for an interview), to India (to enlist the support of a renowned yogi), home to Moscow, then to Berkeley, Calif. (to meet with scientists), back to Moscow and then to Shanghai (to meet with a potential investor).

When he isn’t pushing his initiative, he leads a life that could best be described as monastic. He meditates and occasionally spends days in silent retreat in the Russian countryside. He is single and childless, and he asked to keep mention of his personal life to a minimum, for fear that he would come across either as an oddball or an ascetic boasting about his powers of restraint.

“In some ways, I’m a monk,” he said. “Not entirely. Some monks struggle to stay monks. But I’m happiest when I live like a monk.”

Maybe it’s all his talk of androids, but Mr. Itskov has the kind of generically handsome face and perfect smile that seem computer-generated. He speaks English with a slight accent and wears Borelli blazers and an Audemars Piguet watch made of rose gold, both of which seem like extravagances to him now. Rubles that aren’t plowed into the initiative are, to him, a waste.

“I used to have a collection of watches,” he says, grinning at how inane that now seems. “I gave most of them away, and I’m never buying anything like that again.”

A few weeks ago, Mr. Itskov, wearing a Borelli blazer, traveled to the University of California, Berkeley, where a group of researchers and professors gave him a tour of their labs. The main point of his visit was to discuss a brain-related project that is now under wraps. That happened at a private dinner, and Mr. Itskov politely declined to say anything about it. But during the day, it was basically show-and-tell time for brain-tech fanboys, and it started at the Berkeley Wireless Research Center. The center is sponsored by Intel, Samsung and other companies eager for a first look at whatever is being conceived there. The day ended on the other side of the campus, at the Swarm Lab, which is subsidized by Qualcomm.

At the Swarm Lab, Peter Ledochowitsch, a researcher with a thick red beard, described a minimally invasive brain implant designed to read intentions from the surface of the brain. So far, the device has been implanted in an anesthetized rat; a prototype for alert animals is in the works. But eventually, he said, it would allow paralyzed people to communicate, or to control a robotic arm or a wheelchair. It could also allow you to start your car if you think, “Start my car.”

Like other researchers on campus, Mr. Ledochowitsch has founded a company — his is called Cortera Neurotechnologies — that he hopes will eventually mass-produce and market this device. He has no expectation that Mr. Itskov will be an angel investor in the business, but angel investor money is what he will seek.

“We’ve talked to a number of venture capitalists,” he said. “The problem is that they’re spoiled by Silicon Valley, where six guys can turn around some stupid social networking software in six months. If your timeline is 2021, it makes them very nervous.”

MR. ITSKOV’S timeline is even further out, but he is still eager for progress. He was mostly silent during the tour of the Berkeley labs, aside from asking variations on the theme of, “When will this be ready?” He could have discussed Berkeley’s secret project over the phone, rather than flying from Moscow for a dinner, but he relishes visiting any place that could produce breakthroughs in cybernetic immortality.

“It’s good to see the atmosphere,” he said the next day over lunch at a restaurant in Berkeley. “I want my project to be international, a huge collaboration of different scientists. It’s worth meeting, in person, everyone who is in this field.”

Mr. Itskov has apparently never done anything halfway. He was raised in Bryansk, a city about 230 miles southwest of Moscow, with a father who directed musical theater and a mother who was a schoolteacher. The father, Ilya Itskov, said through an interpreter in a phone interview that his son was a perfectionist who would not stop trying to learn a subject — be it a foreign language or windsurfing — until he’d mastered it.

“From the very beginning,” he said, “we realized that Dmitry is not an ordinary person.”

He attended the Plekhanov Russian Academy of Economics, where he met his future business partner, Konstantin Rykov. In 1998, Mr. Rykov started an e-zine with an English-language obscenity for a name, which was loaded with jokes about culture, showbiz and relationships.

Mr. Itskov came on board the next year, and the two began branding their collaborations as Goodoo Media. The company built tarakan.ru, a blog about the Russian Internet, and an online newspaper, Dni.ru, a tabloidy take on sports, politics and entertainment. Online game sites and other online newspapers would follow, along with a glossy print magazine, a book publisher and Internet TV channel. A media empire was born. In “The Net Delusion,” Evgeny Morozov, an expert on the tangle of Russian politics and the Web, writes that Mr. Rykov became “an undisputed Godfather of the Russian Internet.”

The sites earned money through ads, Mr. Itskov says, but the company, renamed New Media Stars, also came to have very highly placed allies. At some point, Mr. Rykov segued from counterculture bad boy to friend of the Kremlin. Mr. Morozov writes that the company and its media empire have churned out “heaps of highly propagandistic video content” for the United Russia party of President Vladimir V. Putin. One of the company’s sites was called zaputina.ru, which translates to “For Putin!”

Mr. Rykov declined a request for an interview. Mr. Itskov, whose principal roles were business development and managing New Media’s roughly 250 employees, says the company never received money from the United Russia party. He has never met Mr. Putin, he adds, though he voted for him. “In Russia, the majority of people love him,” he said.

Mr. Itskov was helping to build New Media Stars when he had an uncomfortable epiphany. It was 2005, and he was staring at his computer screen at the company’s offices, then housed on a barge on the Moscow River. In an instant, he knew that a life spent accumulating money would not suffice.

“At the time, we’d had a very interesting proposal to sell some shares of the company,” he recalls, “and I realized, given what the offer meant for the valuation of the company, that I could live very well. And then I realized that I wouldn’t be happy, just working and spending money. I would just age and then die. I thought there should be something deeper.”

At the age of 25, he started to have the symptoms of a midlife crisis. He anticipated the regrets he might have as an old man — the musical instruments unlearned, the books unread. The standard span of 80 or so years suddenly seemed woefully inadequate. He soon was seeking out leaders from almost every religion, in a search for purpose and peace.

The more he contemplated the world, the more broken it seemed.

“Look at this,” he said, opening his laptop on the table and starting a slide show with one heartbreaking statistic after another: Almost one billion people are now starving. Forty-nine countries are currently involved in military conflict. Ten percent of people are disabled. And so on.

“That is the picture of this world that we created, with the minds we have today, with our set of values, with our egotism, our selfishness, our aggression,” he went on. “Most of the world is suffering. What we’re doing here does not look like the behavior of grown-ups. We’re killing the planet and killing ourselves.”

TO change that picture, he reasons, we must change our minds, or give them a chance to “evolve,” to use one of his favorite words. Before our minds can evolve, though, we need a new paradigm of what it means to be human. That requires a transition to a world where most people aren’t consumed by the basic questions of survival.

Hence, avatars. They may sound like an improbable way to solve the real problems on Mr. Itskov’s laptop, or like the perfect gift for the superrich of the future. But the laws of supply and demand abide in Mr. Itskov’s utopia, and he assumes that once production of avatars is ramped up, costs will plunge. He also assumes that charities now devoted to feeding, clothing and healing the poor will focus on the goal of making and distributing affordable bodies, which in this case means machines.

For now, just acquiring a lifelike robotic head is a splurge. Among the highlights of the congress at Lincoln Center will be the unveiling of what Mr. Itskov describes as the most sophisticated mechanical head in history. It is a replica of Mr. Itskov from the neck up, and it is now under construction in Plano, Tex., home of Hanson Robotics, a company founded by David Hanson, who has a doctorate in interactive arts and engineering and who has previously fabricated robotic heads for research labs around the world. (Mr. Itskov said Mr. Hanson would not allow him to discuss price.)

“Most robotic heads have 20 motors,” Mr. Hanson said in a phone interview. “Mine have 32. This one will have 36. So, more facial expressions, simulating all the major muscle groups. We’ve had four people working on this full time since March.”

The even more remarkable expectation is that while Mr. Itskov is in another room, sitting before a screen with sensors to pick up his every movement, the head will be able to reproduce his expressions and voice. “He’s controlling that robot, controlling its gestures, its expression and its speaking with his voice in real time,” Mr. Hanson says. “It’s somewhere between a cellphone call and teleportation.”

MR. ITSKOV’S initiative is nothing if not forward-looking, but he sees it as a present-day end in itself.

“The whole problem with humanity is that we don’t currently plan for the future,” he said. “Our leaders are focused on stability. We don’t have something which will unite the whole of humanity. The initiative will inspire people. It’s about changing the whole picture, and it’s not just a science-fiction book. It’s a strategy already being developed by scientists.”

It’s also been dramatized by Hollywood. Mr. Itskov is a fan of “Avatar” and other films in the sci-fi genre, like “Surrogates,” a Bruce Willis vehicle about a world where people can interact with society through remotely controlled humanoid robots.

“Surrogates,” like so many films of its kind, contains plenty of terrifying, brink-of-extinction plot twists. And Mr. Itskov is well aware that few visions of a techo-Edenic future end well. That is one reason he recruits spiritual figures to his cause, with the idea that a project with such immense ramifications needs buy-in from various faiths and, more important, input about ethics.

Just because religious leaders will appear at the congress doesn’t make them eager boosters. One of the speakers is Lazar Puhalo, a retired archbishop of the Orthodox Church in America, who has also studied physics and neurobiology. In recent telephone interview, he said avatars of some kind would almost certainly be part of our future, a notion that fills him with considerable dread.

“The creators of this ‘something else’ will have their own fears and prejudices,” he says, “and you could produce those robotically. Which could be a real horror for humanity.”

His goal in attending the Congress is to stand up for human beings, which he sees as interesting precisely because of their shortcomings and foibles. And he’d like to make the point that immortality sounds like a ghastly idea.

“Life would get deathly boring,” he says. “It’s like talking to couples that want to divorce. The hormones have quieted down. You don’t feel butterflies. The longer you’re around, the duller it gets.”

Do people want to live forever? If yes, would they like to spend that eternity in a “nonbiological carrier”? What happens to your brain once it’s uploaded? What about your body? If you could choose when to acquire an avatar body, what’s the ideal age to acquire it? Can avatars have sex?

These are just a few of the dozens of questions raised by the 2045 Initiative. (Yes, avatars can have sex, Mr. Itskov writes in an e-mail, because “an artificial body can be designed to receive any sensations.”) One point of the coming congress is to address such issues.

But a larger question hovers above all others: Should Mr. Itskov be taken seriously? Much about his initiative sounds preposterous. On the other hand, many of those conversant in the esoteric disciplines that would produce an avatar are huge fans.

So one can imagine two radically different legacies for this singular man. If he succeeds, history will remember Mr. Itskov as a daring visionary whose money and energy redefined life in ways that solved some of the world’s most intransigent problems. If he fails, the word “cockamamie” is sure to show up somewhere in his obituary.

COMMENTS:

NotJc

Controlled immortality is the way of the future, looking forward to a never ending life is pointless, there will be no more space on this ever shrinking paradise we call home

June 2, 2013 at 11:47 p.m.RECOMMENDED2

nomanCA

No one who has him/herself replicated in software/hardware will be 'immortal' - what happens to your computer after 10 years? Who will maintain 'you'? What about hacking!??that'd be rich.

June 2, 2013 at 11:47 p.m.RECOMMENDED2

Michael O'NeillBandon, Oregon

This 'immortality' is no different than the shadow of Xenophon contained in the annuls of the Anabasis. Men and women have been transferring their thoughts and emotions to mechanical contrivance for millennia.

The serendipity of Mr. Itzkov's industry will no doubt be welcomed by artificial organ recipients everywhere. But any simulacrum created will be no more a continuation of the life of this quixotic millionaire than will his tombstone.

Is it not strange what fear of death will bring a man to do?

JJEMSan Sebastian, Spain

Just from the "mechanical" aspect, it would certainly be quite difficult to "copy" the content of the brain based on the binary technology of today's computers, but how so when we master quantum technology not too far from now?

June 2, 2013 at 11:47 p.m.RECOMMENDED1

HPDallas, TX

I have watched and read futurists for enough time and I deeply mistrust them. They are peddlers of lies just like many ancient prophets, selling prophecies that cannot be verified until it is too late.

I hate Ray Kurzweil's grandiose claims. It's sickening and it smacks of peddling. It's one thing to say that we have these and these results and the next logical step is this. It's dishonest to say that a computer program that can play chess better than any human implies that artificial intelligence is at hand. All it takes is brute-force evaluation of the several possible moves available and then picking the best one. It's easy to implement that process on a computer. How on earth the brain does the whole thing is still not understood. Parts maybe, but the whole? No. The challenge here is nothing less than the complete replication of mental processes and attendant support systems.

There will be some scientists with good ideas and I hope they get the funding they are obviously trying to get, but I know that it's usually the charlatans who talk the loudest, and the good scientist are cautious. So I don't have much hope for the `congress'.

On a separate note, all this money and effort to make an avatar is better spent on providing food and shelter, especially if the plan is to start producing ten billion avatars in 2045. Oh no, but we probably have limited resources, so guess what, you guys will still have to compete, just like the old days in 2013.

June 2, 2013 at 8:31 p.m.RECOMMENDED4

chrisUSA

1) One thing that seems to not be discussed very much is how the exponentially increasing advancements of technology put more and more power to transform human civilization into fewer and fewer people's hands. Along with the capitalism that is investing and allowing such projects to condense, at what point will most of human kind who are not multi-millionaire technologist feel that we have become completely subordinate to technological systems (and their wealthy inventors/investors) which we have no control over?

2) Hand in hand with the risks of this concentration of technological power in the hands of the few is the somewhat obvious fact that when a whole civilization can be transformed in ever decreasing amounts of time (in both positive and negative ways) one single well-intentioned invention might turn out to have effects that, from many people's perspectives, are extremely negative. At the very least, consider the atom and hydrogen bombs. But when human life is interconnected in the extreme, ever reliant on other people's inventions/maintenance that are not found in nature, the risks of catastrophe would seem very real.

To assume that humans will be capable of protecting humanity or the planet from the technology they produce simply isn't backed up by the evidence of history.

June 2, 2013 at 8:30 p.m.RECOMMENDED2

RobBurlington, VT

This whole enterprise makes many assumptions about the nature of consciousness, i.e., that it is a "thing" which is based on a brain, and that a brain is nothing more than circuitry which will one day be mimicked by a machine. Mr. Istkov should be very careful about the yogis he is seeking out to sanction his project; should he find the "wrong" one, he will learn that the very "I" which he seeks to propagate indefinitely does not in fact have any material existence whatsoever.

June 2, 2013 at 8:30 p.m.RECOMMENDED1

KaceeHawaii

How does the mind then progress, as in revising thoughts and experiences?

June 2, 2013 at 8:30 p.m.RECOMMENDED1

RonnieSanta Cruz, CA

Somehow, these people seem to forget that the computer systems into which avatars will be, presumably, uploaded will still require material computers and electricity to operate (see story about energy intensive server farms). I suppose robots could maintain the hardware, and there would be robots to maintain the repair robots, ad infinitum (like little fleas on fleas, and littler fleas on the little ones). But stop me if you've heard this one before.

June 2, 2013 at 5:31 p.m.RECOMMENDED2

dadsterLondon

there are alternate energy sources like Solar energy and bio-energy wind energy, energy from gravity, oceans , heat from earth's core etc to Electric batteries . In fact energy will no more be a problem by 2045. That's exactly what makes all this technology possible !

June 2, 2013 at 8:30 p.m.

ericcalifornia

Finding the answer to "What is conciousness? might be on the same level as determining WHY 2 hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom put together in a particular way BECOME water. What really is emergence? Until we answer this completely it seems we will not be able take our minds and place them into machines.

June 2, 2013 at 5:31 p.m.RECOMMENDED2

YodaDC

should not this article be under the "science fiction" section of the NY Times instead of the "business" section?

June 2, 2013 at 5:31 p.m.

Red State GalMaryland

He "will focus on the goal of making and distributing affordable bodies, which in this case means machines." Wouldn't it be far better to use his resources to make our own bodies "affordable"? Wouldn't that be a far more humane course? (Something like making photosynthesis possible for humans, for example?)

Also, I think we overlook how much our consciousness is shaped by our corporeality. To lose direct sensation of our body would be like receiving a lobotomy of sorts. This will not enhance our consciousness; it can only diminish it.

All in all, I can see how this is the product of an unattached man with no children.

June 2, 2013 at 5:31 p.m.

SamirSan Luis Obispo, CA

The great sage Ramana Maharshi used to tell visitors to his ashram that the only question they needed to answer was "Who am I?"

The answer lies beyond personality, particularity, circumstance, gender - beyond all that Dmitry Itskov may be able to transfer to his planned simulacrum.

Perhaps Mr. Itskov should first ask himself this seemingly simple question: Who am I?

June 2, 2013 at 5:31 p.m.

KaceeHawaii

A simple product of evolution.

June 2, 2013 at 8:30 p.m.

sautererPell City, AL

It might be actually possible in the distant future...but we're a long way off from that. The concept of somehow uploading 1 quadrillion (10 to the 15th) neural connections with variable strengths for each one sounds like a computational nightmare!!

A philosophical question: would a human cyborg have a soul? Religions will have a field day with that one...is the concept of soul solely the sum of all those neural pathways and connections, or does it include some element separate from the physical brain??

June 2, 2013 at 4:48 p.m.RECOMMENDED1

archer717Portland, OR

Immortality can't be bought, Mr. Itskov. It has to be earned. It was earned by a few great minds and spirits like Shakespeare, Beethoven and Einstein. But not by narcissistic fools like yourself.

June 2, 2013 at 4:48 p.m.RECOMMENDED1

Bushy Van EckSouth Africa

Creating an Avatar that looks like and mimics a human’s facial expression and even capable of reproductive voice simulations is one thing.

Creating an Avatar that can think for itself even in a very primitive intelligible way is a far cry from reality. Until this day scientists is not even capable of understanding the very basic realities of our existence. This is quite evident when looking at human psychology and all related phenomenon’s that certainly go hand in hand. Till this day not even a single living organism has been created but please corrects me if I’m wrong.

We are not even capable of grasping a simple thing like the realities of autism which is nothing more than a very basic deviation of the senses encapsulated in perceived time. I certainly admire the combined efforts of these scientists but having listened to some preliminary findings they are doomed from the very beginning. Only by understanding the true realities of our existence would you be capable of grasping the impossibility of such an attempt. However, such an attempt would certainly lead to new discoveries and gaining a better understanding of the human mind. With that said and with all due respect, I would challenge any and all involved in this project in a meaningful and open debate to justify my claim.

June 2, 2013 at 4:48 p.m.

BenMonterey, CA

The issue is not whether it can be done - Mr. Itskov's vision, or some version of it, is probably achievable - but whether it should be done.

It's to be hoped that Mr. Itskov, in his monkish moments of contemplation, will evaluate his plan by two standards: the precautionary principle and the law of unintended consequences. If he does so, he may discover that along with its utopian intention, the vision has darker and more forbidding implications.

It is in the mind that man's noblest but also most destructive impulses reside. Would transferring the contents of the brain from its biological setting to a fabricated setting somehow purge the mind of its greed, aggressiveness, capacity to hate? Or would it simply lock them into place, housed in an "immortal" structure that could wreak havoc more effectively and unstoppably than our frail mortal shells?

The original Sanskrit "avatar" means "passing down," as of a deity into an earthly form. When humans imagine themselves to be gods, the results can disastrous.

June 2, 2013 at 4:48 p.m.RECOMMENDED3

tolstoy's sisteru.s.

Survival, on a most basic level, always involves taking the life of something else, whether that be meat or vegetable. That's a cruel setup, and one we're seemingly stuck with. Could a kinder society be created with mechanical bodies that didn't need food? Say it's possible to upload our minds to a computer. Our thought patterns would still be based on the original cruel system. Society's ills and hoarding would just take different forms. To have a kinder world, we would need different thought patterns, and then we wouldn't be humans; we'd be something else.

Another problem to consider with a world of avatars is stagnation. One disadvantage of our mortal bodies is death, but an advantage is that we're also continually starting fresh... through our children. That enables growth and innovation. What happens when it's just the same population living on? Yes, wisdom would accumulate, but innovation wouldn't be the same. Starting fresh is vital to innovation. There can't be the same fresh start without birth--thereby building a new consciousness. Keep birth and lose death and you have a population problem; we would smother ourselves as a society. Lose both death and birth and we have probable stagnation.

Ultimately, I think this does boil down to one man not wanting to die. If Itskov truly wants good and kindness to come from this venture, he really needs to think it through. It's not just a matter of getting rid of our bodies. Our minds are based on the mortal world, too.

June 2, 2013 at 4:48 p.m.

JJEMSan Sebastian, Spain

Well, then a better idea would be reincarnation...

June 2, 2013 at 11:47 p.m.

Rhonda KovacNew York

This reminds me of a science fiction short story I read, I believe from the 1960's--unfortunately I cannot remember the author's name or the title--that is set in the distant future when medical technology is vastly advanced.. The story is in the form of a letter to an advice columnist--such as "Dear Abby". The writer of the letter describes how, because of a succession of various illnesses and injuries, one by one all of the parts of his body--imbs, internal organs, etc.--were replaced with artificial versions, culminating in his brain, which was transferred into an artificial brain computer such as what Itskov is talking about. At the end of the letter, the writer asks, "My question is, Am I still me?"

June 2, 2013 at 4:48 p.m.

DPSea

Sorry Guys ,but you really think we need MORE not LESS of humans on this planet ? Humans have & do,destroy pretty much everything they touch. And now you are figuring we need MORE ,for Longer? How about waiting 10,000 - No ,100,000 years when (if we survive) we may have grown beyond our Birth Pangs & Infantile stupidity which we seem to be mired in?

I know Mr. Itskov ,you don't want to die ,and probably think ,because you were clever enough to make all that money that you don't deserve to Die. But guess what - you will.

How about spending some of those Dollars towards fixing Humans Destructive nature ,instead of Wasting the $ on your desperate & Foolish attempt to Skirt Death. Wow...

June 2, 2013 at 4:48 p.m.RECOMMENDED1

AlexLos Angeles, CA

It struck me on the fourth page of this article that technology will not save us. Tech is like money: it amplifies what's already there. This new technology will make all the injustice and inequalities worse, because humans have been taught one system, a perfect imposition of our animal greed onto society, and we have operated under this system for a long, long time. Inventions like this are the brand new thing, but we have to earn it, have to solve our fundamental problems before a single avatar is built, lest we compound the terribleness of our society and make it worse.

June 2, 2013 at 4:48 p.m.

serbanMiller Place

Verified

Whether anything like this will be possible in the far future is unpredictable. What is predictable is that we understand too little at present about how the brain functions and how to approximate its function with computers for anything like it to be remotely possible in the foreseeable future.

June 2, 2013 at 4:26 p.m.RECOMMENDED1

h2onymph1Cupertino, CA

Is it possible? Probably yes. But should we? I say no.

The greatest technological invention ever created is actually our own human body. We should be spending more money on research into understanding the mind-body technology behind human potential. We don't need to create something artificial outside of ourselves. Our bodies were designed to heal itself, and our mind creates reality. While modern (Western) culture may push in artificial directions, the lore of many ancient cultures suggest that the true nature of reality can be controlled from within, and there is no need to push and build outwards with technology. Today, in our modern societies, nascent mind-body research and Einsteinian physics is only just beginning to scratch the surface of this potential, but not enough is being done to explore these promising avenues.

I wish there there would be more money and media focus put behind that kind of research instead. That would be something worth getting excited over.