The Brotherhood of Eternal Love

From Flower Power to Hippie Mafia:

The Story of the LSD Counterculture

Stewart Tendler and David May

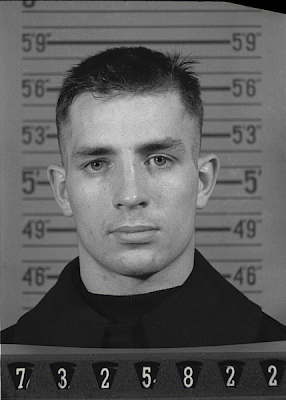

Nick Sand was not the sort of chemist to spend his time sitting in a faculty building looking up formulae. He was a graduate of the bath-tub school of chemistry and at the age of twenty-six he was a senior member of the alumni, the Prohibition bootlegger reincarnated. A bright, energetic New Yorker, he sought nothing else in life but to make chemicals and money. There are those who say that Sand to his dying day will be working somewhere in a laboratory. He was street-wise where Scully was innocent, with an ego every bit as big—maybe bigger -than Owsley's.

He began his career in his mother's home in an apartment block in Brooklyn while still at school. In the early 1960s he spent a year away at college, came home and worked for a degree in sociology and anthropology at Brooklyn College. A devotee of Gurdjieff, a Graeco-Russian mystic, Sand belonged to a New York group dedicated to his teachings, which may well have led him into Greenwich Village and the LSD scene. From there he travelled up to Millbrook and grew to know Leary well.

After finishing college in 1966, Sand worked for a short while as a census-taker for the New York port authority the only legal job he is ever known to have had—and then established the Bell Perfume Company with Alan Bell, a childhood friend. Sited opposite the local police station and the Hall of Justice, the company set out to manufacture mescaline, DMT, the drug made by Owsley at Point Richmond, and DET, another hallucinogenic closely related to DMT. It was there Sand established his reputation by cooking up a bath-full of DMT. Unlike Owsley, Sand was not particular about the purity he achieved, and the DMT came out a yellowish orange rather than the salt-like crystal it should have been. The impurities in DMT are the same substances which give faeces its smell. Sand's DMT stank.

By the time Owsley turned up at Millbrook, Sand had other problems. The New York police were taking an interest in his activities—he had a conviction for possession of marijuana—and the time might well be ripe to make a move westwards. Leary was constantly visiting California now and Hitchcock was interested in going out there as well. Owsley expounded the virtues of STP and the pleasures of HaightAshbury. Sand loaded up a truck with equipment and chemicals, recruited a partner for the West Coast and began driving but, being Sand, there just had to be that little disaster on the way.

State Patrolman J. J. Johnson never benefited from the BDAC men's campus education. He was cut more in the Broderick Crawford mould of law-enforcement officer, not a man for finesse. Two hundred miles north-west of Denver, Johnson was guarding a weigh station at Dinosaur, near the township of Craig, in late March 1967. Trucks are supposed to be weighed at weigh stations to make sure they are not travelling overloaded and therefore being a menace to themselves and other highway users. That was what the law said and that was what Officer Johnson was there to make sure happened. But there was this ageing truck with California plates which did not seem to be stopping.

Sand, with his equipment and chemicals on board, was not about to stop for anything as trivial as a weigh station in the middle of nowhere. The next thing he knew as the weigh station disappeared behind him was the sound of a police siren: Officer Johnson in hot pursuit.

Sand pulled over, to find himself covered by a large police revolver in the unwavering hand of the state patrolman. Ten days in the county jail.

But the bad luck had only just started. A drug store in Craig, where Sand was jailed, had been burgled the night before the weigh station incident; the local sheriff got to thinking about this and the truck and the New Yorker driving it. Innocent people do not evade weigh stations. Backed by a posse, the sheriff broke into Sand's truck.

Next thing, the telephone lines to BDAC regional headquarters were fairly burning as the good sheriff summoned expert help. The sheriff and the BDAC men proudly announced they had uncovered a mobile laboratory with 20 lb. of 'LSD', valued initially at $336 million. Since the drug was not pure but apparently only partially processed, the estimate rapidly dropped to $1.5 million.

However, the law officers' jubilation soured. Was the search lawful without a warrant? The BDAC men rounded on the sheriff for acting in haste. Sand left them to argue the point. Freed on bail, he was now bereft of both equipment and chemicals. (The truck's contents were eventually returned two years later because the search had been unlawful.) He could not even return to New York for fresh supplies because, the day after his arrest, the old laboratory was destroyed by fire and Alan Bell died. The story Sand gave to friends was that Bell was the victim of the same imprecision which made his DMT stink: he had fallen asleep in the laboratory, leaving a flame burning.

It was a somewhat frustrated Sand who arrived in San Francisco, but Owsley saved the day. Instead of one laboratory he would have two. Sand would set up shop in San Francisco and Scully would continue in Denver. The output would be tableted and distributed by Owsley.

Provided with the formula for STP, Sand, the hustler, decided on a short-cut and sent it off to the chemical suppliers he had used in New York. Could they perhaps make up this formula? Back came a negative reply and his cheque. If it had to be a laboratory, then so be it... but Sand, the chemist, vowed that his would pump out STP like never before.

In July 1967, Sand started business. The laboratory was hidden in an area on the east side of San Francisco between two large agricultural markets. In a rented house overlooking the approach road, Sand kept a sentry ready by a telephone to warn of approaching police.

But the greatest danger was in the laboratory itself. The pride of his laboratory was a 150-gallon soup-vessel bought from a restaurant supply store in San Francisco. Scully had designed a piece of equipment with which Sand could 'cook up' STP. The vessel, six feet high and three feet across, was Sand's interpretive short-cut on Scully's careful drawings. At first no one noticed anything. Sand and his helpers worked busily away round the soup-vessel as it built up heat, the top secured by a pressure-cooker lid. Then someone started coughing. The heat was really rising in the vessel now. Someone else was coughing. Then everybody began wheezing and gasping for air. There was a mad rush for the doors and fresh air.

There comes a point in the process when noxious fumes are given off, especially if the process is allowed to overheat. Sand had allowed his wonderful soup-vessel to overheat, pouring out hydrochloric acid. When he got back into the laboratory, Sand could look at the sky through the hole in the roof eaten away by the acid.

As Sand corrected his mistake and made his repairs, STP was already being distributed from Denver. Owsley had ignored his deal with Scully, passing out 5,000 doses for the summer solstice festival organized in Haight. The dosages were high—Owsley had distributed 30-milligram doses at Millbrook earlier in the year and left the place floored for three days—and warnings rapidly spread through Haight. Attempts to stifle the effects with thorazine, the standard response to bad LSD experiences, only seemed to make things worse. Finally 'the Alchemist' appeared in the offices of the Berkeley Barb to put the record straight. STP, he understood, was made 'by people who considered it a sacrament and if it was not free it was not STP'.

The Denver laboratory produced at least 2 lb of STP before Owsley finally remembered where he had put the lysergic acid. In the early autumn, Owsley and Scully finished the cache to produce more White Lightning and what became famous among devotees as 'Pink Owsley'. Owsley was refining his work with greater and greater skill. He devised a system for recycling impure material from the purifying process and using it again. Early tablets were uneven in content but Owsley worked to rectify this, trying to ensure that LSD could not be rubbed off or soaked away with the sweat of a hand.

Although at his peak, Owsley may well have considered retiring. The cache of lysergic acid was finished and the attractions of Haight were beginning to pall under the deluge of tourists—not to mention the men from BDAC. There were also the profits of Owsley's productions. By the winter of 1967 over $320,000 were salted away in safe-deposit boxes around San Francisco. Another $225,000 had been moved abroad, courtesy of Billy Hitchcock. The trip to 'Millbrook had not been uneventful. Near the estate, Owsley had been stopped by police and, reeking as usual of patchouli oil, he aroused their suspicions. Searching Owsley's car, they discovered a safe-deposit key for a New York box filled by Melissa Cargill, his girlfriend, who flew across the United States to top up the box. A panic-stricken Owsley contacted Hitchcock... who knew just what to do. Since the 1960s, he had acted as a broker for the Fiduciary Trust Company, based in the Bahamas and an offshoot of Bernie Cornfeld's ill-starred Investors' Overseas Services empire. Charles Rumsey, Hitchcock's friend, was the New York lawyer for Fiduciary. The two opened the safe-deposit on behalf of Owsley, and in the bedroom of Hitchcock's New York apartment the money was passed over to the general manager of Fiduciary to open the 'Robin Goodfellow' account. Owsley also had an account in London, contents never revealed. The task may have been divine, but the fruits were certainly worldly. By comparison, Scully earned little more than $6,000 a year with Owsley, and his ambitions went no higher than a plain Chinese meal.

While Owsley was meditating on his future and organizing the tableting, Scully was still insistent on his goal of turning the world on. Owsley shook his head. Try Hitchcock, he said; he might just be interested. The young millionaire had first visited San Francisco after meeting Owsley; he liked what he saw. Millbrook, beset by feuds between the various esoteric tenants and the attentions of the police, was past its heyday. Haight was where it was at, and Hitchcock moved his life west.

Renting a house in the pleasant San Francisco suburb of Sausalito, home of artists and LSD luminaries, he maintained his business life through a secretary in New York who kept in touch by telephone. Through Leary, he met the West Coast psychedelic movement; and through Owsley, he stepped into its illicit side. Once again he found his wealth attracted attention. While working on the STP laboratory, Sand popped up clutching the formula Scully had given him, claiming it was the original, promising he had the help of the inventor and asking for finance.

Hitchcock demurred but promised to stay in touch. Owsley introduced his new friend to the Angels. Hitchcock warmed to Owsley's suggestion that perhaps he, Hitchcock, might like to move in. He moved another $90,000 for the chemist to the Bahamas. Short of cash to operate, Scully borrowed from Hitchcock on behalf of Owsley -whose credit was clearly good—and then Sand, Scully and Hitchcock got together for a conference. If Owsley did quit, maybe... That was always providing the damned BDAC agents...

Both Hitchcock and Sand had met Tracey—Terry the Tramp—through Owsley. The chemist's parting gift to his friends among the Angels was a cache of LSD crystals the BDAC men had missed and a new connection for their drug supplies. According to Tracey's number two, Wethern, Sand was more than eager to fill the breach, offering a weekly supply of LSD worth $50,000 in exchange for $40,000. The Angels were happy with the arrangement sweetened by samples of DMT, the drug Sand had made in New York and which he handed round at the conference. If the Angels liked the drug, he would make it for them in return for a supply of raw materials. The Angels did indeed like the quick-acting drug and agreed to supply chemicals.

The first delivery of LSD went smoothly enough. Sand handed over 27,000 yellow tablets which Wethern circulated among other Angels and in Berkeley. 'Me word came back that they were every bit as good as anything Owsley had made. But as the system regularized, complaints started to come back from the streets that customers were not getting LSD. Wethern personally 'interviewed' Sand who admitted that he still had some STP to get rid of before beginning LSD production. The Angels, lacking any other supplier, were forced to accept the situation and sell STP until Sand had exhausted his stock. Sand should have realized then the dangers he could face if he tried to be too clever.

The STP brought further problems when 12,000 doses hidden in a garage were transformed into a useless blob by moisture. Tracey and Wethern decided to force Sand to take back the wasted material and drove the seventy-five miles from San Francisco to Cloverdale where Sand was living on a rented ranch. Wethern, having failed to shoot the lock off the ranch gates, climbed over with Tracey. The two massive Angels stalked past the duck pond, the geodesic dome, the orchard and the tepees installed by Sand, towards the main house. The inhabitants greeted the visitors cautiously. Witnesses to the visit said that the Angels, in their usual tactless way, toted guns at women and children, held everybody up and then took anything of value they could find. Wethern denies this but admits that he and Tracey practised with their guns on a hillside until a worried Sand arrived to replace the useless drugs.

Peace returned. However, the Angels began to discover they were now having difficulties in moving any STP at all. No one seemed to want to buy. In their own inimitable fashion, the Angels began to investigate the state of the market. Their conclusions resulted in a very unusual business conference.

Wethern parked his car outside a cemetery. In the back Sand was jammed in between several large Angels. Why, Wethern wanted to know, was there so much trouble moving STP? Why Nick? Why Nick?

The Angel answered for him. The gang had paid a visit to a dealer who had always been a good customer, on the boat that he kept. With a rock and a rope round his neck the dealer explained that he no longer wanted Angel STP because he could get it at a better price.

Do you know who from, Nick? the Angel asked. Guess. You.

The revelation was the signal for Sand to be pistol-whipped. As he slumped, bleeding, Wethern still wanted to know how Sand could keep up his supplies to the Angels and run another deal on the side. It is not recorded how long Sand took to pluck up the courage and reply. But finally he did.

The raw materials Sand had requested from the Angels to make their DMT had been diverted to STP production. Chemicals stolen by the Angels from factories, laboratories and universities had been used to cheat them. Wethern estimated that Sand had been given, free, enough chemicals to make something like 8 million STP doses.

Before Sand left the car, Wethern pressed his nose to the window and made him stare at the tombstones across the road. The message was very clear.

http://www.druglibrary.net/schaffer/lsd/books/bel3.htm