Dismissed as fakes for a century, enigmatic Puerto Rican stones could rewrite history

BY JIM WYSS

OCTOBER 07, 2019 06:00 AM, UPDATED OCTOBER 07, 2019 06:00 AM

Unmute

Loaded: 99.91%

Captions

Fullscreen

PlayCurrent Time 0:20

/

Duration 1:23SKip Back

Skip Forward

New research suggest Puerto Rico's 'Father Nazario Stones' are real

SHARE

For more than a century, Puerto Rico’s “Father Nazario Stones” have been considered frauds designed to dupe collectors of antiquities. Now, new research by archeologists from Puerto Rico, Washington and Israel suggest the etched stones are real. BY JIM WYSS

UTUADO, PUERTO RICO

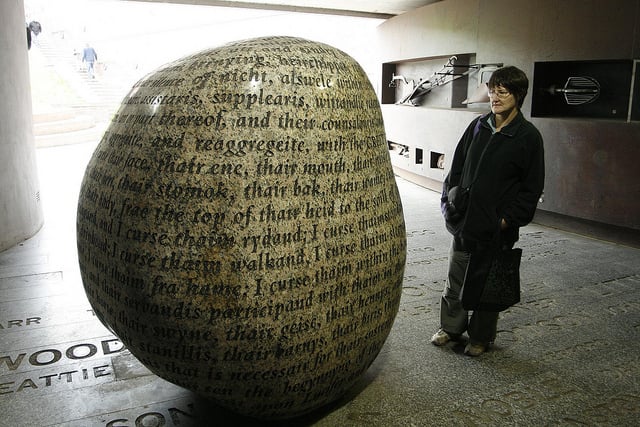

For more than a century, the fist-sized rocks etched with enigmatic patterns were ignored by academics and shunned by cultural power brokers.

Discovered in Puerto Rico in the 1880s by a priest who was convinced they were a link to one of the Lost Tribes of Israel, the stones were declared forgeries in the early 1900s by researchers from the Smithsonian Institution.

And so the rocks languished — literally collecting dust.

TOP ARTICLES

She was ‘held hostage by a pimp’ and forced to work as

hooker in South Beach, cops say

When Puerto Rican archaeologist Reniel Rodríguez Ramos first stumbled onto the collection in 2001, the artifacts were so unappreciated that one was being used as a doorstop

“These stones were considered garbage,” Rodríguez recalls. “They were getting no love from any institution or even any archaeologist in Puerto Rico.”

But now the rocks, known as Las Piedras del Padre Nazario, or Father Nazario’s Stones, are undergoing a radical reevaluation. Not only is there growing evidence that they’re genuine antiquities, there are also clues that they might represent a lost language — a finding that could rewrite the island’s pre-Columbian history.

Standing in his cramped lab at the University of Puerto Rico’s Utuado Campus, Rodríguez puts one of the stones under a magnifying glass and describes the figure he sees chiseled into its surface. It seems to be the profile of a man wearing something akin to a turban. Lines curving around the stone’s surface are pocked with small symbols.

DSC_0213 (2).JPG

Reniel Rodríguez Ramos, an archaeologist at the University of Puerto Rico’s Utuado Campus, holds one of the “Father Nazario Stones” he’s been studying. Jim Wyss

JWYSS@MIAMIHERALD.COMRodríguez has identified about 20 symbols that repeat across the more than 300 stones he’s studied. Initially, he thought the angles and sloping lines might be astronomical information, a guide to the cosmos.

“It’s a system of annotation, not a decoration,” Rodríguez said, cradling a stone. “Is it a commercial or spiritual annotation? Is it a registry of names? We don’t know yet … but it’s something revolutionary in the Americas.”

Read Next

AMERICAS

Did a historian from Ecuador find the lost ‘treasure’ of the Incas — in a book?

MARCH 02, 2017 7:00 AM

Puerto Rico’s original inhabitants, the Tainos, left the English language a colorful array of words, including “caiman,” “barbecue,” “papaya” and “hurricane.” And the island is scattered with carved stones known as petroglyphs. But there were no traces of a written language as such.

The Padre Nazario stones could change that — if the larger scientific community agrees with Rodríguez that they’re real.

The story of why the stones have been written off as fakes goes back to the early 1900s and a man named Jesse Walter Fewkes. Born in Massachusetts in 1850, Fewkes was a Harvard-trained zoologist who developed a love for archaeology and anthropology.

After the United States annexed Puerto Rico from the Spanish in 1898, the Bureau of American Ethnology commissioned Fewkes to study this new American acquisition. He started traveling the island in 1902, branching out to Haiti, Cuba and Trinidad as he tried to understand the Arawakan cultures that lived there before Columbus’ arrival in 1492.

43313083-73ED-4935-AB70-26ABBD6A107A.jpeg

DSC_0234 (2).JPG

Reniel Rodríguez Ramos, an archaeologist at the University of Puerto Rico’s Utuado Campus, holds one of the “Father Nazario Stones” he’s been studying. Jim Wyss

JWYSS@MIAMIHERALD.COMOn one of those expeditions, Fewkes met José María Nazario, a priest and amateur archaeologist from Guayanilla on Puerto Rico’s southern coast. Nazario had collected about 800 of the “enigmatical” stones from the mountains of western Puerto Rico and Fewkes tried to buy them for the National Museum. His offer was rebuffed, but six stones ended up at the Smithsonian Institution and are now stored in the “Fake” collection.

“Padre Nazario considers that these hieroglyphics belong to the ancient writing possessed by the prehistoric Porto Ricans,” a label for one of the stones at the Smithsonian reads. “In [Nazario’s] collection there are several bureaus full of stone [objects] inscribed like this. He also has a stone slab covered with these figures … believed by Doctor Fewkes to be a fraud.”

Fewkes’ judgment — powerful and definitive — shut down further research into the stones. And in academic circles the prevailing theory was that Puerto Rican locals in the late 1800s had made the fake antiquities to dupe the Spanish priest.

Rodríguez said the rocks were never even mentioned when he was an archaeology student. And while local naturalists and historians have written about the artifacts, “there has not been a single page written by an archaeologist about these stones, and they’ve been around for 140 years,” Rodríguez said.

The dark cloud left by Fewkes persists. When Rodríguez started to seriously study the stones again in 2011, his friends warned him he was committing “academic suicide.”

Rodríguez pushed ahead anyway. “My aspiration is not to teach at Harvard. I’m here in Utuado and that’s all I care about,” he said.

DSC_0200 (2).JPG

Reniel Rodríguez Ramos, an archaeologist at the University of Puerto Rico’s Utuado Campus, has been studying the “Father Nazario Stones.” The rocks, etched with symbols, have been considered forgeries for more than a century. Now Rodríguez says there’s growing evidence that they’re real. Jim Wyss

JWYSS@MIAMIHERALD.COMThe decades of neglect had also taken their toll on the stones. Of the 800 that were originally in Nazario’s possession, only about 330 remain. Most are in Puerto Rico, including at an archaeology museum in Guayanilla, but some are at Harvard’s Peabody Museum, where they’re also in the fake collection, and others are at the Quai Branly Museum in Paris.

When Rodríguez approached a fellow researcher, Christopher Rollston, about the stones, Rollston was fully aware of their reputation. A professor of Hebrew, Phoenician and Aramaic at George Washington University, Rollston has made a career out of spotting forged antiquities.

“I’ve debunked a lot of scriptural forgeries over the past couple of decades,” Rollston said in a telephone interview. “And a lot of people believed these were modern forgeries from the late 1800s.”

Rollston traveled to Puerto Rico earlier this year to study the stones. In the diagonal lines that Rodríguez first interpreted as astronomical angles, or perhaps representations of mummy-like wrappings, Rollston saw “register lines” — like the lines of a ruled sheet of paper. And below and above those lines were a series of symbols that repeated across the stones.

While Rodríguez has identified about 20 separate symbols, Rollston said there aren’t enough to think of it as an alphabet or even a complex non-alphabetic writing system.

“My sense is that these [symbols] are not Mesoamerican writing — they’re not Aztec or Mayan — they’re definitely not that,” he said. “And yet I don’t believe they are forgeries from the late 1800s either. These seem to represent a fledgling writing system that is different than the writing systems that we know.”

In his report, Rollston posits that those “attempting to write upon these stones” perhaps knew about or had seen written language, “but for some reason they did not attempt to replicate the signs or the symbols of that writing system.”

And contrary to what Father Nazario believed, the symbols aren’t Hebrew or Phoenician brought to the New World by one of the Lost Tribes of Israel.

Despite enduring speculation that one of the so-called Lost Tribes might have made their way halfway around the world, Rollston said there is ample evidence in the Bible and from other sources that those tribes, scattered after the fall of the northern kingdom of Israel/Samaria in 722 B.C., never made it out of the ancient Near East.

“From the perspective of scholarship, we’ve known for about 150 years that the tribes of Israel weren’t lost. We know entirely what happened to them,” Rollston said.

Fewkes.png

Jesse Walter Fewkes, an anthropologist with the Bureau of American Ethnology, began visiting Puerto Rico in 1902 to catalog pre-Columbian artifacts and study indigenous culture. After he declared a batch of etched stones frauds, they went unappreciated and unstudied for more than a century. Now there are indications that the “Father Nazario Stones” are real and may provide clues to a lost language. SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION

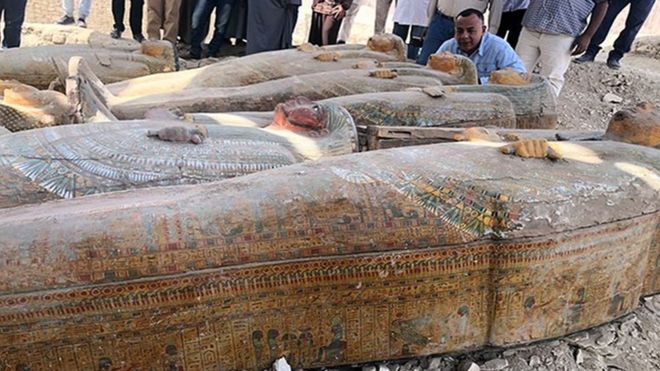

Another key piece of evidence came from the University of Haifa in Israel. Using state-of-the-art microscopes, researchers determined that the “weathering” of the stones — subtle changes due to prolonged exposure to the elements — proved that they had been out in the open for years after they had been engraved. That is, the stones weren’t etched during the era that Father Nazario found them.

In addition, while Fewkes said the stones were carved with “iron instruments” — further proof that they were modern-day forgeries and not stone-age relics — the Israeli researchers cast doubt on that theory. If they had been made with metal instruments, the researchers expected to find microscopic traces of the metal in the grooves. They didn’t.

There’s still a long road for the stones to take their proper place in history. Rodríguez is working on a paper encapsulating the new research which will have to survive the peer-review process.

Read Next

AMERICAS

As Puerto Ricans leave in record numbers, commission unveils plan to overhaul debt

SEPTEMBER 27, 2019 12:21 PM

And even if he convinces the larger scientific community that the stones are real, what they represent remains a mystery.

Rodríguez believes there’s a chance that the stones — or at least their writing — came from some other region or continent. It’s a contentious theory.

Research into pre-Columbian maritime trade routes is usually taken about as seriously as “studies of Bigfoot and ancient aliens,” he said.

“But I think these stones could potentially be the first robust evidence to begin having a discussion about the possibility of pre-nautas,” or pre-Columbian navigators, he said. “But we have to begin seriously studying these stones.”

Used to working in obscurity, Rodríguez has found that the Piedras del Padre Nazario have made him something of a celebrity on an island unaccustomed to good news.

When he gave a conference about the stones in Guayanilla, where some of the stones are on display, more than 400 people attended. The mayor gave him the keys to the city.

Rodríguez said the existence of the stones broadens the island’s sense of history.

“The stones question the meta-narrative that Columbus brought writing and history with him. That’s why they call everything before him pre-history,” he said. “That type of thinking separates us from hundreds and thousands of years of our own history. … It’s not the same to tell a people you have 500 years of history as to tell them your history goes back 6,000 years.”

Reniel Rodríguez Ramos, an archaeologist at the University of Puerto Rico’s Utuado Campus, has been studying the “Father Nazario Stones.” The rocks, etched with symbols, have been considered forgeries for more than a century. Now Rodríguez says there’s growing evidence that they’re real and might hold clues to a previously unknown language. First found in the 1880s, there were originally about 800 stones. Now the whereabouts of only about 330 are known, scattered across the continent and Europe. Reniel Rodríguez Ramos, an archaeologist at the University of Puerto Rico’s Utuado Campus, has been studying the “Father Nazario Stones.” The rocks, etched with symbols, have been considered forgeries for more than a century. Now Rodríguez says there’s growing evidence that they’re real and might hold clues to a previously unknown language. One of the “Father Nazario Stones” in the Smithsonian Institution’s “Fake” collection. Reniel Rodríguez Ramos, an archaeologist at the University of Puerto Rico’s Utuado Campus, has been studying the “Father Nazario Stones.” The rocks, etched with symbols, have been considered forgeries for more than a century. Now Rodríguez says there’s growing evidence that they’re real and might hold clues to a previously unknown language. First found in the 1880s, there were originally about 800 stones. Now the whereabouts of only about 330 are known, scattered across the continent and Europe. Reniel Rodríguez Ramos, an archaeologist at the University of Puerto Rico’s Utuado Campus, has been studying the “Father Nazario Stones.” The rocks, etched with symbols, have been considered forgeries for more than a century. Now Rodríguez says there’s growing evidence that they’re real and might hold clues to a previously unknown language.

1

of 3

Reniel Rodríguez Ramos, an archaeologist at the University of Puerto Rico’s Utuado Campus, has been studying the “Father Nazario Stones.” The rocks, etched with symbols, have been considered forgeries for more than a century. Now Rodríguez says there’s growing evidence that they’re real and might hold clues to a previously unknown language. JIM WYSS

JWYSS@MIAMIHERALD.COMGALLERY

Read more here:

https://www.miamiherald.com/news/nation ... rylink=cpyhttps://www.miamiherald.com/