Moderators: Elvis, DrVolin, Jeff

In Bolsonaro’s Brazil, a Showdown Over Amazon Rainforest

The river basin at the center of Latin America called the Amazon is roughly the size of Australia. Created at the beginning of the world by a smashing of tectonic plates, it was the cradle of inland seas and continental lakes. For the last several million years, it has been blanketed by a teeming tropical biome of 400 billion trees and vegetation so dense and heavy with water, it exhales a fifth of Earth’s oxygen, stores centuries of carbon, and deflects and consumes an unknown but significant amount of solar heat. Twenty percent of the world’s fresh water cycles through its rivers, plants, soils, and air. This moisture fuels and regulates multiple planet-scale systems, including the production of “rivers in the air” by evapotranspiration, a ceaseless churning flux in which the forest breathes its water into great hemispheric conveyer belts that carry it as far as the breadbaskets of Argentina and the American Midwest, where it is released as rain.

In the last half-century, about one-fifth of this forest, or some 300,000 square miles, has been cut and burned in Brazil, whose borders contain almost two-thirds of the Amazon basin. This is an area larger than Texas, the U.S. state that Brazil’s denuded lands most resemble, with their post-forest landscapes of silent sunbaked pasture, bean fields, and evangelical churches. This epochal deforestation — matched by harder to quantify but similar levels of forest degradation and fragmentation — has caused measurable disruptions to regional climates and rainfall. It has set loose so much stored carbon that it has negated the forest’s benefit as a carbon sink, the world’s largest after the oceans. Scientists warn that losing another fifth of Brazil’s rainforest will trigger the feedback loop known as dieback, in which the forest begins to dry out and burn in a cascading system collapse, beyond the reach of any subsequent human intervention or regret. This would release a doomsday bomb of stored carbon, disappear the cloud vapor that consumes the sun’s radiation before it can be absorbed as heat, and shrivel the rivers in the basin and in the sky.

The catastrophic loss of another fifth of Brazil’s rainforest could happen within one generation. It’s happened before. It’s happening now.

Views of deforestation’s aftereffects in the Amazon on Sept. 24, 2016. The rate of deforestation in Brazil peaked in 2004 and entered a decade of decline, but it began to creep up again in 2012, driven by the global commodity boom and an expanding agribusiness sector.Photos: Gabriel Uchida

1The Red Zone

One morning in April, a dugout powered by a small outboard motor appeared at a bend just upriver of the village of Kamarapa, a settlement of Apurinã Indians in Brazil’s southwestern Amazon. The dozen Apurinã squeezed inside the narrow craft represented the last of several expected delegations. The boats had been arriving since the previous morning, gliding to rest on muddy jetties after four, six, 10-hour journeys through the deep-water forest maze of the southern Amazonian floodplain during the winter rainy season.

The Apurinã were gathered to discuss the emergency. In recent years, outlaws with chainsaws, known as land-grabbers, or grileiros, “locusts,” have been cutting deeper into Brazil’s Indigenous territories and other protected forests throughout the Amazon. Emboldened by the October election of Jair Bolsonaro as Brazil’s president, they are pushing more brazenly into places like Apurinã land in the roadless depths of Amazonas, the country’s biggest state and home to the world’s largest standing tracts of unbroken rainforest. “With Bolsonaro, the invasions are worse and will continue to get worse,” said Francisco Umanari, a 42-year-old Apurinã chief. “His project for the Amazon is agribusiness. Unless he is stopped, he’ll run over our rights and allow a giant invasion of the forest. The land grabs are not new, but it’s become a question of life and death.”

Over the next two days, a hundred Apurinã men, women, and children met in a riverside thatched-roof meeting hall to confront their fears and make plans. They did so against the ticking of the Amazon’s monsoonal clock. In July and August, the rains will stop and the rivers will fall, adding hours and days of boat travel between villages and the nearest frontier towns. The coming of dry season also heralds the next wave of burnings. Last year, after government satellites detected smoke plumes, a group of Apurinã men arrived to find 1,000 hectares of their ancestral forest gone. “We were shocked at the size of it,” said Marcelino Da Silva, one of the men. To create pasture, the land-grabbers hacked miles of path through the forest with machetes and used motorcycles to transport long-blade chainsaws and drums of kerosene. The land being too remote for logging, they used even the most valuable trees for kindling, seeding the smoldering ashes with orchard grass dropped from helicopters.

Map: Soohee Cho/The Intercept

“We knew the red zone was moving toward us but didn’t expect it so fast from every direction,” said Da Silva, using the local term for the agribusiness frontier that has been advancing by fits into Amazonas from the south and east for five decades. “We know what happens when the state does nothing. We know how quickly the forest can disappear.”

“The land grabs are not new, but it’s become a question of life and death.”

Imazon, a Brazilian research center, reports deforestation in the first months of 2019 jumped more than 50 percent compared to the amount during the same period in 2018. Half of this deforestation has occurred illegally in protected areas, including hundreds of Indigenous lands that cover a quarter of Brazil’s Amazon and provide a crucial buffer for much of the rest. (In the rainforest bastion state of Amazonas, Indigenous lands account for close to a third of the standing forest.) The Indigenous groups of the region have seen this before. During the runaway deforestation of the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s, they witnessed and were devastated by an “arc of fire” that blazed along the routes of the first penetration roads into the western Amazon. By the late 1980s, a burning crescent swept down from the northern Amazonian city of Belém, through the states of Pará, Mato Grosso, Rondônia, and Acre. It burned brightest in Rondônia, where the smoke and ash from hundreds of raging fires were visible to the naked eyes of astronauts in high orbit.

BRAZIL - AUGUST 01: The dry bleeded amazonian forest in Amazonia, Brazil in August, 1989 - Fire in Rondonia state.

Charred forest in Amazonia, Brazil, in August 1989. Since the 1930s, the country’s right-wing governments have called for the settling of the rainforest in nationalist terms.

Photo: Antonio Ribeiro/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

As it did then, today’s reignited arc of fire signals the advance of an agribusiness frontier dominated by cattle and soy. Bolsonaro and his allies in Congress and Amazonian state governments vow to accelerate this advance in the name of progress. Doing so will require eliminating the young laws and agencies established to protect the rainforest, its supernova of life that accounts for most of the planet’s species, and its traditional Indigenous inhabitants, whose very existence Bolsonaro and his ministers have cursed and denied, and whose moral and spiritual challenge they fear but do not comprehend.

Apurinã assemblies are garrulous affairs even by the standards of participatory village democracy. In their language, Apurinã means “the people who talk,” a habit encouraged by their fondness for awyry, a bright green stimulant made from powdered forest seeds. Punctuated by the sounds of awyry sniffed through polished animal bones, the proceedings in early April lasted until darkness crept over Kamarapa. The people who talk had a lot to discuss: Expanded armed foot patrols. A network of monitoring stations equipped with radios. Deeper cooperation with neighboring ethnic groups, including traditional enemies. Outreach to potential allies in Brazil and the publics and governments of Europe and Asia, the main markets for Brazilian beef and soy. “We are doing what we can, organizing, monitoring, and petitioning,” said Fabiana Apurinã, a bright-eyed woman of 23 who attended the assembly from a village several hours downriver. “We are warriors and will mobilize to defend ourselves and the forest. But we need help.”

uru-house-1562182557

A child runs inside an Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau house in the village of Tribe 623 on June 10, 2019. White settlers in the 1970s waged war on Indigenous tribes and brought in devastating diseases; today there are 200 members of the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau remaining.

Photo: Gabriel Uchida

“We know what happens when the state does nothing. We know how quickly the forest can disappear.”

The assembly concluded by drafting a letter addressed to FUNAI, the embattled federal Indian agency, and the Federal Public Ministry, a powerful body of prosecutors within the Justice Ministry. It expressed alarm over the spreading red zone and the gutting of the state’s environmental monitoring and protection agencies. “Our territory is being invaded and we feel abandoned,” the letter read. “We ask the government to value our past and our deep connections to this land. The deforestation is advancing toward us. Our territory must be guaranteed for our children, according to our rights in the federal Constitution. If the government doesn’t do it, we’ll do it ourselves.”

2March To The West

No phone or radio signals reach the villages inside the Purús River floodplain of south Amazonas, so news from the outside comes slowly, on boats. On the morning of April 2, one brought word to Kamarapa of blood on the distant streets of Rio and Brasilia, where Bolsonaro supporters had brawled with protesters over a presidential decree that the armed forces commemorate the anniversary of the 1964 military coup. Bolsonaro, an ex-army captain, had campaigned on nostalgia for the scorched-earth policies and torture basements of the dictatorship. In villages like Kamarapa, where the junta is remembered for a regional program that amounted to a de facto extermination campaign, the news landed like a formal declaration of war.

“Bolsonaro is upgrading the dictatorship’s model; it’s the same racism, the same plans for the Amazon,” said a 34-year-old villager named Wallace, who wore a Che Guevara pendant under a necklace of jaguar teeth and whose fiery speeches, sprinkled with threats of secession, express the militant end of the Indigenous political spectrum within COAIB, an Amazon-wide Indigenous association he serves as a consulting member. “This government uses the language the generals used when they tried to destroy us and our culture. We fought back then and survived. We will again. What we need now is courage.”

Bolsonaro continues a far-right political tradition in Brazil that predates the 1964 dictatorship. It merges authoritarianism and panic over the perceived vulnerability of the Amazon to foreign conquest — or in its modern iteration, “internationalization.” In the 1930s, President Getúlio Vargas, a fascist sympathizer, called for a “March to the West” to settle, develop, and secure the rainforest for Brazil against the designs of its covetous neighbors. Thirty years later, the junta revived Vargas’s unrealized dream with Soviet-style five-year plans to “flood the Amazon with civilization.” Army engineers led dawn-to-dusk work crews that cut the first roads west of Mato Grosso, usually following old Indigenous hunting paths. State television ads promoted land and credit programs to spur transmigration from the overcrowded coasts and over-farmed savannah. They imagined an Amazon transformed: Out of an impenetrable wilderness, settlers would build a dense grid of ranches and small farms, each one connected to coastal ports and global commodity markets by a mighty network of roads and highways. The inhabitants of the forest, both Indians and non-Indigenous people living traditionally, would have to make way, adapt, and integrate. “Amazonian occupation will proceed as though we are waging a strategically conducted war,” said Castelo Branco, one of the generals who led the 1964 coup.

Boy observes soldiers and war tank during rally organized by then President João Goulart, known as Jango, at which base reforms were defended, in Rio de Janeiro, southeastern Brazil, March 13, 1964. The rally was allegedly one of the reasons behind the 1964 coup de d'état - Photo: Domício Pinheiro/Agência Estado/AE (Agencia Estado via AP Images)

A boy observes soldiers during a rally organized by then-President João Goulart in Rio de Janeiro on March 13, 1964. Current President Jair Bolsonaro, an ex-army captain, campaigned on nostalgia for the scorched-earth policies and torture basements of Brazil’s military dictatorship, which ruled for 21 years.

Photo: Domício Pinheiro/Agência Estado via AP

The junta’s homesteader occupation joined a graveyard of Amazonian dreams. The logistical challenges of settling the “green hell” were greater than the generals imagined, and the quality of the soils far worse. But if the regime failed to build a yeoman’s paradise on the ashes of the Amazon, it did produce the ashes. In 1988, when a new constitution was adopted three years after the return of civilian rule, more than a tenth of Brazil’s Amazon had been burned or degraded by government-supported settlers and industry. Brazil’s Indigenous population fared much worse, dropping from estimates of the low millions at the start of the century to around 200,000 at the end of the 1980s.

The Indigenous population has since rebounded fourfold, a resurgence that tracks to Brazil’s halting efforts to contain and reverse the deforestation wave that started swelling in the late 1960s. The 1988 constitution zoned 43 percent of the Amazon off-limits to industrial activity and land-clearing, an area covering hundreds of newly established parks, reserves, and more than 400 Indigenous territorial claims equaling an area twice the size of Spain. (It also placed rules delimiting activity on the other 57 percent.) It established an environmental monitoring and enforcement agency, IBAMA, and revamped FUNAI to help Indigenous communities protect their lands and develop sustainable forest industries. At the same time, international development banks tightened environmental and social conditions on aid and loans, and NGOs and activist campaigns led effective international boycotts, culminating in a landmark soy moratorium in 2006. Though the cutting and burning has never stopped, the rate of deforestation peaked in 2004 and entered a decade of decline.

Brazil’s Indigenous population dropped from estimates of the low millions at the start of the century to around 200,000 at the end of the 1980s.

The global commodity boom of the last decade put a stop to the progress. Legal and illegal deforestation began to creep up in 2012, driven by an expanding agribusiness sector and the growing political power of Brazil’s landowners in Congress, the ruralistas, who sought to roll back the land-use restrictions of the post-junta period. In 2016, they supported a soft coup against Dilma Rousseff, the center-left president, and provided cover for her scandal-plagued successor, Michel Temer, who lavished amnesty on land-grabbers and tried to loosen Brazil’s slavery laws. That same year, the central Amazonian state of Mato Grosso became the first to lift the ban on correntao, a notorious method for clearing forest that involves two tractors trawling an industrial bulk chain to uproot everything in its path.

My guide in Kamarapa and other villages of the southern Amazonas floodplain was a large and friendly but often brooding FUNAI official who asked that, to avoid reprisals as a government employee, his name not be used. Deeply versed in the history, biology, and cultures of the western Amazon, the official fit the romantic stereotype of the modern FUNAI employee: respectful and protective of his Indigenous partners, but conscious of the paternalism and worse that has always streaked through the culture of the agency. Watching him drop off jugs of fuel and check in with village leaders on the way to Kamarapa, it was clear the relationships were ones of mutual affection and trust.

As our powerboat headed downriver, making wide sweeps around the tops of submerged trees, the FUNAI official described a double emergency in the deep forest communities where he spends most of his time. “Around 2012, things started getting worse every year,” he said. “More invasions. Bigger burns. Budget cuts to FUNAI and IBAMA. Since the election, it gets worse by the day. Every single day there’s something.”

funai-sign-1562184449

A sign marking territory administered by FUNAI, the Brazilian federal Indian agency, was shot through as a signal that the government can’t keep loggers off the land.

On patrol with FUNAI and members of the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau, environmental police take stock of the damage wrought by illegal loggers in the tribe’s territory in Rondônia on April 17, 2018. According to the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau, a group of 15 men with machetes can clear lines through 20 kilometers of forest in a week.Photos: Gabriel Uchida

Within hours of being sworn in to office on January 2, Bolsonaro moved all forest policy to the Ministry of Agriculture, run by a particularly humorless ruralista named Tereza Cristina. The transfer included FUNAI’s longstanding role in demarcating Indigenous lands, which was added to the portfolio of the assistant minister for land affairs, Luana Ruiz, a lawyer whose family owns land that overlaps with Indigenous territory in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul. FUNAI, meanwhile, was moved from its home in the Justice Ministry to a new department housing the likewise demoted Ministry of Human Rights (lawmakers later reversed the move). The government then choked the agency of resources. Since January, FUNAI has been operating on 70 percent of its normal budget. Monitoring posts in high-risk areas across the Amazon have been abandoned, and long-planned operations scaled back, often leaving a single FUNAI employee to mediate violent land conflicts in remote tracts of contested forest.

“The Indigenous understood the connections between these fragile systems before we did. … Before anyone was talking about climate change, they were trying to warn us.”

Bolsonaro’s 44-year-old Minister of Environment Ricardo Salles has slashed staff and funding at FUNAI’s most important partner in government, the environmental monitoring and enforcement agency known as IBAMA. He has replaced the board of Brazil’s conservation institute, ICMBio, with officers from São Paulo’s military police, part of what Brasil de Fato, a weekly newspaper, calls the “militarization of the environmental sector.” One notable exception is the sustainable development office: After firing everyone, Salles chose to leave it empty.

The FUNAI official sketched the stakes of these decisions in stark terms. “In 30 years, maybe 15 with this government, all of the land between here and Lábrea could be deforested,” he said. Lábrea, the nearest frontier town, is hundreds of miles away.

He continued, “That would mean goodbye to the Purús and the infinity of plants the Apurinã have been studying for so long. The Purús and its rivers feed the Solimões”— an arm of the Amazon — “and the disruption would have huge downstream impacts in the north, where the deforestation hasn’t reached. The Indigenous understood the connections between these fragile systems before we did. The links between the forests and the rivers, how deforestation effects rain and weather. Before anyone was talking about climate change, they were trying to warn us.”

Cattle graze along B.R. 364 near the city of Ariquemes, in Rondônia, in 2018. The western Brazilian state has a $4 billion cattle industry, but by one estimate, a hectare of livestock or soy is worth between $25 and $250, while the same hectare of sustainably managed forest can yield as much as $850.

Photo: Gabriel Uchida

3The Road

Driving through central Rondônia on the two-lane blacktop of B.R. 364, it takes an act of sustained imagination to see the rolling landscape as Arima Jupaú knew it as a boy. Growing up in the late 1960s, the pastureland that now stretches to every horizon was covered by primary rainforest, lush and loud with life. He couldn’t imagine a forest’s edge, because none of the roughly 10,000 Jupaú living at the time had ever seen one. Only after 1970, when army engineers completed a dirt road connecting neighboring Mato Grasso to Porto Velho, Rondônia’s capital, did the concept of the frontier gain meaning. As settlers poured into the region on 364 — a half-million over the decade — the Jupaú learned to fear the frontier as a place of disease and violence, a buzzsaw that would cut them down to the verge of extinction. “We would retreat, and every time, when we looked out from the hills, we felt safe,” remembers Arima, one of 200 surviving Jupaú. “We thought they could never reach us. We thought the forest was too big.”

The brancos, the whites, kept coming. They came to farm, harvest wood, raise cattle, and mine the region’s stores of gold and cassiterite, the raw form of tin. The roughest of the settlers formed kill squads and massacred Indians where they found them. Arima’s first memories include seeing the removed skin of his uncle’s torso stretched out on sticks like a scarecrow, a message left by a group of nearby miners. The Jupaú waged war in return. “We told the whites to leave, but they didn’t listen,” said Arima, who led raids as an adolescent and was celebrated for the accuracy of his longbow. “We killed them and burned their houses. Too many to count.”

Deforestation is disrupting micro- and regional climates across the western Amazon and creating a measurable delay in the onset of a rainy winter season that is getting shorter and warmer.

In 1981, ravaged by tuberculosis, flu, pox, and measles, leaders from surviving bands of Jupaú met with FUNAI to discuss a truce. (During the meeting, a misunderstanding led an official to believe the tribe called itself the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau, which is how the Jupaú are known to the world.) “We accepted the peace because they said they would protect our land,” remembered Arima.

Around the same time, World Bank officials in Washington, D.C. accepted similar assurances from Brazilian generals seeking $1.6 billion to pull its failing “March to the West” from the literal and metaphorical mud. B.R. 364, the key artery in their development plan, was a swamp during the rainy winter season, and not much more passable during the dry summer months. To open the west, the road would have to be paved. The World Bank supported the idea over the advice of an in-house advisory group that warned paving 900 miles of B.R. 364 would accelerate the environmental and human rights catastrophes already unfolding in the region. This is exactly what happened. When international outcry forced the World Bank to suspend payments to the generals five years later, Rondônia had the highest deforestation rates in Brazil, led by a 3,000 percent increase in the cattle population, and was on track to be completely denuded by 1990 — the first “green desert” of the Amazon.

Tari Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau holds up a photo of the first contact between the tribe and officials from FUNAI. Aside from a dwindling number of uncontacted tribes and those living in voluntary isolation, many Indigenous groups want development and links to the world. But they are pushing for alternative models that preserve the forest.

Photo: Gabriel Uchida

I left Porto Velho on B.R. 364 with Arima’s soft-spoken 27-year-old son, Awapu, who lives in a four-family village on demarcated Indian land in the south of Rondônia with his parents, wife, and two children. In the following days, I would accompany him on patrols through the edge areas of Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau territory where land-grabbers were active in numbers not seen in a generation. As we drove south along the spine of Rondônia’s $4 billion cattle industry, all parched pasture and soy fields, Awapu described the multiplying flashpoints on Indigenous land erupting across the state. In Rondônia’s west, the Karipuna faced expanding invasions from three sides; in the northeast, the Suruí’s forests were so overrun with illegal diamond miners that the communities had split on whether to resist or resign and take a cut. (In March, the Department of Mines announced it would lift the post-junta ban on industrial mining in Indigenous territories.) It wasn’t just Indigenous lands, he explained. Illegal logging was on the rise in the state’s parks and bioreserves, a direct result of government policies and signals. In April, Bolsonaro personally intervened to block IBAMA agents from destroying heavy equipment confiscated during an anti-logging operation in Rondônia’s Jamari National Forest. The power to destroy the expensive tools of illegal loggers and miners is the agency’s most effective deterrent. But the president said in a video posted to social media: “It is not the orientation of this government to burn machinery.”

Its orientation of burning trees instead may soon undermine the foundation of the state’s agribusiness economy. Studies have begun to confirm something the villages first noticed decades ago: Deforestation is disrupting micro- and regional climates across the western Amazon and creating a measurable delay in the onset of a rainy winter season that is getting shorter and warmer. If Rondônia’s Indigenous lands are overrun, the state will become a synonym for disaster for the second time in living memory, only this time it will bring down the industries built on the cinders of the first great clearing. “The protected Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau forests hold the main river basins of the state,” said Daniel Peixoto, a federal police deputy who has led raids on land-grabbing syndicates tied to invasions of Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau land. “All of the water we have flows out from there. It’s the reason we don’t have drought. Even from the point of view of agribusiness and the cattle ranchers, it’s a strategic place to conserve.”

Members of the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau, including Arima and his son Awapu, patrol for illegal land-clearing. The protected Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau forests contain important river basins that feed the rest of the region, including land used by cattle ranchers and soy farmers.Photos: Gabriel Uchida

One morning at dawn, I joined Awapu for a breakfast of coffee and unsweetened açaí juice before traveling by canoe to the northwest edge of Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau land, a forested territory covering nearly 7,000 square miles in the south of Rondônia. The area is at the center of the local red zone, targeted by a rising number of invaders working on behalf of local cattle interests. With us were two older villagers, Djurip, who carried a bow and several bamboo arrows, and Potei, who carried a rusty hunting rifle. “The election made the grileiros fearless,” said Awapu, as we tied the canoe and entered the forest. “They know Bolsonaro thinks the same as them — that we don’t work, that we don’t deserve so much land. There are rumors the president will give them our territory. They think nobody will stop them.”

The Pastoral Land Commission has recorded more than 600 land-related murders in the country since 2003, most in the Amazon region, with a 20 percent increase in 2018.

For most of the morning we followed a monitoring path in silence, hiking through thick undergrowth draped with curtains of lianas. Potei led the way. He stopped in front of a crude but perceptible path that intersected with our own. The men spread out to investigate its dimensions. They returned wearing heavy expressions. Awapu knelt down, cleared some dirt, and drew a right angle with a stick. “They start with this ‘L’ shape,” he said, motioning toward the path. “A group of 15 men with machetes can clear lines through 20 kilometers of forest in a week. Marking the plot, making entrances. When the rains stop, they come back with chainsaws to cut the smaller trees and clear the way for tractors, if there is a road nearby. They burn what’s left. In November, before the rains start again, they seed the grass. It grows fast. Now it’s pasture. They sell it to a rancher who says he doesn’t know anything about land grabbing. It’s washed clean.”

Stopping the process before the burning and planting means confronting gangs of armed land-grabbers in isolated areas littered with the bones of a half-century of land conflict. As the government withdraws from the forest, other forms of deterrence will be needed, including Indigenous patrols that can move and communicate unseen and unheard, and whose serrated arrows may announce themselves with a whisper. But any violence is surely to be asymmetrical, as it has always been. The Pastoral Land Commission, operated by Brazil’s Catholic Church, has recorded more than 600 land-related murders in the country since 2003, most in the Amazon region, with a 20 percent increase in 2018. Most victims are Indigenous and other traditional forest dwellers, killed organizing to protect land from illegal extractive activity.

At the edge of Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau territory, where the forest meets barren cattle lands, is a difference of night and day. Without vegetation, the region’s topsoil dries and depletes quickly, requiring expensive systems of short-term life support and the constant creation of new land. Most pasture is degraded and abandoned within 10 or 15 years.

Photo: Gabriel Uchida

We were an hour into the resumed patrol when we walked into it — the place where the forest stops and the agribusiness frontier begins. The frontier not as a metaphor, or a concept in a U.N. report, but as a physical thing that can be seen, touched, stepped across. Abruptly the cool shadow world of closed canopy forest gave way to the blinding oven-hot world of open grassland baking under the midday equatorial sun. On one side of the split screen, the primordial tangle of what the 19th-century Brazilian historian Euclides da Cunha called “the last unwritten page of Genesis.” On the other, a group of humped zebu cows dumbly chewed their cud. Awapu pointed at the only distinct vegetation on the cow’s side of the line, a spiky forage grass that grew in bunches. “That’s capim,” he said. “That’s what the cows eat.” Then he waved his finger across the distant horizon of pasture. “That was all forest when I was young.”

It was here that we made a picnic of crackers and dried fish, on the line between Genesis and Revelation. As we packed up for the hike back to the river, Djurip, the quietest of the three, spoke for the first time. “The whites have never respected our culture because it’s not a money culture, not an agribusiness culture,” he said. “They say we are greedy and ask for too much land. But the whites are the ones with an endless appetite. They are the ones who are devouring everything.”

Francisco "Chico" Mendes, an internationally acclaimed ecologist and advocate of the preserevation of the Amazon Jungle was shot and killed; by unidentifed gunmen at his home in the remote Amazon jungle in December 1988. This is a Feb.1988 photo. (AP Photo)

Brazilian environmentalist Francisco “Chico” Mendes in February 1988.

Photo: AP

4The Ghost of Chico Mendes

When the southwest Amazon was being devoured without check in the 1970s, the forest produced an antibody. A social and political movement coalesced to reject the false choice between conservation and development. Uniting Indigenous and non-Indigenous forest peoples, it spoke the modern language of justice, something new in the Amazon. Its leader was a rubber tapper and union leader from southern Acre named Chico Mendes. As the fires from Rondônia roared west, Mendes organized a coalition of people who depended on a living forest. This coalition pioneered a form of nonviolent direct action called the empate, or stalemate. In some empates, men, women, and children formed human walls around trees, daring the cut crews, their fellow poor, to kill them. In others, armed groups would overwhelm the clearcutters’ camps and hold the workers hostage while smashing chainsaws and decommissioning tractors. The journalist Andrew Revkin witnessed one such empate in which Mendes’s men lectured their captives on ecology and Marxist theory as they prepared to torch the camp.

Mendes had earned the mantle “Gandhi of the Amazon” before his assassination in 1988. His renown peaked just as the world began acknowledging the challenged posed by climate change, a development that timed with Brazil’s transition to civilian rule. Because of this lucky confluence of history, Mendes’s legacy survived in the new constitution and government, most notably in the creation of an archipelago of large “extractive reserves” set aside for the harvesting of rubber, nuts, berries, and other sustainable forest industries. In 2007, when then-President Lula da Silva established a conservation institute inside the Ministry of Environment, he named it after Mendes, his fellow unionist and comrade from the early 1980s.

Luiz Inácio da Silva, now the President of Brazil, delivers speech during funeral of Chico Mendes, environmentalist killed in his hometown of Xapuri. The funeral was held by Bishop Moacir Grenchi at Nossa Senhora de Nazaré Cathedral, in Rio Branco, Acre state, northern Brazil, December 25, 1988. Mendes was murdered by farmers Darly Alves da Silva e Darcy Alves da Silva, who were sentenced to 19 years in prison. Darly escaped in 1993, was recaptured in 1996 and was sentenced to another 2 year and 8 months of incarceration - Photo: Ricardo Chaves /Agência Estado/AE (Agencia Estado via AP Images)

Luiz Inácio da Silva delivers a speech during the funeral of Chico Mendes on Dec. 25, 1988.

Photo: Ricardo Chaves/Agência Estado via AP

Mendes’s name is a curse to the Bolsonaro government but one with the power to rankle. When challenged by a reporter on his disemboweling of the agency bearing Mendes’s name, Environment Minister Salles hissed, “What difference does it make who Chico Mendes is at the moment?” This sentiment extends to Mendes’s heavily forested home state in the western Amazon, Acre, which in October elected a second-generation soy baron, Gladson Cameli, to the governor’s office once occupied by Mendes’s political adviser, the forest ecologist Jorge Viana. Cameli celebrated his election by meeting with agribusiness executives in Porto Velho, where he announced, “The economic salvation of Acre is agribusiness. Rondônia, our neighbor and brother, is the proof.”

Even on the Chico Mendes Reservation on Acre’s southern borders with Peru and Bolivia, the children and grandchildren of the empate generation — who grew up on stories of monkey-wrenching tractors and sending villainous cattle barons packing — are turning to ranching. The reservation is reported to hold more than 30,000 heads of cattle on cleared land, including many herds well above the legal limit imposed on protected areas.

In the long term, Mendes’s vision remains valid: A self-renewing forest bursting with flora and fauna will ultimately pay greater dividends, economic and environmental, than the creation of a semiarid savannah dotted with cows whose expansion is premised on creating the conditions that will ultimately cause drought. But that truth is not swaying families abandoned to the vicissitudes of a global market that prizes hardwoods and hamburgers. “Cattle is a secure market. You can get a good income selling a calf, an ox,” a Mendes Reserve resident told ProPublica reporter Lisa Song in her recent investigation into the failure of international efforts to encourage and buffer sustainable forest economies.

A self-renewing forest bursting with flora and fauna will ultimately pay greater dividends, economic and environmental, than the creation of a semiarid savannah dotted with cows.

In the Acre assembly, a minority bloc of deputies is working to modernize Mendes’s vision and stop another arc of fire from devouring the state’s largely intact forests. At their head is Jenilson Leite, a 41-year-old Indigenous physician and vice president of the state legislature. I met Leite one night in a conference room at the capital building in Rio Branco. Bespectacled and wearing a sharp navy-blue suit, the politician chose his words carefully and with an intensity that belied his boyish looks.

“After the dictatorship, Acre invested in rural communities and conservation, making us more dependent on federal resources. And by some metrics, we and other forested areas appear ‘unproductive,’” said Leite. “I’m not saying the forest is untouchable, but cutting it is not the answer. If we put value on Acre’s Indigenous groups and others who manage forest resources sustainably, they’ll put more into the economy than expanding cattle and soy. The medicinal potential of the healthy forest is enormous. Let’s build research labs. Ecotourism. Sustainable food industries that don’t require annual planting. Açaí, Brazil nuts, fruits.”

The biological riches of the Amazon are made possible by the nutrients provided by the constant decomposition of its bountiful vegetation, not the thin layers of soil beneath the forest floor. Take away this vegetation, and the region’s topsoil dries and depletes quickly, requiring expensive systems of short-term life support and the constant creation of new land. Most pasture is degraded and abandoned within 10 or 15 years, meaning the industry’s existence (never mind its expansion) is predicated on a permanent cycle of destruction: More forest must always be cut to keep ahead of the processes triggered by the last cutting, which removed the soil’s natural source of nutrients. The Amazon’s soy industry likewise struggles to keep pace with rapidly fading soils by creating land and saturating it with ever larger dosages of chemical fertilizers and pesticides. (Bolsonaro’s minister of agriculture, the ruralista Tereza Cristina, has earned the nickname “Muse of Poison” for her dedication to ending restrictions on the most toxic pesticides.)

A view of Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau land in Rondônia on Sept. 24, 2016. Around 400 ethnic groups across the Amazonian basin envision a “sacred corridor of life” of contiguous Indigenous territories reaching from the Andes to the Atlantic, which would constitute a 500-million-acre stretch of rainforest.

Photo: Gabriel Uchida

Meanwhile, most of the jobs created are short-term: cutting down trees.

Joaquim Francisco de Carvalho, a former chief of Brazil’s Institute of Forest Development, estimates that one hectare of livestock or soy is worth between $25 and $250, while the same hectare of sustainably managed forest can yield as much as $850. But the most important difference is one that can’t be quantified. The latter approach preserves the Amazon’s biodiversity and what the ethnobotanist and anthropologist Wade Davis calls its “ethnosphere” — the last remaining cultures that hold a worldview and values fundamentally different from those that brought us the Anthropocene epoch. The rainforest’s original inhabitants are its most effective defenders precisely because they don’t see it as a repository of resources to be extracted and sold, whether it be gold, lumber, or carbon credits.

This is not the same as saying the language of trade and development is foreign to the rainforest. Aside from a dwindling number of uncontacted tribes and those living in voluntary isolation, Indigenous groups want development and links to the world. Marcos Apurinã, for instance, is trying to revive Chico Mendes’s Forest Peoples Alliance, which united Brazil’s Indigenous with the quilombolas (forest communities established by runaway slaves) and other groups of traditional small-scale extractivists.

“We have our differences, but we share a common enemy in agribusiness and the ruralistas,” he told me. “We need a triple alliance on the front lines unified behind a plan to defend the region and develop it in our own way. We also need Brazil’s courts. The international courts. The NGOs.”

Marcos was a founding member of the National Committee of Indigenous Policy, a consultative body established in 2015 to connect Indigenous groups and federal agencies handling development and sustainability policy. “We have alternative development ideas to generate the money we need to live in the modern world,” he said. “We’ve given those ideas to the government. Like everything else, the process froze when Bolsonaro was elected. We don’t know what will happen.”

A port in Boca do Acre, Brazil.

Photo: Mauro Toledo Rodrigues

The drive north from Acre into Amazonas on B.R. 317 resembles the drive through Rondônia on B.R. 364: a monotonous run of pastureland, with brief forest interludes wherever the road cuts through an Indigenous territory. The pasture ends where 317 terminates, at Boca do Acre, a tidy and growing frontier town of 35,000 people at the lip of the world’s most massive remaining block of rainforest. The ascendant ranching capital of south Amazonas, Boca swaggers with the ersatz Texas style found throughout western Brazil, with cowboy-themed bars and burly men dressed in the region’s take on the Marlboro Man: unbuttoned checkered shirt, cross on a gold chain, blue jeans, oversized belt buckle, boots, and a wide-brimmed hat of straw or leather, pulled low.

On my first morning in Boca, I made an unannounced visit to the home of Dilermando Melo de Lima, a local ranching grandee and president of the Rural Syndicate of Boca do Acre. A potbellied 72-year-old with an unexpected cauliflower nose, he was sitting on his porch drinking coffee, with a cat at his feet. He welcomed the chance to talk cattle and was bullish on the industry’s prospects. “Understand,” he said, “from Rondônia, across Acre and into Amazonas, the future is ranching, for the simple reason that it has the best conditions for meat ranching in the Amazon.”

When I asked his thoughts on the concerns of Indigenous groups, and others, that allowing the agricultural frontier to move further into the Amazon endangered the natural systems that make ranching and agriculture possible, he gently waved me off.

“The forest is going to be cut anyway. The military regime was good for development. Bolsonaro has the same ideas, and ranchers are betting everything on his success.”

“We ranchers face many difficulties,” he said. “There are too many restrictions and laws. Too many protected areas. The Camicuã territory near here is 46,000 square hectares of intact land. And we can’t touch it! They should give us the permits. The forest is going to be cut anyway. The military regime was good for development. Bolsonaro has the same ideas, and ranchers are betting everything on his success.”

The old rancher relaxed a bit when the conversation drifted from politics. The son of a farmer who’d migrated to the region in the 1930s, his voice softened as he described the sleepy fishing and trading village of his boyhood, before cows followed the penetrator roads north and morning breezes smelled of the slaughterhouse. Remembering that place long gone, he sounded less like a cattleman than an Indian in one of the forested Indigenous atolls along highway 317. “It was all forest and rivers back then,” he said. “From here all the way down to Rio Branco, forest and rivers.”

The true value of forest, like this section of Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau territory, cannot be quantified, and its Indigenous inhabitants don’t see it as a repository of resources — whether it be gold, lumber, or carbon credits — to be extracted and sold.

Photo: Gabriel Uchida

5The Brink

In early May, a few weeks after Melo de Lima boasted to me about ranching’s expansion into Amazonas, the United Nations disturbed the world with the findings of a landmark report on biodiversity. Produced by experts across dozens of disciplines, it concluded that only “transformative change” could prevent the looming extinction of one million plant and animal species. These million coal-mine canaries, dropping to the floors of degraded and fragmented rainforests, and floating to the surfaces of overfished and acidifying oceans, foretold a wider disintegration in the web of life that threatens the “very foundations of our economies, livelihoods, food security, health and quality of life worldwide.”

The call for “transformative change” was no echo of familiar appeals to somehow “green” the endless growth that is programmed into the genes of industrial-consumer civilization. “We mean a fundamental, system-wide reorganization across technological, economic and social factors, including paradigms, goals and values,” said Robert Watson, the British atmospheric chemist who chaired the U.N. panel. As for where humanity should look for help and inspiration during this difficult civilizational pivot, the report urges the “full and effective participation of Indigenous Peoples” in developing systems of environmental governance informed by their “knowledge, innovations and practices, institutions and values.”

The rainforest in Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau territory on April 22, 2019. Indigenous leaders are promoting alternatives to clear-cutting, such as medical research, ecotourism, and sustainable food industries like açaí, Brazil nuts, and fruit.

Photo: Gabriel Uchida

This is the fruit of a delayed but deepening dialogue between occidental science and Indigenous cultures. After decades of watching from the margins, Indigenous groups have moved close to the center of the ring at global environmental and conservation summits, in tandem with a wave of research that backs up their historical claims to being the forest’s most natural and effective protectors. Last November, an Amazonian delegation delivered a document — the “Bogota Declaration” — to the 14th U.N. Biodiversity Conference held in the Egyptian coastal city of Sharm el-Sheikh. It outlined a plan, devised by 400 ethic groups across the basin, to establish a “sacred corridor of life” of contiguous Indigenous territories reaching from the Andes to the Atlantic. Inside this 500-million-acre stretch of rainforest, Indigenous nations would pool their ancestral knowledge and showcase alternative modes of development and ways of living. The declaration described the proposal as “a first step to guaranteeing the existence of all forms of life on the Planet.”

Notably, the signatories seek international support and recognition, a challenge to the sovereignty of the Amazonian governments currently dividing up the rainforest into a grid of mining, logging, oil, and agribusiness concessions. For the Bolsonaro administration, the prospect of Indigenous groups allying with Western governments and the U.N. under a banner of climate emergency only validates centuries of nationalist paranoia. Though the anxiety is misplaced, and the prospects of an internationally protected rainforest remote, the Bogota Declaration does frame the future of the Amazon as it must be framed, not as an economic matter or a morality play pitting cowboys against Indians, but as a global crisis demanding new ways of seeing the world and all that is in it.

Mauro Toledo Rodrigues contributed reporting.

https://theintercept.com/2019/07/06/bra ... -ranching/

Jair Bolsonaro accuses NGOs of setting fires in Amazon rainforest

Brazilian president blames green groups for rise in blazes, but offers no evidence for claim

Jonathan Watts @jonathanwatts Wed 21 Aug 2019 18.11 BST Last modified on Wed 21 Aug 2019 20.40 BST

The Brazilian president, Jair Bolsonaro, has accused environmental groups of setting fires in the Amazon as he tries to deflect growing international criticism of his failure to protect the world’s biggest rainforest.

A surge of fires in several Amazonian states this month followed reports that farmers were feeling emboldened to clear land for crop fields and cattle ranches because the new Brazilian government was keen to open up the region to economic activity.

Brazil has had more than 72,000 fire outbreaks so far this year, an 84% increase on the same period in 2018, according to the country’s National Institute for Space Research. More than half of them were in the Amazon.

There was a sharp spike in deforestation during July, which has been followed by extensive burning in August. Local newspapers say farmers in some regions are organising “fire days” to take advantage of weaker enforcement by the authorities.

Since Bolsonaro took power the environment agency has issued fewer penalties, and ministers have made clear that their sympathies are with loggers rather than the indigenous groups who live in the forest. The head of Brazil’s space agency was fired last month after the president disputed the official deforestation data from satellites.

An international outcry has prompted Norway and Germany to halt donations to Brazil’s Amazon fund, which supports many environmental NGOs as well as government agencies. There have also been calls for Europe to block a trade deal with Brazil and other South American nations.

Bolsonaro suggested the fires were started by environmental NGOs to embarrass his government.

“On the question of burning in the Amazon, which in my opinion may have been initiated by NGOs because they lost money, what is the intention? To bring problems to Brazil,” the president told a steel industry congress in Brasilia.

He made a similar allegation earlier in the day when he suggested groups had gone out with cameras and started fires so they could film them. Asked whether he had evidence, or whether he could name the NGOs involved, Bolsonaro said there were no written records and it was just his feeling.

Environmental activists said his comments were an absurd attempt to deflect attention from the problem of poor oversight and tacit encouragement of illegal forest clearance. “Those who destroy the Amazon and let deforestation continue unabated are encouraged by the Bolsonaro government’s actions and policies. Since taking office, the current government has been systematically dismantling Brazil’s environmental policy,” said Danicley Aguiar, of Greenpeace Brazil.

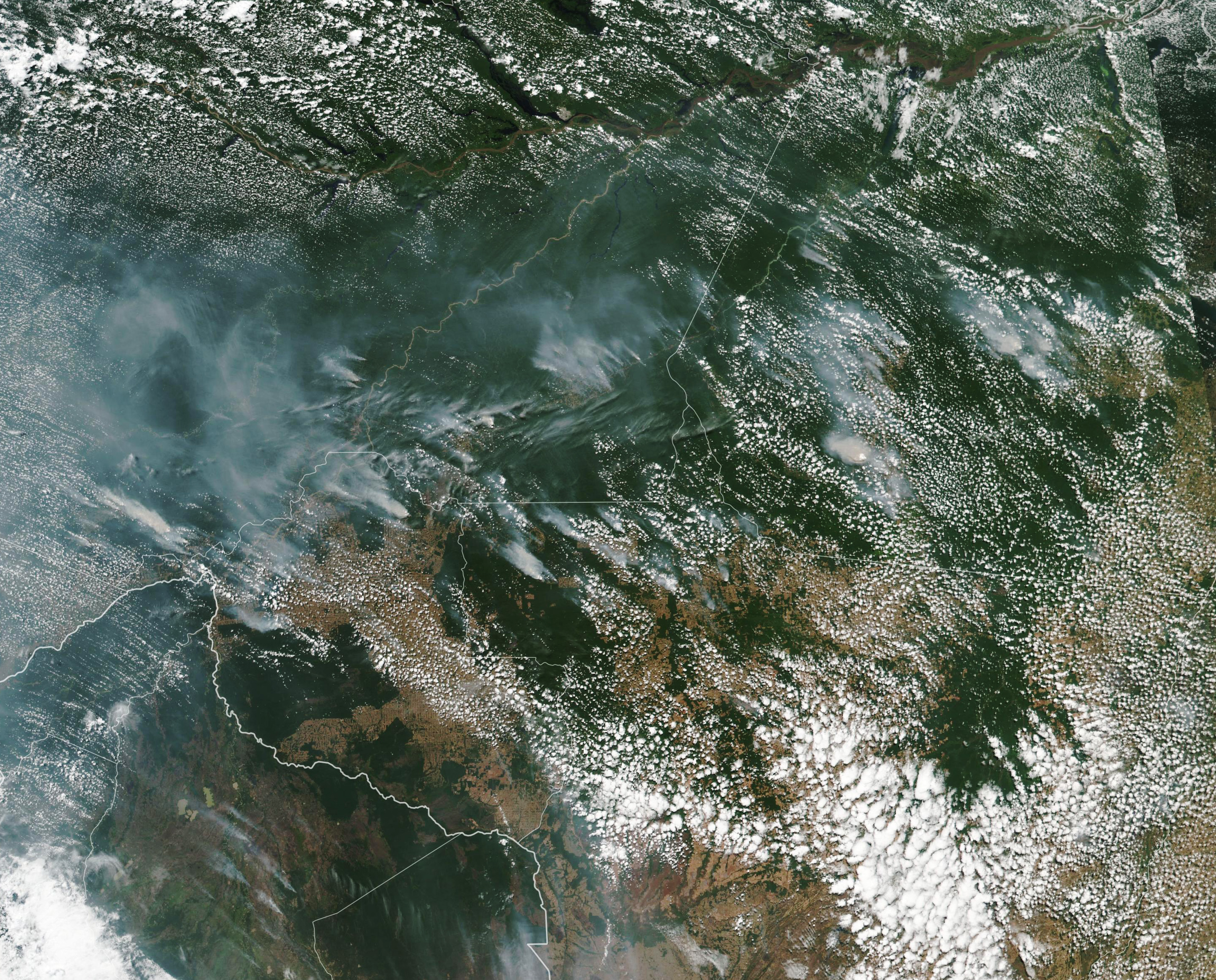

In Brazil’s Amazonas state, heat from forest fires has been above average every day this month, according to data provided to the Guardian by the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service. On the peak day, 15 August, the energy released into the atmosphere from this state was about 700% higher than the average for this date over the previous 15 years. The story was similar in Rondônia state, where there have been 10 days this month where fire heat has been more than double the average for the time of year.

It is unclear which fires have been deliberately set by farmers to clear land and which were accidental or natural. The problem is not restricted to Brazil. Neighbouring Bolivia is also experiencing unusually large wildfires that have reportedly destroyed 5,180 sq km (2,000 sq miles) of forest. Video from the country’s Santa Cruz department shows monkeys and other animals scurrying in search of shelter amid a landscape reduced to blackened stumps, bare branches and ashes. Copernicus satellite images show it was primarily a fire in Bolivia that led to the darkening of the skies during the day on Monday in São Paulo, thousands of miles away.

82_28 » Tue Aug 20, 2019 10:34 pm wrote:I can report that amazonia is doing just fine according to my eyewitness travels today in Seattle. Which reminds me of this old job I had, I would get shipments of shit with little packing bags of air and I would ask customers if they would like to buy a bag of air. Furthermore, Bezos has enough money. Fucking buy the forest, save it and then give free tix for people to check out your jungle like spheres downtown.

DEMOCRACIAABIERTA

Leaked documents show Brazil’s Bolsonaro has grave plans for Amazon rainforest

democraciaAbierta has seen a PowerPoint presentation that shows that Bolsonaro’s government intends to use hate speech to isolate minorities of the Amazon. Español Português

Manuella Libardi

21 August 2019

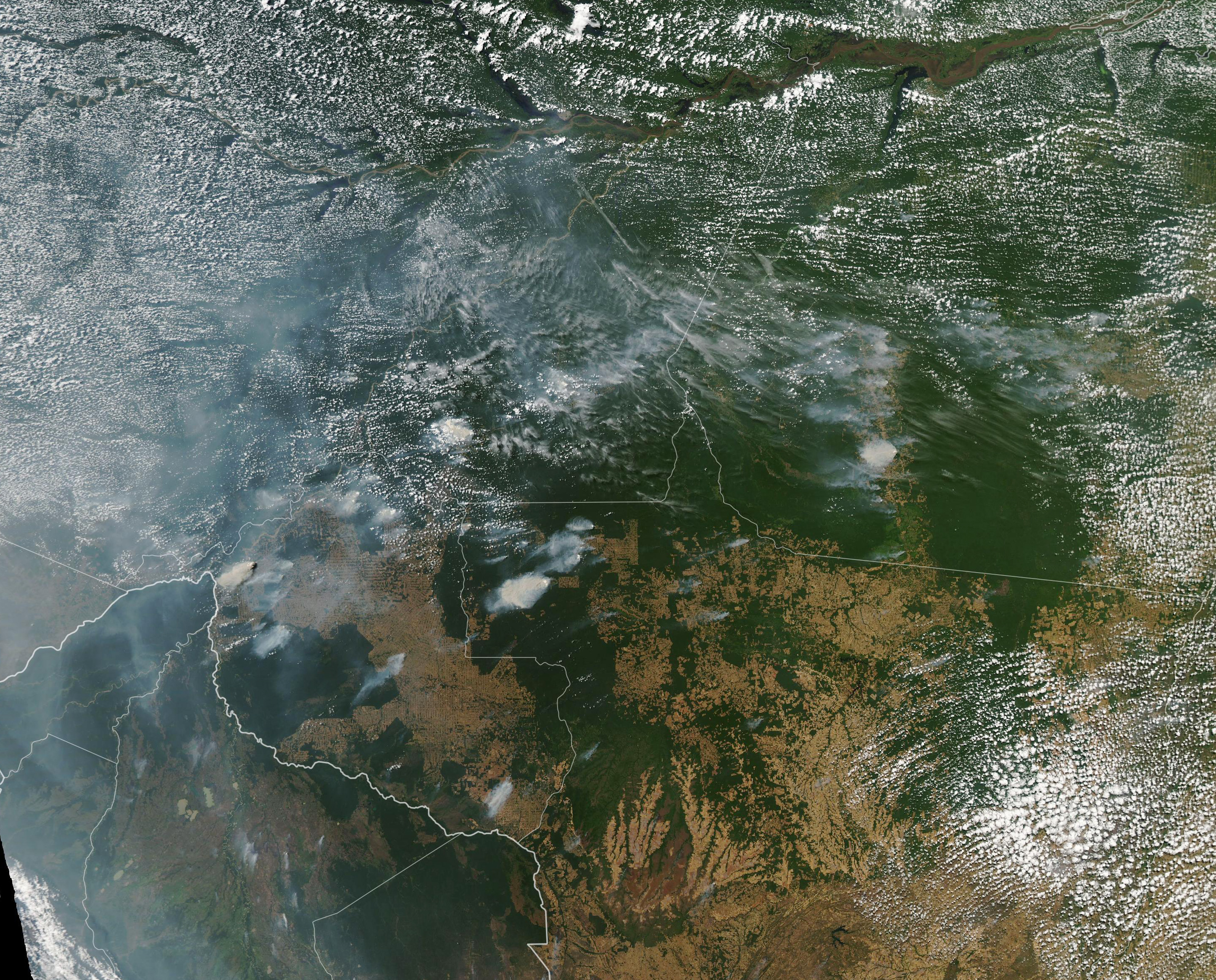

Wildfires have raging through the Amazon rainforest for weeks. Satellite data show an 84% increase of fire outbreaks on the same period in 2018. | Pixabay

Leaked documents show that Jair Bolsonaro's government intends to use the Brazilian president's hate speech to isolate minorities living in the Amazon region. The PowerPoint slides, which democraciaAbierta has seen, also reveal plans to implement predatory projects that could have a devastating environmental impact.

The Bolsonaro government has as one of its priorities to strategically occupy the Amazon region to prevent the implementation of multilateral conservation projects for the rainforest, specifically the so-called “Triple A” project.

"Development projects must be implemented on the Amazon basin to integrate it into the rest of the national territory in order to fight off international pressure for the implementation of the so-called 'Triple A' project. To do this, it is necessary to build the Trombetas River hydroelectric plant, the Óbidos bridge over the Amazon River, and the implementation of the BR-163 highway to the border with Suriname," one of slides read.

One of the tactics cited in the document is to redefine the paradigms of indigenism, quilombolism and environmentalism through the lenses of liberalism and conservatism

One of the slides from the presentation. | democraciaAbierta

In February, ministers Gustavo Bebianno (Secretary-General of the Presidency), Ricardo Salles (Environment) and Damares Alves (Women, Family and Human Rights) traveled to Tiriós (Pará) to speak with local leaders about the construction of a bridge over the Amazon River in the city of Óbidos, a hydroelectric plant in Oriximiná, and the expansion of the BR-163 highway to the Suriname border.

During the meeting, the ministers used a PowerPoint presentation that detailed the projects announced by the Bolsonaro government for the region. The presentation, which was leaked to democraciaAbierta, argues that a strong government presence in the Amazon region is important to prevent any conservation projects from taking roots.

The slides are clear. Before any predatory plan is implemented, the strategy begins with rhetoric. Bolsonaro's hate speech already shows that the plan is working. The Amazon is on fire. It's been burning for weeks and not even those who live in Brazil were fully aware. Thanks to the efforts of local communities with the help of social networks, the reality is finally going viral.

The online reaction is far from being sensationalist. This year alone, Brazil had 72,000 fire outbreaks, half of which are in the Amazon. The National Institute for Space Research (Inpe) reported that its satellite data showed an 84% increase on the same period in 2018.

Attacking non-governmental organizations is part of the Bolsonaro government's strategy. According to another of the PowerPoint's slide, the country is currently facing a globalist campaign that "relativizes the National Sovereignty in the Amazon Basin," using a combination of international pressure and also what the government called "psychological oppression" both externally and internally.

This campaign mobilizes environmental and indigenous rights organizations, as well as the media, to exert diplomatic and economic pressure on Brazilian institutions. The conspiracy also encourages minorities – mainly indigenous and quilombola (residents of settlements founded by people of African origin who escaped slavery) – to act with the support of public institutions at the federal, state and municipal levels. The result of this movement, they say in the presentation, restricts "the government's freedom of action".

Item 3 of the document points out that the seeks to fight off "international pressures" for the implementation of a conservation projects known as Triple A. | democraciaAbierta

Those are, according to a slide, "the new hopes for the Homeland: Brazil above everything!"

So it is unsurprising that Bolsonaro's response to the fires comes in the form of an attack on NGOs. On Wednesday, August 21, Bolsonaro said he believed non-governmental organizations could be behind the fires as a tactic "to draw attention against me, against the government of Brazil.".

Bolsonaro did not cite names of NGOs and, when asked if he has evidence to support the allegations, he said there were no written records of the suspicions. According to the president, NGOs may be retaliating against his government's budget cuts. His government cut 40 percent of international transfers to NGOs, he added.

Part of the government's strategy of circumventing this globalist campaign is to depreciate the relevance and voices of minorities that live in the region, transforming them into enemies. One of the tactics cited in the document is to redefine the paradigms of indigenism, quilombolism and environmentalism through the lenses of liberalism and conservatism, based on realist theories. Those are, according to a slide, "the new hopes for the Homeland: Brazil above everything!"

https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/democr ... ainforest/

Harvey » Fri Aug 23, 2019 3:25 am wrote:82_28 » Tue Aug 20, 2019 10:34 pm wrote:I can report that amazonia is doing just fine according to my eyewitness travels today in Seattle. Which reminds me of this old job I had, I would get shipments of shit with little packing bags of air and I would ask customers if they would like to buy a bag of air. Furthermore, Bezos has enough money. Fucking buy the forest, save it and then give free tix for people to check out your jungle like spheres downtown.

Like many others I'm sick at heart. I expected this the day Bolsonaro was 'elected' but I hoped it wouldn't happen. One of the ways I'd hoped it might not was that all those 'men of vision' we're encouraged to admire or hate, from George Soros to Warren Buffet, Bill Gates to Elon Musk, all of those who made their billions then forgot their reason, might join together in paying countries like Brazil, (Bolivia, Ecuador, Venezuela...) more to keep their remaining forests intact than they were worth as plantations or as mines, even enlarge them while urging governments to back them in doing so. And perhaps tie some of the proceeds to social and development projects. It wasn't to be. They had no vision.

I think the light has gone out. I think we blew our last chance.

The Amazon is burning at record rates—and deforestation is to blame

The blazes are so huge that smoke can be seen from space, and experts say the fires could have major climate impacts.

By Sarah Gibbens PUBLISHED August 21, 2019

Wildfires are currently burning so intensely in the Amazon rainforest that smoke from the blaze has covered nearby cities in a dark haze.

Multiple news outlets are reporting that Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research (INPE) reported a record 72,843 fires this year, an 80 percent increase from last year. More than 9,000 of those fires have been spotted in the past week.

The size of the fires is still unclear, but they spread over several large Amazon states in northwest Brazil. On August 11, NASA noted that the fires were large enough that they could be spotted from space.

“This is without any question one of only two times that there have been fires like this,” in the Amazon, says Thomas Lovejoy, an ecologist and National Geographic Explorer-at-Large.

“There’s no question that it’s a consequence of the recent uptick in deforestation,“ he says.

How is this related to Brazil’s pro-business environmental policies?

Environmentalists have been raising the alarm about deforestation since the country’s current president Jair Bolsonaro was elected in 2018. A major part of his campaign message called for opening up the Amazon for business, and since he’s been in power, he’s done just that.

Data released by INPE earlier this month indicated that more forest has been cleared in Brazil this summer alone than in the last three years combined.

“In the previous years [wildfires] were very much related to the lack of rain, but it has been quite moist this year,” says Adriane Muelbert, an ecologist who’s studied how Amazon deforestation plays a role in climate change.

“That leads us to think that this is deforestation-driven fire,” she says.

In addition to harvesting timber, many trees in the Amazon are cleared to plant soy or make way for lucrative cattle pastures. Burning is commonly used to clear trees quickly. Like the wildfires that plague California, most are started by humans, but then spiral out of control.

Lovejoy describes a cyclical system in which deforestation fuels forest loss, making the region drier, spurring even more deforestation. Much of the rain in the Amazon is generated by the rainforest itself, but as trees disappear, rainfall declines. Experts worry that this downward spiral could increasingly dry out the forest and push it to a point of no return, where it more resembles savannah than rainforest.

“The Amazon has this tipping point because it makes half of its own rainfall,” says Lovejoy. That’s why, he says, “the Amazon has to be managed as a system.”

What do these fires have to do with climate change?

If deforestation and mismanaged forest clearing by fire continues, Lovejoy and Muelbert warn that wildfires of this scale could continue. Such a massive loss of forest would be felt on a global scale.

Protecting the Amazon is often touted as one of the most effective ways to mitigate the effect of climate change. The ecosystem absorbs millions of tons of carbon emissions every year. When those trees are cut or burned, they not only release the carbon they were storing, but a tool to absorb carbon emissions disappears.

“Any forest destroyed is a threat to biodiversity and the people who use that biodiversity," says Lovejoy. He adds that "the overwhelming threat is that a lot of carbon goes into the atmosphere."

Muelbert says it’s too early to calculate how much carbon might be emitted by this August’s wildfires. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released a report earlier this month saying the world doesn’t have forest to spare if it wants to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

“It’s a tragedy,” Muelbert says of the wildfires, and of the deforestation behind it. She says: “a crime against the planet, and a crime against humankind.”

They had no vision.

Users browsing this forum: No registered users and 6 guests