Screenland

Alex Jones Under Oath Is an Antidote to a ‘Post-Truth’ AgeBy Charles Homans / April 17, 2019

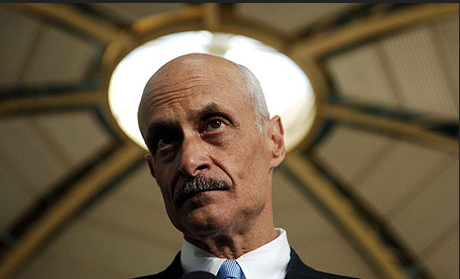

Five days after Attorney General William Barr released his expectation-deflating summary of the investigation into the Trump campaign’s suspected Russia connections, a pair of videos appeared on YouTube, labeled “Alex Jones / Sandy Hook Video Deposition.” The hundreds of thousands of views those videos have accumulated attest to their appeal as a #Resistance consolation prize: Maybe it’s not a habitually lying president, but at least someone is getting called to account, under oath, for his role in the post-truthification of American public life.

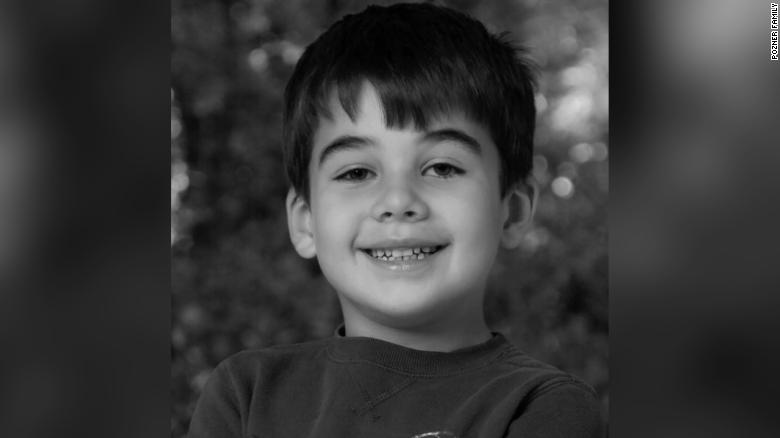

Jones, the Trump-endorsed proprietor of the conspiracy-mongering Infowars media empire, is being sued for defamation by 10 families of children who were murdered at Sandy Hook Elementary School in 2012. That mass shooting, Jones maintained until recently, was a hoax, perpetrated with the connivance of the victims’ parents — many of whom have found themselves harassed, threatened and in some cases hounded from their homes by believers in this conspiracy theory.

Some ambivalence is probably in order about the practice of publicly posting deposition videos. But in the particular case of Alex Jones — who swam happily in YouTube’s abyssal depths before being mostly banned for hate-speech-policy violations last August — you have to at least appreciate the karmic elegance of it. The deposition is the sort of thing you could imagine him experiencing in a particularly unpleasant dream. In the video, he sits at a table, much as he sits behind the desk on his flagship “The Alex Jones Show,” but he is not in charge of the production. Instead, he is compelled to answer the questions of a young attorney named Mark Bankston (offscreen and unseen), who over the course of more than three hours meticulously deconstructs the world that Jones has conjured for his audience.

Video

2:16Alex Jones Sandy Hook Deposition

CreditCreditVideo by Kaster Lynch Farrar & Ball LLP

Advertisement

Bankston seems less interested in the “whys” of Jones’s universe — the ultimately unsolvable riddle of how fully Jones believes what he says on the air — than he is in the “hows”: the way information gets chopped and screwed on Infowars, distended and looped and played back into the public discourse. In a way, it’s an examination of the whole unstable architecture of influence in today’s politics. When a particularly cancerous meme surfaces in Trump’s Twitter feed, or when white supremacists suddenly materialize en masse in the streets of a college town, the operative question now always seems to be: Where the hell did that come from?

At one point, Bankston dials in on an April 2017 broadcast in which Jones and his colleague Rob Dew discuss the police inspection of the Sandy Hook school grounds after the shooting. “They’re finding people in the back woods that are dressed up in SWAT gear,” Dew says. Jones, in the video, agrees.

Bankston, in the deposition, reads this aloud and asks Jones: “That’s not true, is it?”

“I saw it on the national news,” Jones says.

“You saw somebody in SWAT gear in the woods?”

“Black and camouflage — the police arrested him, they said there was a SWAT drill in the area?” he offers hopefully.

Advertisement

“No, Mr. Jones, I’m asking you: Did you see a video of a man in SWAT gear being arrested?”

Jones, like most conspiracy theorists, presents himself as a close reader of reality, scrutinizing the gaps in the official narrative that reveal the big lie. But when that close reading is itself subjected to a close reading, you realize that Jones’s appeal comes not from his attention to details but from the velocity with which he blows past them — the way he hurtles through an asteroid belt of informational debris on his way to explicating the galaxy-scale perfidy of his villains. The law, and Bankston, do the opposite. They bore patiently inward, toward particularity.

Jones pauses, stares off-camera, blinks. “I saw the helicopter, talking about it, they said they later arrested the man.”

“So when you told your audience he was dressed up in SWAT gear, that’s just something you made up, isn’t it? There’s nobody dressed up in SWAT gear.”

Editors’ Picks

Royal Baby Traditions Are Real. Harry and Meghan Are Shaking Them Up.

With the Birth of My Son, I Stopped Hiding

‘I Want What My Male Colleague Has, and That Will Cost a Few Million Dollars’

“I do remember that being on the news,” Jones says.

“What being on the news?”

“The helicopter and the man behind the school. And the report of the guy in the SWAT gear and the police saying they arrested him, and later they said they didn’t —”

“Yeah, it’s two reporters with cameras! There’s reports about it. There’s no man in SWAT gear in that video, is there? That’s just something you made up.”

“Nope, I didn’t make it up,” Jones insists, defiantly but also a little plaintively.

Writing in The Daily Beast two years ago, the conservative commentator Matt Lewis placed Jones in the lineage of right-wing radio talkers like Rush Limbaugh, who had effectively reverse-engineered politics from pro-wrestling-style confrontational entertainment. The problem is that “politics is inherently different,” Lewis wrote. “The stakes are higher. And since ideas have consequences, our words can have grave consequences.”

Sign up for The New York Times Magazine Newsletter

The best of The New York Times Magazine delivered to your inbox every week, including exclusive feature stories, photography, columns and more.

Advertisement

This was a sly turn of phrase. “Ideas have consequences” has been a conservative battle cry since 1948, when the acerbic anti-modernist Richard M. Weaver published a book-length polemic by that title bemoaning the decline of universal truth. “On the verbal level, we see ‘fact’ substituted for ‘truth,’ ” Weaver wrote. “With what pathetic trust does he” — the “average man” — “recite his facts! He has been told that knowledge is power, and knowledge consists of a great many small things.”

As with most adages, the use of “ideas have consequences” has become dumber with time. In the mouths of figures like Limbaugh and Dinesh D’Souza, it calcified into a sort of pretentious playground taunt: You liberals have facts, but we have ideas! Alex Jones surely would have appalled Weaver, but he represents the logical, self-parodying extreme of this rhetorical pose, filling in the outlines of an increasingly conservative-traditionalist worldview with ridiculous particulars about demons reincarnated as Clintons. Last week, Candace Owens, the video blogger and recent Infowars on-air presence, was called by House Republicans to testify in a hearing on white supremacy, where she insisted that the so-called Southern strategy — the Nixon-era Republican Party’s wooing of white Southern conservatives — “never happened.” It is not really possible anymore to say where Jones’s universe ends and mainstream conservatism begins.

What’s commonly lamented as post-truth politics is, if we’re being precise about it, really post-fact politics: not the death of a higher truth (belief in which has proved robust enough) but of that “great many small things.” Small things like whether or not there was a man in SWAT gear in those woods. They might not matter in politics anymore, but they do in a courtroom. “We have a right in this country to question things,” Jones protests at one point in the deposition. To which Bankston replies: “I’m not saying what you didn’t and did have a right to do. I’m just asking you what you did.”

Charles Homans is the magazine’s politics editor.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of The New York Times Magazine delivered to your inbox every week.

A version of this article appears in print on April 20, 2019, on Page 7 of the Sunday Magazine with the headline: Third Degree. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper | SubscribeBy Charles Homans

April 17, 2019

Five days after Attorney General William Barr released his expectation-deflating summary of the investigation into the Trump campaign’s suspected Russia connections, a pair of videos appeared on YouTube, labeled “Alex Jones / Sandy Hook Video Deposition.” The hundreds of thousands of views those videos have accumulated attest to their appeal as a #Resistance consolation prize: Maybe it’s not a habitually lying president, but at least someone is getting called to account, under oath, for his role in the post-truthification of American public life.

Jones, the Trump-endorsed proprietor of the conspiracy-mongering Infowars media empire, is being sued for defamation by 10 families of children who were murdered at Sandy Hook Elementary School in 2012. That mass shooting, Jones maintained until recently, was a hoax, perpetrated with the connivance of the victims’ parents — many of whom have found themselves harassed, threatened and in some cases hounded from their homes by believers in this conspiracy theory.

Some ambivalence is probably in order about the practice of publicly posting deposition videos. But in the particular case of Alex Jones — who swam happily in YouTube’s abyssal depths before being mostly banned for hate-speech-policy violations last August — you have to at least appreciate the karmic elegance of it. The deposition is the sort of thing you could imagine him experiencing in a particularly unpleasant dream. In the video, he sits at a table, much as he sits behind the desk on his flagship “The Alex Jones Show,” but he is not in charge of the production. Instead, he is compelled to answer the questions of a young attorney named Mark Bankston (offscreen and unseen), who over the course of more than three hours meticulously deconstructs the world that Jones has conjured for his audience.

Video

2:16Alex Jones Sandy Hook Deposition

CreditCreditVideo by Kaster Lynch Farrar & Ball LLP

Advertisement

Bankston seems less interested in the “whys” of Jones’s universe — the ultimately unsolvable riddle of how fully Jones believes what he says on the air — than he is in the “hows”: the way information gets chopped and screwed on Infowars, distended and looped and played back into the public discourse. In a way, it’s an examination of the whole unstable architecture of influence in today’s politics. When a particularly cancerous meme surfaces in Trump’s Twitter feed, or when white supremacists suddenly materialize en masse in the streets of a college town, the operative question now always seems to be: Where the hell did that come from?

At one point, Bankston dials in on an April 2017 broadcast in which Jones and his colleague Rob Dew discuss the police inspection of the Sandy Hook school grounds after the shooting. “They’re finding people in the back woods that are dressed up in SWAT gear,” Dew says. Jones, in the video, agrees.

Bankston, in the deposition, reads this aloud and asks Jones: “That’s not true, is it?”

“I saw it on the national news,” Jones says.

“You saw somebody in SWAT gear in the woods?”

“Black and camouflage — the police arrested him, they said there was a SWAT drill in the area?” he offers hopefully.

Advertisement

“No, Mr. Jones, I’m asking you: Did you see a video of a man in SWAT gear being arrested?”

Jones, like most conspiracy theorists, presents himself as a close reader of reality, scrutinizing the gaps in the official narrative that reveal the big lie. But when that close reading is itself subjected to a close reading, you realize that Jones’s appeal comes not from his attention to details but from the velocity with which he blows past them — the way he hurtles through an asteroid belt of informational debris on his way to explicating the galaxy-scale perfidy of his villains. The law, and Bankston, do the opposite. They bore patiently inward, toward particularity.

Jones pauses, stares off-camera, blinks. “I saw the helicopter, talking about it, they said they later arrested the man.”

“So when you told your audience he was dressed up in SWAT gear, that’s just something you made up, isn’t it? There’s nobody dressed up in SWAT gear.”

Editors’ Picks

Royal Baby Traditions Are Real. Harry and Meghan Are Shaking Them Up.

With the Birth of My Son, I Stopped Hiding

‘I Want What My Male Colleague Has, and That Will Cost a Few Million Dollars’

“I do remember that being on the news,” Jones says.

“What being on the news?”

“The helicopter and the man behind the school. And the report of the guy in the SWAT gear and the police saying they arrested him, and later they said they didn’t —”

“Yeah, it’s two reporters with cameras! There’s reports about it. There’s no man in SWAT gear in that video, is there? That’s just something you made up.”

“Nope, I didn’t make it up,” Jones insists, defiantly but also a little plaintively.

Writing in The Daily Beast two years ago, the conservative commentator Matt Lewis placed Jones in the lineage of right-wing radio talkers like Rush Limbaugh, who had effectively reverse-engineered politics from pro-wrestling-style confrontational entertainment. The problem is that “politics is inherently different,” Lewis wrote. “The stakes are higher. And since ideas have consequences, our words can have grave consequences.”

Sign up for The New York Times Magazine Newsletter

The best of The New York Times Magazine delivered to your inbox every week, including exclusive feature stories, photography, columns and more.

Advertisement

This was a sly turn of phrase. “Ideas have consequences” has been a conservative battle cry since 1948, when the acerbic anti-modernist Richard M. Weaver published a book-length polemic by that title bemoaning the decline of universal truth. “On the verbal level, we see ‘fact’ substituted for ‘truth,’ ” Weaver wrote. “With what pathetic trust does he” — the “average man” — “recite his facts! He has been told that knowledge is power, and knowledge consists of a great many small things.”

As with most adages, the use of “ideas have consequences” has become dumber with time. In the mouths of figures like Limbaugh and Dinesh D’Souza, it calcified into a sort of pretentious playground taunt: You liberals have facts, but we have ideas! Alex Jones surely would have appalled Weaver, but he represents the logical, self-parodying extreme of this rhetorical pose, filling in the outlines of an increasingly conservative-traditionalist worldview with ridiculous particulars about demons reincarnated as Clintons. Last week, Candace Owens, the video blogger and recent Infowars on-air presence, was called by House Republicans to testify in a hearing on white supremacy, where she insisted that the so-called Southern strategy — the Nixon-era Republican Party’s wooing of white Southern conservatives — “never happened.” It is not really possible anymore to say where Jones’s universe ends and mainstream conservatism begins.

What’s commonly lamented as post-truth politics is, if we’re being precise about it, really post-fact politics: not the death of a higher truth (belief in which has proved robust enough) but of that “great many small things.” Small things like whether or not there was a man in SWAT gear in those woods. They might not matter in politics anymore, but they do in a courtroom. “We have a right in this country to question things,” Jones protests at one point in the deposition. To which Bankston replies: “I’m not saying what you didn’t and did have a right to do. I’m just asking you what you did.”

Charles Homans is the magazine’s politics editor.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of The New York Times Magazine delivered to your inbox every week.

A version of this article appears in print on April 20, 2019, on Page 7 of the Sunday Magazine with the headline: Third Degree. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper | Subscribe

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/17/maga ... -oath.html