Moderators: Elvis, DrVolin, Jeff

Two new waves of deaths are about to break over the NHS, new analysis warns

Radical solutions will need to be found if the health service is to avoid formal rationing

Reorienting the NHS to focus on the Covid-19 emergency was essential but indirect deaths are mounting fast and now threaten to eclipse the carnage wreaked by the virus itself.

A new analysis by Edge Health, a leading provider of data to NHS trusts, warns that a second and then a third wave of “non-corona” deaths are about to hit Britain. Unless radical solutions can be found to resume normal service and slash waiting lists, the NHS may be forced to institute a formal regime of rationing.

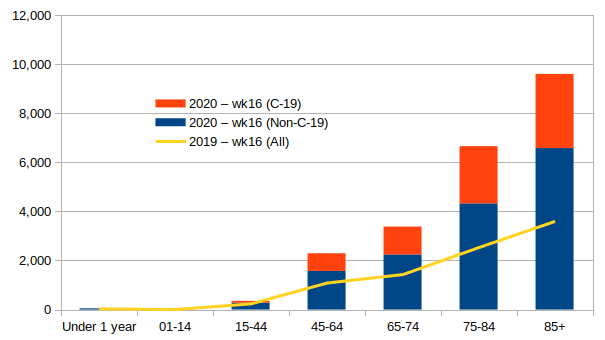

The “second wave” is already breaking. It is made up of non-coronavirus patients not able or willing to access healthcare because of the crisis. Based on ONS and NHS data, Edge Health estimates these deaths now total approximately 10,000 and are running at around 2,000 a week.

They include a wide range of typical emergency admissions, including stroke and heart attack patients, as well as those with long term chronic conditions such as diabetes who are not able to access the primary or secondary care services they need. Many are sadly dying in their homes. Others are just getting to hospital too late.

“If projected forwards, these numbers get so large it is hard to relate to them on a personal level”, said George Batchelor, a co-founder of Edge Health. “A guesstimate statistic that makes it more real for me is that in an average lifetime we each encounter around 20,000 people”.

This second wave of deaths is likely to roll on for as long as the NHS needs to be on a battlefooting with Covid-19 despite appeals by doctors for the sick to continue to access emergency services. Should the bottleneck stretch into the winter months, the monthly count of these indirect deaths can be expected to accelerate further.

There will then be a “third wave” of deaths for Britain to contend with. This is made up, not of emergency cases, but of people who are developing conditions such as cancer and heart disease which are going undiagnosed because of the Covid crisis.

These patients would normally have face-to-face access to a GP and then rapid referral to secondary care for diagnosis and treatment where needed. But this vital, life-saving process has all but ground to a halt.

Currently endoscopies, which are used to diagnose some forms of cancers, have been stopped entirely due to the risk of aerosolising Covid-19, for example. MRI scans have also fallen off a cliff.

“Unlike the current peaks, this third wave may be spread out over a longer period of time. But make no mistake this could be could be a very deadly wave”, says Mr Batchelor.

There are no easy answers for the NHS in tackling these pressures. The treasury mantra of “efficiency” meant the NHS, like much of British industry, was running lean ahead of the crisis with virtually no spare capacity or resilience.

Ministers point out that the NHS has not been “overwhelmed” by Covid-19 in the same way as hospitals in Northern Italy but this has been achieved at the expense of suspending tens of millions of regular check-ups, tests, operations and treatments.

As we reported yesterday, the dash to get patients out of hospital beds in the later half of March and early April was so intense that many frail and vulnerable patients were transferred into nursing homes - some of them carrying the coronavirus.

Mitigating the two waves of indirect deaths will hinge on how the NHS deals with the vast waiting list of patients that is mounting.

Over a month ago, trusts were told to assume that they would "postpone all non-urgent elective operations from 15th April at the latest, for a period of at least three months".

Already 2.1 million scheduled operations are thought to have been cancelled and this is on top of the 4.5 million people who were on hospital waiting lists before the crisis.

“Usually there are around 700,000 planned and elective operations per month. So over three months, that is a total of 2.1 million operations that will not take place,” said Mr Batchelor. “There might be some attrition to this demand, but it could also be higher as conditions worsen and need increases.

“We expect median waiting times will increase from 8.5 weeks to 13.5 weeks. This will be longer if urgent cases are prioritised.”

To clear this backlog, ministers will need to look to radical solutions, especially as Covid-19 is likely to remain, at best, a constant background drain on NHS resources until a treatment or vaccine can be found, manufactured and distributed.

Which epidemiologist do you believe?

The debate about lockdown is not a contest between good and evil

BY Freddie Sayers

The past week has been a tale of two epidemiologists. First up was Swedish professor Johan Giesecke, whose interview with UnHerd a week ago caused quite a stir. Disarmingly blunt, uninterested in percentage points, Giesecke brushed aside the coronavirus pandemic with words that electrified sceptics and horrified his detractors. “I don’t think you can stop it,” he said, “it’s like a tsunami sweeping across Europe.” The real death toll, he suggested, will be in the region of a severe influenza season — maybe double that at most — so we should do what we can to slow it so the health service can cope, but let it pass.

Then, this weekend, it was the turn of Professor Neil Ferguson to answer the Swede’s critique that his overly pessimistic forecasts had tilted the Government into Chinese-style dirigisme. He cut a very different figure — more cautious, more media-trained, lacking the charismatic heft of the Professor Emeritus but making up for it with precise deployment of the facts and figures. Much as he’d love to be proved wrong, he said, the UK fatality rate of Covid-19 is likely to be 0.8-0.9%, which means that even letting out only the young and healthy will lead to more than 100,000 deaths later this year. We need to prepare for a long fight, a new socially-distanced normal, potentially for years to come.

In theory, theirs is a purely scientific disagreement that boils down to Infection Fatality Ratios, seroprevalence assays, and R0 numbers — and one or other of them will eventually be proved right. But somehow I suspect there will always be enough controversy around how deaths are counted and the economic and health impacts of lockdown to defer that judgement indefinitely. It’s also quite possible that one of them could end up being right in spirit while wrong on the numbers.

Alongside all the metrics, and the vital assessments of the human cost of different policies, where you stand on this wretched virus also comes down to attitude — your world view. Are you more Giesecke or Ferguson? The expert that most resonates is unlikely to be entirely down to your assessment of the science — more likely a complex combination of your politics, your own life experience, your attitude to risk and mortality and your relationship to authority. Perhaps each of us have elements of both instinct within us — but what do they really represent?

What they are not, despite the attempts of some social media voices to make it so, are good and evil. Clearly, both experts are highly accomplished scientists doing their best to understand a complex threat. Likewise, the wider debate around lockdown is not a contest between rational, good people who value life on the one hand and the cavalier and cynical who care only about economics or themselves on the other. If the do-gooder class try to push that narrative, they will simply lose the argument.

There is not even an in-principle disagreement about the sacredness of every human life, despite attempts to slur those in favour of a speedier timetable out of lockdown as “pro-death”. The principle that some level of increase in infection, and therefore more deaths, is tolerable for the wider good is not often said publicly but is already accepted on both sides of the argument. Denmark, the poster-nation for early and stringent lockdown, has now brought back junior schools alongside published modelling that showed what level of increased infection (and therefore deaths) they expected it to lead to. Nobody raised an eyebrow, because the education of children is so obviously a moral good. It’s really a question of where you fall on a spectrum: how much death would you tolerate, for which wider goods?

In UK policy terms, the ‘landing zone’ now lies in the space between these two experts. At the Giesecke end, we would define success simply in terms of ensuring the NHS is not overwhelmed — this means slowing the spread and protecting vulnerable people as much as practically possible but moving to lift lockdown measures and only reintroducing them if the health service is challenged. At the Ferguson end, we would attempt to keep the outbreak at such low levels that we can wage a long-term ‘test, track and trace’ suppression of the virus, with elements of social distancing to minimise transmission until a vaccine is found.

The appeal of the first of these options is that it has a clear rationale and an end-point when the virus has passed and life can return to normal. But it suffers from seeming callous and is highly dependent on the quantum of deaths. If we have 100,000 additional Covid deaths within the year, as Professor Ferguson warned, but could get fully back to normal after that, would that be acceptable? At two people in every thousand, most people would then know somebody who died. What about only 20,000 more? Or 200,000?

The Ferguson end of things will likely be more attractive to politicians as, while sidestepping this difficult question, it carries with it a clearer sense of virtue and action. As Gov Cuomo of New York is now fond of saying, “we’re not going to accept the premise that human life is disposable.” There is a strong appeal to society pulling together to protect our most vulnerable, and we know from polls that the public continues to support the more cautious approach.

But it is dangerous because it has no clear measure of success, and no way out: if the goal is just to “keep transmission low”, how low is low enough? Any move away from total lockdown potentially takes you further from your goal, and back towards a relentless fear of cases starting to creep up once again.

Suggested reading

In the ‘Giesecke’ worldview, this would amount not to a victory but to a surrender. The world becomes a place of indefinite anxiety, with the constant threat of curtailment hovering over all that is best and most human in life — family get-togethers, religious worship, children playing, plans for the future, creative projects – it risks becoming a conscribed, smaller, more fearful world. At its most extreme, a long-term ‘suppression state’ really could start to feel like oppressive regimes of history, from the Puritans to the Communists, that misguidedly tried to remake the whole natural order in pursuit of a single definition of virtue. People who recoil from any move in this direction can hardly be dismissed, or called immoral.

Somewhere in between these two opposing instincts lies a wise way forward; a path has to be found between not just different assessments of the facts but different world views.

In between his careful words, I detected something of the idealist about Neil Ferguson — the younger of the two scientists was keen to break new ground and win a battle. “We’re in a horrible place, aren’t we,” I said, expecting him to agree, but he immediately countered that, on the contrary, the world has achieved what he never thought he would see in this century, and has collectively stopped a highly infectious respiratory virus in its tracks. The South Korean model offers hope for an unprecedented new technology-driven response to an epidemic. For an expert who has spent years looking at fatality rates and modelling outcomes this must feel like huge progress: the entire world united against a disease.

Meanwhile, somewhat ironically given the laser-targeted threat of this disease on the old and vulnerable, the Giesecke approach felt imbued with the more philosophical perspective of later life. He has seen many pandemics; we live in a world full of various threats and dangers, and we can’t stop everything to try to run from one new one. Young people must be allowed to do what young people do, and older people, without the luxury of unlimited years ahead of them, must be allowed to choose to go back to seeing their grandchildren and living a full life even knowing the risks.

Whether you’re more Giesecke or Ferguson, it’s time to stop pretending that our response to this threat is simply a scientific question, or even an easy moral choice between right and wrong. It’s a question of what sort of world we want to live in, and at what cost.

~ Prof Ferguson is a theoretical physicist by training. He calls himself a “mathematical biologist”, but as a professional biologist myself, I’d advise him to call himself a mathematician.

~ The article tells us "Clearly, both experts are highly accomplished scientists" It might seem so until we examine the track record of Ferguson with his mathematical models of real life events, which is actually on a par with that of Gypsy Rose Fakenitt in whose kiosk you can have you fortune told by...

~ You can’t compare Apples with Lemons: one is a medical doctor the other is a mathematician. Disease is not numbers; need to be understand in a broad view, that only doctors can provide.

alloneword » Sun Apr 26, 2020 9:24 pm wrote:23ABC (Bakersfield & Kern County, California) interview with a Dr. Dan Erickson and Dr Artin Massihi:

Deaths from Covid-19: Who are the forgotten victims?

[...]

The increase in mortality is not wholly explained by deaths attributed to Covid-19. Indeed, only between 51 and 60% of the excess in deaths can be explained by official Covid-19 reports. The data from New York state support these findings, with an even more striking picture in New York city. The two most likely explanations for the discrepancy between the overall excess of deaths and the extra deaths explained by Covid-19 are either there are additional deaths caused (or contributed to) by Covid-19, but not recognised as such, or that there is an increase in deaths from non-Covid-19 causes, potentially resulting from diminished routine diagnosis and treatment of other conditions. We believe that both are likely.

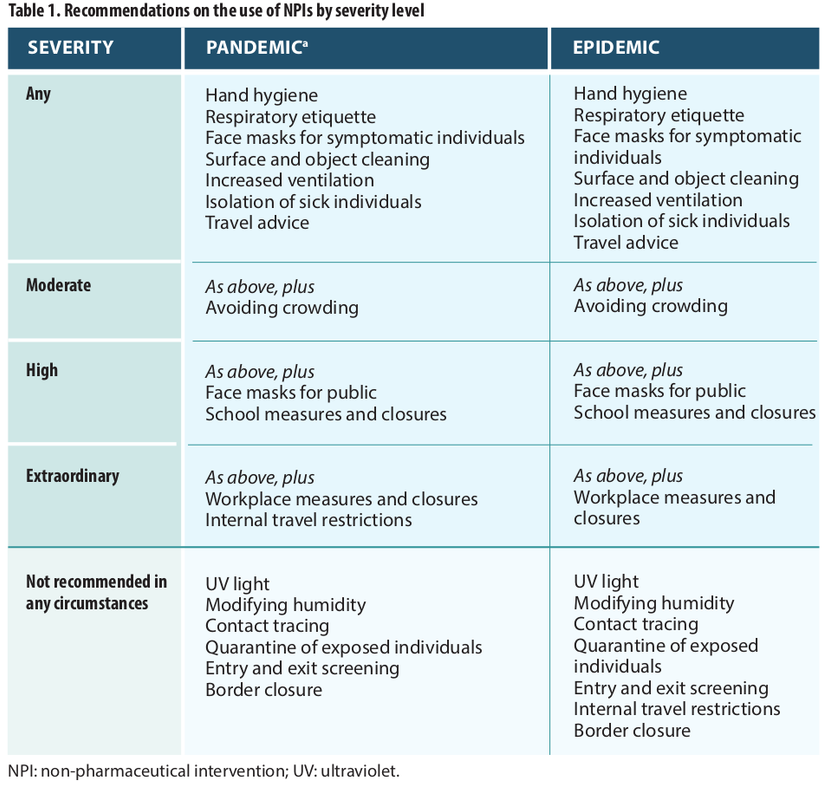

Table 1: Number of deaths where Influenza or Pneumonia is the underlying cause, by sex, Clinical Commissioning Groups in England, registered between 2015 to 2017

Table 3: Number of deaths where Influenza or Pneumonia is mentioned anywhere on the death certificate, by sex, Clinical Commissioning Groups in England, registered between 2015 to 2017

John Carmack

@ID_AA_Carmack

The Imperial College epidemic simulation code that I helped a little on is now public: https://github.com/mrc-ide/covid-sim

I am a strong proponent of public code for models that may influence policy, and while this is a "release" rather than a "live" depot, it is a Good Thing.

Before the GitHub team started working on the code it was a single 15k line C file that had been worked on for a decade, and some of the functions looked like they were machine translated from Fortran. There are some tropes about academic code that have grains of truth, but it turned out that it fared a lot better going through the gauntlet of code analysis tools I hit it with than a lot of more modern code. There is something to be said for straightforward C code. Bugs were found and fixed, but generally in paths that weren't enabled or hit.

Similarly, the performance scaling using OpenMP was already pretty good, and this was not the place for one of my dramatic system refactorings. Mostly, I was just a code janitor for a few weeks, but I was happy to be able to help a little.

[...]

That was my fear — what if the code turned out to be a horror show, making all the simulations questionable? I can’t vouch for the actual algorithms, but the software engineering seems fine.

Joffrey Thoms

@JoffreyThoms

·

17h

Replying to

@ID_AA_Carmack

A bit late for “May influence” donchta think?

..when asked if such a second wave was inevitable, Prof Pennington said: “No, I’m not sure where this ‘second peak’ idea comes from.

“Except, well, I know where it comes from, it comes from flu. Because when we have a flu pandemic we always get a second peak, and sometimes we get a third peak.

“Now, why we should get one with this virus, I don’t quite understand.

“It just seems to be a phenomenon with flu, and I don’t see any reason myself, and I haven’t seen any evidence to support the idea that there would be a second peak of the virus.”

Pandemic contingency plans had often focused on a deadly flu outbreak, and Prof Pennington believed that was fuelling fears of a second wave.

“It’s something that I think is a hangover from the flu pandemic planning,” he said.

“I think what we’ll get is, rather than a second peak, is the virus dribbling on, maybe there will be local instances where the virus will take off, and so on.

“We haven’t had a second wave in countries that have managed to control the virus, so why should we have one?

“I may be wrong, there may be a second wave, but I think it’s very unlikely that there will be a second wave.”

The claim: Hospitals get paid more if patients are listed as COVID-19, and on ventilators

Jensen said, "Hospital administrators might well want to see COVID-19 attached to a discharge summary or a death certificate. Why? Because if it's a straightforward, garden-variety pneumonia that a person is admitted to the hospital for – if they're Medicare – typically, the diagnosis-related group lump sum payment would be $5,000. But if it's COVID-19 pneumonia, then it's $13,000, and if that COVID-19 pneumonia patient ends up on a ventilator, it goes up to $39,000."

He noted that some states, including his home state of Minnesota, as well as California, list only laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 diagnoses. Others, specifically New York, list all presumed cases, which is allowed under guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as of mid-April and which will result in a larger payout.

Results: The first 9,496 blood donors were tested and a combined adjusted seroprevalence of 1.7% (CI: 0.9-2.3) was calculated. The seroprevalence differed across areas. Using available data on fatalities and population numbers a combined IFR in patients younger than 70 is estimated at 82 per 100,000 (CI: 59-154) infections.

The Emperor has no clothes: A sober analysis of the Government response to Covid-19

Posted by UK Administrative Justice Institute ⋅ April 28, 2020

Opinion piece by Eri Mountbatten-O’Malley (Edge Hill University)

The Government has been criticised for doing ‘too little, too late’. Proposals to suspend duties in the Care Act, 2014, have led Disability Rights to complain that there is ‘a real and present danger to the lives of Disabled people… effectively rolling back 30 years of progress for Disabled people’. Other regressive actions are taking place with citizens being tracked through their phones, fined for shopping for ‘inessential items’, and being watched by drones with even further restrictions promised if the public fail to adhere to Government stipulations. There is also an increasing concern about the rise of Police power with #PoliceState trending last week alongside #COVID1984. In some parts of the world citizens are being beaten with rods and in the Philippines there is live footage of President Rodrigo Duterte threatening citizens that he will order police to ‘shoot them dead’ if they fail to adhere to Government quarantine policy. Curfew is being enforced with tear gas in Kenya to disperse the crowds. The pattern is similar across the world.

The widespread perception of risk to life is of course driving public fears which has led to some of ‘the most momentous peace time restrictions on the liberty in peacetime, the Coronavirus Act 2020. Yet there appears to be widespread support for the quarantine measures. There is evidence in increases in social shaming as well and for example on twitter #COVIDIOTS is regularly trending. Some police forces are inundated with calls from diligent neighbourhood informants reminiscent of the breakdown of social fabric during long gone periods of autocratic European political history. The expansion of police and administrative powers is simply unprecedented and the social and economic fallout and ensuing human cost is unfathomable.

Although the Government must rightly do everything it can to protect the public, it must do so in ways that are proportionate to the risk. It must strike the right balance between respect for civil liberties and the legitimate aims for the protection of public health. Government justifications for the introduction of a wave of emergency powers however seems to have been predicated on misleading mortality statistics and poor methodological practices, contributing to what I term as a perfect sensationalist storm of error. This cannot be the basis for Government policy if we are to safeguard a healthy democracy.

A death, is a death, is a death… right?

The crude mortality rate in the UK (CMR) is the broadest measure of the total number of deaths from all causes in a given population, over a specific time period and is defined as total deaths per 1,000 population. Alternatively, the case fatality rate (CFR) is most often cited. Various subsets can be made using either age, gender or causal variables. In the context of an epidemic, the ‘case fatality rate’ (CFR) measures death rates in a population among diagnosed cases. This is important because CFR offers a picture of useful data for preparation of responsive services such as acute emergency care services. Importantly however, the infection fatality rate (IFR, also known as ‘true case fatality rate’, tCFR) is much more useful. This is because it helps to account for all cases of infection, including asymptomatic infections, in the wider population. The World Health Organisation (WHO) tends to publish its fatality estimates using CFR; however, as shown, this is method of measurement that targets those who seek emergency assistance and have been tested as a result of seeking emergency care. Thus, in countries where widespread testing is not instituted, such as the UK, CFR is misleading. This clearly amounts to a form of ‘selection bias’.

Unaccountable coding & risk projections

The two most influential studies in the UK to date, certainly in terms of Government policy, appear to be are Verity et all (2020), for China, and Ferguson et al (2020) from Imperial College. Verity et al use the broader CFR measure whereas Fergusson et all at Imperial College use IFR. However, Imperial use their own mathematical coding and modelling for estimating IFR. The trouble is that the ‘shocking’ Imperial College study released on 16th suggested that fatalities could be in the region of 500,000, in the UK and over 2,000,000 in the US. This study has almost single-handedly been responsible for the UK Government U-turn and a misleading characterisation of risk to public health. These figures have recently been revised down to around 20,000 of mitigated deaths. Understandably, experts keen to peer-review the coding have since raised a number of questions about the coding practices used to arrive at those figures. In response, Fergusson has tried to explain himself on twitter saying that he ‘wrote the code (thousands of lines of undocumented C) 13+ years ago to model flu pandemics’; this is far from satisfactory. Part of the problem is that the Imperial College model used projections from China and Italy to predict the rates of infection in the UK. Those are nations with significantly disparate social conditions to the UK. This was clearly a flawed standard to begin with.

Co-morbidities & post hoc fallacies

Relatedly, there is the issue of dubious death certification practices and new procedural guidance which seems to conflate COVID-19 deaths with other co-morbidities with a serious blurring of correlation and causation. There are a number of serious issues with both the revised methods of recording of COVID-19 deaths, as much as with the reporting of those fatalities. Both are having a misleading effect on the advertised numbers.

For example, guidance in the UK has recently been revised to account for COVID-19 as a notifiable disease. COVID-19 is now attributable as a ‘direct or underlying’ cause of death. However, in a note on the approach to mortality statistics, ONS stated that in publishing the figures, ‘it will not always be the main cause of death, but may be a contributory factor’ mentioned ‘somewhere on the death certificate’.

Further, Post hoc fallacies have been systematized as part of a wider certification policy-framework in numerous countries with revised reporting guidance in Italy, the US, UK and even Germany. Here in the UK, COVID-19 deaths are partly based on testing and the rather loose definition of a deceased person having ‘tested positive’ for the virus having then died irrespective of the actual cause of death. In an early report from the Italian National Institute of Health, one advisor to the Italian Government raised this as an issue there as well:

“The way in which we code deaths in our country is very generous in the sense that all the people who die in hospitals with the coronavirus are deemed to be dying of the coronavirus… On re-evaluation by the National Institute of Health, only 12 per cent of death certificates have shown a direct causality from coronavirus, while 88 per cent of patients who have died have at least one pre-morbidity – many had two or three,”

The other certification approach is based on symptoms. Guidance from NHS clarifies that if the test result has ‘not been received’ it would be satisfactory to give ‘COVID-19’ as the cause of death based on symptoms alone. However, we’ve also known for some time that COVID-19 is very similar to influenza so it’s unreliable to rely on presenting symptoms alone.

We therefore have a collection of errors from two extremes. On the one hand, the mere presence of COVID-19 through testing is enough to certify it as a cause of death (post hoc). On the other extreme, a clinical assessment based on symptoms is seen as sufficient ‘[w]ithout diagnostic proof’. The death certification and publication process is quite simply rife, layer upon layer, with confounding and misleading interpretation and representation of data.

COVID-19 in context

If we look at the Government published figures for COVID-19 as of 26th April the total is now 20,319. The seasonal flu deaths for a similar week period (using 5 year averages up to week 15) is 12,982. On the surface that seems like almost a doubling of fatalities, but once we factor that there is a two-week lag in flu statistics (only so far being published up to 10th April) compared with the figures for COVID-19 which are more or less live, we can estimate a further 4,000 in the flu back log. This would bring estimated flu deaths to at least 16,000 or more, not far off the published COVID-19 fatality figures. So, if we accept the published figures there is little difference between them over the first 15 week period of this year. In terms of overall deaths, these may well balance out with little or no excess deaths (excluding deaths indirectly related to the quarantine measures such as suicide). The BBC chart below helps to illustrate the anticipated risks overall a bit further as the pattern more or less tracks the same as if COVID-19 had not appeared:

Dr. William Schaffner, a vaccine expert at Vanderbilt University Medical Centre in Nashville, Tennessee (USA) has suggested that ‘When we think about the relative danger of this new coronavirus and influenza, there’s just no comparison… The risk is trivial’. It is suggested by at least one other a collaborative pre-review study out this week, including researchers from Stanford, suggests that the virus is likely ‘widespread’. Dr. Jay Bhattacharya, one of the researchers on that project, discussed the study in a recent interview where he suggests that the initial WHO forecast fatality rate of 1-3% was hugely out of step. Due to populational prevalence of COVID-19 (largely mild or asymptomatic), the actual fatality rates for COVID-19 is likely to be up to 10 times less severe than initially projected – closer to 0.1-0.3%. Even Fauci et all (2020) recently arrived at a similar conclusion:

“ …the overall clinical consequences of Covid-19 may ultimately be more akin to those of a severe seasonal influenza (which has a case fatality rate of approximately 0.1%) or a pandemic influenza”

In the coming weeks, all eyes will be on countries like Sweden who followed a policy comparable with the UK prior to the release of the Imperial College report on 16th March. So far, they have seen incomparably fewer deaths without any enforced quarantine. Indeed, some of the pre-review evidence from the notable Professor Wittkowski, former chief biostatistician and epidemiologist at Rockefeller University Hospital, suggests that our interventions may well have damaged our chances of reaching already herd immunity, increasing the likelihood of a second ‘rebound’. In the UK we likely peaked a week before the lockdown was even instituted, calling into question the whole efficacy of the policy. The list of dissidents against the status quo is growing day by day. Once we factor in the substantive issues raised here already, an honest assessment of the final fatality figures for COVID-19 deaths will likely be massively, not marginally, less fatal than flu.

The diminishing case for proportionality

Guidance from the WHO regulations (2005), specifically, Article 12 suggests that advice given to states should be based on ‘scientific principles’ regarding ‘assessment of the risk to human health’. As Benatar & Brock (2015: 93) aver, lockdowns should only be mandated ‘as a last resort’. Public health measures must be proportionate and should pay attention to the overall ‘net pay-off’ for mandated measures taking into account the potential harm on society. The maximal promotion of public health, no matter how conceived, should not become the ‘sole goal’ of an ethical public health policy. What this means is that for wide sweeping liberty-infringing measures to be ‘permissible’, the stakes need to be ‘very high’.

The problems I have raised here include the use of generalised CFRs infused with selection bias and flawed, unaccountable coding projections based on nations with considerably disparate socio-economic conditions. These issues have been compounded by government policies across the world which systematised post hoc fallacies. This is in defiance of well-established scientific, epidemiological and statistical best practice. Together these have contributed to creating a perfect sensationalist storm of error.

The Council of Europe advised that ‘the challenge for governments in this crisis is the ability to respond to this crisis effectively, whilst ensuring that the measures they take do not undermine our genuine long-term interest in safeguarding Europe’s founding values of democracy, rule of law and human rights’. Although, the quarantine measures seem to have met the ‘general interest of the community’ test early on, it is likely that this case is weaker by the day, particularly as the weight of evidence mounts and awareness increases against the prevalent (mis)conceptions of risk. We now have a reasonable understanding of this virus emerging from the crisis and we are slowly arriving at a consensus: that although particular groups are at risk, we are experiencing broadly similar levels of risk as standard influenza, with similar symptoms as well. I’d suggest that the stakes and the risk are therefore not at all high enough to warrant such sweeping Government measures. This is an issue that has also been recently raised by Francis Hoar QC who has undertaken a timely analysis of the relevant evidential grounds for lockdown and the ‘questionable’ scientific basis for lockdown. We need an honest assessment by the Government if we are to truly navigate out of this crisis.

The challenge for any government is to develop an approach to political decision-making that reflects an appropriate level of responsiveness to an emerging threat (apparent or actual), whilst also remaining sensitive to the need for proportionality under changing circumstances. This is a continual process. However, the UK Government response has been marked by a serious lack of transparency, regarding both the scientific basis for lockdown and the decision-making framework for easing of restrictions.

Decision-makers have the responsibility to respond to expert advice in the context of scientific best practice and legal principle with weighty (even paramount) consideration given for the very real needs and concerns of the populations they govern. If policy is based on scientific evidence, then as the evidence changes, we should see a change of both narrative and political decision-making. For some reason, this is not happening.

Final remarks

The consequences of prolonged lockdown are serious and I have absolutely no doubt that the human cost of these measures across the world will be so immense as to completely overshadow any perceived and debatable benefits of enforced lockdown. As Dr John Lee has suggested, ‘the moral debate is not lives vs money. It is lives vs lives’.

As a society, we must remain aware of the ever-present dangers and risks of being led by small groups of influential scientists. Laski once said, ‘we must ceaselessly remember that no body of experts is wise enough, or good enough to be charged with the destiny of mankind’. Scientific understanding is not the sole possession of a single individual or set of individuals; it is distributed, and its ‘locus is at the population level’. This ‘locus’ is a non-negotiable principle of any democracy worth its salt and we would do well to remember it.

If the evidence for risk to life is as problematic as it appears, it follows that the case for enforced quarantine and lockdown is increasingly hard to justify. If needlessly maintained, it could be noted as one of the greatest errors of political judgement and decision-making in modern history.

There is nothing virtuous in following a flawed narrative. It is deleterious to our national well-being and dangerous for the preservation of our British values, democratic norms and way of life. The question remains, who dares to doubt whether the emperor has any clothes?

Return to Data & Research Compilations

Users browsing this forum: No registered users and 6 guests